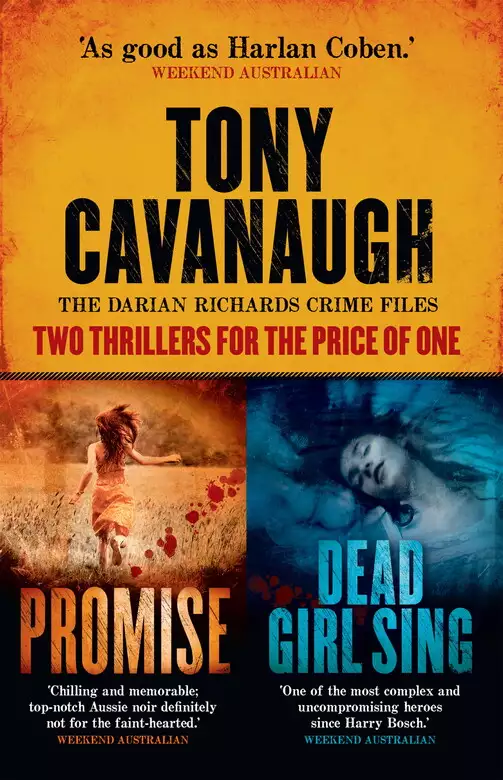

Darian Richards Crime Files

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

'There's a touch of Raymond lurking in Tony Cavanaugh's novels ? though his work owes as much to recent American hardboiled fiction such as that of Robert Crais, Michael Connelly and James Lee Burke.'? Weekend Australian A unique crime collection that brings together Tony Cavanaugh's powerful debut novel PROMISE and its critically acclaimed follow-up DEAD GIRL SING in one must-read volume. Top Homicide cop Darian Richards has been seeking out monsters for too long. He has promised one too many victim's families he will find the answers they need and it's taken its toll. After surviving a gunshot wound to the head he calls it quits and retires to the Sunshine Coast in an attempt to leave the demons behind. But he should have realised, there are demons everywhere and no place is safe. In these two gripping stand-alone novels, Darian Richards shows that when he makes up his mind to hunt out a killer, he'll stop at nothing to find them and deal with them ... his way!

Release date: January 28, 2014

Publisher: Hachette Australia

Print pages: 312

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Darian Richards Crime Files

Tony Cavanaugh

My gun and my phone; they were my life. Leaving my gun behind was easy. I just hurled it like a baseball into the ocean. I didn’t bother to watch its dead journey from the top of the cliff. I was staring at my phone. I knew I had to destroy it too, but I shoved it into my back pocket and kept walking. Later, I told myself.

Nine missed calls, same caller ID. I’d driven for eighteen hours, until the exhaustion had finally kicked in and I’d pulled off the highway. Six coffees later, I stared at the phone, which I’d carefully placed on the other side of the table as if it were a guest.

I was the only customer in the roadhouse. Out back there was a car park stretching deep into the night, crammed full of road trains and campervans and long-haul semis but they were still, quiet; everyone was asleep. A crumpled woman wearing a name tag that said Rosie had served me from behind a counter display of deep-fried day-old food. She had also been asleep when I walked in. Now she was staring at me, which is what most people would do to a man who doesn’t answer his phone when it rings and then buzzes and rings and then buzzes for twenty minutes. What’s wrong with you? Answer your phone. You’re hiding, you’re on the run, people are chasing you.

Rosie kept a dark watch on me. I knew she’d scanned the fastest way out in case her suspicions were confirmed and I was indeed a monster slowly awakening with each bolt of the coffee she reluctantly handed me. I guess my dubious behaviour was aggravated by my ring tone: Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Hey Joe’.

I knew the song well. I knew similar details of real domestic murder cases even better. The ring tone was a code, plugged into all of our phones, signalling a call from Family of Victim. Even though we had a lot of victims, spread over long years and across the reach of a vast city, it didn’t matter; the questions at the end of the line were always the same.

Rosie was starting to flinch on cue, as Jimi’s voice rumbled on about how Joe had gun-barrelled his woman into the ground because she looked at another man.

The same number flashed up on the caller ID. I’d memorised it long ago. I gave Rosie a wide smile and asked if she’d be so kind as to give me a seventh coffee and then picked up the phone and answered, my voice stretching back over eighteen hours and a thousand kilometres.

‘Hi.’

‘You resigned?’

I guess that after nine missed calls the shock had worn off; all that remained was anger and betrayal. Her voice was tired. I knew she had been crying; I knew this call would cast her into a dark journey from which there was no hope. She knew it too. I just had to confirm it, that’s all.

‘Yes,’ I said.

I heard an intake of breath: deep, slow, like the last echo from a sinking world. I burned away my shame and shut my eyes hard and kept them in a clinch while I waited for her to answer. From a place that seemed further than a thousand kilometres away I heard her say: ‘So, she’s dead.’

She hung up before I could reply. It would’ve been easier if I’d answered the first call. After nine unanswered attempts she’d distilled everything into a silent landscape of recrimination that would linger long after she hung up.

I looked out through the window. There must have been at least thirty semi-trailers and trucks in the car park. It was getting close to four in the morning; soon it would be dawn. A car sped past. I’d been following its approach since I noticed a tiny light, way off in the distance. Outside, beyond the neon spill from the roadhouse, it was black. No moon, no stars, no shape to the scrublands that stretched far and wide around me.

I put the phone down. In it were stored hundreds of contacts. I flipped off the back, removed the battery and eased out the SIM card. Before I allowed any feelings of doubt or remorse or guilt to surface, I snapped it in two.

Out in the car park, I shattered the rest of the phone with the heel of my boot. I picked up the pieces and threw them into an industrial rubbish bin. I heard the growl and rumble of a road train as its engine came to life. I heard the crunch of gravel as another truck began to ease towards the highway.

I walked towards my car. I had another six hundred kilometres to drive.

—

MY NAME IS Darian Richards. I grew up on a sheep farm, beneath a mountain called Disappointment in the soft valleys of the Western District. Every night I would lie in bed and stare out at the next mountain: it was called Misery. In the mornings I’d go outside and stare at a third mountain: it was called Despair. They were named a hundred years earlier by some fool explorer who was searching for The Great Inland Sea, which didn’t exist. Every time he climbed one of the mountains he got excited. Every time he reached its peak and looked across more land, he got … well, we know.

I couldn’t wait to get out of there. I had nightmares; it was as if the feelings he’d given these places as names were conspiring against me. Aged seven, I imagined I was already doomed. I knew there would be disappointments. But misery? Despair? Was that what the future held?

I was sixteen when I caught a lift with a truckie. I didn’t look back at those mountains. He dropped me off in the heart of Melbourne, two hours down the highway.

Three years later I was a Constable with the Victoria Police where I stayed, climbing the ranks until I had become Officer in Charge of the Homicide Squad. I earned a reputation as the top homicide investigator in the country. At the age of thirty I was also the youngest.

Most crews have a ninety per cent success rate. Ours was ninety-eight. People called me a legend. I wasn’t. I was just doing my job. Still, investigators from other cities would ring and ask my advice. Ministers from State governments would hassle my boss and try to get me seconded to clean up a murder that was lingering too long on their front pages.

I stayed in that job for sixteen years, until I could bear it no longer, which was exactly two weeks ago, when I abruptly resigned, having decided to relocate to a hastily purchased cottage on the Noosa River, which was about as far north on the east coast of Australia as I could go unless I entered the final thousands of kilometres of rural coastland that stretched up to the Timor Sea. I’d saved enough money to live a frugal life and sit by the river for a few years.

—

‘YOU PROMISE?’ I heard her voice echo, as I climbed into my car and closed the door. I started the engine, revved the accelerator. It was old, imported from America with left hand drive.

We’d been chasing the perp for about three years. It was always the same. A girl boards a train. Vanishes. A week later she’s released into a multi-storey car park, wandering, drugged, dazed, unsure if she’s alive; more likely she thinks she’s dead, in an enclosed world of concrete spirals and parked cars. Always dressed in the clothes of his previous victim, ripped, shredded, now tattered, rags held together so loosely they flutter to the ground, leaving her naked by the time she’s found. She’s been living in a collapse of darkness and time. He said nothing to her. He raped her repeatedly, endlessly. Then she awakes, a week later, among parked cars. It’s not the same world that it was a week before.

He’d stolen his ninth, Lorna, when I heard the question asked by her mother, Diane, as I was standing in the kitchen of their home, out of the way of my crew as they searched for any trail that might link the victim’s stable world to his prowling one.

Diane knew how he worked. Everybody knew. Newspapers, television, radio reports were full of breathless speculation. He may as well have had his own blog. He was lord of the city and all of its homes.

‘It’s him, isn’t it?’ she asked in a voice only just controlling the terror. She was strong. She’d stay with us until her girl was returned. Most parents don’t. They freeze and turn inwards, their lives already ruined.

‘Yeah, it is,’ I replied.

‘Then he will release her, won’t he? Like the others, in about a week?’

I turned to her as she asked another question: ‘She’ll come back to me, won’t she?’

‘If it’s him,’ I said, ‘and we have every reason to believe it is him, then yes, Lorna will–’

I’d already said too much.

‘–most likely be released.’

She stepped up to me and I felt her hand close around mine and hold it tightly in a soft embrace – something I hadn’t expected or anticipated; she’d caught me off guard – and she said: ‘You promise?’

I just wanted the desperation to stop. Not only hers.

‘Yes,’ I replied.

—

LORNA DIDN’T COME home after a week or after two; weeks became months and still she didn’t come home.

After the second month I began to drop by and see Diane. Every month. She clung to me. My promise kept her going, feeding the hope that Lorna would one day return. My visits confirmed we were still investigating. I was on the case. I was active. We were closing in on the perp. In truth we were stranded. But I’d made a promise.

Once, late, after midnight, after my reassurances, she took my hand again and started to lead me towards her bed. I wanted her as much as she did me, for different reasons, all of them selfish. I pulled my hand away and left. Some cops do sleep with victims or their family members. Maybe they need it to keep going, to keep hunting or to find some joy in a world of grim trauma. I didn’t. But I wanted to.

—

I DROVE AWAY from the roadhouse, back onto the highway with her voice in my head.

She was right: her daughter was dead. I knew it after the first week passed and she didn’t surface. I knew it every time I visited her, assuring her, giving her hope when I knew there was only despair, made worse by my promise. It could have been worse had I not pulled my hand away, compounding deceit with the embrace of my body into hers.

Lorna wasn’t coming home. Nor were the other seven girls who boarded trains after her. We never found him. He’s still riding trains.

I stared ahead, driving faster, and pushed images of Diane – naked now, her bra unclasped and falling softly onto the carpet beneath us, her body pressing into mine – into darkness. All I could see was the road.

IT WAS A YEAR SINCE I LEFT THAT ROADHOUSE. A YEAR SINCE I tried to walk away from darkness.

A breeze swept up from the Noosa River, in through my house, a rickety wooden cottage built by a fisherman about a hundred years ago. All that lies between my living room and the water is grass, palm trees and a hammock. When it storms I get a little nervous because the house shakes.

I was staring at a photo of a young girl on the front page of the local newspaper. Another Girl Vanishes. Killer Claims Number 6.

Her name was Brianna.

I listened to the pounding of the surf from the beach a kilometre downstream where the Pacific Ocean sweeps through a narrow channel, over a sandbank with deep tangles of mangrove on either side.

Brianna looked as if she hadn’t yet decided whether she would smile or be serious for the photo. I wondered who took it and if it had been taken inside or outside; the background was flat and grey. It wasn’t intended to run on the front page of a newspaper.

I turned away from the photo and picked up the phone.

‘Casey’s Antique and Second-hand Emporium,’ said Casey, ‘a place of mystery and treasure.’

‘It’s Darian. I thought I’d come over–’

‘Darian?’ he interrupted. ‘The bad man from the dangerous streets of Melbourne,’ he added, chuckling.

‘–maybe later today,’ I finished. A small tinnie floated past me, drifting along the current, downstream in the direction of the sandbar. Standing in the boat was a local fisherman, an old guy with spidery legs firmly spread so he didn’t lose balance. Without looking in my direction, he waved. He sells me mud crabs when they’re in the river.

‘Stay for dinner,’ said Casey as I waved back. I hate waving but I like mud crabs.

‘Thanks. I will.’

There was a pause. ‘Cool,’ he said slowly.

It wasn’t cool. I never stayed for dinner; it had even become part of our friendship, a signature exchange of, ‘Stay for dinner,’ always met with, ‘Next time.’ That’s how it worked. He didn’t really mean it because his girlfriend doesn’t like me and I didn’t mean it because I don’t like going out for dinner.

I like a simple life, a private life, a life without distraction. This happily leads me to the exclusion of people. Most people I’ve met want to talk about the patterns of the fish in the river or the clouds in the sky or, the very worst, how their baby is growing up so well. Don’t get me wrong: I devoted my life to the protection of people. I just don’t want to have to talk about it. I adore the writings and the songs and the poems and the thoughts of people – mostly dead people – but not a regular engagement with them. Casey was one of two exceptions.

He spoke carefully. ‘Maria gets home at six.’

Maria was Casey’s girlfriend, a Senior Constable in the Noosa Crime Investigation Branch. Her staggering beauty was matched by her popularity at the station; she was also very clever. The boys told her things. Trying to impress the pretty girl. Male cops, generally speaking, are dumb. Some are wooden-plank dumb, some are rodent dumb. Most are just moron dumb. Female cops, on the other hand, are not dumb at all.

Maria is wary of me. All the cops on the Sunshine Coast are wary of me. Small-town cops don’t do respect. They do superiority. I didn’t want to rumble the petty jealousies in the station up on the hill, so I drove into town as anonymously as I could, albeit in a bright red Studebaker convertible. I stayed low, never told anyone where I came from or what I did, and I always waved back. This was about as successful as taking out a full-page ad in the local paper.

‘I thought I’d get there ’bout four,’ I told Casey. ‘I’ll go through Tewantin. Buy some wine.’

‘She likes rosé. French–’

‘Chateau St Paul,’ I said. ‘I know.’

‘Hey, stop by the newsagent, get me Rolling Stone, get me some other magazines too. But nothing moron.’ Retired people are strange; they develop weird habits. Casey’s is that he never goes into shops. Mine is that I wave at people.

There was silence. He was thinking. I didn’t intrude. And then he asked: ‘Should I be prepared?’

‘Yeah. Will that be a problem?’ I said, referring to many things, one being Maria.

‘No.’

‘I need a Beretta.’

‘See you ’round four,’ he said and hung up. I could’ve told him I needed a pencil.

—

CASEY LACK USED to manage a strip joint at the end of a brick lane close to the Melbourne dockyards. One night it exploded in a gigantic fireball that rose to over three hundred metres, spewing a black rain into a January night; an explosion so loud it woke old people ten kilometres away and set dogs barking until dawn, which was about the time I was shoving aside a fireman from a charcoal awning to unearth yet another victim, her body shattered into pieces like the others.

Casey and I became friends after he helped me investigate the deaths of the eleven strippers who were killed that night. He knew the Twenty-Four were responsible. I nailed them. Casey loved the strippers and was shocked anyone would harm them, let alone blow them to pieces. After giving evidence he fled the icy web of Melbourne, drove north and retired on six acres in the Noosa hinterland. Like everyone who retires up here he got bored, and he opened a junkyard, a place of mystery and treasure.

I have two cars. In one I’m alive. In the other I’m driving. I inherited the ’64 Studebaker Champion Coupe from an ageing Algerian gangster whose life I’d saved back in Melbourne. It has fins. It drives like a ballistic monster. Behind its wheel I’m immortal.

I purchased the 1990-something Toyota LandCruiser soon after realising that the local terrain wasn’t all smooth and flat. It’s off-white. It goes. It climbs hills that are almost vertical. It knocks down small trees that get in the way. Behind its wheel I’m anonymous.

I put the LandCruiser into reverse and eased out carefully so as not to scrape the red inheritance.

Up here people are friendly. They wave at you.

This was what Jacinta-something, one of my neighbours, was doing as I crushed the gears from reverse into first and hammered the car, quickly, into Gympie Terrace. I pretended I didn’t see her. That was better than making eye contact. Eye contact could lead to familiarity; she might even think she’d be able to drop by. People up here are like that. You have to be on your guard.

Gympie Terrace runs along the river, through Noosaville to Tewantin. Old wooden Queenslanders – cottages held high off the ground by thick wooden poles of forest hardwood painted white – line the broken footpaths filled with puddles of brown water. It stormed last night. The branches of frangipani and jacaranda trees twist and mingle, becoming walls of green, purple and white flowers, sometimes reaching high enough to form a canopy over parts of the road.

I drove across the bridge that spans Lake Weyba, still and calm, its surface a mirror. Maybe half a kilometre wide, on the other side of its shore was the Wooroi Forest. Rising up from inside it was a black mountain. Shaped like a dagger, it was called Tinbeerwah. The landscape wasn’t enough to distract me.

Six girls had vanished over fourteen months. All blonde and pretty. The youngest was thirteen; the oldest was sixteen. The cops listed them as ‘missing’ or ‘vanished’ – that’s what they have to say if they don’t have a body. But I knew those girls were all dead.

Jenny Brown was the first. She vanished sometime after four in the afternoon on Saturday the fifteenth of October. Everyone – except for her parents and her friends and anybody who knew her – thought she’d run away. Especially the cops, who were the ones who said she’d run away. They would’ve allowed a good two or three minutes before arriving at that conclusion. By the time they’d reached the front gate of her home, before they’d even walked across the road and climbed into their cruiser, they would’ve forgotten Jenny Brown existed.

That’s the type of police work I used to call DD: Dumb and Disdain.

After two more girls vanished, also blonde and pretty, the cops realised it was hard to say ‘coincidence’ any longer. There was a pattern they couldn’t ignore.

Jessica Crow was the fourth. Wednesday, the twenty-third of February. She was walking along Sunshine Beach and then through the National Park, a thick forest that traverses a headland between the calm Laguna Bay and the ocean. Thousands walk through it, along a tourist path, every year. There are places to rest and signposts telling you dead facts about the koalas that live in the trees. As Jessica walked along this path I was down on the beach, walking barefoot along the sand. I’d noticed a young Asian girl. She couldn’t swim and she looked like she was in trouble. In Australia we lose a few Jap tourists a year because they can’t swim. There is a strong current that ebbs beneath the water’s languid surface. I decided to see if she actually was in trouble.

I stripped off my T-shirt and hurled into the water, towards her. She didn’t understand what I said, so I tried a bit of sign language, to which she responded by bolting like a jet ski until she reached the shoreline; there she ran on to the sand, grabbed her towel and was up the wooden steps and into the car park in record time.

As I waded back to the comfort of land, less than a kilometre away Jessica Crow was staring into the last set of eyes she would ever see. Her body, like the bodies of the other girls, has never been found.

Two months later his fifth victim, Carol Morales, was taken. I was trying real hard to ignore these vanishings. This part of the local environment wasn’t expected nor was a rampaging serial killer on the loose part of the early retirement plan. I was doing a good job of pretending the killer wasn’t my problem but the growing body count and the knowledge that the local cops didn’t have the expertise to handle it was starting to oppress me at night, when I slept. I can erase the thoughts during the day and stare at my friends the pelicans. At night I’m as much a helpless victim as those girls.

Brianna was taken at 3.38 on Thursday afternoon on her way home from school. Three days ago. Last seen in the Noosa Civic shopping mall. Brianna played classical music. Piano. At her year nine end-of-year school concert she shocked some parents with her choice: ‘Stairway to Heaven’. But when she’d finished, the applause lasted nearly five minutes and she had tears in her eyes as she stood before the parents and teachers and her school friends. She’d killed it, big time. Even the headmaster climbed out of his seat and congratulated her for her amazing talent and bravery.

‘Imagine that,’ he was quoted in the local newspaper. ‘Who would have thought, Led Zeppelin at the end-of-year school concert? Our Brianna Nichols is going places.’

I had come up here to retire early, and that had been working, until about three o’clock this morning when I could bear the nightmares and the whispering voices no longer. So now I was going to find this guy because the cops couldn’t.

Then I was going to make sure he’d never kill again. I was going to erase him from the face of the earth.

—

I PICKED OUT Rolling Stone. And The New Yorker and Q. Lady Gaga was on the cover of Q. Nude. That was the clincher, although I’d tell Casey Q was way cooler for a guy like him, second-hand dealer and all.

The place was packed. Cliff, the owner, was busy selling tickets to a twenty-eight million dollar Lotto prize. He used to be a coffee farmer, retired up here but soon got bored. Then, when the newsagency went up for sale – after its owner had a sudden and apparently spectacular heart attack while stacking new issues of Playboy, Penthouse and Hustler into his shelves – he purchased the business. This I learned, without having asked, from Silvio the Onion – ‘call me Sil’ – who owns the fish-and-chip joint near my house. Sil the Onion keeps me informed, even though I ask him not to.

The newsagency is in the main street of Tewantin, the next town along the river after Noosaville. Tourists don’t come to Tewantin. The Sunshine Coast Council offices are in Tewantin. Tewantin is where you go to get your driver’s licence.

Cliff’s daughter was behind the counter. She was about fourteen. She was pretty and blonde. She wore a short skirt and a singlet cut into a v around the neck to reveal a tiny cleavage and cut short around the waist to reveal her navel. She smiled at me in a sweet and innocent way, the sort of smile some guys read as an invitation.

‘You like Lady Gaga?’ she asked as she zapped the magazine’s barcode.

‘Only the first album. In danger of selling out.’

‘Yeah, maybe, but she is amazing.’ She smiled at me again, but differently, like we shared something in common. Lady Gaga. Check the wit and stay silent, I told myself.

‘Doing some bushwalking?’ she asked as she zapped a local map, the only accurate chart of creeks, estuaries, forests and national parks in the Sunshine Coast.

I smiled and sort of nodded while I paid and then said: ‘Bye.’

‘See ya, Mr Richards,’ she called out. Even the newsagent’s daughter knows my name. I turned back to nod or do something. There was that smile again. Big, genuine and – I couldn’t help feeling –

Dangerous. I went on my way.

‘Darian!’ Cliff was running towards me. What now?

‘I’m sorry,’ he said as he reached me. We stood on the footpath. For what? I wondered.

‘But, you know …’ he said. He paused awkwardly. I stared at him. People were passing us. It was hot. The sun was hot, the footpath was hot.

‘What do you want to say?’ I said even though I knew where this was going; I’d already got to the end of the conversation we were about to have.

‘Her. Henna.’ He jerked his head in the direction of his daughter. ‘Look at her,’ he said, almost as an accusation.

I didn’t. He went on: ‘She’s exactly the type of girl he targets, isn’t she?’

I didn’t say anything.

‘Look: she’s blonde, she’s fifteen, she’s beautiful.’

I waited.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said once more, in a faltering voice.

‘What is it you want to ask me?’

‘You were a homicide cop.’

It was that full-page advertisement I took out.

‘I just want some advice. Sorry.’

‘Stop saying sorry. Ask. Now.’ I’m not big on patience.

He took a deep breath, looked around and leaned in, close, like we were brothers. He whispered: ‘Should I get her a gun? A pistol, just a little one she could keep in her bag, when she’s out at night, or alone, to keep her safe, from him. She’s exactly the type he’s taking. Look: she’s a fucking target.’ He was shaking.

I looked around the street. People were watching us. They probably knew what we were talking about. Fear permeates. When a killer is on the loose and living within your community the whole world changes. You don’t walk down the street like you used to. Now everybody – even you – is wondering. Is it him? Or him? Or that guy; he’s always been creepy-looking. The town was being strangled by fear and I was standing right in the middle of it.

‘She’d be committing a serious criminal offence carrying a firearm.’

‘Would that matter? If she was taken?’ He was angry.

‘You’d teach her how to use the gun?’

‘Yes.’

‘You’d teach her how to distinguish between a drunk who wants to try it on, a guy who scares her and a serial killer?’

He didn’t say anything.

‘Here’s my advice: do not buy her a gun. If she is ever in the company of a serial killer she won’t know it because he’ll be just like her favourite uncle or big brother. And if, in the unlikely event that she is grabbed, she’ll have ten seconds, maybe, if she’s lucky. Ten seconds to act, and those ten seconds will be full of one thing only: terror. Okay?’

‘Okay,’ he said slowly.

‘Okay. That’s when the adrenaline kicks in. Only a person trained to operate and think clearly in those circumstances can use a gun to terminate the threat.’

He nodded.

‘Do the following things. Engage a security company to monitor her movements. Buy her two GPS trackers; make sure they are on her body at all times. The first GPS she places. That’s the one he would find. The second has to be very small and more powerful than the first. Have this one attached between two of her toes. It’s about the only area of a girl’s body they don’t explore until later.’

He was silent.

‘Are you thinking about how much this will cost?’ I asked.

He looked startled and tried to cover his embarrassment.

‘Don’t think about how much it will cost.’ Then I walked away, determined to buy all future magazines at the Cooroy newsagency, even though it was further to drive.

COPS DON’T LIKE IT WHEN THEY THINK SOMEONE IS INTRUDING on their investigation, even dumb cops or cops out of their depth or cops desperate for help and guidance.

With that in mind I parked the LandCruiser under a massive willow tree on the side of a dead-end dirt road fringed with a forest of palm and gum trees. I looked across to the house in which Jenny Brown had lived. A cottage, made out of wood sometime in the 1930s, no later. It stood high off the ground, held up by wooden beams. It had been painted back then but not since. It was a home for poor people back then, and now. Under the house, between the wooden beams, was a scattering of junk: a TV, a couch, an assortment of rusty outboard engines and a small upturned boat. The yard was full of thick grass, unopened mail and newspapers rolled up in plastic.

This was the beginning. When the cops came to investigate Jenny’s disappearance, they weren’t investigating a serial killer. Their interview with the mother, days after the killer had examined the house, as I was doing now, would have been ruinously thin. Incomplete. Irrelevant. Jenny was a runaway, an inconvenience. They should have – but wouldn’t have – thought to ask: Have you noticed any strangers outside lately?

I would come back here, soon. It didn’t seem like there was anyone inside but even if there was, I wasn’t ready. I just needed to see her home, get my first inkling of who she was and why our guy started with her. Why her? She triggered him. Why?

I drove past the other houses, as derelict and forgotten as Jenny’s, until the road gave way to a forest of ghost gums and paperbark trees. It came to an end in a wide circle for a smooth turn back to the way I had come. I swung the wheel and then stopped.

There was a track leading into the bush. Maybe it led to nothing, or maybe it led to a place where kids smoked or teenagers fondled, or maybe it was just a short cut to somewhere else. Whatever it was, it looked like it led to a place of secrets.

I got out to look.

Thickets of dry scrub edged either side of the track. About eighty metres in I found a clearing, just off a turn, hidden from view by dense bush and a massive sprawling tree trunk. I pushed away the bush as I walked in and found myself in a small and secluded camping spot. Somebody had made it. Why? Did it have anything to do with Jenny or had I just stumbled into the passion palace for the local kids?

I tr

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...