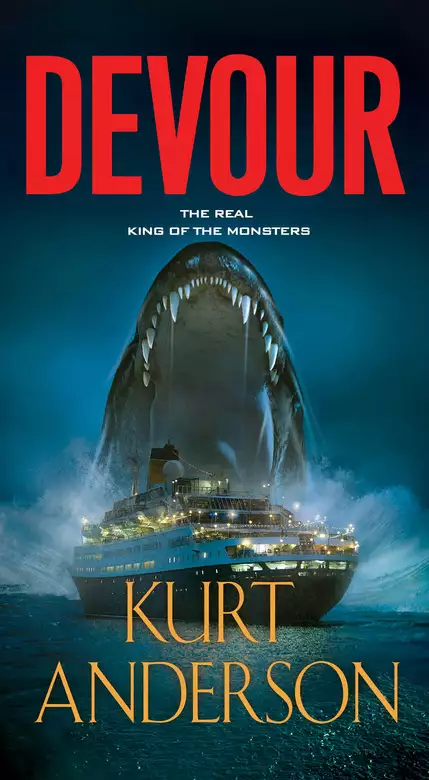

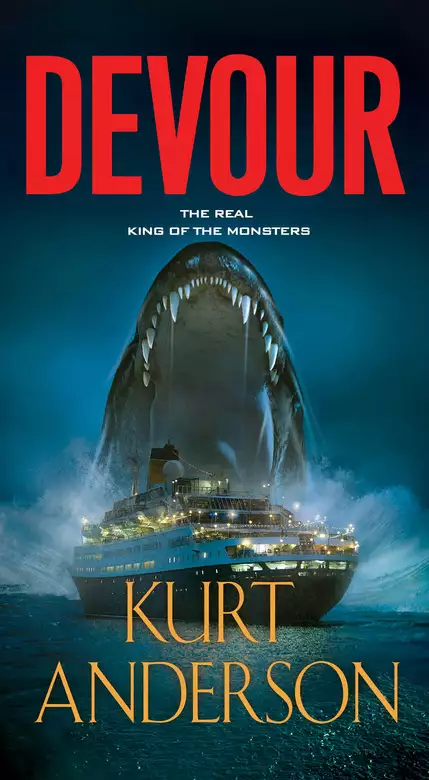

Devour

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A terrifying sea creature emerges from the deep to hunt for human prey in this debut monster thriller by the author of Resurrection Pass. Deep beneath the ice of the Arctic Circle, something has awakened. A primordial creature frozen in time, it is the oldest, largest, most efficient predator that nature has ever produced. And it is ravenously hungry… Thirty-five miles off the Massachusetts coast, a small research ship is attacked. All but one of its crew is killed by the massive serpentine horror that rises from the sea. Now the creature knows the taste of human prey. And it wants more… Responding to a distress signal, fishing-boat captain Brian Hawkins arrives in time to save the ship's last survivor. But the nightmare is just beginning. A casino cruise ship carrying high-stakes passengers--and a top-secret cargo--becomes the creature's next target. Desperate but determined, Hawkins goes after the biggest catch of the century. But there's something he didn't count on: There's more than one…

Release date: June 1, 2016

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 310

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Devour

Kurt Anderson

Something very large was suspended directly underneath the Tangled Blue.

Gilly Blanchard tapped the buttons on the Furuno sonar display, zooming in on the large half-moon arc just below their baits, which showed up as small fingernails on the sonar. The other two baits were positioned below bright orange floats, roughly thirty yards off each corner of the Grady-White’s stern. The floats were barely visible in the thick fog.

He turned back to the console, glancing at the readout from the FishHawk sensor, suspended on a lead ball weight twelve fathoms deep. The temperature at seventy feet down was only forty-three degrees, with a subsurface current of just over three knots. Overhead, hundreds of shearwater petrels swooped low over the water, their black-edged wings the only relief in an otherwise gray universe.

“You believe this, Cap?” Gilly called over his shoulder. “We got another looker.”

Brian Hawkins looked up from his chum board. He was cutting long strips of herring into chunks, using the side of the blade to carefully scrape away the long, bloody kidneys. Gilly liked to kid him about how careful he was with the bait, how fastidious he was in general, especially compared to how he could be the rest of the time. It didn’t bother Brian; he knew what he knew. Blood brought in sharks, and sharks were a pain in the ass. And this day, so far, had been remarkably free of pains in the ass.

“She gonna?” Brian said, chopping the rest of the herring fillet into three-inch chunks. He was careful in his speed, timing his cuts with the motion of the boat. Blades, waves, and fingers, he thought. Mix those three for any length of time, and eventually your gloves are going to have empty spaces in them.

“Dunno,” Gilly said. “Cruising for now. She’s a big one.”

Brian dropped a few more chunks overboard, then slid the rest of the chum into an ice cream bucket. He straightened, groaning at the pain in his lower back. He’d been meaning to build a little chumming station at chest level for years. He only seriously considered it after cutting bait, when his backbone felt like it had been pressed in a vise. By the time they got back to port, and the little workshop in the marina garage, his mind was nowhere close to bait cutting. It was set on that first drink—the best one of the day, as Hemingway used to say—or maybe just a warm bed.

“Getting old, Cap,” Gilly said.

“Experienced,” Brian said, rolling his shoulders. “Seasoned.”

He was forty-two, still able to put in a full day in the ship, and sometimes a full night in the bar. Maybe a little softer than he wanted to be around the middle, but hell. It was always that way at the beginning of the season, all those long winter nights in front of the tube, or parked in front of the bar at the Riff-Raff. The weight would come off, it always did. His short beard was still dark brown, with only a few rogue whites in the mix.

“You need a little pick-me-up?” Gilly asked.

Brian glanced at his first mate. When a man bought a boat, part of the process was negotiating over the gear included in the deal. Did the price include the outriggers? Fishing gear? Some men wanted to keep the existing electronics; others were only interested in buying the hull and would add their own equipment later. When Brian sat down with old Denny Blanchard that day in the back booth of the Riff-Raff, he had been prepared to haggle over all sorts of details, some he was prepared to give in to, others that were absolutes. He certainly sure hadn’t been expecting to get a first mate out of the deal, especially one with three DWIs, two stints in county for distribution of a controlled substance, and a gimpy leg from rolling his daddy’s diesel truck on I-95 at three in the morning.

“Prescriptions,” Brian said. “For every damn pill you have on board.” He motioned out to the gray wall of fog that encircled the boat. “I mean it, Gil. The Coast Guard comes up on us in this crap and—”

Gilly held a hand up. “First,” he said. “I’m keepin’ eyes on the radar, dude. I’m not blind. Ain’t no pings within ten miles.”

“Dude?” Brian said. “Denny’d roll over in his grave hearing you talk like that. You’re forty-seven, not seventeen.”

“Then I’m sure he’s twisted up like a mummy by now,” Gilly said. “If he cares enough to pay attention to me when he’s dead. He sure didn’t when he was still kicking.” Gilly grinned. “Second, you know the lamedick Coasties are scattered all over hell and gone. There’s been what, three sinkings up by Fundy, another down by—”

He was interrupted by the sound of the rod banging off the port side, followed by the scream of the drag on the big Penn reel. Brian slipped on his gloves and moved quickly to the corner rod, a nine-foot Fin-Nor, bent over nearly double. The 200-pound test monofilament was flying off the reel, the line counter flashing past a hundred, a hundred fifty, then over two hundred in the span of seconds.

“Big one,” Brian said, wrapping his hands carefully around the rod handle. He needed to wait until the run was over before removing the rod from the rod holder. On smaller fish that wasn’t always the case, but today the fish were running large. Running huge, actually. They didn’t use stand-up gear on the Tangled Blue, and if one of these behemoths yanked the rod out of his grip Brian would be out close to two grand. It was better than being strapped to the bastard when it went over, but it still wasn’t good. A different kind of hurt.

Gilly limped to the other corner of the boat, flipped the reel on the other rig to high gear ratio, and started cranking in line. He got the float in, unsnapped it, and rolled it toward the bow. By the time the float bounced down the stairs and into the cuddy he had the line out of the water, the live herring wiggling in the air with the big 11-ought hook through its nose. Gilly flipped the herring off the hook and stowed the rod, then moved on to the other two lines. Brian barely noticed. The first mate of the Tangled Blue had his faults, as did her captain. But there wasn’t a man in Gloucester who could clear a deck as fast as Gilly Blanchard.

Two minutes later the gear was stowed and Gilly fired up the twin 350s, then activated the automatic retrieve on the windlass anchor. The fish had pulled out four hundred feet of line and was cutting hard to the port side, still pulling drag at a relentless pace. Brian shook his head and took a deep breath, waiting for the brief lull when he could pop the rod free.

A good day on the water was one fish. Two-fish days happened rarely. Three-fish days—a one-man limit—were epic, the kind of day where you almost cringed, thinking of the hangover that would result from that night’s celebration. Many boats never raised three fish in a day, and more than half never saw two in the hold in a season.

The pitch of the drag changed, and the tip of the Fin-Nor rod came up a fraction of a degree. Brian slid the rod out of the holder and pulled back steadily. This would be their sixth hookup, perhaps their fifth fish of the day. And all of their fish had been caught off a little underwater hump at the edge of this icy, food-rich current streaming down from the north.

“Take it ten degrees starboard,” he called out over his shoulder. The big 350s rumbled under his feet as Gilly positioned the boat so the line was straight out the back. Brian watched the spool grow steadily smaller. He was down to the backing now, braided Dacron line that made a slight sizzling sound as it coursed through the roller guides.

“Out four thirty,” Brian said, just loud enough to hear over the rumble of the engines. “Five hundred, five twenty-five.” He shook his head as the numbers on the counter whirred past. “She’s out six and still going strong.”

Gilly whistled, lit a cigarette. Six-fifty was the magic number.

“We chasing?” Gilly hollered.

The line counter went past six hundred and fifty feet, with no signs of slowing. “We’re chasing,” Brian yelled, and despite the sore muscles in his shoulders and back, despite the black thoughts that had once again begun to circle his mind, he offered up a tight-lipped smile to the foggy world, to the shearwaters who chirred and darted above them. Nothing in the world could compare to the thrill of hooking into something stronger than yourself and trying to make it your own.

It came up slowly, the rod quivering slightly from Brian’s aching shoulders. He’d been fighting for a little over two hours, gaining a few inches here, a foot there. They were a half mile from the original hookup, and he had only started to gain serious amounts of line in the past ten minutes. The tendons in his left hand, which he used to pull in line while reeling with his right, were ready to cramp.

Gilly moved up next to him, held up a plastic water bottle to his mouth. Brian drank quickly, eyes trained on the line stretched tight in front of him. The fish was starting to cut to the side, and angling up and out. Moving slowly but surely, like the good ones inevitably did. The other fish they had caught that day were large—giants, by definition—but none of them were in this league. An epic fish for an epic day.

“She’s coming in,” Gilly said. “We’re gonna be weighted down something fierce, we land this sow.”

Bad luck, Brian thought. Never talk about size until you wrap the damn rope around its tail. “Stick ready?”

Gilly lifted the harpoon, checked the coil of rope. “She’s ready. How long, you think?”

“Not long,” he said. “But she’ll have a hell of a boat run.”

“Nope,” Gilly said. “She’ll turn on her side, I’ll stick her, and then you and I ain’t gonna see this side of sober for a week.”

Brian had to grin. He hadn’t been on a legitimate bender for a while, and partying with Gilly usually left him half-paralyzed and wondering about liver transplants. But if they did land this fish, a good old-fashioned drunk was obligatory. Even without it, they had close to thirty thousand dollars of catch in the hold. If the meat was especially fatty, they might get another ten or twenty percent. Add in this one, and—

The rod went suddenly limp in his hand and he reeled in furiously, flipping to high gear retrieve with the pad of his thumb. It was gone, the fish of his lifetime was gone because he had let himself get distracted, had let the goddamn thought of money enter into the equation of man and fish—

Tension surged back into the line, and the drag screamed again. Brian watched as the fish stripped another hundred feet off the reel, reversing the past twenty minutes’ worth of work. The fish had simply made a run toward the boat, something he hadn’t expected at this point in the battle. He switched the gear ratio back to low, checked the drag. “She’s a funny one,” he said to Gilly, who had moved back to the wheel to reposition them. “Flipped direction like a skipjack.”

“Something down there,” Gilly said, tapping on the sonar screen. “Must’ve spooked it.”

“Shark?”

“Nah, looks like a humpie or a blue. Weird hook for a whale, but that’s all it can be. Gone now.” He tapped the menu button, switching to a wider transducer angle, and pointed at a large orange arc at the very edge of the screen. “There it is, leaving the scene. Fuckin’ blubberhead.”

The last run seemed to have exhausted the fish. It came in steadily after the last surge. The braided line came back up the guides, and the mono began to fill the spool. Gilly picked up the harpoon and stood to Brian’s left, looking over the side.

“Oh my Jesus Christ,” Gilly said. “It’s a half-tonner.”

The giant bluefin tuna came in slowly, an indigo-and-silver behemoth. It was hooked well in the corner of the mouth, the barb of the big hook clearly visible below its softball-sized eyeball. Its rear dorsal and anterior fins curved back like scimitars, the large dark tail moving slowly through the water.

Easily a half-tonner, Brian thought, temporarily forgetting his own jinxes on guessing weights before the fish was in the boat. Hell, it might beat Fraser’s record. He had been fishing for a living for six years, and catching fish regularly for the last four. He had never seen, nor heard of, a bluefin nearly this large.

“You miss this goddamn thing—”

“I miss that fish,” Gilly said, hefting the harpoon, “you take me to the charity house for the blind and retarded. It’s as big as a goddamn house.”

The bluefin, only twenty yards from the boat, started to turn sideways. It was a long throw for even a good stick man, but Gilly was right—it would be hard to miss. Gilly brought the harpoon to his shoulder, and as he did the tuna seemed to see him, or sense his intentions. It turned away and swam hard down to the depths, pulling more drag off the reel, but slowed after only about seventy feet. Brian carefully applied pressure to turn it around.

He cranked down slowly, steadily. The hook had been in the fish for two hours now, long enough to wear a hole in the fish’s mouth. Every turn, every run enlarged that hole, and made it easier for the hook to pull out. A fish like this was not only epic, it had the potential to be worth six figures—or more. A recent bluefin tuna of exceptional quality had just sold to a Japanese fish broker for $1.7 million. For a guy eighty grand in debt, they were numbers hard to put of mind.

“Hit it as soon as you can,” Brian said. “Stick her hard.”

“Yeah, Cap,” Gilly said. “I got her.” He was serious for once, Brian saw, even a bit nervous. Probably thinking of all the tail and blow he could score with his first mate’s share of today’s catch.

The tuna made another short, hard run just out of sight of the boat. The rod bounced hard twice, three times, then stopped, became deadweight. Brian pulled back on the tip slowly, feeling the fish out—was it dogging him, swimming away just hard enough to create a stalemate? It didn’t feel like it was even moving. The weight on the other end was solid, unmovable.

“What’s she doing?” Gilly said.

The line started to peel out again. It went slowly at first, then faster, stripping hard-won monofilament back out to sea. The number on the counter, which had been as low as fifty-two, slipped past a hundred. A hundred and fifty. Brian leaned back on the rod a bit, made a small adjustment to the drag.

“Don’t break,” he whispered. “Don’t you break on me now.”

The line picked up speed, hit three hundred. Gilly set the harpoon down and slowly backed to the wheelhouse. Brian looked back at him and nodded, and Gilly put the transmission in reverse. The big props churned, moving them backwards at two knots. Yet still the line stripped out, with no signs of slowing.

“Give it more!”

Gilly pushed down on the throttle and the Tangled Blue plowed stern-first into the four-foot waves, seawater splashing up and over Brian. The spool spun faster and faster, now well into the Dacron backing again. It didn’t make any sense. He’d seen the fish, and large as it was he could have sworn he’d broken it. But he had never hooked anything this large, either. He held the rod tip high and reared back, trying to turn the massive fish one more time.

And still the line went out, the spool now half-gone.

At twelve hundred feet Brian yelled for Gilly to turn the boat. They should have spun at a thousand, but he had been so sure, so goddamn certain, that he could turn it.

Gilly turned the Grady-White in a tight circle, costing Brian another hundred and fifty feet on the one-eighty. By the time they were pointed at the fish, he could see metal on the inside of the Penn’s spool. In a few more seconds it was over. There was a sharp snap as the backing popped off the spool, and then the line disappeared through the roller guides and into the sea.

Brian staggered back at the sudden loss of resistance, almost losing his footing on the wet floor of the boat. Gilly set him down on one of the yacht chairs, his eyes watching the seas to see if the massive fish might float to the surface, its heart burst after the long battle. But the seas were empty, even the shearwaters gone.

They looked at each other for a long moment, the exhaust from the engines wafting over them. Brian could not feel any distinct sensation in his arms except the sharp ache from his tendons. All else was a throbbing, burning pressure. He wondered if he was having a heart attack.

“Big fish,” Gilly said.

“Yeah,” Brian said. “Woulda been a keeper.”

Gilly turned back to the wheel. He put the transmission in forward, and after a moment the deck cleared of exhaust fumes. They continued on in silence, moving at a slow troll through the fog-laden chop back to their original mooring. Sometimes at sea there was nothing to talk about. And sometimes, there was so much to talk about that a man couldn’t say anything at all.

The call came in over the radio twenty-five minutes later.

“Mayday-Mayday-Mayday. This is the research vessel Archos. Mayday-Mayday-Mayday.”

Gilly reached down and turned up the volume on the marine radio, then picked up the handheld transmitter. They had just finished stowing their gear and were having a rare onboard beer together when the marine radio started talking.

“Mayday-Mayday,” the voice said again, the panic obvious through the crackle. “We are a research vessel operating two miles off of Boon Island. We’ve struck an underwater object and are taking on water. The bilges cannot keep up, repeat, the bilges cannot keep up. We are going down fast. Mayday-Mayday-Mayday.”

They looked at each other. If the Coast Guard picked up, the Tangled Blue would wait for guidance, perhaps even offer assistance. But the amount of static on the transmission suggested the Archos had an undersized marine radio antenna, a common and deadly sin on the open ocean. The Tangled Blue had a thirty-foot marine antenna, good enough to transmit for fifty miles or more under the right conditions. After a moment, Brian reached over and took the handheld mike from Gilly’s hand.

He clicked on the transmit key. “Archos, this is the fishing boat Tangled Blue. What are your numbers, over?”

There was a burst of static, and then the man’s voice came on again, the panic now mixed with excitement. “Thank God,” he said, his voice booming and distorted. “We don’t know what happened, we were just anchored and all of a sudden—”

“Sir, you need to settle down, and hold the mike farther away from your mouth. Give me your numbers, your GPS coordinates. Over.”

“Right . . . Sarah! What are our coordinates?”

The man repeated them, and Gilly reached under the dash and scribbled down the numbers.

“Good,” Brian said. “Now repeat the coordinates. Over.”

“We’re going down, for Christ’s sake!”

“Repeat the numbers,” Brian said. “Over.”

The man swore, shouted at Sarah again, and spit the numbers out. Brian understood the man’s frustration; he also knew more than one rescue attempt had been unsuccessful because of an incorrect latitude or longitude reading. Gilly wrote the repeated coordinates underneath the original numbers:

Gilly ran his index finger across the numbers to cross-check, and then punched the coordinates into the Furuno, which doubled as a chartplotter. The Archos appeared as a small blip on the screen, sixteen long miles away.

“We have a fix on your position,” Brian said. “Hold for a second, over.”

He handed the microphone back to Gilly and pointed at the numbers. “See if we can skip those to the Coast Guard.”

Gilly repeated the distress call to the Coast Guard while Brian did the math in his head. Top speed was about twenty-seven knots in these seas if the Tangled Blue was unloaded, with their current half-full fuel tank. With well over a ton of ice and giant bluefin tuna in the hold, they would do no better than sixteen or seventeen knots, tops. It was the difference of a half hour to get there unloaded, versus an hour loaded.

Brian turned to Gilly. “Tell me good news.”

Gilly shook his head, “Still up in Fundy, looking for floaters from the Margaret Jane.” The Jane was one of the three ships that had gone down in the Bay of Fundy in the past week. “They’re out ninety minutes, two hours. No chance of air assistance with this damn fog. Can’t raise anybody on Boon, either.”

Brian rubbed his forehead, then held out his hand for the mike. “Archos, Archos, Archos, this is Tangled Blue. Do you copy, over?”

“We’re here, Tangled Blue. Did the Coast Guard answer you?” The Archos could hear the transmissions from the Tangled Blue, but not any responses.

“We’re coming to your assistance, Archos. But we need to know your exact situation. Do you understand, over?”

“We understand, over.”

“How much water is in the boat? How long will you stay afloat, over?”

There was shouting from the other side, at least three or four different voices. All of them filled with panic. “It won’t be long,” the man said. “Ten minutes, maybe fifteen. We don’t have a lifeboat.”

“Do you have life jackets, over?”

There was a pause. “We do,” the man responded slowly. “But the water is very cold, Tangled Blue. We won’t last long.”

“Hold on as best you can,” Brian said. “We’re on our way.”

