- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

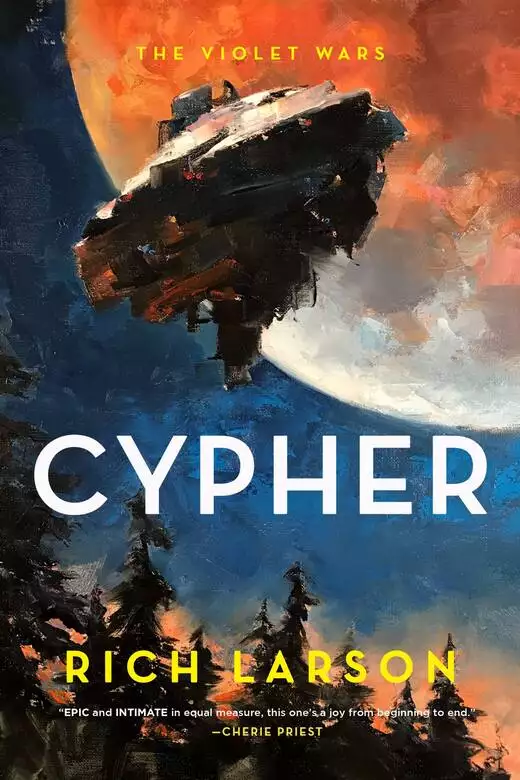

The gripping sequel to Rich Larson's beautiful and gut-wrenching debut Annex about two outsiders surviving, fighting back, and finding family at the end of the world.

The invasion is over, but not all the aliens are gone. As the outside world learns what happened to the city, Violet and Bo struggle to keep their ally Gloom hidden from prying eyes.

Those in power believe he is the key to unlocking the invaders' technology, and will stop at nothing to capture him.

All the while, the invasion's survivors are being drawn to a mysterious anomaly that might be their destruction -- or their salvation from an even greater threat.

The Violet Wars

Annex

Cypher

Release date: September 8, 2020

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Cypher

Rich Larson

An enormous rust-brown bowlship, pitted and scarred from its journey, descends through Ymir’s dark howling sky. Drones stream upward from the ice field to meet it, swarming like insects, tasting its hull with electromagnetic mouths and asking after its cargo. The bowlship reports nickel alloy, raw hydrogen, an inconsequential amount of human freight.

When it sinks into the frost-coated docking cradle, the heat of its stabilizers turns ice to vapor. A thunderhead of steam slams out in all directions. The bowlship groans and shudders and finally comes to rest. It opens itself to the tunnels below, where automated laborers and exoskelled dockhands await to begin unloading.

Past the alloy stores, past the hydrogen tanks, in the darkest gut of the ship: the torpor pool. Bodies churn in a slow current around the reactor, tangling and untangling, a drifting mass of frosty flesh. They are skeletal, emaciated from the long haul, and their skins are coated a slick milky white by the stasis fluid. They are clinically dead, but not legally corpses.

At the far end of the pool, a door folds open. Two dockhands step through in a gush of steam. One is carrying a long hooked pole on her shoulder. A tiny drone is clinging to the end.

“Rerouted the whole ship for one fucking body,” she says. “Must be a company man.”

“We giving him a private thaw, then?”

“Sending him straight north. They’ll thaw him on the way.”

The drone darts ahead of them, fairylike on gossamer rotors. Its scarlet laser plays over the drifting bodies. The dockhands wait while a spiny walkway assembles itself, sprouting from the reddish-brown wall to extend across the torpor pool. They trudge forward, footsteps echoing in the cathedralic space.

The drone slides under the surface of the pool with a muted gurgle. The dockhands follow its red light, and the one with the pole slings it off her shoulder. She eases it into the stasis fluid, poking between bodies until the magnetic hook finds a particular harness.

Together, the dockhands dredge their catch up out of the pool. The walkway grows a socket to hold the base of the pole. It slides inside with a rasp and click, and the man is hoisted into the air like a puppet, dripping fluid. The dockhands peer at him.

He’s small, pallid-skinned and dark-haired. He has no lower jaw: between the blue curve of his upper lip and the rippled flesh of his throat there is nothing but medical membrane.

“Ugly fucker,” the first dockhand says. She points to a geometric spiral on his neck, the biotech tattoo the drone scanned to identify him. “Company man, though. I was right.”

“Looks a bit like you.” The other dockhand blinks. “Sending him north, you said? Maybe he a cold-blood, then. A cold-blood company man.”

“No such thing.”

But when they load the body into a drifting sarcophagus for transport, she sees shins and feet cratered with scars. Her black eyes widen, then narrow, and then she spits. It trickles down the side of the man’s frozen face.

“What’s that about, then?”

She stares down at the body. “No such thing as a cold-blood company man,” she says. “Only traitors.”

“So I was right.” He smirks. “Them cold-blood geneprints are real distinct. Sealie, yeah?”

“Half, maybe. Half-blood.” She hinges the sarcophagus shut. “Company’s mad to send him north. He’ll be leaving in a spraybag.”

They guide the body across the dark walkway, over the torpor pool, following the dancing drone.

Yorick wakes up dead, which is never comfortable. His chest is a clamp, lungs frozen, no heartbeat. His limbs are phantom. The hindbrain panic swallows him whole. He knows nothing except that he is alone and terrified and in the dark; every sensory-starved nerve in his body is screaming it, and then—

A jolt of electricity digs its teeth in, and his heart stutters back into motion. He owns his chest muscles again, so he sucks down a breath, ballooning all the crumpled alveoli in his lungs. The first one always feels like sucking back broken glass. A rehearsed thought comes to him: Nothing is wrong. You’re coming out of torpor. Nothing is wrong. You’re coming out of torpor.

He gasps. Bucks. Waits for the firestorm in his nervous system to subside, for the world to stop lurching from side to side. He works on proprioception, finding his body in space. His arms and legs are spread-eagled, punctured in a dozen places by tubes that are pumping him full of newly brewed blood. A diagnostic droid is scuttling up and down his torso.

His prosthetic mandible is missing. Cold dry air rasps in his wound.

“Welcome back from the River Styx, Yorick.”

Yorick’s eyes are crusted over. He works his lids until he manages to free one from the gound. First he sees only a dark gray haze. Next he sees an orange blur, flickering through his field of vision too quickly to track. He knows from experience that this is the orange suit of a thaw technician.

“It’s been a long time since we spoke last,” the voice says. “Nearly two decades here. Half that for you, I believe, with all the time spent in torpor. I can see you’ve done good work in that span. Eight successful hunts. Do they ever permit you to keep trophies from them?”

Yorick knows the voice. His gut coils tight.

“I still think you did your very best work right here with me, of course,” the voice continues. “Back in those early days of Subjugation.”

The tattoo on his neck prickles. He knows the voice, but it was one he never thought he would hear again, and if he’s hearing it again it means—

“I’m afraid this thaw’s not taking place on Munin. You were rerouted in transit to solve a more pressing problem here on Ymir.”

No.

No, no, fucking no.

“That seems to have spiked your adrenals, Yorick. Thrilled to be home, I expect.”

Memories crash in. Phosphorescent flares lighting up the ice field, the skull-pulping sound of smart mines going off. An anonymous body shredded to pieces, steaming, another barely intact, wriggling through the snow and slicking blood behind. And the owner of the voice is there, too, one bony hand on his shoulder, saying civilization costs.

“I’m an administrator here now,” Gausta says, voice sintered with faint surprise, as if she’s still marveling at the fact. “Living just to the east of your old haunts, overseeing security for all of Ymir’s northern-hemisphere extraction and refinery sites. Which brings us to why you’re here.”

Yorick wants to rage, to beg, to say that he will go anywhere, absolutely anywhere. Just not Ymir, the slushball of piss on the edge of the colony maps, the birthplace he swore to never set foot on again. But he can’t speak without his mandible. He only manages an animal groan that startles the thaw technician.

“Eight days ago a xenotech incident suspended all labor in the Polar Seven Mine,” Gausta continues. “There were grendels here after all, and we finally dug far enough to wake one up.”

Yorick isn’t afraid of the grendel. He’s killed the grendel a dozen times on a dozen worlds; it’s the job the company trained him for. He’s afraid of everything else.

“It butchered a few miners and then disappeared, as a grendel is wont to do,” Gausta says. “But the attack has reinvigorated anti-company sentiment here in the north. There are rumors of a strike. Fainter rumors of insurrection. We tread on thin ice.”

Yorick finally pries his other eye open. The orange blob of the technician sharpens. Above it, he sees the hazy outline of a holo projected on a low plaster ceiling. He can’t make out Dam Gausta’s features, but he recognizes the predatory angles of her body. He remembers her in a chamsuit, her long limbs dissolving into the ashy snow behind her, her hooded head turning dark as the starless sky. Before that, in a bright yellow coat.

“The algorithm balked when I chose you for this job, Yorick,” Gausta says. “You were only the third-nearest option, and the differential in transit cost was significant.”

Yorick forces the memories down and works on focusing his eyes. Gausta’s face comes clear, the wolfish gaze and jutting bones and swirled vitiligo skin. She’s aged less than he has in twice the years, as perfect and awful as ever, the gengineered telomeres of a company higher-up at work. Her eyes are unchanged, the same silvery pits.

“But machine minds are so limited when it comes to sociohistorical context.” Gausta gives her scalpel smile. “You understand this place, Yorick. Every day the mine remains shut and the grendel roams free, not only does the company bleed profit, but the locals’ discontent festers. Stability degrades.”

But it will never be stable up here; Yorick wants to scream it at her. The first colonists to come to Ymir were exiles and radicals. The generations born after were shaped by the cold and the dark into paranoid tribalists. He left because he didn’t want to die, and now the company has returned him with a tattoo on his neck, a target on his back.

Gausta reads his ruined face, or more likely his jolting heartbeat. “It’s been twenty years here,” she says. “And you’ve undergone quite a spectacular rendering of flesh. Nobody will recognize you, Yorick. So long as you do your work quickly, and tread lightly on the ice.”

Gausta leaves, but her avatar lingers to give Yorick logistics:

He will have one day to recover from torpor before he conducts his initial investigation of the site, accompanied by the Polar Seven’s interim overseer. His pseudonym will be Oxo Bellica, to avoid Yorick Metu’s lingering notoriety. His hunting equipment was not transferred, but will be reprinted pending ansible clearance. His clothing and mandible are nearly finished. He is three hours out from Reconciliation.

That last part jags him, but explains why the world has not stopped lurching from side to side. They loaded him straight from his bowlship onto the only passenger skid that heads north. Nobody in the north would ever call it Reconciliation, of course. It’s the Cut to them, was the Cut before the company ever arrived.

Unless things have changed in the past twenty years—Yorick considers that faint possibility as the thaw technician retracts the tubes, freeing him from his plastic web. They’re gentle with the flap of scar tissue and reconstructed flesh where his jaw should be.

“I can give you one more wake-up shot,” they say, muffled by their mask. “Nod if you want it.”

Yorick has been working mostly on clenching and unclenching his toes, wriggling his fingers, but he manages to bob his head up and down. Microneedles prick his neck, and a half second later he feels a chemical cloudburst, stimulants flooding his whole body. It rubs his nerves raw and makes him momentarily want to vomit.

The bed folds, easing him upright, and the diagnostic droid crawls off him.

“You ready to try walking?” the technician asks.

Yorick nods.

The technician nods at a chugging printer at the end of the compartment. “We’ll go to that printer. Get you your clothes and your prosthesis.”

Yorick grunts. He draws a deep breath, rubs the knotted muscles in his thighs. He holds the thaw technician’s shoulder as he takes his first shaky step, timing it to the sway of the skid. He takes a second. A third. On the fourth his knees buckle, his head rushes, and he nearly takes the technician to the floor with him.

“Today’s not going to be pleasant for you,” they mutter. “Thawing you this fast, yanking you straight off the freighter without calibrating your chemicals.”

Yorick shrugs his bony shoulders, gives the technician his own hideous version of a smile. He was not expecting a pleasant day anyway.

They stand him in front of the printer nozzle, just long enough for a patchy gray undersuit of spiderwool, then help him into his high-collared coat. The color is wrong, black instead of canary yellow, but it fits the same on every world. The boots are heated this time. He puts them on while he watches the printer work. It disgorges his rucksack next, a fabric shell that scuttles along on four stubby pneumatic limbs.

“Your prosthesis should be inside,” the technician says. “Do you want my help with it?”

Yorick shakes his head, because attaching the mandible is something he does himself, alone.

“Okay.” The technician scratches under their mask. “I’m getting off at Sants. I recommend you stay in here and rest. You’re going to be sleepsick for a while. Fatigue, nausea, some body dissociation. Probably hit the peak in four or five hours.” Their eyes flick to the tattoo on Yorick’s neck, then away. “But you can do whatever you like. Your vitals cleared threshold.”

A door dilates at the back of the compartment, and Yorick catches a brief glimpse of rocking corridor as the technician departs. He smells a whiff of dust and machine oil. Then he is alone with himself. He needs to rectify that quickly, so he rubs his thumb and pinkie together to beckon the rucksack.

It ambles over to him, sliding slightly with the motion of the skid, and peels open to display the exact same things as always. This is a comfort to him. Whatever world he wakes up on, the small orderly one inside the rucksack is unchanged. Basic black tablet. Coiled neurocable. Disinfectant brush. Microneedle injector. Rolls of gelflesh.

His mandible is in a slab of clear putty, still warm from the printer. He worms his hand past it, to the bottom of the rucksack, and finds the drug canisters. Immunosuppressors for his wound, phedrine for his mood—neutered company stuff, of course, not street-grade. But right now, even company phedrine will do.

He loads his injector with trembly fingers. When the microneedles punch through his capillaries it feels almost like sunshine. It’s the closest he will get to it on Ymir.

Yorick watches through the window as the skid churns along, throwing up a shroud of shattered ice in their wake. The sky is a black hole, all traces of starshine concealed by dense cloud. The only illumination comes from the skid’s running lights, a sickly green glow, the bioluminescence of some eyeless creature gliding along the primordial seafloor.

They’ve already passed the cities, passed the graveyard of one-way ships that brought Ymir’s first settlers and are still being digested for salvage a century later. They’ve passed the petrified forests and the airfarms that replaced them. This far north, the entire world is a single sheet of wind-scoured ice.

Yorick spots a herd of frostskimmers in the distance, leaping and gliding, attracted by the light of the skid. He observes them for a moment, then lets his phedrine high pull him farther along the swaying corridor. He hardly even minds that he is on Ymir, that he is heading north, that he is going to die there. His whole body is full of warm helium. He has the mandible tucked up under one armpit. His vague goal is finding the lavatory pod, where he will attach it.

The skid was noisy earlier, echoing with drunken shouts and laughter, a crowd of miners and a few fat-hunters swilling foamy bacterial beer in the corridor. Yorick kept his coat zipped to hide his lower face as he passed them by, but nobody glanced, too preoccupied by a wager: a tall bulky offworlder with an eye implant had bet they could contort themselves to fit in a standard-size sleepstack, claimed they were all cartilage, nephew, skeletal mod.

Now the corridor is dark, lumes dimmed by consensus, and half the skid’s passengers have shelved themselves into the miniature mausoleum to rest, not to win wagers. Yorick suspects they are trying to sync for the same work rotation. He keeps his footfalls soft, trying to outquiet the rucksack padding silently behind him.

There’s another window before the lavatory pod, and through it Yorick sees the one interruption to Ymir’s cold horizon. It grows in the distance, a warped mound erupting from the ice, sheathed in nanocarbon scaffolding and coated in buzzing drones. As always, it’s difficult to judge the size of it. Even veiled in human tech, the original architecture of the ansible has a disorientating effect. Workers take a certain depressant drug to mitigate it.

A memory flashes through Yorick’s head, neural sheet lightning: trekking out to the ansible when he was fourteen, maybe fifteen, clambering over the blockade, seeing who could creep closest before the nausea and the brain-bend were too much to handle. He remembers the alien structure as an enormous face, carved from black rock, sutured with eerie blue lights.

It’s the ansible that drew the first colonists here, the ansible that marks Ymir as one of the Oldies’ abandoned worlds. The company took it over during Subjugation, and Yorick doubts anyone clambers over the blockade anymore. Not if they want to keep their skulls intact.

He feels unease trickle, icy, through his phedrine high. Partly for the memories, which he knows will only get worse the longer he’s here. Partly because passing the ansible means they are barely an hour from the Cut. He knows this journey, this skid north, from what he thought was his very last day on Ymir. That day ended very badly.

Someone is puking in the lavatory pod. Muted sounds, throat and splash. Yorick’s shrunken stomach gives a sympathetic ripple. He goes the other way, finds a vacant sleepstack. He peels down his coat just long enough for it to scan his company tattoo, then climbs inside.

The concrete cube of the apartment. Yorick and Thello are small, crouched on the floor, playing with rubbery yellow dolls they got from the toy printer. One is an exoskelled soldier holding a tiny howler. The other is a monster, a mass of spines and tendrils.

Their mother looms over them. “Where’d this come from, then?”

Her anger is a pressure drop; Yorick feels his chest tightening, his ears ringing. She doesn’t mean the toys. She means the tablet dangling from her hand, the basic black square that the company men were giving away last week near the junk recyclers. She holds it casually, asks the question calmly, but Yorick can hear the needles underneath.

“Didn’t steal it,” Thello says. “Swear truth. It was for free.”

“What did they tell you it’s for?” their mother asks. The needles are sharpening. Yorick knows, instinctively, that it would have been better if Thello had stolen it.

“You can go on the net with it,” Thello says, face flickering confusion. “Play. Learn things.”

“Learn things from the company,” their mother says, snarling the last word. “The Cut existed before they showed up. You learn that?”

Thello shakes his head, gledges pleadingly at Yorick. Yorick ignores him. Thello deserves this, for hiding it under the gelbed instead of in the spot behind the cooker.

“It was just smaller, that’s all. Simpler.” Their mother runs her frayed nail across the tablet’s surface. “Just a chasm in the ice, deep enough to wait out the blizzards. Then we find the first vein of zinc, and suddenly the company wants to make friends.”

“Nothing like that,” Thello mumbles. “Learned about the Oldies, about the grendels—”

“So they come with buildbots, with bubblefabs, with air,” their mother interrupts. “With gene scanners, credit, implants, and contracts. With smiles here.” She drags a corner of her mouth upward with one finger. “And knives behind their backs.”

Yorick has heard these words, or similar ones, a hundred times. He knows to nod and keep his mouth shut.

“They’re not our friends.” She holds out the tablet to Thello. “Smash it.”

Thello, stupid little Thello, flushing and defiant, shakes his head. Yorick wants to hiss in his ear: you can get another one, it doesn’t matter, just smash it.

“Or I will,” their mother says, raising the tablet high.

Thello’s eyes dart left. He shakes his head again, and this time he mutters something, too. “Our da, though. Our da was a company man. Everyone says.”

Her free hand snaps out; there’s the loud flesh-smack and then the red stamp on Thello’s cheek. Yorick can phantom-feel the sting on his own. Their mother is trembling. Yorick’s heart is pounding so fast. Everything can go wrong in an instant.

“I took it,” Yorick lies. “I wanted to play the netgames. I hid it under the bed.”

She doesn’t seem to hear him, but when he reaches cautiously for the tablet she lets it go. Yorick sets it screen-first on the floor, then stomps hard, eliciting a bone-deep crack. Thello flinches. There are tears winding down his face, but when Yorick insists with his eyes, his brother comes over. Thello stomps down on the tablet, first hesitant, then with a growing ferocity.

The smartglass crunches and squeals, a small symphony that blends with his sobs. Yorick monitors their mother’s face until she turns stiffly away.

Sleep doesn’t come. His eyelids scrape. His bones ache. Every cell in his body is exhausted. But as the skid churns closer and closer to its destination, more and more memories come for him, chewing through the walls of the sleepstack. The last of the endorphins from his phedrine shot have crawled away on all fours. He feels unwell.

When he gets the wake-up chime, when he pulls himself out of the sleepstack, he feels like a ghost of a ghost. No time to attach the mandible. He’ll do it at the hotel, with better hygiene. He taps the spot between his shoulder blades, and once his rucksack has climbed aboard he joins the crowd shuffling off the skid. Some are knuckling their eyes. Some reach for vapor pipes.

The stillness is eerie now that the skid has finally stopped. There’s a hollow in Yorick’s skull, the absence of a humming engine, as he heads down the ramp. The bay is lit by yellow pylons that jaundice the faces of the disembarking passengers. They’re at the bottom of a massive downtube; when he cranes his head he can see the top sealing shut, a shrinking black pinhole.

His skin pebbles as he passes the magnetic clamp that holds the skid in place. Enormous mechanical puppets with dripping proboscises whir to life around the chassis, checking, refueling, scraping away the accumulated ice. A melting lump smacks the back of his neck and trickles down the nape of his coat, soaking into the spiderwool.

He barely twitches. His nervous system is running on fumes, feet dragging on his way to the security queue. The main skid terminal is dreamy familiar: coppery skeletal architecture, oxygen recyclers belching vapor, vaulted ceiling cloaked with schedule holos. The time display ticks forward, but for Yorick it feels like time is running in reverse.

There’s no facelock up here, only a haggard man with a scanner wand and tablet. He’s pure sealie, the dominant geneprint in the north: jagged cheekbones, pale skin, big black eyes to filter the gloom. Yorick used to wonder why the other children could see so much better than him in the dark. He didn’t catch up to them until he joined the company and had his eyes peeled, standard mod for nocturnal operations—which was all of them on Ymir.

Yorick reaches the front of the queue. The man opens his mouth, to tell him to pull his coat down, then shuts it again as a notification flits across his screen. He gives Yorick a familiar twice-over, trying to judge him an offworlder or a cold-blood.

For once, Yorick is glad to be small for his geneprint, to have eyes with too much iris. The man judges wrong, and nods him through without a word. Yorick shuffles on. There was a wide scatter of accents and babeltalk aboard the skid, but now he hears the northern lilt emerging from conversations all around him.

Most of the conversations are about the grendel in the Polar Seven. Whenever a grendel makes itself known, so too do the fabulists. A person in a holomask is explaining how they saw a live one on Thoth, big as a frostswimmer, void-black hide and gnashing blue teeth that glowed in the dark. Yorick is too sleepsick to be amused.

He steps outside and sees a flash of busy street, twisty bioorganic structures rising from mist, a wrong-seeming sky. He inhales.

Mistake. The husk-dry air in the skid was filtered. So was the air in the terminal. The Cut’s air is a soup of old grease, dirty fuel, human urination, and Yorick’s first breath smashes nausea through his abdomen.

He thought his stomach would be safely empty after a few months in torpor, but when it heaves he sta. . .

When it sinks into the frost-coated docking cradle, the heat of its stabilizers turns ice to vapor. A thunderhead of steam slams out in all directions. The bowlship groans and shudders and finally comes to rest. It opens itself to the tunnels below, where automated laborers and exoskelled dockhands await to begin unloading.

Past the alloy stores, past the hydrogen tanks, in the darkest gut of the ship: the torpor pool. Bodies churn in a slow current around the reactor, tangling and untangling, a drifting mass of frosty flesh. They are skeletal, emaciated from the long haul, and their skins are coated a slick milky white by the stasis fluid. They are clinically dead, but not legally corpses.

At the far end of the pool, a door folds open. Two dockhands step through in a gush of steam. One is carrying a long hooked pole on her shoulder. A tiny drone is clinging to the end.

“Rerouted the whole ship for one fucking body,” she says. “Must be a company man.”

“We giving him a private thaw, then?”

“Sending him straight north. They’ll thaw him on the way.”

The drone darts ahead of them, fairylike on gossamer rotors. Its scarlet laser plays over the drifting bodies. The dockhands wait while a spiny walkway assembles itself, sprouting from the reddish-brown wall to extend across the torpor pool. They trudge forward, footsteps echoing in the cathedralic space.

The drone slides under the surface of the pool with a muted gurgle. The dockhands follow its red light, and the one with the pole slings it off her shoulder. She eases it into the stasis fluid, poking between bodies until the magnetic hook finds a particular harness.

Together, the dockhands dredge their catch up out of the pool. The walkway grows a socket to hold the base of the pole. It slides inside with a rasp and click, and the man is hoisted into the air like a puppet, dripping fluid. The dockhands peer at him.

He’s small, pallid-skinned and dark-haired. He has no lower jaw: between the blue curve of his upper lip and the rippled flesh of his throat there is nothing but medical membrane.

“Ugly fucker,” the first dockhand says. She points to a geometric spiral on his neck, the biotech tattoo the drone scanned to identify him. “Company man, though. I was right.”

“Looks a bit like you.” The other dockhand blinks. “Sending him north, you said? Maybe he a cold-blood, then. A cold-blood company man.”

“No such thing.”

But when they load the body into a drifting sarcophagus for transport, she sees shins and feet cratered with scars. Her black eyes widen, then narrow, and then she spits. It trickles down the side of the man’s frozen face.

“What’s that about, then?”

She stares down at the body. “No such thing as a cold-blood company man,” she says. “Only traitors.”

“So I was right.” He smirks. “Them cold-blood geneprints are real distinct. Sealie, yeah?”

“Half, maybe. Half-blood.” She hinges the sarcophagus shut. “Company’s mad to send him north. He’ll be leaving in a spraybag.”

They guide the body across the dark walkway, over the torpor pool, following the dancing drone.

Yorick wakes up dead, which is never comfortable. His chest is a clamp, lungs frozen, no heartbeat. His limbs are phantom. The hindbrain panic swallows him whole. He knows nothing except that he is alone and terrified and in the dark; every sensory-starved nerve in his body is screaming it, and then—

A jolt of electricity digs its teeth in, and his heart stutters back into motion. He owns his chest muscles again, so he sucks down a breath, ballooning all the crumpled alveoli in his lungs. The first one always feels like sucking back broken glass. A rehearsed thought comes to him: Nothing is wrong. You’re coming out of torpor. Nothing is wrong. You’re coming out of torpor.

He gasps. Bucks. Waits for the firestorm in his nervous system to subside, for the world to stop lurching from side to side. He works on proprioception, finding his body in space. His arms and legs are spread-eagled, punctured in a dozen places by tubes that are pumping him full of newly brewed blood. A diagnostic droid is scuttling up and down his torso.

His prosthetic mandible is missing. Cold dry air rasps in his wound.

“Welcome back from the River Styx, Yorick.”

Yorick’s eyes are crusted over. He works his lids until he manages to free one from the gound. First he sees only a dark gray haze. Next he sees an orange blur, flickering through his field of vision too quickly to track. He knows from experience that this is the orange suit of a thaw technician.

“It’s been a long time since we spoke last,” the voice says. “Nearly two decades here. Half that for you, I believe, with all the time spent in torpor. I can see you’ve done good work in that span. Eight successful hunts. Do they ever permit you to keep trophies from them?”

Yorick knows the voice. His gut coils tight.

“I still think you did your very best work right here with me, of course,” the voice continues. “Back in those early days of Subjugation.”

The tattoo on his neck prickles. He knows the voice, but it was one he never thought he would hear again, and if he’s hearing it again it means—

“I’m afraid this thaw’s not taking place on Munin. You were rerouted in transit to solve a more pressing problem here on Ymir.”

No.

No, no, fucking no.

“That seems to have spiked your adrenals, Yorick. Thrilled to be home, I expect.”

Memories crash in. Phosphorescent flares lighting up the ice field, the skull-pulping sound of smart mines going off. An anonymous body shredded to pieces, steaming, another barely intact, wriggling through the snow and slicking blood behind. And the owner of the voice is there, too, one bony hand on his shoulder, saying civilization costs.

“I’m an administrator here now,” Gausta says, voice sintered with faint surprise, as if she’s still marveling at the fact. “Living just to the east of your old haunts, overseeing security for all of Ymir’s northern-hemisphere extraction and refinery sites. Which brings us to why you’re here.”

Yorick wants to rage, to beg, to say that he will go anywhere, absolutely anywhere. Just not Ymir, the slushball of piss on the edge of the colony maps, the birthplace he swore to never set foot on again. But he can’t speak without his mandible. He only manages an animal groan that startles the thaw technician.

“Eight days ago a xenotech incident suspended all labor in the Polar Seven Mine,” Gausta continues. “There were grendels here after all, and we finally dug far enough to wake one up.”

Yorick isn’t afraid of the grendel. He’s killed the grendel a dozen times on a dozen worlds; it’s the job the company trained him for. He’s afraid of everything else.

“It butchered a few miners and then disappeared, as a grendel is wont to do,” Gausta says. “But the attack has reinvigorated anti-company sentiment here in the north. There are rumors of a strike. Fainter rumors of insurrection. We tread on thin ice.”

Yorick finally pries his other eye open. The orange blob of the technician sharpens. Above it, he sees the hazy outline of a holo projected on a low plaster ceiling. He can’t make out Dam Gausta’s features, but he recognizes the predatory angles of her body. He remembers her in a chamsuit, her long limbs dissolving into the ashy snow behind her, her hooded head turning dark as the starless sky. Before that, in a bright yellow coat.

“The algorithm balked when I chose you for this job, Yorick,” Gausta says. “You were only the third-nearest option, and the differential in transit cost was significant.”

Yorick forces the memories down and works on focusing his eyes. Gausta’s face comes clear, the wolfish gaze and jutting bones and swirled vitiligo skin. She’s aged less than he has in twice the years, as perfect and awful as ever, the gengineered telomeres of a company higher-up at work. Her eyes are unchanged, the same silvery pits.

“But machine minds are so limited when it comes to sociohistorical context.” Gausta gives her scalpel smile. “You understand this place, Yorick. Every day the mine remains shut and the grendel roams free, not only does the company bleed profit, but the locals’ discontent festers. Stability degrades.”

But it will never be stable up here; Yorick wants to scream it at her. The first colonists to come to Ymir were exiles and radicals. The generations born after were shaped by the cold and the dark into paranoid tribalists. He left because he didn’t want to die, and now the company has returned him with a tattoo on his neck, a target on his back.

Gausta reads his ruined face, or more likely his jolting heartbeat. “It’s been twenty years here,” she says. “And you’ve undergone quite a spectacular rendering of flesh. Nobody will recognize you, Yorick. So long as you do your work quickly, and tread lightly on the ice.”

Gausta leaves, but her avatar lingers to give Yorick logistics:

He will have one day to recover from torpor before he conducts his initial investigation of the site, accompanied by the Polar Seven’s interim overseer. His pseudonym will be Oxo Bellica, to avoid Yorick Metu’s lingering notoriety. His hunting equipment was not transferred, but will be reprinted pending ansible clearance. His clothing and mandible are nearly finished. He is three hours out from Reconciliation.

That last part jags him, but explains why the world has not stopped lurching from side to side. They loaded him straight from his bowlship onto the only passenger skid that heads north. Nobody in the north would ever call it Reconciliation, of course. It’s the Cut to them, was the Cut before the company ever arrived.

Unless things have changed in the past twenty years—Yorick considers that faint possibility as the thaw technician retracts the tubes, freeing him from his plastic web. They’re gentle with the flap of scar tissue and reconstructed flesh where his jaw should be.

“I can give you one more wake-up shot,” they say, muffled by their mask. “Nod if you want it.”

Yorick has been working mostly on clenching and unclenching his toes, wriggling his fingers, but he manages to bob his head up and down. Microneedles prick his neck, and a half second later he feels a chemical cloudburst, stimulants flooding his whole body. It rubs his nerves raw and makes him momentarily want to vomit.

The bed folds, easing him upright, and the diagnostic droid crawls off him.

“You ready to try walking?” the technician asks.

Yorick nods.

The technician nods at a chugging printer at the end of the compartment. “We’ll go to that printer. Get you your clothes and your prosthesis.”

Yorick grunts. He draws a deep breath, rubs the knotted muscles in his thighs. He holds the thaw technician’s shoulder as he takes his first shaky step, timing it to the sway of the skid. He takes a second. A third. On the fourth his knees buckle, his head rushes, and he nearly takes the technician to the floor with him.

“Today’s not going to be pleasant for you,” they mutter. “Thawing you this fast, yanking you straight off the freighter without calibrating your chemicals.”

Yorick shrugs his bony shoulders, gives the technician his own hideous version of a smile. He was not expecting a pleasant day anyway.

They stand him in front of the printer nozzle, just long enough for a patchy gray undersuit of spiderwool, then help him into his high-collared coat. The color is wrong, black instead of canary yellow, but it fits the same on every world. The boots are heated this time. He puts them on while he watches the printer work. It disgorges his rucksack next, a fabric shell that scuttles along on four stubby pneumatic limbs.

“Your prosthesis should be inside,” the technician says. “Do you want my help with it?”

Yorick shakes his head, because attaching the mandible is something he does himself, alone.

“Okay.” The technician scratches under their mask. “I’m getting off at Sants. I recommend you stay in here and rest. You’re going to be sleepsick for a while. Fatigue, nausea, some body dissociation. Probably hit the peak in four or five hours.” Their eyes flick to the tattoo on Yorick’s neck, then away. “But you can do whatever you like. Your vitals cleared threshold.”

A door dilates at the back of the compartment, and Yorick catches a brief glimpse of rocking corridor as the technician departs. He smells a whiff of dust and machine oil. Then he is alone with himself. He needs to rectify that quickly, so he rubs his thumb and pinkie together to beckon the rucksack.

It ambles over to him, sliding slightly with the motion of the skid, and peels open to display the exact same things as always. This is a comfort to him. Whatever world he wakes up on, the small orderly one inside the rucksack is unchanged. Basic black tablet. Coiled neurocable. Disinfectant brush. Microneedle injector. Rolls of gelflesh.

His mandible is in a slab of clear putty, still warm from the printer. He worms his hand past it, to the bottom of the rucksack, and finds the drug canisters. Immunosuppressors for his wound, phedrine for his mood—neutered company stuff, of course, not street-grade. But right now, even company phedrine will do.

He loads his injector with trembly fingers. When the microneedles punch through his capillaries it feels almost like sunshine. It’s the closest he will get to it on Ymir.

Yorick watches through the window as the skid churns along, throwing up a shroud of shattered ice in their wake. The sky is a black hole, all traces of starshine concealed by dense cloud. The only illumination comes from the skid’s running lights, a sickly green glow, the bioluminescence of some eyeless creature gliding along the primordial seafloor.

They’ve already passed the cities, passed the graveyard of one-way ships that brought Ymir’s first settlers and are still being digested for salvage a century later. They’ve passed the petrified forests and the airfarms that replaced them. This far north, the entire world is a single sheet of wind-scoured ice.

Yorick spots a herd of frostskimmers in the distance, leaping and gliding, attracted by the light of the skid. He observes them for a moment, then lets his phedrine high pull him farther along the swaying corridor. He hardly even minds that he is on Ymir, that he is heading north, that he is going to die there. His whole body is full of warm helium. He has the mandible tucked up under one armpit. His vague goal is finding the lavatory pod, where he will attach it.

The skid was noisy earlier, echoing with drunken shouts and laughter, a crowd of miners and a few fat-hunters swilling foamy bacterial beer in the corridor. Yorick kept his coat zipped to hide his lower face as he passed them by, but nobody glanced, too preoccupied by a wager: a tall bulky offworlder with an eye implant had bet they could contort themselves to fit in a standard-size sleepstack, claimed they were all cartilage, nephew, skeletal mod.

Now the corridor is dark, lumes dimmed by consensus, and half the skid’s passengers have shelved themselves into the miniature mausoleum to rest, not to win wagers. Yorick suspects they are trying to sync for the same work rotation. He keeps his footfalls soft, trying to outquiet the rucksack padding silently behind him.

There’s another window before the lavatory pod, and through it Yorick sees the one interruption to Ymir’s cold horizon. It grows in the distance, a warped mound erupting from the ice, sheathed in nanocarbon scaffolding and coated in buzzing drones. As always, it’s difficult to judge the size of it. Even veiled in human tech, the original architecture of the ansible has a disorientating effect. Workers take a certain depressant drug to mitigate it.

A memory flashes through Yorick’s head, neural sheet lightning: trekking out to the ansible when he was fourteen, maybe fifteen, clambering over the blockade, seeing who could creep closest before the nausea and the brain-bend were too much to handle. He remembers the alien structure as an enormous face, carved from black rock, sutured with eerie blue lights.

It’s the ansible that drew the first colonists here, the ansible that marks Ymir as one of the Oldies’ abandoned worlds. The company took it over during Subjugation, and Yorick doubts anyone clambers over the blockade anymore. Not if they want to keep their skulls intact.

He feels unease trickle, icy, through his phedrine high. Partly for the memories, which he knows will only get worse the longer he’s here. Partly because passing the ansible means they are barely an hour from the Cut. He knows this journey, this skid north, from what he thought was his very last day on Ymir. That day ended very badly.

Someone is puking in the lavatory pod. Muted sounds, throat and splash. Yorick’s shrunken stomach gives a sympathetic ripple. He goes the other way, finds a vacant sleepstack. He peels down his coat just long enough for it to scan his company tattoo, then climbs inside.

The concrete cube of the apartment. Yorick and Thello are small, crouched on the floor, playing with rubbery yellow dolls they got from the toy printer. One is an exoskelled soldier holding a tiny howler. The other is a monster, a mass of spines and tendrils.

Their mother looms over them. “Where’d this come from, then?”

Her anger is a pressure drop; Yorick feels his chest tightening, his ears ringing. She doesn’t mean the toys. She means the tablet dangling from her hand, the basic black square that the company men were giving away last week near the junk recyclers. She holds it casually, asks the question calmly, but Yorick can hear the needles underneath.

“Didn’t steal it,” Thello says. “Swear truth. It was for free.”

