- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

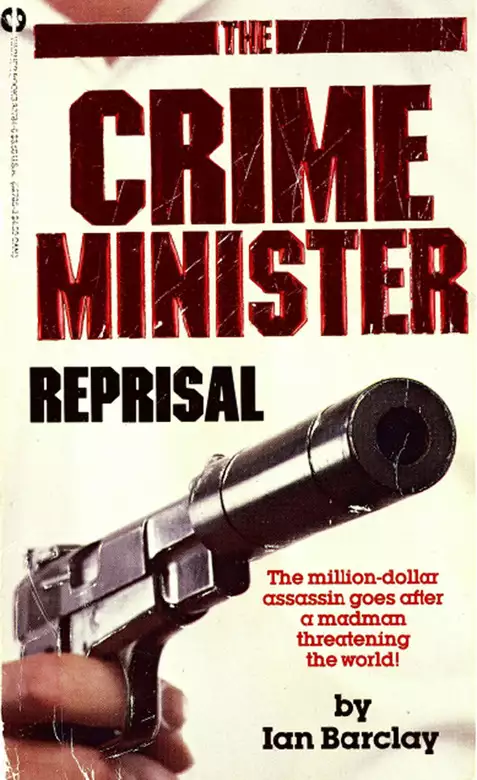

Synopsis

When Ahmed Hasan, a religious fanatic with nuclear technology in his power, takes over the Egyptian government and poses a deadly threat to the turbulent Middle East, professional assassin Richard Dartley is hired to destroy him.

Release date: December 19, 2009

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 192

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

CRIME MINISTER: REPRISAL

Ian Barclay

window of their home for him to button his coat. She said it in French, so her eight-year-old immediately obeyed. Here in

France he had taken to ignoring her when she spoke to him in Arabic or English. The family had never spoken French back in

Egypt. Her husband was fluent in the language, and her son was already speaking in the local accent and using slang. Only

she continued to have difficulties, and she knew that she was an embarrassment to her son before his friends here, a foreigner

so barbaric she did not appreciate their precious language.

The previous day her husband received another of the phone calls at his lab in the Centre d’Etudes Nucleaires. It was a different

voice this time, but again the man spoke in English with a strong Egyptian accent. They were to be made an example of, so

that

others equally reluctant to perform their patriotic duty might learn from their mistake.

When the Light of Islam fundamentalists suddenly overthrew the Mubarak government in Cairo, her husband happened to be at

a conference in Brussels on the peaceful uses of atomic energy. An Egyptian civil servant at that time, almost a year ago,

her husband had added his vacation to the conference and taken her and their son with him to Brussels. They had been lucky

to be away. Her father and one of her husband’s brothers had been killed in the bloodlettings and purges after the takeover.

They would never go back. Both of them felt this way. No matter what they were offered to return. No matter how they were

threatened…

Because of the phone call, she had walked the boy to school and picked him up in the afternoon. Now she was keeping a close

eye on him as he played with a neighbor’s dog in front of the house. She was cleaning the windows, shivering because she was

unaccustomed to the raw October wind of northern Europe.

She noticed a black car pass the house. She couldn’t tell one make of car from another, and she only looked because they had

so little traffic on that road in the town of Saclay. The car seemed to slow a little in front of the house, and the driver

glanced in and caught her eye for a moment before moving on. There was another man next to him in the front seat.

It was the same car a few minutes later, black, two men in the front seat—although this time the driver was on the side farthest

from her since they were coming from the other direction.

The car was not traveling fast, and the driver deliberately swung the front in, so that its side was almost scraping the low

wall of the tiny garden in front of the house. Her son turned and ran before it like a small frightened rabbit.

The front of the car struck him in the back and lifted him into the air. His light frail body smashed against the windshield,

rolled rapidly across the roof, and dropped on the road in the wake of the car.

She dropped her cloth, leaped through the open window into a flower bed, and ran to the garden gate, which was ajar. She was

screaming.

Before she reached the gate, the black car was backing up. The man next to the driver had his head out the window and was

shouting instructions in Egyptian.

The rear wheel crossed over the child’s body. The boy’s head and shoulders were beneath the vehicle. His sneakers kicked as

the tire sank a narrow lane across his chest.

