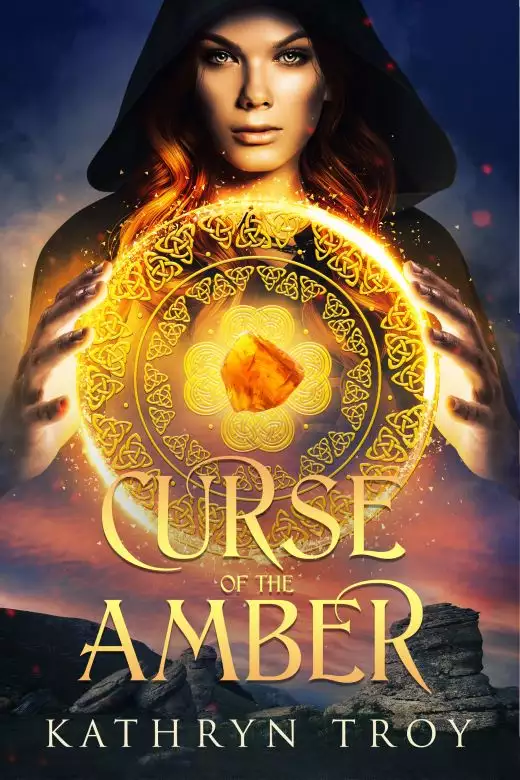

CURSE OF THE AMBER

ASENATH

Chapter 1

The sun seems to have forgotten Wales. I didn’t think there was any place on Earth that could make me long to be in Egypt again, but I couldn’t escape the memories that flooded me. I shivered in the absence of the Valley’s merciless heat, where for summers on end its oppressive dryness sucked the life out of my lips and baked my skin into hardened, sand-beaten clay. That dryness had followed Ramesses, Amenhotep, Aken-aten, and his son beyond the world’s suffering down to their resting place, and kept the divine kings ready in the dark, empty stillness.

But the day’s oppression had always faded with the sun. The perfection of those nights on the Eastern Bank, at our host Hani’s home—that was what I missed. Invigorated by the fresh, life-giving breeze off the Nile’s surface and snuggled between my parents under thin woven blankets was a warmth I knew I would never feel again. The cold and damp of Britain, once the stronghold of the Druids, was relentless. The gnawing feeling at the pit of my stomach grew, and the thought I’d pushed away more than once made itself more insistent.

This was a mistake. I shouldn’t be here.

My fingertips numbed to the statuette in my hand, a solid representation of the wet chill in the air. Its faceless form was as alien to me as the bog in which I crouched. The shape of the stone fetish was at least interesting, a long, slender column with a severe “V” etched into it. It held more promise than the dozens of thin rings fashioned out of iron, bronze, and even gold, heaped together in a tangle, the clay pottery, now in shards, and scraps of linen that appeared to be tossed desperately into the bog as a last-ditch effort to avoid Roman destruction. But I couldn’t enjoy it for what it was. It was inscrutable, too disconnected from anything familiar. Its primitive, obscure expression reminded me of my own cold thoughts, and as I squeezed the chilled stone in my hand, I doubted if I would discover anything that had once been warm—made of flesh and blood. We were as deep down as the famous bog bodies had been, more so in certain places, and still we had nothing, or rather no one, to show for it.

I lifted my head, trying to shake off my melancholy and averting my eyes from the stone carving that would not reveal its secrets to me. I was too low down to inhale even a whiff of air that wasn’t saturated with the grassy pungency of the bog wall. From my vantage point, huddled low in a deep, man-hewn pit, the sodden depression of the bog appeared even more overgrown on all sides. Birch trees poked out of humble clusters of willows, red-speckled buckthorn, and mountain ash. Except for these trees skirting its outermost edges, the sunken area was wide and open. The cauldron bog retained its secluded atmosphere, despite being carved into a series of waterlogged cavities.

My somber mood deepened when I saw my advisor approach. Up until then I’d been successful at avoiding him. I deliberately didn’t linger, and always found a reason to visit another pit when the one we were in suddenly emptied of other researchers. I’d resisted the wrenching feeling in my gut too long, but as our excavation wound down, it was impossible to ignore, with nowhere for my thoughts to hide—there was nothing left of what used to be my life.

“How’s it going?” Alex asked, and knelt beside me.

“Fine,” I answered, not bothering to look up from the peat I was brushing off of a link of iron rings sunken into the over-saturated soil.

After a long, awkward silence, he said, “It’s okay, you know.”

“What is?”

“If you don’t…if we don’t find one.”

I swallowed hard. The only place for my rising fury to go was back down.

“I just don’t want you to think that this whole thing was a waste—”

“A waste?” I shot back. “I’ve got enough to keep me occupied for the next decade, thank you.” It was true, but that didn’t make the prospect of studying human sacrifice sans a human sound any better. Nothing would tell us as much about the Druids as human remains that had, willingly or otherwise, undergone their practices. It may have been more than anyone else expected, but the bar had been set impossibly high. A human discovery might have been the only way to exceed my father’s own discoveries in the Valley of the Kings and earn the same level of respect in my own right.

“All right, all right,” Alex said, contrite. “I didn’t come over here to upset you.”

“Then why are you here?” There was more bite in my voice than I meant, but he had that amused eyebrow raised again, the one that made my anger meaningless and painted me as a silly, wide-eyed novice with dreams of finding the next Tut.

“I thought you might need a refill.” He offered me a cup of coffee.

A gruff “thank you” was all I could manage. My brain had reached maximum capacity for caffeine, but it went down easy. Milk and two sugars, just the way I liked it. Damn.

He reached out for me but caught himself before his fingers could find their way into my hair, frowning before he lowered his voice.

“Will you come tonight, Asenath? It’d be a shame for you not to see the room. You picked it, after all.”

Memories of Alex’s firm, feverish grip on my hips, his moans in my ear, passed unbidden across my mind. Some days it was so easy to look at him and just see the charming, somewhat quiet young man always at my father’s side, more often than not covered in two-thousand-year-old dust.

“Will you tell her?” I asked.

His silence hit me like a stab in the gut. It was self-inflicted—those rosy pictures and all his stale promises were just a veil, a childhood infatuation. I saw him then as he was—his chocolate-brown hair had dulled, the sharp line of his chin softened; so had the brilliance of his eyes, their dark fathoms fading. Small lines crept at the corners of his eyes and mouth. I bit my tongue as a distraction. The imprints of his touch on my skin would fade, if I let them.

I sipped my coffee again. It had a bitter taste the second time around. When I let the silence settle between us, he rose to his feet, stifling a groan on the way up. He disappeared again to the other side of the dig, and I went back to work.

I ended the day uploading my latest round of pictures as usual. Dr. Pryce, the head of the Aarhaus team, walked into the makeshift tent and took up the seat beside me.

“Good evening, Miss Hayes.”

“Hi, Dr. Pryce. I’m almost done here.”

He nodded. “Time for your daily report. Carew was preoccupied, so he asked me to come in his stead.”

“Preoccupied with what?” I asked, then mentally kicked myself the moment the words escaped my mouth. It was too familiar, but my patience with Alex was thin. Dr. Pryce didn’t seem to notice, and only smiled, a sly thing with a hint of amusement. “Right,” I answered, shaking my head. “Well, according to today’s soil readings, we’re anywhere from fifteen to twenty-five hundred years down, and some of the wells were definitely dug by human hands.”

“Wells,” Pryce repeated, bobbing his head thoughtfully, “but no mounds.”

“That’s right.” I felt my face flush hot under the electric lamps swinging overhead. The Druids hadn’t built permanent structures, making them an elusive lot. But I’d hypothesized that impermanent markers, made of dirt and mud, had been either destroyed or overlooked completely. The clunky peat-cutting that locals relied on for fuel had raised almost every bog body ever found by sheer accident. Any significant difference to the topography would have been ripped apart before anyone had realized its importance. I had at least hoped to map out some pattern to the ritualized deaths bog bodies had endured and give more substance to Julius Caesar’s accounts of human sacrifice among the Druids. But without markers in the ground as a reference, or actual victims to study, deciphering the meaning of these haphazard bits and bobs wouldn’t amount to a whole lot that we hadn’t known before.

I think Pryce read the disappointment on my face, and tactfully changed the subject. “It’s taking us longer than we thought to hit our marks,” he said. “It’s unlikely that we’ll be able to complete the site, this time around at least.”

I blew air out of my lips in a loud puff, deflated. He’d caught me. I had tried not to be concerned by it, but we were behind schedule. Cerriglyn Bog couldn’t support the weight of bulldozers. The ground was too unstable. We’d been left to do the grunt work with smaller machines, sometimes only by hand. It made just reaching our intended depth a daunting task. I pursed my lips and wondered if I would ever feel the African sun on my face again, or see Hani’s familiar, wizened face. He was probably still there, giving respite to obnoxious tourists, those he decried for destroying his homeland with their discarded water bottles and used-up film canisters. A hollow feeling deepened in my chest at the thought, threatening to swallow me up. I did my best to shake it off.

“Let’s narrow the field, then,” I finally answered.

Dr. Pryce smirked and pulled a copy of our working map from his back pocket. “I thought you might say that.”

“Am I that predicable?” I asked.

“Predictable? No. But capable? Yes, you are that, Miss Hayes. So, what do you think?”

I examined the map centered around Cerriglyn Bog. Bordering its northeastern edge was the forest, with fainter lines indicating its prehistoric boundaries intersecting the topmost sectors of the bog. Along that corner crawled a small creek. Minus the geographic features, the map was blank. Staring at it was like gaping into an abyss, and that overwhelming feeling crept back up again, settling in my armpits and down the center of my back. I hoped Pryce couldn’t smell my fear.

I closed my eyes, wishing for the meticulously plotted charts of the Valley of the Kings, its pristine, orderly rows and markers instead of this yawning nothingness. But it too, once, had been only a mass of nondescript, transient dunes. I looked at the map again, the one in my mind’s eye laid over it like a transparency. The bog beneath came to life, reacting like watercolor paper dipped in ink. Invisible markers blossomed in neat, ordered lines, woven together by unseen pathways into a modest village, one as close to the wetlands as safety would allow.

“Let’s pull it in here,” I said, pointing to the northeastern sector where the environmental markers overlapped—where the bog met the forest and where it touched the bank of the creek. “Take half your team out of the south and move them to the center.” Those in-between spaces would have been the most sought after, the ones deemed sacred. If we didn’t find anything bigger than chicken bones there, I doubted we would find them anywhere.

“Will do,” he said, restoring the map to his pocket. “You know, Miss Hayes, I never really thanked you for thinking of us. This is the most exciting thing that’s happened to our department in decades.”

“Of course,” I answered quickly. “You’re right here. I thought it would be wrong not to. Although I’ll admit that my intentions were not entirely altruistic—your Celts might be able to tell me something that the pyramids can’t.” That was the main reason I’d gone along with Alex’s suggestion in the first place—I was seduced by the idea of bringing Druidism out of the shadows and drawing a line straight back to the practices that made pharaohs divine kings and praised wetlands as sacred.

Pryce smiled. “You are your father’s daughter, Miss Hayes.”

I turned my face from him and bit my lip. The sting of tears that should have run dry long ago tried to push its way forward again. I tried to console myself with the thought that, had I not already been thinking about them, it wouldn’t have hit me as hard. But even I wasn’t convinced.

Pryce cleared his throat. “I apologize, Miss Hayes. I—”

“It’s fine,” I assured him, blinking to clear my eyes. “Thank you for the compliment.”

“I’d ask you to stay longer, if I didn’t think Alex would have a fit. Lord knows he wouldn’t get any work done without you.” He rose from his chair and left me with a knowing grin.

***

Pryce’s parting words left me wondering just how much Alex was supposed to be doing as my supervisor. I shifted restlessly in a moldy dorm bed, abandoned in the nadir of the academic year. Today was not the first time that Alex was seen to shirk his duty. Sneaking breaks and doing his utmost to not tire himself out as much as the next man was second nature to him. It stung to have my work, my conclusions, be subject to his opinion. But it was too late to switch advisors and explaining the more pressing reason for wanting the distance was out of the question.

In the starkness of the brisk night, my boots called to me. Their plush lining was irresistible at the ridiculously late hour. I’d never get any sleep if I didn’t clear my head and at least try to keep warm. I pulled the barely upholstered desk chair next to the window. After pushing down on the window to confirm that, yes, in fact, the wind was coming through the closed frame, I set the chair in front of the window, so that the frame sat at the leftmost corner of my vision, leaving the rest of my view looking out onto the bog which lay in the distance. Thick grasses and clusters of myrtle clutched each other in the darkness, shivering violently in the wind. Moonlight bounced off their tangled, indefinable edges, and the more I peered into the Welsh countryside, the more it divested itself of its false bluntness. The bog and its surrounding brush revealed whispers of greens, blues, purples, and yellows in its multi-layered blackness. Calm crept softly over my frazzled brain as I roughed out the scene before me in charcoals, paying attention to the angles and proportions before treating its colors and textures. I willingly lost myself in the quick strikes of my hand against the paper. Thoughts of anything but how to render the window frame fell from my mind. I considered whether to keep the aged, peeling texture of the white frame intact, or to restore it to a gleaming pristineness set at odds with the watery chaos beyond. As I worked, the untarnished frame looked too unnatural, so I weathered it once more. I worked until my eyes became blissfully heavy and drifted down into sleep.

I was still working on the image of the bog in my dreams. My charcoal strokes had become bloated with water, bleeding my greens, my blues, my whites, and my blacks together until the bog was nothing but a dark mass, a bottomless chasm. Obsidian waves shifted and swayed—something was rising to the surface. I couldn’t run, couldn’t scream or blink the image away as the rising wave took shape and glided across the surface of the bog. A shrunken, wrinkled face emerged from the watery depths. Its twisted mouth wrenched open to reveal a blank expanse. Vacant eyes glowed an unearthly blue, staring straight into my soul.

I woke gasping for air and wiped a sheen of cold sweat from my forehead. Raindrops pattered onto the floor beneath the window, its brittle borders unable to keep either wind or water out. The edge of my picture, laid on the nightstand, was visible out of the corner of my eye. The rain glistening on the windowpane reflected on the paper in the moonlight, making the colors look blurry and wet—alive, almost. I was afraid to turn my head, afraid in the way that you can be only after waking suddenly, still too tied to your dreams to know they aren’t real. Those glowing, luminescent eyes still stared at me, through me, at the edge of my mind. I held my breath and looked. The only things on the paper were what I had put there—high grasses peering into the window frame, that crumbling barrier against the creeping dark without. It was splintered and cracked, losing its power to keep the fen at bay.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved