PROLOGUE

It is a long way, as the heron flies, between lights in this part of the countryside. There is much silence and gloom in between, though the air is never completely still. Things rustle and murmur; creatures slink and scurry. Not just animals, but the occasional human too. The expanse is too forgiving for those with malign intent, and you can disappear into the twilit softness with great, alarming ease.

A woman stands atop old and crumbling stairs. There is pain in her eyes, but not fear, not quite yet. In a few moments, she will be crumpled on the ground below; the drama and striving, the passion and the pain of her life over. She has been watched all evening. In fact, she has often struggled to evade attention over the last few years, to find peace even in the wideness around her.

It is hard to separate some of the nearby men from the land itself. They work it – as she does – and it sticks to them, the smell of soil and growth and decay. She is surrounded; they are camouflaged. She strokes the downy hair on her arms, as a few goosebumps pimple her skin. The breeze is rising, she feels high in the sky.

She wonders if he is nearby, crouched furtive deep in a shadowy recess, watching and plotting. It is, sometimes, unbearable to imagine it. Her life here has been hard; she is an outsider, an invasive species. And yet she has found moments of solace in the thick land and silvery waters, in the sights and sounds of a natural world completely heedless of her needful fears. She has even found companionship with people on occasion. A friendly smile, an evening of carefree conversation.

But also constraint and fear. Dark, glowering eyes following her home, the physical threat of a man’s unforgiving bulk. Not just one man, but several. A group, a gathering; a rape of men like a murder of crows. She had coped, and struggled, and made herself small, got herself lost in the open spaces. And then the blow had fallen, the cataclysm, the catastrophe.

Elsewhere, a man sits in his home. He doesn’t love technology, but has become more adept with his camera over time: he used to have a darkroom, the sickly sweet toxicity of chemicals filling his nostrils and stinging his eyes, as the objects of his attention loomed back into ghostly existence. Now he is downloading images onto a computer, the screen-light dancing on a face that has been creased and hardened by the elements. He wonders if the people close to him know what is in his mind all of the time, the relentless throbbing of his senses, the things he is thinking when he stares at them. Of course they don’t know, otherwise they would have stopped him. He looks out of his window to check he is not being seen.

Somewhere else, two men meet by an old tree. Their cars are parked apart on the lane nearby, facing in opposite directions. The exchange is brief: two bags change hands, one of cash, one of product. They barely speak. They know that silence and security is essential. They cannot leave loose ends.

Lights flicker on in far apart houses. If you could swoop, quiet as a bat, and peer in through windows you would see family life in all its forms. The laughter between mother and daughter as bedtime approaches. The awkward stiffness between husband and wife who have run out of things to say to each other, and sit restless and aloof. The widow lost in front of a television screen. Two grown-up brothers who should have left home in pursuit of separate lives, but have been imprisoned by their own lack of ambition, their vitality and empathy drained year after year. One sneaks out while the other dozes in the corner, his dirty boots falling off his feet, the night outside preferable to these four walls. An old man at his kitchen in a dirty long shirt, painting the woman now standing on the tower. He can see her in the daylight of his imagination, the reflection of the water playing idly upon her pale skin.

The moon outside has glibly appeared, cold and sterile in the darkening blue of the dusky evening. As meaningful as a child’s drawing, indifferent as everything else.

Beginnings

A country road. A tree. Evening. The taxi from the station, a wheezing old Toyota the same pale blue colour as the sky, had reversed into a gap in the hedge then chuntered away, exhaust rattling. He pauses to let the noise fade; he is hungry for silence. He has spent years – all of his adult life, in fact – in a big city, where it is never dark, never quiet, and he suddenly feels tired of the very idea of noise and brightness. The last hum of the car disappears, and he exhales slowly. There is not quite nothing left in his ears: the sigh of the wind rustles the leaves of what he supposes is an oak tree, the one visible landmark in the area. Two birds chirrup. But this is definitely a start.

All around him stand empty fields, thick and green, freckled with daisies and thistles and dandelions, unkempt like he always is. In his hand is the crumpled bit of paper that has the instruction: ‘Get the taxi to drop you off at the oak tree; that’s as close as you can get to the house.’ It had not been easy convincing Josef, the driver, to agree to make a journey to a tree, but he had acceded with something approaching good grace. Family was important to Josef – he had pictures of a wife and daughter taped to the dashboard – and he clearly liked the idea of honouring an uncle’s wishes. Jake had tried to keep his explanations to a minimum, not least because he is not sure himself why he has come here, his whole life so easily enclosed in a gym bag and a scarred black suitcase. In the back of the car, he had noticed, hanging forlornly on the suitcase handle, the airline tag from their last holiday, on their third recovery period. They had gone to Ibiza for some sun, had sat by a pool while he slowly, unwillingly burned, not talking much. He had started pale and milky, she always seemed effortlessly tanned. They drank a lot in the evenings, but stopped before their inhibitions made them say something they might regret. That poolside had a different type of quiet; the unhealthy, stilted, silted-up kind. The quiet of two people thinking busily, but unable to communicate. The silent dead thing between them again.

Jake breathes out once more, and picks up his bags and heads to the gap where the car had reversed. There is the faint outline of a track ahead of him, stretching out over the hump of the land. It is nearly six, so plenty of a summer’s evening left; that most pleasant part of any warm day, the sun a faded glare behind him, beginning its descent towards the other horizon. Before he continues walking, he awkwardly shuffles both bags into one hand and pulls out his phone. No signal, no internet. He had been warned this would happen in the letter. In the last ten years, he can count the number of times he has been disconnected from technology, mainly when he was on a plane. He remembers how he and Faye used to message each other all the time. Little love notes, jokes, miniature revels in the banal. That was one definition of love, he had thought: taking pleasure in sharing the boring bits of life. What you’d had for lunch, something you’d heard on the radio, what the neighbour had said when he slipped on the steps. And that was one definition of love ending: when the boring stayed boring, when there was no point in talking any more.

Jake’s hands tingle after a few minutes tramping up the incline. He is unused to this physical burden. As he reaches the modest peak, he peers downwards into a valley of more fields, a patchwork of green, mustard yellow and a deep brown. The breeze is stronger for a moment, and cools the sweat on his brow, bringing with it a pleasant earthy scent. There is life in the land, in the air around him. He cannot see his destination yet, but that is not surprising. The letter instructed him to find the path at the bottom of the pasture, and march east along it for a mile (there was a sarcastic parenthesis telling him that ‘east’ means left as he faces away from the main road).

It amused him that a man’s last wishes could convey sarcasm, an eyebrow raised from beyond the grave. Uncle Arthur had never been a prominent presence in his life, but always a memorable one: visiting erratically in Jake’s childhood, staying for a few days when he did come, the dining room converted into his living quarters, a mattress on the floor, clothes piled in the corner, the whole place filled with the exotic smell of cigars, the tortured sound of jazz trumpets coming from his portable stereo.

Arthur lived the rest of the year in America – Florida, the state of Disneyland and the ever-elderly, in Jake’s imagination – and sent ironic postcards when the mood took him, and came and went with mysterious abruptness. In Jake’s teen years, his awkward, gangly, frustrated period, when his innards roiled with speechless frustration and angsty lust, Arthur was always a soothing presence. ‘You don’t need to talk about anything,’ he would say, ‘just sit down and read this.’ He always carried a pile of books in his luggage, and left them with Jake when he departed: some big thick Victorian novels, some American new releases, classics and rarities. And lots of detective fiction, from all over the world. Jake once wrote to Arthur that he had started him on the road to the police force, and hoped it gave the old man satisfaction.

After Jake’s parents’ funeral, Arthur had visited only once. He had suddenly aged, Jake thought, his Florida tan scored with thick wrinkles like plough lines, his spryness stiffening into something more pitiable.

‘I have got to the point in the world,’ he confided one evening, as they sat outside Jake’s student house, Arthur perching on a wheelbarrow with his cigar in one hand, Jake balancing on the only piece of garden furniture they possessed, ‘when I can’t really face things any more. It’s all getting too much for me. I want to find some peace somewhere.’ This struck a far more sombre note than Jake was accustomed to, even given the sombre circumstance of his own sudden orphaning. Arthur had loved life as much as he had loved literature. He had never married, but Jake always suspected the presence of romantic relationships somewhere, always felt that Arthur’s pursuit of pleasure had taken him into other people’s existences. That last time, Arthur had stayed for a few days in the house, and then performed his usual sudden departure. His remaining contact with Jake had come in the form of letters at indiscriminate intervals, some short and gnomic, others long and indulgent, reflecting on his own childhood and relationship with his brother, but never about his present circumstance. Jake always responded, to a postbox somewhere in one of those anonymous rural counties in the middle of England, and had always felt reassured of his uncle’s interest.

The path meanders east, and Jake pauses again for breath, and to rest his aching arms. In the last half hour, evening has truly come, the shadows are long, the air settling into the cool of the night, the breeze dropping down to a decorous whisper.

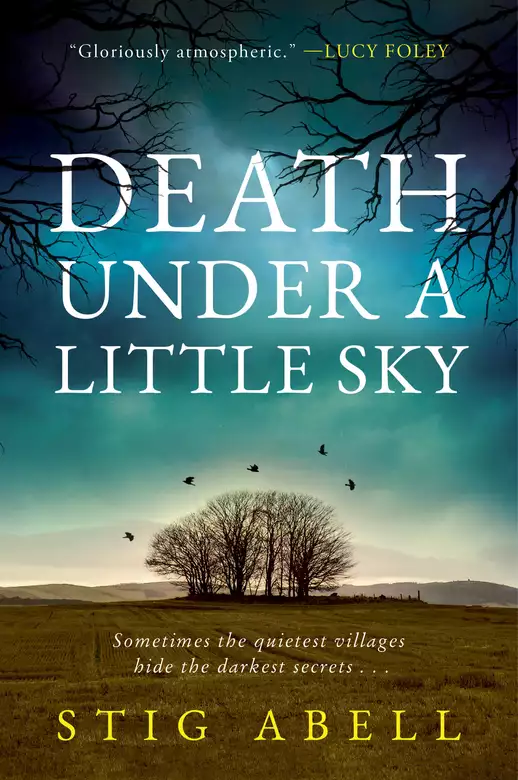

He knows he cannot linger; there is so much he will have to do when he arrives. After twenty more minutes huffing along the path, he sees it ending abruptly at an old wooden stile, mottled with moisture and close to toppling, its base skirted with long grass. A small sign has been nailed alongside it. WELCOME TO LITTLE SKY, it says.

Home

Jake throws his bag over the stile and stands on it, to look down into what is now his property. He has been noticeably climbing again over the last few minutes, and has clearly reached the high point of the area. Beneath him now is a steep path through yet another field, descending into a valley. To the left there is a dark smear of purple-green, which looks like a wood, and further beyond something shimmers rose-gold in the final sunlight of the day. Some sort of body of water, like a lake or pond. The land is uneven still, rising and falling, a giant rucked quilt, and so the valley floor remains invisible. The gloaming has arrived, and with it the masking power of shadow. He had better move quickly now before he becomes enshrouded in darkness in the middle of nowhere.

Life had all seemed so straightforward at one point for him, he thinks: career, friends, marriage, children. Jake had finished law school fifteen years before, and been recruited to join the police as part of a special fast-track system designed to attract graduates with law degrees. He had met Faye four years into the job. She was a solicitor, who ate lunch on a bench outside the magistrates’ court whenever she had a case there. He liked her red-brown hair, almost copper, and the way she wore Converse trainers with a work skirt. Jake’s job brought him to the vicinity a lot, and he began timing his lunchbreaks to match hers, sitting on a nearby bench, pretending to read. In the end, she had approached him, when one chilly October afternoon the wind scattered her lunch wrappers, blustering them in his direction. He wasn’t in uniform – that part of the job had been fast-tracked as well – but he still looked official, unrelaxed somehow. She knew he was a policeman, she said, because his eyes were never still, his body was taut even when he was trying to appear loose. She liked that about him, she often told him, even after they started going out; he was never sleepy or acquiescent. He was switched on like a light, and she relished never having to be in the dark any more.

They felt right together from the very next day when they shared her bench for lunch. After the third time, they both skipped work to go back to her flat, the thrill of breaking the rules a halo to the thrill of seeing each other’s unclothed bodies. They clicked in the bedroom as they had on the bench. It felt simple and easy. And perhaps it was all too easy: the next couple of years, the compatible jobs, the shared friends from the big London law schools. They were married at thirty, a good age they told each other, life still very much to come, wandering freedoms stored where they should be, in the past. A shared desire to embrace life’s encumbrances as they arrived. They pooled resources for a nice suburban house. Jake’s parents had died before he graduated, shocking him into self-reliance, giving him a financial push into comfortable adulthood. And now their own children would come, more encumbrances, more pressure, but also something to cherish and build upon.

Children never came. Only hope, then disappointment. Clutching her hand as the spasms racked her body. The trips to the hospital, after uncertain pains led to clouts of dark blood on the floor, a miniature crime scene. Doctors either brisk or baffled.

Everyone knows someone who has had a miscarriage before producing healthy children. The loss is awful, but not out of the ordinary; it is within life’s reasonable expectations. But then a second miscarriage, then a third. The tests suggesting something not quite right. They didn’t click after all. They couldn’t fuse when it mattered the most.

As Jake descends into the dusk, the ground dark green in pools around him, he sees it: a farmhouse buried deep into the dip of the land, an L-shape on its side, with the broad front before him. It is dark brown in the dimness, splotched with ivy in parts, a huge birch tree to the side standing guard. He runs down the final part of the path, his heart suddenly racing. He can feel the house’s emptiness like a palpable presence, something thick and unyielding. It is aloof to his existence, which is somehow reassuring. There is solidity here, he feels, something to cling to. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved