- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

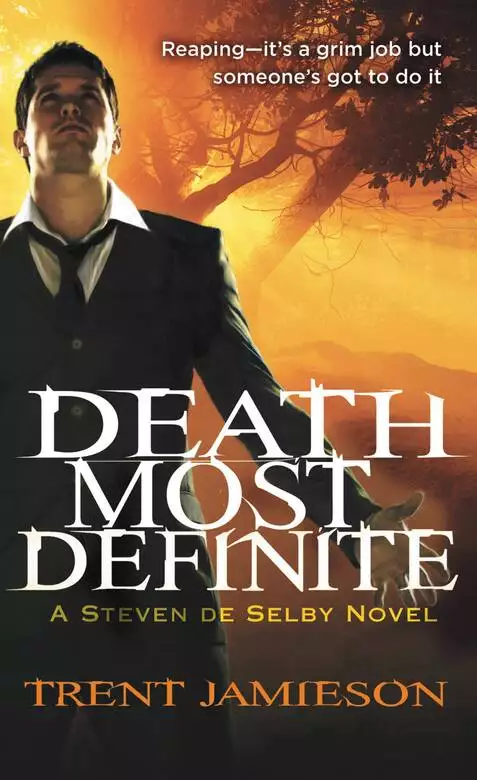

Synopsis

Steven de Selby has a hangover. Bright lights, loud noise, and lots of exercise are the last thing he wants. But that's exactly what he gets when someone starts shooting at him. Steven is no stranger to death-Mr. D's his boss after all-but when a dead girl saves him from sharing her fate, he finds himself on the wrong end of the barrel. His job is to guide the restless dead to the underworld but now his clients are his own colleagues, friends, and family. Mr. D's gone missing and with no one in charge, the dead start to rise, the living are hunted, and the whole city teeters on the brink of a regional apocalypse-unless Steven can shake his hangover, not fall for the dead girl, and find out what happened to his boss- that is, Death himself.

Release date: July 17, 2010

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 338

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death Most Definite

Trent Jamieson

She shouldn’t be here. Or I shouldn’t. But no one else is working this. I’d sense them if they were. My phone’s hardly helpful.

There are no calls from Number Four, and that’s a serious worry. I should have had a heads-up about this: a missed call, a

text, or a new schedule. But there’s nothing. Even a Stirrer would be less peculiar than what I have before me.

Christ, all I want is my coffee and a burger.

Then our eyes meet and I’m not hungry anymore.

A whole food court’s worth of shoppers swarm between us, but from that instant of eye contact, it’s just me and her, and that

indefinable something. A bit of deja vu. A bit of lightning. Her eyes burn into mine, and there’s a gentle, mocking curl to her lips that is gorgeous; it hits me

in the chest.

This shouldn’t be. The dead don’t seek you out unless there is no one (or no thing) working their case: and that just doesn’t

happen. Not these days. And certainly not in the heart of Brisbane’s CBD.

She shouldn’t be here.

This isn’t my gig. This most definitely will not end well. The girl is dead; our relationship has to be strictly professional.

She has serious style.

I’m not sure I can pinpoint what it is, but it’s there, and it’s unique. The dead project an image of themselves, normally

in something comfortable like a tracksuit, or jeans and a shirt. But this girl, her hair shoulder length with a ragged cut,

is in a black, long-sleeved blouse, and a skirt, also black. Her legs are sheathed in black stockings. She’s into silver jewelery,

and what I assume are ironic brooches of Disney characters. Yeah, serious style, and a strong self-image.

And her eyes.

Oh, her eyes. They’re remarkable, green, but flecked with gray. And those eyes are wide, because she’s dead—newly dead—and

I don’t think she’s come to terms with that yet. Takes a while: sometimes it takes a long while.

I yank pale ear buds from my ears, releasing a tinny splash of “London Calling” into the air around me.

The dead girl, her skin glowing with a bluish pallor, comes toward me, and the crowd between us parts swiftly and unconsciously.

They may not be able to see her but they can feel her, even if it lacks the intensity of my own experience. Electricity crackles up my spine—and something else, something

bleak and looming like a premonition.

She’s so close now I could touch her. My heart’s accelerating, even before she opens her mouth, which I’ve already decided,

ridiculously, impossibly, that I want to kiss. I can’t make up my mind whether that means I’m exceedingly shallow or prescient.

I don’t know what I’m thinking because this is such unfamiliar territory: total here-be-dragons kind of stuff.

She blinks that dead person blink, looks at me as though I’m some puzzle to be solved. Doesn’t she realize it’s the other

way around? She blinks again, and whispers in my ear, “Run.”

And then someone starts shooting at me.

Not what I was expecting.

Bullets crack into the nearest marble-topped tables. One. Two. Three. Shards of stone sting my cheek.

The food court surges with desperate motion. People scream, throwing themselves to the ground, scrambling for cover. But not

me. She said run, and I run: zigging and zagging. Bent down, because I’m tall, easily a head taller than most of the people

here, and far more than that now that the majority are on the floor. The shooter’s after me; well, that’s how I’m taking it.

Lying down is only going to give them a motionless target.

Now, I’m in OK shape. I’m running, and a gun at your back gives you a good head of steam. Hell, I’m sprinting, hurdling tables,

my long legs knocking lunches flying, my hands sticky with someone’s spilt Coke. The dead girl’s keeping up in that effortless

way dead people have: skimming like a drop of water over a glowing hot plate.

We’re out of the food court and down Elizabeth Street. In the open, traffic rumbling past, the Brisbane sun a hard light overhead.

The dead girl’s still here with me, throwing glances over her shoulder. Where the light hits her she’s almost translucent.

Sunlight and shadow keep revealing and concealing at random; a hand, the edge of a cheekbone, the curve of a calf.

The gunshots coming from inside haven’t disturbed anyone’s consciousness out here.

Shootings aren’t exactly a common event in Brisbane. They happen, but not often enough for people to react as you might expect.

All they suspect is that someone needs to service their car more regularly, and that there’s a lanky bearded guy, possibly

late for something, his jacket bunched into one fist, running like a madman down Elizabeth Street. I turn left into Edward,

the nearest intersecting street, and then left again into the pedestrian-crammed space of Queen Street Mall.

I slow down in the crowded walkway panting and moving with the flow of people; trying to appear casual. I realize that my

phone’s been ringing. I look at it, at arm’s length, like the monkey holding the bone in 2001: A Space Odyssey. All I’ve got on the screen is Missed Call, and Private Number. Probably someone from the local DVD shop calling to tell

me I have an overdue rental, which, come to think of it, I do—I always do.

“You’re a target,” the dead girl says.

“No shit!” I’m thinking about overdue DVDs, which is crazy. I’m thinking about kissing her, which is crazier still, and impossible.

I haven’t kissed anyone in a long time. If I smoked this would be the time to light up, look into the middle distance and

say something like: “I’ve seen trouble, but in the Wintergarden, on a Tuesday at lunchtime, c’mon!” But if I smoked I’d be

even more out of breath and gasping out questions instead, and there’s some (well, most) types of cool that I just can’t pull

off.

So I don’t say anything. I wipe my Coke-sticky hands on my tie, admiring all that je ne sais quoi stuff she’s got going on and feeling as guilty as all hell about it, because she’s dead and I’m being so unprofessional.

At least no one else was hurt in the food court: I’d feel it otherwise. Things aren’t that out of whack. The sound of sirens builds in the distant streets. I can hear them, even above my pounding heart.

“This is so hard.” Her face is the picture of frustration. “I didn’t realize it would be so hard. There’s a lot you need—”

She flickers like her signal’s hit static, and that’s a bad sign: who knows where she could end up. “If you could get in—”

I reach toward her. Stupid, yeah, but I want to comfort her. She looks so pained. But she pulls back, as though she knows

what would happen if I touch her. She shouldn’t be acting this way. She’s dead; she shouldn’t care. If anything, she should

want the opposite. She flickers again, swells and contracts, grows snowy. Whatever there is of her here is fracturing.

I take a step toward her. “Stop,” I yell. “I need to—”

Need to? I don’t exactly know what I need. But it doesn’t matter because she’s gone, and I’m yelling at nothing. And I didn’t

pomp her.

She’s just gone.

That’s not how it’s meant to happen. Unprofessional. So unprofessional. I’m supposed to be the one in control.

After all, I’m a Psychopomp: a Pomp. Death is my business, has been in my family for a good couple of hundred years. Without

me, and the other staff at Mortmax Industries, the world would be crowded with souls, and worse. Like Dad says, pomp is a

verb and a noun. Pomps pomp the dead, we draw them through us to the Underworld and the One Tree. And we stall the Stirrers,

those things that so desperately desire to come the other way. Every day I’m doing this—well, five days a week. It’s a living,

and quite a lucrative one at that.

I’m good at what I do. Though this girl’s got me wondering.

I wave my hand through the spot where, moments ago, she stood. Nothing. Nothing at all. No residual electrical force. My skin

doesn’t tingle. My mouth doesn’t go dry. She may as well have never been there.

The back of my neck prickles. I turn a swift circle.

Can’t see anyone, but there are eyes on me, from somewhere. Who’s watching me?

Then the sensation passes, all at once, a distant scratching pressure released, and I’m certain (well, pretty certain) that

I’m alone—but for the usual Brisbane crowds pushing past me through the mall. Before, when the dead girl had stood here, they’d

have done anything to keep away from her and me. Now I’m merely an annoying idiot blocking the flow of foot traffic. I find

some cover: a little alcove between two shops where I’m out of almost everyone’s line of sight.

I get on the phone, and call Dad’s direct number at Mortmax. Maybe I should be calling Morrigan, or Mr. D (though word is

the Regional Manager’s gone fishing), but I need to talk to Dad first. I need to get this straight in my head.

I could walk around to Number Four, Mortmax’s office space in Brisbane. It’s on George Street, four blocks from where I’m

standing, but I’m feeling too exposed and, besides, I’d probably run into Derek. While the bit of me jittery with adrenaline

itches for a fight, the rest is hungry for answers. I’m more likely to get those if I keep away. Derek’s been in a foul mood

and I need to get through him before I can see anyone else. Derek runs the office with efficiency and attention to detail,

and he doesn’t like me at all. The way I’m feeling, that’s only going to end in harsh words. Ah, work politics. Besides, I’ve

got the afternoon and tomorrow off. First rule of this gig is: if you don’t want extra hours keep a low profile. I’ve mastered

that one to the point that it’s almost second nature.

Dad’s line must be busy because he doesn’t pick up. Someone else does, though. Looks like I might get a fight after all.

“Yes,” Derek says. You could chill beer with that tone.

“This is Steven de Selby.” I can’t hide the grin in my voice. Now is not the time to mess with me, even if you’re Morrigan’s

assistant and, technically, my immediate superior.

“I know who it is.”

“I need to talk to Dad.”

There are a couple of moments of uncomfortable silence, then a few more. “I’m surprised we haven’t got you rostered on.”

“I just got back from a funeral. Logan City. I’m done for the day.”

Derek clicks his tongue. “Do you have any idea how busy we are?”

Absolutely, or I’d be talking to Dad. I wait a while: let the silence stretch out. He’s not the only one who can play at that.

“No,” I say at last, when even I’m starting to feel uncomfortable. “Would you like to discuss it with me? I’m in the city.

How about we have a coffee?” I resist the urge to ask him what he’s wearing.

Derek sighs, doesn’t bother with a response, and transfers me to Dad’s phone.

“Steve,” Dad says, and he sounds a little harried. So maybe Derek wasn’t just putting it on for my benefit.

“Dad, well, ah…” I hesitate, then settle for the obvious. “I’ve just been shot at.”

“What? Oh, Christ. You sure it wasn’t a car backfiring?” he asks somewhat hopefully.

“Dad… do cars normally backfire rounds into the Wintergarden food court?”

“That was you?” Now he’s sounding worried. “I thought you were in Logan.”

“Yeah, I was. I went in for some lunch and someone started shooting.”

“Are you OK?”

“Not bleeding, if that’s what you mean.”

“Good.”

“Dad, I wouldn’t be talking to you if someone hadn’t warned me. Someone not living.”

“Now that shouldn’t be,” he says. He sounds almost offended. “There are no punters on the schedule.” He taps on the keyboard.

I could be in for a wait. “Even factoring in the variables, there’s no chance of a Pomp being required in the Wintergarden

until next month: elderly gentleman, heart attack. There shouldn’t be any activity there at all.”

I clench my jaw. “There was, Dad. I’m not making it up. I was there. And, no, I haven’t been drinking.”

I tell him about the dead girl, and am surprised at how vivid the details are. I hadn’t realized that I’d retained them. The

rest of it is blurring, what with all the shooting and the sprinting, but I can see her face so clearly, and those eyes.

“Who was she?”

“I don’t know. She looked familiar: didn’t stay around long enough for me to ask her anything. But Dad, I didn’t pomp her.

She just disappeared.”

“Loose cannon, eh? I’ll look into it, talk to Morrigan for you.”

“I’d appreciate that. Maybe I was just in the wrong place at the wrong time, but it doesn’t feel like that. She was trying

to save me, and when do the dead ever try and look after Pomps?”

Dad chuckles at that. There’s nothing more self-involved than a dead person. Talking of self-involved…“Derek says you’re busy.”

“We’re having trouble with our phone line. Another one of Morrigan’s ‘improvements’,” Dad says, I can hear the inverted commas

around improvements. “Though… that seems to be in the process of being fixed.” He pauses. “I think that’s what’s happening, there’s a half-dozen people here pulling wiring out of the wall.” I can hear them in the background,

drills whining; there’s even a little hammering. “Oh, and there’s the Death Moot in December. Two months until everything’s

crazy and the city’s crowded with Regional Managers. Think of it, the entire Orcus here, all thirteen RMs.” He groans. “Not

to mention the bloody Stirrers. They keep getting worse. A couple of staffers have needed stitches.”

I rub the scarred surface of the palm of my free hand. Cicatrix City as we call it, an occupational hazard of stalling stirs,

but the least of them when it came to Stirrers. A Pomp’s blood is enough to exorcise a Stirrer from a newly dead body, but

the blood needs to be fresh. Morrigan is researching ways around this, but has come up with nothing as of yet. Dad calls it

time-wastery. I for one would be happy if I didn’t have to slash open my palm every time a corpse came crashing up into unlife.

A stir is always a bad thing. Unsettling, dangerous and bloody. Stirrers, in essence, do the same thing as Pomps, but without

discretion: they hunger to take the living and the dead. They despise life, they drain it away like plugholes to the Underworld,

and they’re not at all fond of me and mine. Yeah, they hate us.

“Well, I didn’t see or sense one in Logan. Just a body, and a lot of people mourning.”

“Hmm, you got lucky. Your mother had two.” Dad sighs. “And here I am stuck in the office.”

I make a mental note to call Mom. “So Derek wasn’t lying.”

“You’ve got to stop giving Derek so much crap, Steve. He’ll be Ankou one day, Morrigan isn’t going to be around forever.”

“I don’t like the guy, and you can’t tell me that the feeling isn’t mutual.”

“Steven, he’s your boss. Try not to piss him off too much,” Dad says and, by the tone of his voice, I know we’re about to

slip into the same old argument. Let me list the ways: My lack of ambition. How I could have had Derek’s job, if I’d really

cared. How there’s more Black Sheep in me than is really healthy for a Pomp. That Robyn left me three years ago. Well, I don’t

want to go there today.

“OK,” I say. “If you could just explain why the girl was there and, maybe, who she was. She understood the process, Dad. She

wouldn’t let me pomp her.” There’s silence down the end of the line. “You do that, and I’ll try and suck up to Derek.”

“I’m serious,” Dad says. “He’s already got enough going on today. Melbourne’s giving him the run-around. Not returning calls,

you know, that sort of thing.”

Melbourne giving Derek the run-around isn’t that surprising. Most people like to give Derek the run-around. I don’t know how

he became Morrigan’s assistant. Yeah, I know why, he’s a hard worker, and ambitious, almost as ambitious as Morrigan—and Morrigan is Ankou, second only to Mr. D. But Derek’s

hardly a people person. I can’t think of anyone who Derek hasn’t pissed off over the years: anyone beneath him, that is. He’d not dare with Morrigan, and only a madman would consider it with Mr. D—you don’t mess with Geoff Daly,

the Australian Regional Manager. Mr. D’s too creepy, even for us.

“OK, I’ll send some flowers,” I say. “Gerberas, everyone likes gerberas, don’t they?”

Dad grunts. He’s been tapping away at his computer all this time. I’m not sure if it’s the computer or me that frustrates

him more.

“Can you see anything?”

A put-upon sigh, more tapping. “Yeah… I’m… looking into… All right, let me just…” Dad’s a one-finger typist. If glaciers had

fingers they’d type faster than him. Morrigan gives him hell about it all the time; Dad’s response requires only one finger

as well. “I can’t see anything unusual in the records, Steve. I’d put it down to bad luck, or good luck. You didn’t get shot

after all. Maybe you should buy a scratchie, one of those $250,000 ones.”

“Why would I want to ruin my mood?”

Dad laughs. Another phone rings in the background; wouldn’t put it past Derek to be on the other end. But then all the phones

seem to be ringing.

“Dad, maybe I should come into the office. If you need a hand…”

“No, we’re fine here,” Dad says, and I can tell he’s trying to keep me away from Derek, which is probably a good thing. My

Derek tolerance is definitely at a low today.

We say our goodbyes and I leave him to all those ringing phones, though my guilt stays with me.

I take a deep breath. I feel slightly reassured about my own living-breathing-walking-talking future. If Number Four’s computers

can’t bring anything unusual up then nothing unusual is happening.

There are levels of unusual though, and I don’t feel that reassured by the whole thing, even if I can be reasonably certain

no one has a bead on me. Something’s wrong. I just can’t put my finger on it. The increased Stirrer activity, the problems

with the phones… But we’ve had these sorts of things before, and even if Stirrers are a little exotic, what company doesn’t

have issues with their phones at least once a month? Stirrers tend to come in waves, particularly during flu season—there’s

always more bodies, and a chance to slip in before someone notices—and it’s definitely flu season, spring is the worst for

it in Brisbane. I’m glad I’ve had my shots, there’s some nasty stuff going around. Pomps are a little paranoid about viruses,

with good reason—we know how deadly they can be.

Still, I don’t get shot at every day (well, ever). Nor do I obsess over dead girls to the point where I think I would almost

be happy to be shot at again if I got the chance to spend more time with them. It’s ridiculous but I’m thinking about her

eyes, and the timbre of her voice. Which is a change from thinking about Robyn.

My mobile rings a moment later, and I actually jump and make a startled sound, loud enough to draw a bit of attention. I cough.

Pretend to clear my throat. The LCD flashes an all too familiar number at me—it’s the garage where my car is being serviced.

I take the call. Seems I’m without a vehicle until tomorrow at least, something’s wrong with something. Something expensive

I gather. Whenever my mechanic sounds cheerful I know it’s going to cost me, and he’s being particularly ebullient.

The moment I hang up, the phone rings again.

My cousin Tim. Alarm bells clang in the distant recesses of my mind. We’re close, Tim’s the nearest thing I have to a brother,

but he doesn’t normally call me out of the blue. Not unless he’s after something.

“Are you all right?” he demands. “No bullet wounds jettisoning blood or anything?”

“Yeah. And, no, I’m fine.”

Tim’s a policy advisor for a minor but ambitious state minister. He’s plugged in and knows everything. “Good, called you almost

as soon as I found out. You working tomorrow?” he asks.

“No, why?”

“You’re going to need a drink. I’ll pick you up at your place in an hour.” Tim isn’t that great at the preamble. Part of his

job: he’s used to getting what he wants. And he has the organizational skills to back it up. Tim would have made a great Pomp,

maybe even better than Morrigan, except he decided very early on that the family trade wasn’t for him. Black Sheep nearly

always do. Most don’t even bother getting into pomping at all. They deny the family trade and become regular punters. Tim’s

decision had caused quite a scandal.

But, he hadn’t escaped pomping completely; part of his remit is Pomp/government relations, something he likes to complain

about at every opportunity: along the lines of every time I get out, they pull me back in. Still, he’s brilliant at the job.

Mortmax and the Queensland government haven’t had as close and smooth a relationship in decades. Between him and Morrigan’s

innovations, Mortmax Australia is in the middle of a golden age.

“I don’t know,” I say.

Tim sighs. “Oh, no you don’t. There’s no getting out of this, mate. Sally’s looking after the kids, and I’m not going to tell

you what I had to do to swing that. It’s her bridge night, for Christ’s sake. Steve, how many other thirty-year-olds do you

know who play bridge?”

I look at my watch. “Hey, it’s only three.”

“Beer o’clock.” I’ve never heard a more persuasive voice.

“Tim, um, I reckon that’s stretching it a bit.”

There’s a long silence down the other end of the phone. “Steve, you can’t tell me you’re busy. I know you’ve got no more pomps

scheduled today.”

Sometimes his finger is a little too on the pulse. “I’ve had a rough day.”

Tim snorts. “Steve, now that’s hilarious. A rough day for you is a nine o’clock start and no coffee.”

“Thanks for the sympathy.” My job is all hours, though I must admit my shifts have been pretty sweet of late. And no coffee

does make for a rough day. In fact, coffee separated by more than two-hourly intervals makes for a rough day.

“Yeah, OK, so it’s been rough. I get that. All the more reason…”

“Pub it is, then,” I say without any real enthusiasm.

I’ve a sudden, aching need for coffee, coal black and scalding, but I know I’m going to have to settle for a Coke. That is,

if I want to get home and change in time.

“You’re welcome,” Tim says. “My shout.”

“Oh, you’ll be shouting, all right.”

“See you in an hour.”

So I’m in the Paddo Tavern, still starving hungry, even after eating a deep-fried Chiko Roll: a sere and jaundiced specimen

that had been mummifying in a nearby cafe’s bain-marie for a week too long.

I had gone home, changed into jeans and a Stooges T-shirt—the two cleanest things on the floor of my bedroom. The jacket and

pants didn’t touch the ground, though, they go in the cupboard until I can get them dry-cleaned. Pomps know all about presentation—well,

on the job, anyway. After all, we spend most of our working day at funerals and in morgues.

I might have eaten something at home but other than a couple of Mars Bars, milk, and dog food for Molly there’s nothing. The

fridge is in need of a good grocery shop; has been for about three years. Besides, I’m only just dressed and deodorized when

Tim honks the horn out the front. Perhaps I shouldn’t have spent ten minutes working on my hair.

Getting to the pub early was . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...