“What did they tell you it’s for?” their mother asks. The needles are sharpening. Yorick knows, instinctively, that it would have been better if Thello had stolen it.

“You can go on the net with it,” Thello says, face flickering confusion. “Play. Learn things.”

“Learn things from the company,” their mother says, snarling the last word. “The Cut existed before they showed up. You learn that?”

Thello shakes his head, gledges pleadingly at Yorick. Yorick ignores him. Thello deserves this, for hiding it under the gelbed instead of in the spot behind the cooker.

“It was just smaller, that’s all. Simpler.” Their mother runs her frayed nail across the tablet’s surface. “Just a chasm in the ice, deep enough to wait out the blizzards. Then we find the first vein of zinc, and suddenly the company wants to make friends.”

“Nothing like that,” Thello mumbles. “Learned about the Oldies, about the grendels—”

“So they come with buildbots, with bubblefabs, with air,” their mother interrupts. “With gene scanners, credit, implants, and contracts. With smiles here.” She drags a corner of her mouth upward with one finger. “And knives behind their backs.”

Yorick has heard these words, or similar ones, a hundred times. He knows to nod and keep his mouth shut.

“They’re not our friends.” She holds out the tablet to Thello. “Smash it.”

Thello, stupid little Thello, flushing and defiant, shakes his head. Yorick wants to hiss in his ear: you can get another one, it doesn’t matter, just smash it.

“Or I will,” their mother says, raising the tablet high.

Thello’s eyes dart left. He shakes his head again, and this time he mutters something, too. “Our da, though. Our da was a company man. Everyone says.”

Her free hand snaps out; there’s the loud flesh-smack and then the red stamp on Thello’s cheek. Yorick can phantom-feel the sting on his own. Their mother is trembling. Yorick’s heart is pounding so fast. Everything can go wrong in an instant.

“I took it,” Yorick lies. “I wanted to play the netgames. I hid it under the bed.”

She doesn’t seem to hear him, but when he reaches cautiously for the tablet she lets it go. Yorick sets it screen-first on the floor, then stomps hard, eliciting a bone-deep crack. Thello flinches. There are tears winding down his face, but when Yorick insists with his eyes, his brother comes over. Thello stomps down on the tablet, first hesitant, then with a growing ferocity.

The smartglass crunches and squeals, a small symphony that blends with his sobs. Yorick monitors their mother’s face until she turns stiffly away.

Sleep doesn’t come. His eyelids scrape. His bones ache. Every cell in his body is exhausted. But as the skid churns closer and closer to its destination, more and more memories come for him, chewing through the walls of the sleepstack. The last of the endorphins from his phedrine shot have crawled away on all fours. He feels unwell.

When he gets the wake-up chime, when he pulls himself out of the sleepstack, he feels like a ghost of a ghost. No time to attach the mandible. He’ll do it at the hotel, with better hygiene. He taps the spot between his shoulder blades, and once his rucksack has climbed aboard he joins the crowd shuffling off the skid. Some are knuckling their eyes. Some reach for vapor pipes.

The stillness is eerie now that the skid has finally stopped. There’s a hollow in Yorick’s skull, the absence of a humming engine, as he heads down the ramp. The bay is lit by yellow pylons that jaundice the faces of the disembarking passengers. They’re at the bottom of a massive downtube; when he cranes his head he can see the top sealing shut, a shrinking black pinhole.

His skin pebbles as he passes the magnetic clamp that holds the skid in place. Enormous mechanical puppets with dripping proboscises whir to life around the chassis, checking, refueling, scraping away the accumulated ice. A melting lump smacks the back of his neck and trickles down the nape of his coat, soaking into the spiderwool.

He barely twitches. His nervous system is running on fumes, feet dragging on his way to the security queue. The main skid terminal is dreamy familiar: coppery skeletal architecture, oxygen recyclers belching vapor, vaulted ceiling cloaked with schedule holos. The time display ticks forward, but for Yorick it feels like time is running in reverse.

There’s no facelock up here, only a haggard man with a scanner wand and tablet. He’s pure sealie, the dominant geneprint in the north: jagged cheekbones, pale skin, big black eyes to filter the gloom. Yorick used to wonder why the other children could see so much better than him in the dark. He didn’t catch up to them until he joined the company and had his eyes peeled, standard mod for nocturnal operations—which was all of them on Ymir.

Yorick reaches the front of the queue. The man opens his mouth, to tell him to pull his coat down, then shuts it again as a notification flits across his screen. He gives Yorick a familiar twice-over, trying to judge him an offworlder or a cold-blood.

For once, Yorick is glad to be small for his geneprint, to have eyes with too much iris. The man judges wrong, and nods him through without a word. Yorick shuffles on. There was a wide scatter of accents and babeltalk aboard the skid, but now he hears the northern lilt emerging from conversations all around him.

Most of the conversations are about the grendel in the Polar Seven. Whenever a grendel makes itself known, so too do the fabulists. A person in a holomask is explaining how they saw a live one on Thoth, big as a frostswimmer, void-black hide and gnashing blue teeth that glowed in the dark. Yorick is too sleepsick to be amused.

He steps outside and sees a flash of busy street, twisty bioorganic structures rising from mist, a wrong-seeming sky. He inhales.

Mistake. The husk-dry air in the skid was filtered. So was the air in the terminal. The Cut’s air is a soup of old grease, dirty fuel, human urination, and Yorick’s first breath smashes nausea through his abdomen.

He thought his stomach would be safely empty after a few months in torpor, but when it heaves he sta. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved