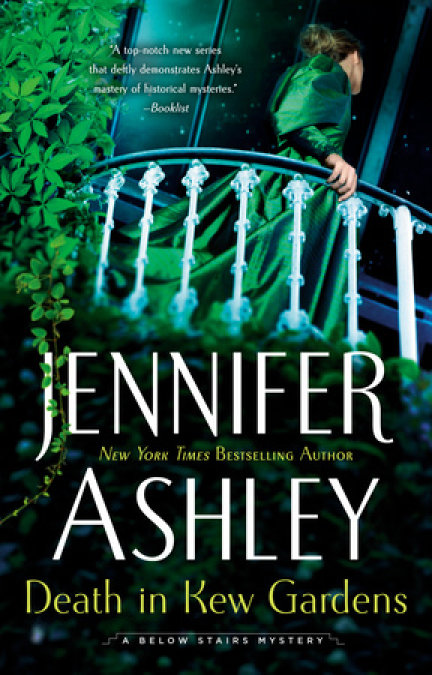

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In return for a random act of kindness, scholar Li Bai Chang presents young cook Kat Holloway with a rare and precious gift—a box of tea. Kat thinks no more of her unusual visitor until two days later when the kitchen erupts with the news that Lady Cynthia's next-door neighbor has been murdered.

Known about London as an Old China Hand, the victim claimed to be an expert in the language and customs of China, acting as intermediary for merchants and government officials. But Sir Jacob's dealings were not what they seemed, and when the authorities accuse Mr. Li of the crime, Kat and Daniel find themselves embroiled in a world of deadly secrets that reach from the gilded homes of Mayfair to the beautiful wonder of Kew Gardens.

Release date: June 4, 2019

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death in Kew Gardens

Jennifer Ashley

Copyright © 2018 Jennifer Ashley

Chapter One

September 1881

The Chinese gentleman ran from between the carriages packed the length of Mount Street and straight into my path. I had no chance—he emerged so suddenly and without my seeing him that I barreled directly into the poor man.

My basket full of produce slammed into his narrow belly, knocking from his feet. He landed on the cobblestones in a tangle of limbs and fabric.

I shoved my basket at my assistant, Tess, and bent over the unfortunate man.

“My dear sir, I do beg your pardon—you popped out so quickly.” I thrust my hands down to him, intending to help him to his feet.

Instead of accepting my assistance, the man cringed from me, his face screwing up in abject fear.

“Come now,” I said, softening my voice. “You can’t stay on the cobbles—they’re full of mud and muck.”

The man hesitated, still afraid, so I firmly took hold of him and hauled him to his feet.

He was small boned and light, easily lifted, but I felt strength under his garments. Once he was standing upright, I saw that he was a few inches taller than I, dressed in a silk robe that fell to his feet, the sleeves so wide his hands would disappear if he folded them together.

His round cap had fallen to the ground, revealing a head that was quite bald from forehead to the top of his skull. As though to make up for the lack of hair in front, a thick braid hung down his back to his knees, and a beard curled to his chest.

His robe was a deep blue, with birds and vines embroidered on the hem in rich yellow and green. The colors were muted from dust, rain, and London grime, but the garment must have once been lovely.

The Chinese gentleman finally lost his agitation and looked at me directly. He was not a young man, middle aged perhaps, though his hair and beard held little gray and his face bore only a few lines. But his eyes, which were dark brown, nearly black, contained a weight of years greater than my own, an understanding that comes from experiencing life, all its tragedies and triumphs. He had an air of supreme confidence that even falling to a London street could not erase.

This gentleman stared at me a moment longer before he tucked his hands into his sleeves, dropped his gaze, and gave me a slight bow. “Forgive me, madam.”

“Not at all,” I said briskly. “I knocked you over, sir, so I ought to apologize. Do take care as you walk about. The drivers do not go as cautiously as they should, and they can’t always stop their heavy drays in time. I would hate to think of you lying hurt on the street.”

He listened to my speech without blinking, though he transferred that keen gaze to my left shoulder. I sensed Tess behind me, gawping at the man with no sense of her own rudeness.

“Please accept my many apologies, good lady,” he said.

His manners were exquisite, such a refreshing change from those of men who had no intention of being courteous to a mere cook.

“No harm done,” I said. “Now, you must excuse me, sir. I need to walk past you, and there is very little room on the road today.”

The corners of the man’s eyes crinkled with good humor. As he bent to sweep up his cap, I saw razor scars on the top of his scalp from many years of shaving back his hair.

He gave me a final nod and darted off, moving swiftly between the carriages, around the corner to Park Street. I watched until he disappeared from sight then I took my basket from Tess, and we walked on.

“Well, that was interestin’,” she said in her cheery tones. “You don’t see many Chinamen in these parts. I’m surprised he’s allowed to walk in Mayfair.”

I shrugged. “He likely works for a family here, as we do.”

Even as I spoke, I felt a frisson of doubt. I’d been employed at the Rankin house on Mount Street long enough to have become acquainted with the servants in the homes around it, and none employed a Chinese gentleman.

Also, I did not believe he was a common laborer, as were many Cantonese who had come to London to escape poverty or war in their own country. While the gentleman had been afraid when I’d first knocked him down, he’d stood proudly on his feet, without the slump of shoulders of a menial. His faded robe had once been fine, the touch of the silk like gossamer.

“I’d never be Chinese,” Tess said, swinging her basket. “I hear their women stuff their feet into tiny little shoes.” She kicked out her long foot in its high laced boot. “Can’t work if you do that.”

“You couldn’t help being Chinese if your parents were,” I pointed out. “And the women in China from our walk of life work just as hard as we do.”

“If you say so, Mrs. H.,” Tess said. She crowded close and tucked her hand under my arm. “We’re packed in tight today, ain’t we? Her ladyship next door has no business inviting so many to her house for an afternoon. She’s ruined the whole street.”

Lady Harkness, wife of a knight of the realm, was holding a gathering today to show off her husband’s exquisite and unusual garden, full of plants he’d brought home from his years in the Orient. As it was September, most families of note were off in the country, hunting foxes or shooting birds flushed out by their servants, so but Lady Harkness still managed to fill her gathering. Her husband was decidedly middle class and possibly lower, said Mrs. Bywater, the mistress of my house, with a sniff. Sir Jacob been given a knighthood for services to the Empire, but he’d been born a tradesman in Liverpool.

Regardless of his beginnings, his wealth had brought him much prestige. The number of fine carriages that lined Mount Street and wrapped around the corner showed that his humble beginnings had been forgiven.

Not only did the waiting carriages jam up the works, but carts, wagons, and foot traffic served to clog the area further. Even the most elegant corner of London was a thoroughfare to somewhere else.

Mrs. Bywater was attending the garden party, in spite of her snobbishness about Sir Jacob and his wife. So was her niece, Lady Cynthia, with whom I’d formed a friendship. Both ladies wanted a look at the strange plants Sir Jacob had brought back from his many years in foreign parts. Lady Cynthia would tell me later about Lady Harkness’s do, most likely how horrifically wearying it had been.

For now, I had to get supper on the table for the family when they returned and for the entire body of servants—a dozen of us—who kept the Mount Street house running efficiently.

I entered the kitchen, exchanging coat and hat for apron, and began to sort through the comestibles, my encounter with the Chinaman fading to the back of my mind.

While Lord Rankin, a baron, owned the house where I lived and worked, he allowed Lady Cynthia, sister of his deceased wife, and her aunt and uncle, the Bywaters, to occupy the house while he dwelled in Surrey. Cynthia’s aunt and uncle had moved in to chaperone her, and also to keep her behavior in check—at least Mrs. Bywater considered this to be part of her duty. She and her husband wished to get Cynthia married off, out of harm’s way, but Cynthia, so far, had resisted.

The family had remained in residence through the sticky, smelly, uncomfortable London summer. Mr. Bywater always had much business in the City, and Lady Cynthia refused to return to her father’s house. Therefore, my duties had not eased during the hot months, and the kitchen had become like the devil’s anteroom.

Tess and I and the rest of the staff had sweated and struggled, our tempers short. A walk outside had scarcely brought any relief, as the heat enveloped the entire city. At least we were mercifully away from the river and its stink.

September brought welcome coolness and abundance as farmers began to cart in the harvest. Potatoes and apples gradually dominated the vendors’ carts, as well as walnuts and game from the countryside—partridges to venison. Mr. Bywater did not hunt or shoot, but he had friends who sent him whole birds or meat packed in paper and sawdust. Such a savings, Mrs. Bywater never failed to state.

One lesson the penny-pinching Mrs. Bywater learned, however, through the long, roasting summer, was that we truly needed a housekeeper.

Mr. Davis, the butler, and myself had taken on much of the housekeeping duties, but I was too busy cooking, Mr. Davis too busy tending to the wine, silver, and service at table, to take care of much else. Discipline deteriorated among the maids and footmen, and tasks did not get done. I insisted on a large share of the household budget for food, but Mr. Davis wanted it for the master’s wine and brandy. We quarreled frequently, and Mrs. Bywater lost her patience with us.

Mr. Davis told me, triumphantly, a week ago, that Mrs. Bywater had finally broken down and asked an agency to send her candidates for a housekeeper. She hadn’t found one she liked yet, but at least she’d begun the proceedings.

Until then, it fell to me to go over the household accounts, keep inventory of the food, supervise the kitchen staff, and cook until my hands were sore, burned, and abraded.

Tess had proved to be quite capable, learning what I taught her quickly, and was beginning to master recipes and more complicated cooking techniques. She’d been scrubbing floors before I’d taken her on—a sad waste of talent. She’d make a fine cook after more training.

I did not muse on my encounter with the Chinese gentleman the rest of that day, as I had much to do. The next day was also particularly busy, and by the time I prepared the evening meal, I was short tempered and exhausted. Mr. Davis blamed me for a missing bottle of wine—had I put it into my sauce by mistake?

When Charlie, the kitchen boy, spotted the wine behind a stack of greens, had Mr. Davis apologized and owned he’d been wrong? No, he’d sniffed, tucked the bottle under his arm, given Charlie a half-hearted clout on the ear, and stalked away.

I could only shake my head and return to my sauté pan, hoping I hadn’t ruined my sole in butter sauce. The butter had to brown, not burn, or the entire dish was spoiled.

Mr. Bywater liked his supper the moment he returned home, and we were a bit behind with the soup and greens. I thickened the soup with flour instead of letting it reduce, tossed in some cream and a good handful of salt, and sent it up.

Then Emma, the downstairs maid, spilled half my perfected butter sauce on the floor, and fell to weeping. I plunked the rest of the meal onto platters to go up in the dumbwaiter, told Tess to see to the staff’s supper, caught up a basket, and went out through the scullery.

Cool air touched my face as I walked up the stairs to the night, and I breathed a sigh of relief. I usually did not mind my life as a cook, but at times I found it trying. I reminded myself of the virtue of hard work and the fact that I was saving my shillings for the day I could reside with my daughter and run a little tea shop, the two of us living in bliss. Sometimes this vision helped, but tonight, peace eluded me.

In spite of my pique, I hadn’t forgotten those in more need than myself. My basket held scraps I’d saved from the meal—greens too wilted for the dining room, trimmings of cooked meat or fish sliced off for symmetry, fruit too squashed to look fine in the bowl, and dried ends of yesterday’s cake.

The few who gathered outside, knowing I would appear with my basket, swarmed to me with gratefulness. I handed out the food in pieces of towel that would have only gone into the rag bag.

A slim figure joined those in the shadows. I always met the beggars exactly between the streetlamps, where the darkness was greatest. The poor things feared the light, knowing they could be arrested for being unemployed and hungry.

I turned to the newcomer with my last bundle of scraps. “Now, sir, get that inside you, and you’ll feel better . . . Oh.”

I was surprised to see my Chinese gentleman from the day before. His long beard was a wisp against his robes, the blue of the silk black in the shadows.

He held out a box to me, a small wooden casket. “Please,” he said. “A gift for you.”

I held up my hands. “No, no, you do not need to give me anything.”

“You did me a kindness, madam. Allow me to thank you by doing one for you.”

“You are courteous,” I said, softening. “And I thank you, but I cannot possibly accept it. A gentleman does not give gifts to a lady, especially one he is not acquainted with. I am not certain of your customs in China, but in England, I am afraid that is the case.”

His eyes glinted as he raised his head, and I saw in them a flash of hurt. I felt contrite—I must have insulted him.

I gentled my tone. “Forgive me. I know it must be difficult being far from home.” I’d never been farther than Cornwall, and though I’d found it lovely, I’d longed to return to London with all my might.

To my concern, his eyes filled with tears. “Indeed.” The sadness in his voice tugged at me. “Very difficult.”

I put an impulsive hand on his arm. “My dear sir, I am so sorry. Might you tell me your name? Then you would know at least one person in London. I am Mrs. Holloway.”

He hesitated, gazing at my hand on his arm. I lifted it quickly, wondering if I’d just insulted him again.

“Li,” he said after a moment. “That is my name.”

“Excellent. Well, Mr. Li, now that we are friends, perhaps I can accept the gift you are so generously bestowing. As long as it is not too extravagant, mind.”

The box was small and did not look very costly, but one never knew what was inside boxes until one opened them.

“It is, as you say, a trifle.”

“If you promise,” I said doubtfully.

A smile pulled at the corners of Mr. Li’s mouth. “It is tea.”

“Oh,” I said, pleased. A good cup of tea was a fine thing. “Thank you, Mr. Li. You are kind.”

“It is you who are kind, Mrs. Holloway.”

I decided to end our effusion of politeness by taking the box. The wood was intricately carved but the box was light.

“There now,” I said, not certain how to gracefully take my leave. “I ever you have need of a friend, Mr. Li, I am the cook in the house yonder.” I pointed to it. “I am extremely busy most of the time, but if you do need help, do not hesitate . . .”

I trailed off, realizing I spoke to empty air. Mr. Li had slipped into the shadows as I’d pompously waved at the great house. I glimpsed him walking swiftly along Mount Street toward Berkeley Square, but I soon lost sight of him in the lowering mist. The beggars had taken their food and gone, and I stood alone.

Chuckling at myself, I tucked the box into my basket and returned home.

I left the basket in the larder, but the tea I took upstairs to my bedchamber and locked into the bottom drawer of my bureau. It was my tea, and I would not risk Mr. Davis happening upon it, and my gift disappearing down his throat.

In the morning, Sunday, as I was about to pour out the batter-like dough for the breakfast crumpets, Lady Cynthia rushed into the kitchen.

She did this often, as she found the company of her aunt and uncle stifling and many of their guests a bore. The accepted life of a spinster was not for her. She demonstrated this today by appearing in trousers—riding breeches to be exact—with boots to her knees and a waistcoat, long-tailed coat, and neatly tied cravat.

As she kept to her feet, I remained standing, as did Tess, Charlie, who tended the fire, and Emma, who’d come in to help convey breakfast to the dining room.

“I thought you’d like to know right away, Mrs. H.,” Lady Cynthia said. “There was a death last night. Sir Jacob Harkness.”

“Oh, dear.” I’d never liked Sir Jacob—what little I’d seen of him—but I felt a dart of sympathy. Sudden death was always sad, difficult for the family. “Poor man. Was he ill?”

“No, indeed. Fit as a proverbial fiddle.” Lady Cynthia’s voice was as robust as ever. “That’s why I’m telling you. He was murdered. Stabbed through the heart in his own bedchamber. The police are even now swarming the house next door, questioning everyone in sight.”

Chapter Two

I stared at her in shock. The others froze in consternation, Tess behind me, Charlie poised with a shovelful of coal, Emma at the dumbwaiter.

“Good heavens,” I exclaimed. “What happened? Were they robbed?”

“Don’t know,” Cynthia admitted. “I have my knowledge from Sir Jacob’s valet, Sheppard, who came charging around to tell Uncle, most upset. Lady Harkness is in hysterics, and Aunt Izzie has gone to calm her down. Not the person I’d want with me if I were upset, but there was no stopping her.”

Before I could ask more, the back door banged open, and one of the housemaids from next door burst in. “Oh, Mrs. Holloway, Mrs. Finnegan says, will you come?”

Mrs. Finnegan was the Harkness family cook, and she was disorganized on the best of days. She would be in a right mess now.

I glanced at the pots burbling on the stove, boiling the eggs for the family’s and servants’ breakfasts. The crumpet dough rested on the table, ready to be poured into rings on the stove. “Tess . . .”

“Go on,” she said, waving me off. “I can manage. I know you like to be in the thick of things.”

“Not at all,” I said coolly. “I’m certain their kitchen is at sixes and sevens, and I ought to help.”

“Right you are, Mrs. H.” Tess winked at me and moved to take over the crumpets.

“Not too long on the hob,” I told her. “Or they’ll burn on the outside and be raw on the inside.” I called the last words as I hurried down the passage to the housekeeper’s parlor, where I kept my coat.

“I know.” Tess’s voice rose behind me. “I do pay attention when ya teach me things.”

I snatched my coat from its peg and put it on over my apron. I saw no sign of Mr. Davis in the hall or in his pantry—I guessed he was upstairs watching the footmen ready the dining room for breakfast.

Lady Cynthia waited for me at the back door and accompanied me out through the scullery to the street.

A small crowd had gathered before the house next door. They glanced with envy at Lady Cynthia and me as I walked around the railings and down the stairs to the kitchen. Cynthia continued to the front door, where she was quickly admitted.

I’d been correct about the kitchen being in chaos. Mrs. Finnegan sweated desperately over a stove that was nowhere near as well ordered as mine. She shouted commands at a kitchen maid who wept and paid no attention.

The table, strewn with flour and blotched with butter and grease, held a pile of kippers on its wooden surface. I suppressed my distaste. I would have put the lack of cleanliness down to the violent crime in the household, but I’d been in Mrs. Finnegan’s kitchen before.

“Mrs. Finnegan,” I said loudly over the fizzling stove and the maid’s histrionics.

Mrs. Finnegan swung around. She was a large woman with greasy black hair stuffed into a soiled cap and burn marks on her cheeks. She was not an unfriendly woman, but now she glared at me.

“There you are, Mrs. Holloway. You took your time fetching her, Jane. Her ladyship wants breakfast for all the coppers rushing over the house, accusing the servants of stabbing the master to death.”

“I’ve only just heard.” I stripped off my coat, found a place to hang it out of danger of spattering fat, and took up a towel that looked somewhat clean. “Cease your crying, child,” I said kindly to the kitchen maid. “Fetch a plate for these kippers, and scrub off the table. The best cure for an upset is hard work.”

The kitchen maid obviously did not agree, but she hurried to obey.

While the maid cleaned up the mess, I looked over the boiling eggs, the bacon frying in an inch of grease, potatoes bubbling in another pot, and a basket of yellow onions starting to brown.

“If you’re feeding policemen, make a nice hash,” I suggested to Mrs. Finnegan. “They won’t expect to sit down to a polished meal.”

Mrs. Finnegan gave me a surly nod. “Best get to chopping those onions, then. I have pork from yesterday’s roast, and plenty of scone scraps from the garden party.”

The leftover scones proved to be in another basket, hard and stale. But stale breads could be added to other dishes to give them body.

I moved the onions to the table, which the maid had finished wiping, picked out a few of the best ones, and fell to slicing.

“Tell me what happened,” I said.

“I don’t know, do I?” Mrs. Finnegan jerked a greenish copper pot from the rack above her head and slammed it to the stove, dumping in the bacon she fished from the frying pan. “I was starting the breakfast when Sheppard bursts in, shrieking the master was dead. Next thing I know, housekeeper is hailing a constable, and in they come, demanding us to tell them whether we’d killed the master. I never see the master, I say to them. I keep to my kitchen and my little cubby for sleeping. But you know what coppers are like. Everyone is a villain, in their minds.”

I had encountered such policemen before, so I could not argue. “Jane—what do you know about it?”

Jane, the maid who’d retrieved me from next door, shook her head. “Nothing much, ma’am. I was on the upstairs landing, dusting as usual, when Mr. Sheppard comes rushing down, yelling his head off. When I peeked up the stairs, I see the mistress coming out of the master’s chamber, Mrs. Redfern holding her up. I went down to the kitchen to find out what was the matter, and Mr. Sheppard is here, babbling that the master is dead. Cook had to give him brandy to calm him down.”

Mrs. Redfern was the Harkness housekeeper. The household did not employ a butler—Mr. Sheppard filled in the butler’s duties.

“And now the police are questioning all of us,” Mrs. Finnegan said sourly. “The master went out last night, so Sheppard said, to that Kew Gardens place, which the master gives so many of his plants to. They’re asking when he came home, who did he meet, did anyone return with him? As though we take all the master’s particulars.”

“Where is Mr. Sheppard now?” I asked.

“Policemen have him cornered upstairs,” Jane said. “They think he did it. But he couldn’t have, could he? Mr. Sheppard faints when he sees a mouse.”

But a man afraid of mice might not necessarily be afraid to fight or kill, especially when threatened. I agreed, however, it was highly unlikely that timid Mr. Sheppard had decided to murder his master and then run downstairs to announce the fact.

“The house wasn’t broken into?”

“No one has said that.” Mrs. Redfern chose to enter the room as I asked the question. “Good morning, Mrs. Holloway.”

“Mrs. Redfern.” I gave her a nod. She and I were not on the most cordial terms, likely because we both knew our own minds and were not willing to retreat from our opinions.

Jane, who should have returned to her duties upstairs, curtsied stiffly to Mrs. Redfern and hurried contritely out.

“Very kind of you to assist us, Mrs. Holloway,” Mrs. Redfern said. “But scarcely necessary.” She gave me a sharp look from eyes that were intelligent and watchful.

“On the contrary,” I answered. “Mrs. Finnegan is rushed off her feet. I have suggested a hash for the constables, since you need to feed them. Browned onions give it a nice flavor.”

As I spoke, I chopped the onions into a careful dice, my knife making a tick, tick, tick sound on the table.

Mrs. Redfern folded her arms, the keys on her belt clanging. “Since I know you will be eager to learn all, I will tell you this, Mrs. Holloway. Sheppard entered the master’s chamber early, as Sir Jacob likes to rise and breakfast at six. Sheppard found the master in bed, in his dressing gown and nightshirt, with a stab wound in the middle of his chest amidst a quantity of blood. Turned the white sheets quite red, he said.”

I have a good imagination, and the description made me a bit queasy. The kitchen maid sank into a chair—a maid should never sit when senior staff is present, but I do not think the poor girl knew up from down at the moment.

Mrs. Redfern ignored her and continued. “Sheppard lost his nerve and bolted out of the room, shouting hysterically, which woke the mistress, who, I am sorry to say, ran in and saw her husband lying there, dead. I put Lady Harkness back to bed, she being upset, as you can imagine, and went out and found the constable on his beat. He fetched a sergeant, and he fetched a fellow from Scotland Yard, who is now investigating. One of the ground-floor windows was open, so it is likely the culprit entered and exited that way.”

Mrs. Finnegan dumped cut-up pork into the pot with the bacon and scattered flour over all. I would have added some mushroom ketchup and cloves to give the hash flavor, but Mrs. Finnegan only poured in a handful of salt and mashed everything together.

“The police should stop accusing us of doing him in,” Mrs. Finnegan said darkly. “Next thing you know, they’ll cart the lot of us to jail.”

The kitchen maid gasped again. I wiped my hands and patted her shoulder. “If it’s an open window, they’ll believe it an intruder.” I longed to examine the window in question, but I would have to invent an excuse to go upstairs. “Stands to reason. Why would any of you murder Sir Jacob?”

Mrs. Redfern’s lips pinched. “Nothing has been stolen, that we can find. Sir Jacob’s watch and purse with his money were in their places, all as should be. But the master never made a secret that he left us each a small legacy in his will, so of course, one of us killed him for our fifty guineas. Or the mistress did it for all the money he’d leave her.” Her icy stare told me what she thought of these theories.

Sir Jacob had certainly been generous—fifty guineas was a good sum, enough to ease a person’s way in the world. I’d observed while working in great houses that often those who had little or started with little were more lavish and openhanded than those who were used to wealth. I’d known the cook to a duke who’d nearly beggared the woman while he lived in ease upstairs, while a man who started in the gutter paid his servants handsomely.

“That’s as may be,” I said. “But none of the servants would have reason to climb in through the window. And if you are like me, you prefer to be fast asleep in the middle of the night, not skulking about the house with a knife.”

The kitchen maid nodded fervently, and Mrs. Finnegan looked relieved.

I returned to my task of preparing the onions and carried them to the stove to brown. I advised Mrs. Finnegan to add the meat and gravy she’d just made to the onion pan, and though she stared at me in puzzlement, she obeyed. We added the potatoes after that, stirring all together and letting the hash sizzle.

“Why did your master go to Kew Gardens in the middle of the night?” I asked Mrs. Redfern. “Surely, the place would be shut.”

“It wasn’t the middle of the night,” Mrs. Redfern answered. “It was seven of the clock. Sir Jacob bade Sheppard fetch a hansom, and off they went. Sheppard accompanies him everywhere. He says that once they were there, he lost the master in the fog for a few minutes. He swears he saw him talking to someone off in the mist, but he can’t be certain. They came home just before nine, and Sir Jacob went to bed.”

“I see.” I briefly wondered whether the person Sir Jacob met at Kew had followed him home and committed the deed.

Then again, the journey to Kew might have nothing to do with his death—if Sir Jacob shared his exotic plants with th

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...