- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

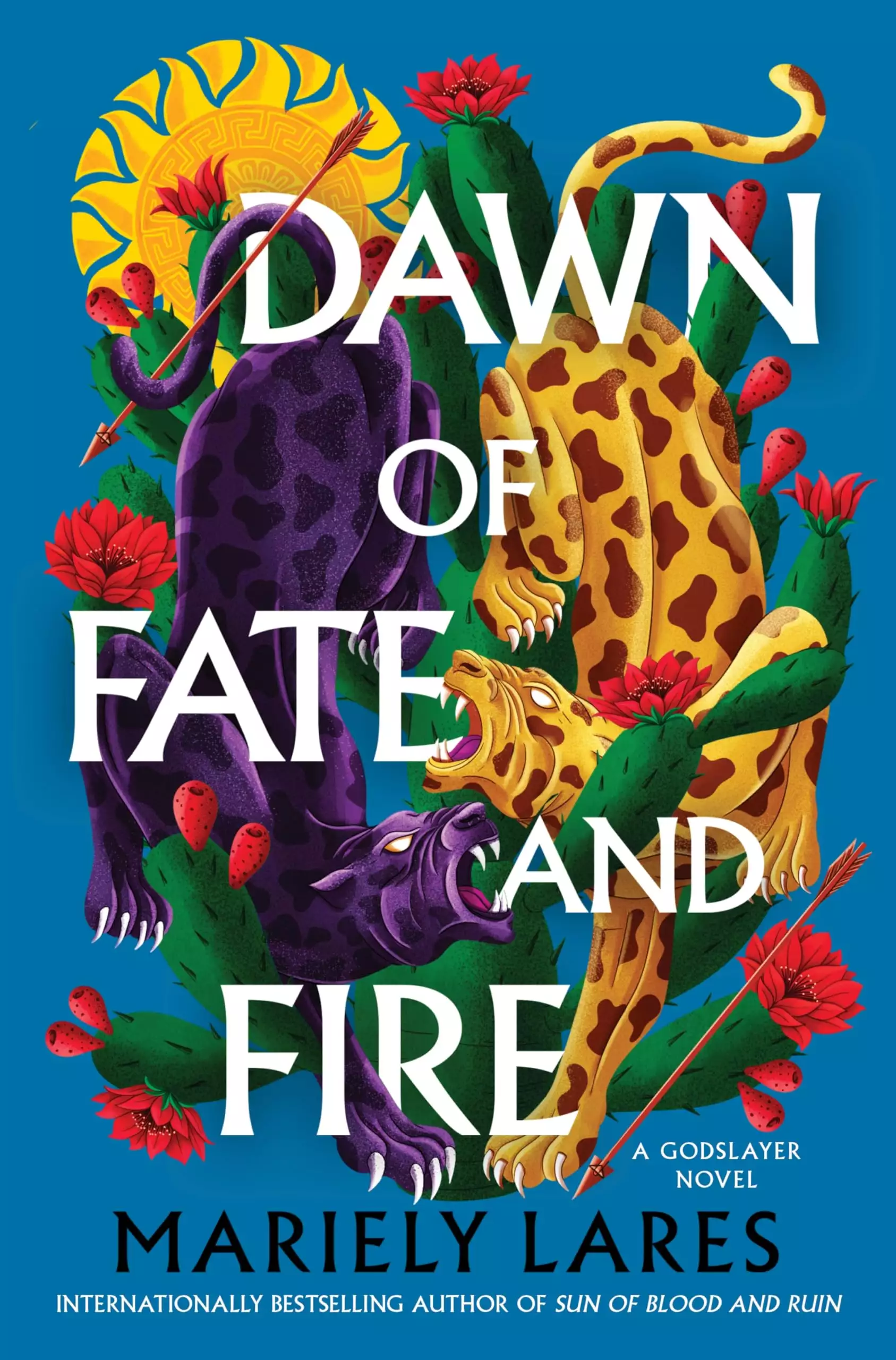

The stunning conclusion to the duology that began with the internationally bestselling Sun of Blood and Ruin, this Zorro reimagining weaves Mesoamerican mythology and sixteenth-century Mexican history into a swashbuckling historical fantasy filled with magic, intrigue, treachery, and romance.

They call her many things. Witch, Nagual Warrior, lady, Pantera. And after defeating the Obsidian Butterfly, Leonora carries a new title: Godslayer.

Peace in Mexico City is fragile. Rebellion brews in the North, and when the people’s safety is at risk, Pantera must once again become the demure viceregent Leonora to stop a war before it begins. But her friends are scattered, Tezca is gone, and one wrong move could seal her fate. Caution is her ally, for the real Prince of Asturias—her former betrothed—has arrived at court, reigniting rumors that Leonora and Pantera are one.

A greater threat looms in the mountains, where a false king seeks to summon the god of night using a weapon of untold power. It’s up to the Godslayer to confront this enemy. . . and the one growing within her. Only by embracing her divine origins can Leonora triumph over the forces of darkness—and maybe even spark a revolution that could change Mexico’s fate forever.

But in doing so, she risks losing herself forever.

Release date: August 12, 2025

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dawn of Fate and Fire

Mariely Lares

The battlefield is the place,

where one toasts the divine liquor in war,

where are stained red the divine eagles,

where the jaguars howl,

where all kinds of precious stones rain from ornaments,

where wave headdresses rich with fine plumes,

where princes are smashed to bits.

Nezahualcoyotl, King of Texcoco

For everything there’s a season; there’s a time for sowing and a time for harvest, a time for toil and a time for rest, a time for living and a time for dying.

Tonalco, the dry season, is a time for war.

The gods Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli together command the natural cycle of the year and the changing days. Before the Spaniards came, two shrines topped the Great Temple in the center of Tenochtitlan. Tlaloc’s faced north, the god of rain bringing fertility to the earth. The other toward the south for Huitzilopochtli, the god of war who scorches the land with battle.

The seasons reveal a proper time for all things to happen. The solar calendar with its eighteen months of twenty days. Each celebrates a festival honoring a different god.

In the hunting season of Quecholli, a great feast honors the god of the chase, Mixcoatl. Other months are dedicated to Tlaloc, such as Tozoztontli. Under the old ways, pipiltin, the nobility, queens of Nahua cities, kings of kings, journeyed to the summit of Mount Tlaloc to offer prayers and sacrifice, ensuring the rains would come again.

As far as any can tell, the last Tozoztontli was performed successfully.

As far as I can tell, that must’ve been a long time ago.

Now, the air scorches, the land parches.

Tlaloc may be the god of rain, but even he can’t manage all the watering alone. That’s why his little assistants, the Tlaloque, carry immense clay pots to fill and, when Tlaloc tells them, they break those vessels all over the land, lakes, and seas.

However, they have done no such thing in months.

In the dry season, hiding is not easy. Catching prey, less so. Though I have black spots—all jaguars do—the rest of my fur is also dark. I don’t blend in with my surroundings.

Stay quiet. Stay out of sight. Those nosy howlers in the treetops will alert the entire forest that I’m on the hunt. They can see me coming a far distance away. The oldest and largest of the troop, one bearded male with thick and full hair, is the leader. He’s the worst of them.

I am not larger than the bull, bigger than the bear, heavier than the whale, not as clever as the snake, but here the jaguar reigns supreme, and when I show up, the howlers sound the alarm.

Tonatiuh bright in the sky is my ally, creating shadows. The ideal cover. I keep to the shade as I pad along, careful, listening for movement. Within me, a deep pit of hunger festers. It’s been days, weeks, of eating scraps. The natural does not always come naturally. Despite not having enemies, except perhaps the raucous monkeys, I have had to learn how to live in the forest, how to survive.

The backwaters, hidden in the heart of chaneque territory, offer some relief. This part of the river holds water year-round, even during the dry season.

No screeching calls. All is going well so far.

Silently, I swim in, my senses attuned to every ripple and current, looking for sunshiny creatures. I’m not a fussy eater. Anything

along the river, or in the river, will do.

On the bank, two blue-green pits glint like jewels. A caiman’s nostrils, followed by the whole snout. It lies motionless, cloaked in mud. Perfect camouflage.

A shiver of elation starts in my paws, races up my legs, and quivers through my body. Nothing is more exciting than that first glimpse of your prey. The caiman is magnificent—about my size, its craggy skin spotted almost like mine. Here we are together, bound as one in this wonderful moment of life and death. My heart starts racing.

I paddle in the water with practiced silence, eyes locked on my target. Every muscle in my body is taut with focus as I choose my angle of attack.

Just a little closer.

One bite is all it takes. Then the monkeys can howl all they want.

Closer.

Closer.

Now.

I pounce.

My jaws snap shut, piercing the soft underbelly of the neck, where the scales are thinner. The caiman wriggles—a desperate attempt to escape. But in less than a heartbeat, its struggle ceases. I start pulling it to the tree line, and the howlers start their screaming chorus, harsh and savage.

Too late, my friends.

Death in the forest is quick.

We predators can afford no mercy.

The howlers continue their ungodly alarm, but their song almost immediately dies away. They will sing again, of course, in an hour or two, but from a different place, for the monkeys must always travel between songs. Otherwise, it would be an easy matter for enemies to find them among the branches.

The clawing hunger finally subsides as I feast on the caiman’s entrails. My belly swells with its flesh; delicious meat, my snout splattered with hot sweet blood.

I swivel my ears. A rustle of leaves behind me betrays a presence, though it was their scent I caught first from a distance.

My fur rises on end, tail twitching furiously. Then, baring my bloody fangs, I let out a growl, a threat, a promise of pain. I tighten my

muscles, bend my hind legs, and just as I am about to leap, a pushing pressure inside forces my form to change.

I don’t remember the last time I was human.

I’m curled up on the forest floor, my skin bare against the dead leaves and twigs. Everything hurts. My muscles are like knotted ropes, my limbs a pair of willowing reeds. I cough, spitting out bits of flesh and guts stuck between my teeth. The more I move, the more my body aches. I struggle like an insect caught in a spider’s web. I try to push myself from the ground and find that I’m covered in blood. I turn and vomit, again and again, until I think my ribs will crack, and I cannot bring up anything more. I’m completely empty.

Everything is bright and loud and spinning. My eyes are heavy, my head dull, disoriented. Changing forms is worse than waking up from a drunken binge. I am aware of myself, but I have no control. I wonder if this is what babes feel when they enter the world. I blink, once, twice, and then again before shaking my head, trying to clear the mist in front of my eyes. Dazedly I try to make sense of what just took place. I didn’t start the shift. It was spontaneous, like sneezing.

This isn’t the first time it’s happened. Many times before, the Panther has urged the shift, as if my skin will split open if I don’t. But never have I involuntarily reverted to my human form. What went wrong?

I’m looking at my answer now. It takes my mind a second to recognize that distinctive chaneque smell.

“You.” I orient myself to uttering words again. “You did this to me.”

Zyanya stands over me, all three feet of her, face petulant. She’s grown a shock of white hair, exposing pointy ears. A brown mantle makes her short body look longer than it truly is. Talons allow her bare feet to cling to trees and move easily through the rough terrain.

“Aren’t you going to say anything?” I ask.

“I’m waiting,” she says.

“Waiting for what?”

mal.”

My stomach cramps again. Clutching it, I hack up a fist-sized, soggy clump of undigested fur.

Zyanya sighs. “You did this to yourself. I warned you not to abuse your power. Staying in your nagual for too long has consequences. It’s dangerous not to be able to shift on command. If you lose focus, you’ll find yourself somewhere in between, stranded, with no tonalli to help you complete the change. Is that your wish?”

I wipe my mouth with the back of my hand.

“You can’t live in chaneque territory forever, Pantera,” Zyanya says.

“And where should I go?” I snap. “Neza is dead. Snake Mountain has fallen. Ichcatzin would sooner kill me than allow me to live in his midst. My brother would burn me at the stake the moment I set foot in the capital. I am not wanted anywhere.”

Her bright yellow eyes, large and rounded, soften. She shakes her head as if pitying a fool.

“I’ve protected you, have I not?” I ask her. “From the dangers in the forest.”

“Yes, but not from yourself. You are welcome here, but you are a guest. And guests show respect. Guests have manners.”

She looks behind me, where the caiman carcass lies partly eaten.

“We make use of the forest,” she says, “but we take care of it. You’ll have to make a new home for yourself. Elsewhere.”

I’m reminded that though I’ve befriended the belligerent chaneques, the little creatures are protectors of the forest. Upon intrusion, they will throw stones, pull hair, weave disorienting illusions. Frighten by any means at their disposal. Some have power over nature. Once spooked, a person’s tonalli will come flying out of their body, at which point the chaneque will steal it. And, as I all too well know, without tonalli, you die.

“What will you have me do, Zyanya?” I say defeatedly. “Beg to Ichcatzin? I will not beg.”

Before Zyanya can answer, the wind whispers against the strands of my hair, a susurrus of sound. Voices . . . noises that seem to come all at once and wrap around me.

I turn around slowly, listening to every sound in the distance.

“What is it?” Zyanya asks.

A deep growl escapes my throat. “Your friends are doing this. Make them stop.”

It’s a cacophony, each sound inside the other, all competing to be heard—wild laughter, mosquitoes buzzing, the tread of many feet, the flight of an eagle, the rushing water crashing against the rocks, the angry call of howlers and chachalacas and a hundred other animals. A deafening tempest.

“Make them stop.” I raise my hands to my ears. “Stop it. Stop it!”

Zyanya rushes to me and takes my hands. “Listen to me. Breathe. Shut it out. You know how to do it. Focus. Do you hear me? Focus only on my voice.”

Her words are far away. A great pain goes through my head, and I cry out, “Quiet!” The ground trembles as a destructive force of tonalli frees itself out of me, flying in all directions. It picks up Zyanya like she is nothing, tossing her across the clearing, and everything else with it.

Trees strain against the onslaught as tonalli continues to burst from me, unrestrained and unyielding. I fall to my knees. I can’t make it stop.

I squint my eyes to keep out the violent dust, but amid the eddying debris, I make out Zyanya held against a tree. She struggles to lift a hand, curling fingers at me, and to mouth words.

The devastation finally dies as my vital force is taken from the crown of my head.

I awaken, swaying. My head is in a dizzying spiral. As I sit up, stifling a groan, I realize I’m dangling in a hammock strung in the corner of Zyanya’s hut. I grip its edges and try to free myself, squirming like a worm. One of my legs is caught in the rope, and the hammock swings violently. I roll around, drop, and hit the earthen floor with a loud thud.

“The legendary Pantera.” Zyanya shakes her head.

Her hut has a reed bed padded with feathers, chairs, tables, and a cooking area, where Zyanya sits crushing herbs in a molcajete. It’s quiet, too quiet. I don’t hear much of anything. How can I? She took my tonalli.

Clumsily, I sit on a chair too small for me. “I didn’t mean—I’m sorry. That’s never happened before. Well, not like that.”

e glints with my vital force in an intriguing swirl. “I can feel it. And the proof of that is evident,” she says, eyeing my hair. It’s been a long time since I’ve seen my reflection, but

as my fingers brush through the strands, I realize it now falls well below my waist.

“What do you mean growing?” I ask.

“Learning,” she says. “Responding to the demands you make upon it.”

“How can that be?”

“You’re the daughter of the Feathered Serpent.” I’ve spoken of this with no one, and Zyanya must see the look of surprise on my face because she explains, “Your tonalli told me.”

I frown. “Told you?”

“The gods manifest their power in circling motions,” she says as if that makes any sense. “You’re not human, Pantera. Not entirely. What you did that night when the Tzitzimime came . . . it was one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen.”

I hardly recall my past human life. After months of living as the Panther, the mind stops thinking like a human. Every sorcerer knows: stay in your nagual for too long, you risk losing touch with reality or getting trapped as an animal forever.

I shrug. “If you say so.”

“There’s no denying you’re a sorceress. This is what you trained for. But you have god tonalli. You must learn to center your vital force inside, where it can be held and harnessed. With increased tonalli, the path becomes more slippery. Order cannot exist without chaos and chaos cannot exist without order. There must be balance in this world, and within you. Until then, you are dangerous. To yourself . . . and others.”

Leonora . . . A male voice comes from a distance.

“No, no, no. Not again,” I say frantically, shooting up from the chair. “It’s not possible. I don’t have my tonalli. I can’t be hearing things!”

Zyanya turns her head. I sag with relief; she heard the voice too.

Someone is calling me, and for a moment, I don’t realize it’s my name. Then my human mind clears, and at once, I think, Leonora? Why Leonora?

The name sounds too odd, too unfamiliar to my ears. Pantera would have been so much better. After all, it is his voice.

I haven’t heard his voice in what seems like years. Since the victory at Snake Mountain, where we fought the Spaniards and the Tzitzimime, and won. He made a great slaughter, and I, too, did my part. At the battle’s end, I faced the Obsidian Butterfly, and the Sword of Integrity sent her to the blackness of the heavens. After, we lay together on the hillside, watching Tonatiuh rise, and we ran as fast as our paws could take us. Then, he returned to his people, the Tlahuica, and I went my way.

What I should have done, what my heart told me to do, was give him the truth of who he is—a god. It’s a secret unknown to himself, revealed to me by his mother, the Precious Flower, Xochiquetzal. I should have told him about my true father, Quetzalcoatl, and my mother, Tlazohtzin, the woman who, through my birth, became a goddess and a servant of the Obsidian Butterfly.

I should have gone with him. He asked me to. Instead, I remained in chaneque territory with Zyanya.

I have not seen Tezca since that day.

He calls my name again. I go to look for him, following his voice.

My human legs have not been used in a long time, and they feel unnatural; I can barely get my knees to bend. I stumble forward, no longer able to stand erect. Unsteadily, I brush the dirt from my knees and push myself back up.

The forest isn’t kind to bare feet, but I pick up speed, leaping over fallen trees, pushing through bushes. More in control. More like myself. I reach a mossy clearing. It undulates, the vegetation floating atop water that bubbles beneath.

“Pantera, wait!” Zyanya trails behind me. “Stop!”

I’m ready to leap, but she grabs my shoulders and pulls me back. We teeter on the spongy edge for a moment, about to fall together.

“Look.” Zyanya points.

His voice calls to me again.

It’s not Tezca. It is Rayo, the ahuizotl, mimicking his speech. He’s a terrifying creature, a tricky one too. He has the ability to imitate sounds and voices, using them to lure victims near so he can snatch them with his sinuous tail claw.

Amalia and Eréndira jump off the ahuizotl, and Amalia tosses the flesh of a dead animal toward the eager Rayo, who surges to catch it in the air, then plunges back into the water.

Eréndira greets me with a nod. “Still alive, Pantera?”

“Still alive, princess.”

“Good. I’m glad. I didn’t think we’d find you.”

“I told you she would find us,” Amalia says, pleased. “It’s good to see you, Leonora.” She opens her arms, coming for an embrace. Her golden hair is braided, and she’s dressed in a simple blouse and pants. The most ornate thing about her is the beaded cross encircling her neck.

“You are changed,” I tell her.

“You are not,” she says with a chuckle. “When was the last time you washed? You reek of death.”

I grin. “The forest becomes you.”

“Yes,” she says, looking up at the trees. “It’s been a good place for me to grow. I would not have done so with my mother’s coddling.”

“It’ll be dark soon,” Zyanya warns. “We should return to Tozi.”

If you ask a chaneque, they will say: chaneques don’t live in the forest; chaneques are the forest, as much as the trees, plants, and animals. They’re constantly moving, like the forest. When not frightening intruders and stealing tonalli, they gather in different communities of between twenty and thirty, foraging, hunting, and building their homes which, for a wandering group of little creatures, is an interminable process. Chaneques have been known to set up their huts in a couple of hours, but they are constantly adding rooms, repairing doors, strawing and re-strawing the roofs. Sometimes, for reasons I have yet to understand, they will take down their huts and begin again.

If there’s one thing chaneques hate more than intruders, it’s being thought of as children. They might look like children, but they’re not. They’re not even human—not anymore.

We pass several round bamboo huts lined up one next to the other, some clustered in small areas, a few standing alone like tiny islands.

Such is the village of Tozi.

The chaneques flock about us, and soon, Amalia has a crowd around her. They tug on her hair and push her sleeves up so they can examine her skin more closely. They spit on her freckled forearms and rub, wrinkling their noses in disgust when her freckles don’t come off. Other chaneques are fascinated with her pockmarked face, thinking Amalia is a great warrior. They’re not wrong. She battled and conquered the pox.

The eldest in the community, twenty-six, a very respectable age for a chaneque, introduces himself to Amalia and Eréndira as Itzmin. He’s no taller than my shoulder, but he expresses himself confidently, recognized as the leading authority by all the chaneques in Tozi. Though his face is considerably lined, Itzmin still possesses the glow of a child’s countenance, keen yellow eyes, floppy ears, and sparse, white hair.

“Niltze,” Amalia greets. “Notoca Amalia.” She’s been learning Nahuatl from Eréndira. It’s far from perfect, but it’s sufficient to make herself understood.

“I am Eréndira,” she says, taking a step forward. “We have come to—”

“We know, Owl Witch,” says Itzmin. “We’ve

been expecting you.”

To chaneques, dreams are a different form of reality. They begin each day with a ceremony where they share their dreams from the previous night, from the youngest member to the eldest, and based on those dreams, the village decides what they will do that day. Sometimes the dreams are so long, they dictate full months.

They must have dreamt of Eréndira and Amalia’s arrival.

Eréndira and Amalia trade perplexed glances but simply nod their gratefulness.

“You come to Tozi,” Itzmin says. “Good. Rest your worries. You’re safe. We dance and drink tonight.”

Amalia arches an eyebrow. “Aren’t they a little too young to drink?”

Though Amalia murmurs this to me, barely above a whisper, her question is met with a resounding silence and glares. Chaneques have flawless hearing, perhaps even more than I do. With their flopping ears moving to and fro, they can discern the slightest sound.

Itzmin narrows his eyes. “Settle in. Zyanya will show you where,” he says with some asperity, before he walks away.

“What did I say?” Amalia asks innocently.

“You were doing so well,” Zyanya says, humor lacing her tone. She gives Amalia a playful pat on the back. “Come, countess.”

A look of displeasure flits across Amalia’s face. Eréndira chuckles.

“What did I say?” Zyanya taunts.

“Don’t call me that,” Amalia protests, though her voice lacks any real heat.

“Call you what? Countess?”

“It’s not who I am anymore.”

“Sorry, countess,” Zyanya says, her lips curved upward. “Whatever you say, countess.”

Still smiling, Zyanya heads toward her hut, and Amalia exhales sharply.

“She’s just teasing you,” I assure.

“Why?”

“I’m not sure,” I say, thinking of the many times I’ve been the recipient of Zyanya’s jests. “I think she gets pleasure from it. It’s harmless. Well, most of the time. Unless you remind her of her age. She doesn’t like that.

None of them do.”

Metzli, the Lady of the Night, has not yet risen when the chaneques start gathering in a circle. Musicians pick up their instruments and immediately the village comes alive. Every chaneque takes part, bursting into a bright and merry song, clapping their hands and shaking the rattles on their feet.

There is music, then there is chaneque music.

The sound is extraordinary, a very full and rich form of singing, accompanied by the mesmerizing sounds of the drum, the conch, the flute, the whistle, the horn, all wonderfully blended into the melody.

Long ago, when the earth was a quiet and joyless place, Tezcatlipoca gave humans the gift of music.

It was an agreement between Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl. In the dawn of the Fifth Sun, the Thirteen Heavens were filled with music. Although humans had lush vegetation, flowers of all colors, and much beauty to behold, Tezcatlipoca noticed they weren’t truly happy. And Quetzalcoatl wished for his people to have all the riches of life, so Tezcatlipoca, with his help, awakened the world. For the first time, people sang, and so did the trees and birds, whales, crickets, and frogs. Ever since, music has filled our souls.

The moon now illuminates the sky as it climbs above the trees. The song drifts into the night, melting into the sounds of the forest.

“Well?” I say, offering Amalia a cup of pulque.

She takes the drink and sips it, licking her lips afterward. “Well, what?”

“Are you going to tell me why you have come?”

“What if I said I simply wished to see you?”

“I would say you’re lying.”

Amalia drinks, hiding a smirk.

Eréndira approaches us, her expression grave.

“What is it?” I ask.

“We’ve come because of Ichcatzin,” Eréndira answers. “He rules Snake Mountain with an iron hand. He has some kind of plan to restore Mexico to its former glory. Chipahua has been made high general. He plays along for now, but Ichcatzin doesn’t trust him. He knows Chipahua is loyal to Neza.”

, though this he never admitted. A brave man, a good and just man. He believed in a better life for his people with rights and privileges, where all persons live in harmony and with equal opportunities. It was an ideal he hoped to live for and achieve, and he was prepared to die for it. But a lesser man,

his own brother, Ichcatzin, drove a sword into his back. I wept

for his death.

“Chipahua is working to find out Ichcatzin’s plan without arousing suspicion,” Eréndira continues. “He has a few allies. Most are too afraid to openly oppose Ichcatzin. But when Ichcatzin falls—and he will fall—Chipahua shall take his place.”

Chipahua, a king? As a Shorn One, his duty is to the battlefield, not to lead. Yet, he is Neza’s cousin, a nobleman, and he has the strength and wisdom needed to guide Snake Mountain.

“Ichcatzin’s plan—you think it involves shedding blood?” I know the answer before I ask the question.

Eréndira nods somberly. “Ichcatzin didn’t just murder Neza to seize power. He isn’t just some false king on the throne. He has a larger plan, Chipahua is convinced. I think we should find out what he’s up to.” A bitter breath. “This should never have happened. I wasn’t paying attention. If only Neza—”

“Neza’s death wasn’t your fault,” Amalia reassures her. “Ichcatzin is to blame.”

For a moment, Eréndira seems to fade, trapped in her memories and emotions. She is not usually lost for words. She looks tired, a different kind of tired. An angry kind of tired.

I drink my pulque, watching Zyanya dancing with the other chaneques. “What will you do?”

“Fight,” Eréndira says without hesitation. “Fight like I always do. For Neza. His death will not be in vain.”

Amalia huffs as if the world is giving her a headache. “Aren’t you forgetting something? Tell her, Eréndira. Tell her the other reason why we’re here.”

“Quit telling me what to do,” Eréndira moans.

Amalia crosses her arms. “Quit acting like you need to be told! You’re always saying how Snake Mountain is a people, not a city. What is the point of taking back the city if we don’t have a people?”

Eréndira makes an effort to collect herself. “We’re dying,” she confesses finally. “We’re dying of the white demon’s disease. Our remedies cannot cure it. The tribes are scattered. Our great warriors are gone. We need a place to heal. To stay alive, away from Ichcatzin’s wrath. And after, to rise again, and avenge what has been lost.”

“I know what this disease is, and I know how to treat it,” says Amalia. “I myself have been cured of it. I know how to help. There is medicine in the capital to manage the symptoms.”

She means the palace.

She wants me to go to Jerónimo.

“I’m sorry. I can’t go back,” I say hoarsely.

“What? Why not?” Amalia asks.

“Jerónimo knows I am Pantera,” I tell her. “He made it clear he never wanted to see me again.”

“Leonora, please,” Amalia says. “You have to try. We can’t watch helplessly while the plague rages and people continue to die. You’re the viceregent of New Spain.”

“I doubt it,” I say. “I’ve been gone too long.”

“Jerónimo listens to you. He doesn’t listen to me. He takes your advice.”

“Except when he remembers who I am, or he

is angry about something, or when things are going badly, or I don’t go to Mass, then he does not.” I look at Eréndira. “He will give you an audience. After the battle with the Tzitzimime, Jerónimo made his promise to work with La Justicia.”

“Neza is dead,” Eréndira snaps. “So is La Justicia.” Her hands fist at her sides, fingers pressing into her palms as if that might somehow keep her grief at bay.

“The promise didn’t die with Neza. You shook hands with my brother,” I remind her. “Neza’s beliefs live in you, in me, in everyone who stood beside him. We are all La Justicia. One face. One voice. La Justicia is alive within us.”

Eréndira glares at me, struggling between the pain of anger and loss. “My people need me,” she argues. “I can’t leave them. We’ve tried to contain it, but it spreads quickly. We travel at night, and we carry the sick on litters. Those who can still walk take turns carrying those who can’t. When we stop, we dig pits to burn the clothing, keep the children far from the sick. Even with every precaution, the pox keeps claiming more of us. We can’t go on like this forever, Leonora. We’re camped not far from here, but if Ichcatzin finds us, he won’t let us escape. Snake Mountain isn’t safe. We can’t make the long trip to the capital.” She pauses, her breath unsteady. “We have nowhere to go.”

In that, we share the same struggle.

“You heard Itzmin,” I say. “There’s room for everyone, and chaneques aren’t vulnerable; they don’t succumb to the pox.”

Amalia shakes her head in disbelief. “You will not help?”

I sigh. “It’s complicated, Amalia. There are things you don’t know and wouldn’t understand.”

“Like what? Why don’t you explain them to me?”

She waits for an answer. It doesn’t come.

The dancing begins to wind down late into the night. Soon after, the chaneques withdraw to sleep, and Zyanya finds me brooding inside her hut. She carries my mask, my attire, my dagger, my belt, and the Sword of Integrity, which is nearly her length, and she has to drag it about. This tells me she knows what has been asked of me—either because Amalia or Eréndira told her, or because the trees did.

Zyanya drops all my belongings at my feet. My eyes glaze as I close a hand around the blade’s hilt. It’s been a while since I’ve held her.

“I’m not going back to the capital,” I say.

She exhales one deep breath from the exertion. “Then don’t.”

I give her a puzzled look. “My power is growing. I must be careful. Isn’t that what you told me?”

“Yes.”

“Nine Hells, Zyanya, just say what you want to say and be done with it.”

She comes closer and sniffs the air. “Amalia was

right. You do smell. Your stench is invading my senses.”

I only barely stop myself from rolling my eyes. “Is it wise to return to the palace while my tonalli swells unrestrained within me?”

“No.”

“Then why advise me to leave, if I’m so unstable?”

She considers this, fondling the green stone on her belt with my vital force.

“You wish to restrain my tonalli?” I ask when she doesn’t answer. “Keep it under control? Is that it?”

“No, not restrain it,” she answers. “Protect it.”

“From what?” I nearly shout.

“From those who might try to take it for their own benefit. I have a responsibility to maintain the—”

“The balance. Yes, yes, I know. And what about me?” I say irritably. “Without my tonalli, I’m vulnerable.”

“With it, you’re dangerous.”

“I’d rather be the predator than the prey.”

“Yes, it’s your nature.”

“Zyanya,” I say, “I have known the loss of tonalli. I would begin to deteriorate, forget. I could get lost, not knowing what to do next.”

“Oh, yes, I agree,” she says idly as if we’re chatting about the weather. “Better leave now. You don’t have a lot of time.”

“You’re just trying to get rid of me. Go on. Admit it.”

“I should be so lucky.” She snickers at her joke. “Believe it or not, I am on your side. And you’re missing the point.”

“What is the point?”

A silence follows, and I shift uncomfortably under her stare. “Are you even listening? The point is,” she says, “tlaalahua, tlapetzcahui in tlalticpac.”

A Nahua saying. The words of a tlamatini, a wise one. They are a reminder that the earth is a perilous place and one can easily fall. This means that the ideal path to walk is the one in balance, in the nepantla—the middle—where the tlalticpac is not slippery.

Order can become suffocating. It can halt progress, stunt growth. Chaos is more liberating, but it can get out of hand and become

destructive.

Thus the nepantla is necessary. The space between two worlds.

I must make order out of chaos and throw a little chaos into order.

I pick up my mask, understanding that a person’s life is not always their own. There is duty and obligation.

The padded guard around my chest feels heavy because I have grown unaccustomed to clothes. My belt which carries my dagger is also a little too big for me as I have become slimmer roaming the forest. I slide the Sword of Integrity in her scabbard and carry her on my back. I cast Zyanya an uneasy glance. She gives me a reassuring nod.

“I see you’ve reconsidered,” Amalia says as I emerge from the hut. She smiles one moment but frowns the next. “Wait. You’re leaving now? It’s the dead of night.”

“I know how to walk in the darkness.”

“Of course, you do.” Amalia smiles but rather feebly. “I will stay to help the sick. It can’t hurt me. The pox doesn’t visit you twice.”

I look around. “Where’s Eréndira?”

A screeching cry comes from above, and I tilt my head back to see the Owl Witch in the air, her great white wings flapping. Before I lower my gaze, Amalia manages to wrap her arms around my neck. “Gracias, Leonora.” My eyes bulge at the assault, and I wheeze for air as she nearly smothers me, but when she is about to let go, I tighten my grasp. Her comforting warmth is a reminder that I’m without my heat, my vital force.

Tonalli is so complex and confusing that even the tlamatini, the knowers of things, the philosophers—puzzle over it. It resists fitting into one meaning in particular. It’s impossible to fully grasp or describe. At least, not without a lot of effort and by reason alone.

God tonalli, however—how do I even begin to understand?

I force the thought to the back of my mind. The urgency of returning to the capital overtakes me. Mexico City was once my home, and I used to believe my brother would protect me if he ever learned my identity.

Will Jerónimo turn me away now?

Tezca haunts my mind. More than a year is a long time to be apart, and yet he’s never far from my thoughts. He is a shadow, present but

always just beyond my reach.

And Ichcatzin—he was already an enemy. I witnessed his ambition in Snake Mountain, his hunger for power. If Chipahua and Eréndira are convinced that he harbors a dark plot for Mexico, then we must heed the threat.

I have work to do. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...