- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

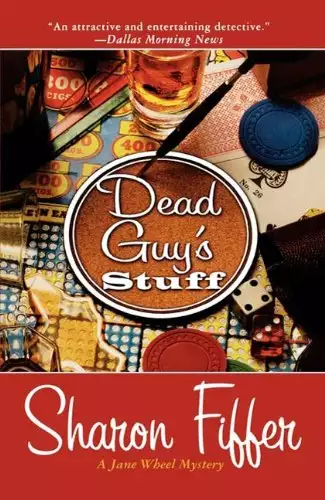

Fresh on the heels of Killer Stuff, Sharon Fiffer's auspicious debut, antique "picker" Jane Wheel is making a career out of going through old stuff; it seems she can't get enough of the piles of vintage clothing, kitchen utensils, Bakelite buttons and post cards she finds at estate sales across the Chicago area. What this saloon keepers' daughter loves, though, is not the items themselves but the stories they tell about the lives of their owners.

So needless to say Jane's delighted when a Saturday morning estate sale turns up a serendipitous find: a whole room packed full of 1950's saloon ephemera. As luck would have it, she's been planning to redecorate her parents' pub, still run and recently purchased outright by her folks. Piles of Bakelite darts and dice, countless advertisements from long-defunct liquor suppliers, and, most exciting of all, a bunch of old bar games, employed by untold patrons intent on whiling away the tedious moments in between the sips of so long ago. She makes a deal to buy the whole room, and can't wait to get the stuff back to her hometown.

As she's cataloging her find, however, Jane makes a gruesome discovery. Packed between the glassware and bowling trophies and old photographs she's already fallen in love with, she uncovers one highly personal, unusual and creepy collectible that she is sure the saloon keeper would have preferred to have kept to himself. It sure sparks her curiosity about the saloon owners, and when Jane gets curious nothing's going to stop her. Employing her friends Detective Bruce Oh and fellow junkhound Tim Lowry, as well as her erstwhile husband Charley, Jane sets out to lay bare the secrets of long ago, secrets that even people close to her would rather be kept quiet forever. Packed with as much intrigue and suspense as a long-buried chest in your grandmother's attic, Dead Guy's Stuff is a fantastic sophomore effort from acclaimed promising cozy writer Sharon Fiffer.

Release date: October 6, 2009

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dead Guy's Stuff

Sharon Fiffer

How do you know, Jane Wheel wondered, not for the first time, whether or not your rituals, your own little signature gestures, are celebrations of your individuality and part of your own quirky charm or if they are neurotic tics, proof positive that you suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder?

For example, at estate sales, as Jane warmed up once inside the house, immersed in the possessions of another, she began humming, sometimes quite loudly, as she thumbed through books, rifled drawers, ran her fingers around the edges of bowls and rims of glassware. Humming seemed innocent enough.

What about the constant checking for car keys in one pocket, checkbook and identification in another, and cold cash in a third? Her fourth pocket, upper left, held a small notebook and tiny mechanical pencil that advertised: GOOSEY UPHOLSTERY—TAKE A GANDER AT OUR FABRICS. Under the slogan was the telephone number WELLS 2-5206. Natural enough to check your pockets in a crowd. She did pat them in a special order, but that was probably something to do with muscle memory or neurological instinct. Right, left on the bottom; right, left on the top. Perhaps left-handed people who checked their pockets moved left to right, top to bottom. She would keep an eye on her friend Tim. He was a lefty.

It was 9:00 A.M. and Jane had just received her number for the sale. Doors would open at nine-thirty, so she had some time for her presale voodoo in the car. She patted her pockets, swallowed a sip of her now lukewarm coffee—after all, it had been sitting there as long as she had, two and a half hours, waiting for the numbers.

Pulling out her little notebook, she checked her list. She had a small sketch of a Depression glass pattern that a friend had asked her to look for and several children's book titles that Miriam, her dealer friend in Ohio, was currently searching for. God, she didn't want to have to fight the book people, but Miriam had said condition didn't matter on these. Miriam had a customer who was after illustrations and would remove them from damaged books that the real book hunters would cast aside. Both Jane and Miriam had shuddered at that. They were both strongly against the adulteration of almost any object, unless of course it was already in tatters and one could feel noble about the salvage. A thoroughly moth-eaten coat from the thirties could have its Bakelite buttons removed. Bakelite buckles and clips that had already been damaged and jewelry already broken or deeply cracked could be refashioned, but by god, Martha Stewart, keep your glue gun away from intact buttons and beads.

Jane's list had the other usual suspects. Flowerpots, vintage sewing notions, crocheted pot holders, bark cloth, all her favorites. She was also hunting old Western objects—linens, blankets, lampshades with cowboys and Indians, horse-head coat hooks. Tim's sister had just had a baby boy, and Tim was already planning the upgrade from nursery to toddler's room and had settled on turning this small corner of a suburban colonial into a set from Spin and Marty, the dude ranch serial from the original—the one that mattered—Mickey Mouse Club.

"Not so politically correct, sweetie, but we'll morph into an Adirondack fishing camp if the whole cowboy-Indie thing gets too Village People for the bro-in-law," Tim had said when she'd talked to him earlier in the week.

Jane had only five minutes to write down her Lucky Five. At every house sale, to pass the interminable waiting time, Jane tried to guess by looking at the outside of the house what the inside would hold. She wrote down five objects, and if they were all in the house, she allowed herself an extra fifty dollars to spend for the day. The game didn't exactly make sense, she knew, since if she won, she lost: fifty dollars. But playing the Lucky Five was so satisfying.

She studied the compact Chicago brick bungalow, located a few blocks from Saint Ita's Church. The front sidewalk had cracked, and the brickwork on the front steps was in disrepair. The classified ad had said "a lifetime of possessions," "a clean sale, a full basement," and the most delightful tease of all, "we haven't even unpacked all the boxes."

Jane listed the Lucky Five: Ice-O-Matic ice crusher (with red handle); a volume of Reader's Digest Condensed Books, including a title by Pearl S. Buck; a Bakelite rosary; pink Coates and Clarke seam binding wrapped around a 1931 "spool pet" card.

Jane looked at her watch. She needed another item fast, and she was blank. She punched at her cellular phone.

"Yeah? Talk loud."

Jane could hear a lot of people in the background. Tim must already be inside some sale or at least scrambling for a place in line.

"I need one last thing for my list!" Jane screamed.

"An advertising key ring with a five-digit telephone number!" Tim screamed back.

"Good."

"Green," he added.

"What?" Jane asked.

"Got to be green. When are you coming down here?"

The phone cut out and Jane unplugged it from the lighter and locked it in the glove compartment. It was almost time. She patted her pockets and drained her coffee. Parked just ahead of her was that nasty woman who had once sent her on a wild goose chase, told her about a great sale, and when Jane got to the address it was a vacant lot. Donna, Jane had named her, for no particular reason other than the fact that she liked her enemies to have names.

Did Donna have a lower number? Would she beat Jane through the front door? So what if she does, Jane told herself. She would race through the house with blinders on, allow no distractions, and beat Donna and everyone else to the treasures.

She would make a beeline down the stairs of this sweet brick bungalow on Chicago's northwest side and be drawn magnetically to the current object of her desire—whatever it was. She would know it when she saw it. Maybe a'40s brown leather Hartmann vanity case with intact mirror and clean, sky blue, watered silk lining. Jane would snap the sharp locks that would fly open with a clear pop and find the case filled to the brim with …

With what? This was the good part, the gutwrenching, heart pounding, nerve-racking question. The speculation. The suspense. The mystery of it all. It was why, whenever she went to house sales, flea markets, garage sales, or rummage sales, she tried to come home with at least one box, suitcase, basket, or container filled with unknown stuff. Buttons, pins, broken jewelry, office supplies, fabric scraps, photos, maps, a junk drawer with a handle was what she wanted to carry home and sort through at her own kitchen table.

When a friend once asked her why she bought so many locked metal boxes, so many jammed suitcases, containers that required crowbars, chisels, screwdrivers, picks, and brute force to open, she shrugged. What kind of a person resists a grab bag? Especially when it costs only a dollar or two? Who doesn't want to own a secret?

Charley, her-not-nearly-estranged-enough-but-nevertheless-maybe-soon-to-be-ex-husband, likened her sifting to his own methods in the field searching for fossils.

"We not only collect the bones, we collect the earth around them. We need to know about the plants, the insects, everything that provides us with clues as to how the creature, whatever the particular creature we're excavating, lived," he said, explaining to their son, Nick, the vials of soil that lined the crowded desk in the den where he often worked weekends, despite the fact that he no longer officially lived in the house.

"Like what Mom does with her buttons and stuff, bust …" Nicky stopped himself from even forming the whole thought. He might be only a middle-schooler, but he possessed the cautious wisdom of the child hoping for the reconciliation of his parents. He was savvy enough to stop any remark that might smack of a value judgment on their respective work. He certainly didn't want his mother's relatively new "professional picker" status to be put under his father's microscope.

"But what?" asked Jane, who had been eyeing the bottles of soil herself, thinking that the caps looked like they might be black Bakelite.

Nick shrugged his shoulders and looked at Charley.

"When we're in the field, we're looking for answers to big questions about life on earth, and when Mom is in the field, at an estate sale …"

"Yes, Professor?" asked Jane, coming to full attention. "What is she doing?"

"She's observing how one person or one family operated during their day-to-day lives," Charley said smoothly. "She's gathering the debris of popular culture of the thirties, the forties, whatever. She's keeping field notes on what people saved, what they deemed usable or beautiful. She observes what is still held by our society to be valuable and cycles those objects into the world as artifacts on display at the contemporary extension of the living museum … the flea market tables and antique malls of the Midwest."

"Nicely done, Charley," Jane said, ruffling his uncombed hair.

Nick felt his heart rise, attached to a small, hope-filled balloon. His father would give up the tiny apartment five blocks away from their house and move back home full-time. Nick would not need the doubles on shin guards, basketball shoes, and school clothes that so many of his friends kept in their two separate bedrooms. So far, he had not needed a bedroom at all in his father's shoebox studio. Charley just came over three or four times a week and most weekends to work, eat, sleep, hang out. Nick's friends assured him it wouldn‘t stay that way, all loose and friendly. Pretty soon, they warned him, things would get ugly, doors would be slammed, locks would be changed, and suitcases would be packed. Furniture would most definitely be rearranged.

No, thought Nick. He might only be an adolescent, but he saw how his father looked at his mother while she was watering her plants or dusting her old books or spooning coffee into the pot. He watched Jane follow Charley with her eyes as he crossed back and forth to the large reference books on the dictionary stand in the den. Sure, Nick was only a sixth grader, but he watched television, read books, played video games. His parents were still in love.

Jane hadn't thought much about whether or not she and Charley should make their separation official. In fact, she wasn't sure they were separated enough to give their situation a name. Neither had turned their back on the marriage exactly. Each had turned their shoulders slightly away from the other, picked up a foot to walk, but had not really let it touch the ground, fall into a step.

Yes, Jane had started the slow turn away when she kissed a neighbor last spring and another neighbor had spread it through the block like the plague. But Jane hadn't kissed Jack Balance because she was dissatisfied with Charley or her marriage. She had kissed Jack because she was dissatisfied with herself, with her own predictable life.

Had she wanted things to grow quite as unpredictable as they had? When she found Sandy, Jack's wife, murdered, her new life as a picker drew her deeper and deeper into a world of crime and suspicion. Concentrating on finding the murderer and discovering clues as well as estate sale treasures had prevented her from thinking much about her marriage gone wrong, especially with Charley off on a dig for the summer in South Dakota.

But since he and Nick, now a well-trained and enthusiastic field assistant, had returned from their exploration, the September routine of teaching classes for Charley, school and soccer for Nick, and fall rummage and flea markets for her had lulled all of them into their old routines. Charley still did much of his work at their house. When Jane brought him a cup of tea with lemon while he graded papers in the den, it was the continuation of a long and comfortable habit. Neither saw any compelling reason to alter the current arrangement. Since she was now keeping the irregular hours of a picker rather than the corporate hours of an advertising executive, Jane counted on Charley to cover for her on weekends when she left the house at 4:00 A.M. to line up at estate and rummage sales, flea markets, and auction previews.

Earlier that very morning, she had left Charley sleeping peacefully on the couch in the den when she tiptoed out the front door into the still darkness. Now, sitting in her car, she read over her "wants" lists, both her own and the ones she kept for Miriam in Ohio and Tim in Kankakee, and reviewed the Lucky Five. Tucking the notebook back into its proper pocket, she let her mind wander. She watched the latecomers scurrying out of their vans and trucks to snag a numbered ticket from the roll on the porch of the house, whose contents would soon enough be scavenged and scattered to the four winds, and pondered her "separation" from Charley.

A marriage, she thought, trying to open an old-but-new-to-her Bonnie Raitt CD she had found, still sealed, at a garage sale just last week and stashed in the glove compartment, is a lot like this packaging. Even if you manage to open the wrapping, get a fingernail under a corner fold and make a start, the transparent wrap clings so tenaciously to the plastic cover that it's nearly impossible to get to the music inside. If she and Charley did manage to separate and listen to what played beneath, around, and under their marriage, would they run back to the comfortable togetherness they had shared for fifteen years or move on to new and unsteady beat?

Enough pondering. Hearing the sound of car doors slamming, Jane dropped the still-unopened CD on the seat. Down the street, one door had opened and, as if they were all connected by an invisible wire, each early bird had followed the leader. Dealers, pickers, and bargain hunters opened their trucks and vans and stretched, making their way to the porch, where the busybodies who always bossed everyone around were already checking numbers, lining everybody up.

Jane remembered her first estate sale three years ago all too well. The ad in the paper had said that numbers would be given out at 8:30 A.M. for a 9:00 A.M. opening. Jane had allowed extra time, thinking maybe she should get there around eight-fifteen in order to get a good number. By the time she made it up to the door to receive her ticket, she was number 181. Listening to those around her and making sure she loitered close enough to the door to hear what the low numbers were discussing, she heard one ponytailed man say he had gotten there at five-thirty because he had overslept and that the Speller sisters had beaten him again. He had gestured to two gaunt, gray women who were chain-smoking Marlboro Reds under a tree, staring into space.

It was a complicated stare that Jane had begun to notice on almost all of the regular sale goers. She was still trying to decipher it and, at the same time, mimic it. One part conjuring—let the items we want be inside that house—as if by sheer mental force one could make that china be the correct pattern of Spode, make that lampshade bear the Tiffany signature—and one part dead-eye focus—let the route into and through the house be without distraction. It was the look of an animal wearing blinders, with only the path ahead visible. Jane now practiced her own version of the stare. It might not make the carved Bakelite bracelet appear in the bottom of a basket of cheap junk jewelry, but it kept people from making idle chatter, distracting one from the true and straight path, the purpose of the hunt.

Donna was two numbers ahead of her. Seven to Jane's nine. How had Jane let that happen? She didn't really know her, this small, speedy woman with a crooked mouth and pinball eyes that darted from your face to your purse to whatever object you were holding in your hand, this woman who sent you off to phantom sales.

"What do you do with those buttons?" she had yelled at Jane once at a rummage sale, and Jane had been so taken aback, both by being spoken to at all and by being asked a direct question about the functional value of what she was buying, that she had simply shaken her head and shrugged. Being questioned about a purchase could ruin the moment so thoroughly that it never even occurred to Jane that it would be fun to shop with a partner. To have to discuss why the fabric squares and rickrack looked so appealing, to have to explain why one salt-and-pepper shaker appealed, but not the other, to have to convince someone that people really collected mechanical advertising pencils and that a shoebox full of them marked two dollars made perfect sense? The horror. The Donna of it all.

The doors opened and the first fifteen were admitted, handing over their tickets and entering the house like a greedy pack of dogs. Jane heard a man's voice behind her, angry about the number system. She turned to look at the source.

"Nine o‘clock the paper says and nine o'clock we're here. What's the deal? Who you gotta … ?" Jane turned around and tuned out the voice. Another new guy, Jane thought, Where do they come from? Aren't there enough dealers and pickers now? Can't we just dose the tunnel and say, Sorry, full up?

Jane paused in the small tiled entry and tried to take in everything at once. The living room on her right held the tables with plates, glasses, stemware, and some pottery figures. A case next to the all-business card table with calculator and newspapers for wrapping the more fragile objects held finer jewelry, pocket knives, and small artifacts of eighty years on earth, sixty years in one house. Hat pins, tape measures in Bakelite cases that advertised insurance companies, their four-digit phone numbers recalling a time when one phone line was all anyone ever needed and the possibility of running out of numbers, creating new exchanges and area codes, would have been a joke pulled from a bad science fiction novel. Inside the case were several sterling silver thimbles, which gave Jane hope that there would be buttons. A seamstress hoarded buttons and rickrack and old zippers, tucked them away into basement drawers, and stuffed plastic bags full of them into guestroom closets. That Coates and Clarke seam binding might be right around the bend. In the corner of the cabinet were three gold initial pins from the 1940s. Jane stretched to read them, then realized she would not have to make up a name and fit it to the initials, "RN." A nurse, Jane thought. Perfect. Clean, well organized, good linens.

All this information and conjecture took no more than five to seven seconds to gather, while Jane got the lay of the land from the tiny foyer. She shook herself out of her reverie on the houses owner and took off in search of stuff.

The kitchen. Jane grabbed a seven-inch Texasware pink-marbled plastic bowl from a box under the table and held it up to the worker standing at attention, pencil in one hand, receipt book in the other. "Fifty cents?" she answered to Jane's wordless question. Jane nodded, and the woman scribbled it down, starting Jane's tab.

Jane filled the bowl with a Bakelite-handled bottle opener, a wooden-handled ice pick, and four small advertising calendars illustrated with watercolors of dogs. The calendars were from the twenties and the picture, POODLE WITH BOBBED HAIR, touched Jane's heart. They were also in perfect condition, taken from a kitchen drawer filled with Chicago city street guides from the thirties and forties, old phone directories, worn address books, some stray S&H Green stamps. Jane's heart filled with appreciation and desire as she realized just how much and how carefully this woman had saved.

Before she left the kitchen, Jane snatched up the oversized oak recipe file. She collected the wooden boxes sized for 3 × 5 cards, sorting buttons and gumball machine charms into them, but this box was more than twice that size and it was overflowing with handwritten cards, yellowing newspaper clippings, and stained cardboard recipes that had been cut from Jell-O and cracker and cereal boxes.

"Six?" asked the worker, barely looking up.

Jane thought the tag on the box said ten, but it was hard to see, and she didn't have two free hands to fiddle with it, so she nodded. Six was probably too much, but if the tag said ten, it was a bargain, wasn't it? The kitchen was so satisfying, filled with the kind of well-maintained but used and loved vintage items that spoke so convincingly to Jane's soul. Take me home, they all said, loud and clear. At least that's what Jane thought she heard them say as she hustled through the kitchen. A souvenir of Florida spoon rest, hand-crocheted pot holders, tiled trivets that some child had labored over in the crafts room of summer camp. An ice crusher! Not an Ice-O-Matic, though, and Jane never cheated on the Lucky Five.

This was a forties to fifties household where the mother probably stayed home with the kids, baked cookies, and packed healthy sack lunches. Jane's thoughts lingered on the sack lunches, remembering back to elementary school meals in Saint Patrick's Grade School cafeteria. The food had been unrecognizable and inedible. She'd begged her mother to allow her to bring lunch, but Nellie, ever the practical woman and only occasionally the empathetic mom, had been thrilled with the modern addition of a cafeteria where students could buy a hot lunch. Nellie would no longer have to slather peanut butter and jelly on Wonder bread and wrap up chips and fruit every night.

Realizing she could skim off one more chore from her already too filled night of housework after nine hours work at the EZ Way Inn, Nellie refused to listen to the complaints about slimy macaroni slathered in ketchup, unrecognizable chunks of meat in a gluey gravy over slippery instant mashed potatoes. Not wanting to waste time with the lengthy explanation of how tired she was at the end of a long day of cooking, serving, and tending bar, Nellie didn't bother to explain the reasoning behind her decision.

"Eat the hot lunch … it won't kill you," she'd said.

"My mom thinks it's more nutritious for me," Jane had said, stirring a mysterious mix of meat and rice, explaining to her friends who occasionally shared a cookie or orange segment with her from their own brown bags.

Jane, forgetting all about lunches, brown bag or otherwise, hummed as she walked carefully down to the basement, ducking her head and stowing her finds into a large plastic totebag that she carried with her to all sales. Thoughts of Nellie might have sneaked into the kitchen with her, but Jane refused to take her along as she continued through the house. Donna was still going through kitchen cupboards, and although Jane feared her rival would be the one to find the blue Pyrex mixing bowl that would complete the set that sat waiting in Jane's basement, she knew it was pointless to stand behind Donna and watch her. Better to strike off in a new direction. Better to sniff around in the basement.

She noted that her assessment of the owner, a nurse, had been correct. Objects did seem clean and well packed, neatly organized on crude, built-in shelves in all four of the spotless basement rooms. There was a little storage area off the laundry room that looked dusty and promising for boxes of unsorted odd dishes and holiday decorations, but Jane decided to scan the shelves left to right, top to bottom in each of the rooms first.

She moved off to her right and found herself in the middle of First Aid Central. Boxes and boxes of gauze bandages, sealed bottles of disinfectant and saline solutions, rolls of tape were stacked floor to ceiling. Two women, neighbors or friends from the sound of their conversation, were already in there, one of them cramming rolls of paper tape into a wicker shopping basket.

"Couldn't take it back legally, even if it was sealed. She said a lot of the patients and families just told her to get it out of their houses and donate it somewhere," said the one collecting the tape. "Mary said she was going to send it through the church to some places where they'd take anything, you know, any kind of medical supplies."

"Was the owner a visiting nurse?" asked Jane, breaking two of her rules—asking a question and getting distracted by the owner's history instead of the owner's stuff.

Both women looked at Jane, not surprised at all that someone might want to chat during the feeding frenzy of a house sale. Yes, they were Mary's friends and neighbors, amateurs, not dealers or professionals.

"No, not Mary. She was a nurse a long time ago, but it's her granddaughter who's a visiting nurse, gets these supplies. Mary just wanted them not to go to waste."

Jane nodded, enjoying the contact with Mary through these two old friends.

"Mary saved all of everybody's things. Her husband's stuff is in that other room, and he's been dead for nearly thirty years."

Jane tried to keep an appropriately sympathetic expression—after all, Mary's husband had been dead for thirty years—and not show the callous joy she felt when she pictured some of the vintage clothes and office supplies that might be in the adjoining room.

"Was Mary's husband a doctor?" asked Jane, spotting and seizing a buttery leather doctor's bag on the floor.

Both women laughed and the one who seemed to be in charge of talking for the pair said, "Oh no, dear. Bateman owned the Shangri-La."

When Jane shook her head and shrugged, the silent partner whispered, "It was a tavern. Bateman was a saloon keeper."

Jane hoped the women didn't think her rude, but she turned away almost immediately. She couldn't move quickly enough into the "Bateman" corner of the basement. A saloon keeper! Eureka! Pay dirt! Gold in them that hills. If she had the flexibility of an animated cartoon character, she would have kicked up her heels and leapt into the next room. She sighed with pure rapture when she saw the similarly organized and shelved remnants of thirty years in the tavern business, all of it clean, boxed, folded, and tagged.

Jane wiped the corners of her mouth with her sleeve, just in case she had inadvertently drooled.

Don and Nellie, Jane's parents, had operated the EZ Way Inn in Kankakee for forty years. A ramshackle building across from the now-dosed stove factory that had given the town so much employment, so much prosperity, the EZ Way Inn was as charming on the inside as it was tacky on the outside. Don had never been able to talk Gustavus Duncan, the owner, into selling the building.

For forty years, Don had paid rent on the flimsy shack, shoring up and improving the interior, praying that a heavy wind wouldn't blow it all into kindling overnight. Don always called himself a "saloon keeper," considering that to be the most honest description of what he did. He never gave up though. Each first of the month, along with his rent check, he extended the offer to buy. Four hundred and eighty offers finally worked their magic. Last month Gus Duncan had finally caved.

Don had called her, his deep voice trembling with excitement.

"I'm buying the place, honey,' he said. "I guess now that the factory's been closed for twenty-five years, old Gus decided nobody's going to give a million to mow down the EZ Way and make it into a parking lot."

Jane hadn't asked if it was still a worthwhile investment since her father had lately talked about retiring at least once a week. She didn't want to do anything that would temper his excitement about this deal, this sale that would give him so much joy. She would leave that up to her mother, Nellie, who had been throwing cold water on Don's plans for thirty years.

"Now I'll be a tavern owner instead of a saloon keeper."

"Pay raise?" Jane asked.

"Pay cut, but I get a bigger office," Don said, describing the building improvements he was planning.

The improvements were scaled down considerably when Don realized that no credible carpenter would guarantee that the building wouldn't collapse if they tried to break out a wall or extend the roofline. Every contractor who had ever sipped a Miller sitting at the big oak bar inside the EZ Way told Don the same thing.

"Doctor up the bathroom plumbing and bring the electrical into the twentieth century, mid-twentieth century. Don't even consider the twenty-first. Any bigger improvements might prove disastrous."

"Hell, Don, I believe my electric drill could knock a wall down," said Eugene Smalley, a customer and cabinet maker. "Let's put in some bigger windows and add some lights so a guy can see if he has trump when he's playing euchre and leave it at that."

Nellie had told Jane last week that the carpentry was done and they were planning on having a grand opening next month.

"After forty years in this place, your dad's acting like a teenager with a new car," Nellie had said.

When Jane asked how it looked with bigger windows and improved lighting and bathrooms, her mother had snorted.

"All the better to see the dirt and dust with. We was better off when it was dark so you couldn't see where the walls don't quite meet or the cracks in the ceiling."

"Is Dad going to paint and redecorate?"

"Has to. Plaster cracked all over the place when they did the windows. I haven't been able to make a pot of soup in a month because of the dust."

By next week, the painting and plastering and pounding would be finished, and Don had promised Jane that she could come in and decorate. That is, she could decide where the beer distributor's big calendar and the bulletin boards where Don posted the golf league standings and the bowling league scores would hang.

"Same place, if you ask me," said Nellie during their "conference call," which meant Nellie was listening in on the bedroom extension while Don called Jane from the kitchen.

Jane had been planning some surprises though. She had found some great vintage signs, old beer advertising trays that could be hung, even an old high school trophy case that she figured could stand in the corner f

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...