He tossed the microphone on the dash and walked back to the hold. He leaned down and popped the lid, uncovering four massive bluefin tuna, the first of the year for any boat in the region, the thick bodies covered in the ice from their onboard machine. That ice allowed them to achieve the top market price, well worth the extra costs for the machine and lower fuel mileage the weight of the ice caused. Each tuna was worth thousands of dollars, just one of them enough to cover his operating costs for most of the season. He reached over and pulled a stainless-steel hook from the gunnels.

He looked up at Gilly. “Come on, give me a hand.”

Gilly stood, spit over the side of the boat. “They better be worth it.”

Brian sunk the tip of the hook deep into the rich, red meat of the nearest bluefin. “They won’t be.”

Captain Donald Moore stood on the deck of the Nokomis, watching passengers stream along the boarding dock, forty feet below him. It was a calm, gray day with a light west wind. He held the fax from his first mate in one liver-spotted hand, the paper fluttering in the light offshore breeze.

The passengers moved steadily on the boardwalk below him, mostly middle-aged couples, some younger people, even a few children. Some of the passengers carried their own luggage; others walked with bellmen pushing their carts behind them. Moore watched with interest. He liked to see the people he was going to spend the next week with, not the individuals but the general type. Sometimes you could tell they were all going to be assholes; sometimes it was just the vast majority. Now he saw the low ratio of people carrying their own bags and figured it was going to be a typical voyage, heavy on the assholes.

The complaints would be endless. The sea is too wavy. It’s too cold. Too hot. Captain, there’s a lady on C-deck who is suffering from motion sickness and wants to return to port.

Moore leaned against the railing, the cool rounded brass pressing against his belly. Sheep, he thought. They go into a floating hunk of metal, head into one of the deadliest oceans in the world, then complain when it’s bumpy.

Well, maybe this would be different than the cruise ships, where all anybody wanted to do on those trips was relax, get drunk, get laid. Plenty of time to bitch about what was wrong in the downtime. This was different, all the bells and whistles of the slot machines, the cards spinning out onto the felt, the chips coming and going. Maybe it would be different, maybe not.

He glanced back at the wheelhouse, at the Zeiss binoculars that had been a present from his first wife, Chanterelle, twenty-nine years ago. The glass was still unscratched, the optics superb. Sometimes, when he put the binoculars up to his eyes, he thought he caught a trace of the light perfume Chant used to wear.

Moore considered getting the binoculars, then dismissed it. He didn’t need to look down there and see their faces. And he didn’t need the ewes to look up—as they always seemed to do just before boarding—and see their captain peering down on them with binoculars. Some dirty old man in a clean white uniform.

Below him, a couple was arguing about something, probably the weight of the woman’s luggage. He thought back to his inaugural captain gig, standing on the deck of the cruise ship Santa Barbara, watching and listening to a short, well-groomed passenger hurling abuses at one of the baggage carriers on the boardwalk below them. Moore had been nervous, excited about the imminent voyage, the gravity of their charge. He had been a bit dismayed at the passenger’s lack of couth, and said as much to his first mate.

Know what’s the difference between a cruise ship and a cucumber, Captain? the first mate said.

What? Moore’s voice was sharp. He was nervous, and when he was nervous he was snippy. He also felt the distinct urge to have a stiff drink.

On a cucumber, his first mate had said, all the little pricks are on the outside.

Now, aboard the 272-foot-long Nokomis, he heard footsteps along the gangway, followed by an exchange between Collins, his first mate, and another baritone voice. A wiry, dark-haired man of medium height emerged from the doorway, somewhat stoop-shouldered, chest hair pushing out of the unbuttoned collar of his white oxford shirt. Moore thought he looked like the kind of man who should be wearing a gold chain, tattoos on his forearms.

Another little prick.

The man looked at Moore, glanced back down the narrow aisle to his right, then strode over, hand outthrust. “Captain Moore? It’s been a while.”

Moore took his hand, paused, and readjusted his grip. He had forgotten; Rollins was missing two fingers on his right hand. “Nice to see you again, Mr. Rollins.”

Rollins nodded. “Frank, Captain Moore. Or Frankie, like my friends call me. I don’t mind.” He reached into his jacket pocket, and Moore took a cautious half-step back.

Frankie withdrew his iPhone, pretending not to notice Moore’s recoil. He tapped the screen a few times, then peered down at the readout with the annoyed squint of a man who needed bifocals. He held the screen out for Moore. “We’re in for some weather.”

Moore glanced at the screen politely, then opened the fax Collins had handed him earlier. He let out a long, measured breath. Despite the cal. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...