“It’s getting late, lieutenant,” the gendarme said to Laforque. “You’d better go now if you want to see the body.”

Laforque had a bony face and wore a dirty trenchcoat. No more than in his mid-thirties, he already looked soured on life.

He said, “Any reason I need to?”

“No,” the gendarme said. “I usually try to avoid dead kids myself when I get the chance.”

The gendarme was at least fifteen years older than his superior officer and was not afraid to have his say.

The two plainclothesmen went to a bar and ordered Ricards.

“Maybe you think it was a waste of your time, lieutenant, having to leave Paris to come down here—”

“No, I don’t.” Laforque had forgotten the gendarme’s name. “If they had listened to you in the first place, that scientist

might never have caused all this fuss.”

The gendarme was pleased. “I put in the call as soon as I heard what the child’s father had to say about threats being made

against them, especially because they were Arabs. I don’t mind our Arabs, like the Algerians and Syrians. But the Egyptians weren’t ours. Why didn’t they go to England and bring their troubles

there?”

“Because this Egyptian is an important nuclear scientist,” Laforque said.

“Well, they have nuclear stuff in England too,” the gendarme grumbled, lighting an unfiltered Gitane. “I still say they should

have gone there and let us alone.”

Laforque was undecided. So far Paris had handled things badly, and he didn’t want to make bad worse by overreacting. The gendarme

had acted professionally. As soon as the boy’s parents had made the claim their son was murdered, he had notified Paris on

an emergency basis. When no response came, the Egyptian pair drove into Paris themselves and somehow managed to interest Dutch

television in their story. Government-run French TV had no choice but to pick up the story too. Which meant that what the

Egyptian pair claimed had to be taken seriously. Like the gendarme said, because they were Arabs.

Lieutenant Laforque was liaison officer between the Gendarmerie Nationale HQ and its counterterrorist unit GIGN (Groupement

d’Intervention de la Gendarmerie Nationale). GIGN was primarily an HRU (hostage rescue unit) and had sprung more than two

hundred and fifty captives in its ten years’ existence. But the unit was also on call as a SWAT team, unlike most HRUs in

other countries. Every man in GIGN passed tests in endurance, swimming, running while laden with equipment, marksmanship,

martial arts… fought full-contact karate with Black Belt instructors, warded off attack-trained dogs, attended parachute jump

school at Pau and high-speed driver training at Le Mans… rappelled down the side of a highrise building, holding the rope

in one hand and a pistol in the other, shooting at designated targets while coming down fast. GIGN’s best known mission had

been their rescue of a busload of French schoolchildren seized by terrorists on the border of Somalia.

Laforque had graduated from this school of hard knocks with a bullet lodged next to his spine. He had been taken off the active

list and been given a commission. Lieutenant. If he behaved and made no big mistakes, one day he might make captain. He said

nothing, but others remarked that he seemed less than thrilled at this prospect. It was rumored he had been recruited by one

of the intelligence services.

The gendarme next to him in the bar knew none of this. To him Laforque was just another of those deskbound pen pushers from

HQ who got irritable when asked to visit the outskirts of the city.

The lieutenant made up his mind. “I can’t put a GIGN team on the house as things presently stand.

We don’t even know if the pair will return here tonight. They may stay in Paris. Last I heard of them, they were on their

way to see German and English reporters. They may be in New York by now, for all I know.”

“Their child is in the morgue here,” the gendarme said flatly. “They’ll be back to bury him.”

“You’re right. I know that the initial medical examination backs up the mother’s story of the car first hitting the child

and then backing up to deliberately run over him, so we’re probably not dealing with a hysterical story. I know that the parents

may be in danger. But you have to understand that I can’t call in a GIGN unit here and then tell the men to go hide in the

bushes. There has to be a… a situation first. Someone for them to fight.”

“I understand, m’sieu.”

Laforque bought two more drinks. “All right, so I’m dumping on you. I’ve got no other choice.” He made a smudge of water on

the plastic counter. “Say that’s Paris. Here we are in Saclay, to the southwest. Here’s GIGN in Maisons-Alfort, to the southeast,

maybe twenty kilometers away. Any sign of trouble, call this number I’m giving you and“—his index finger traced an inverted

semicircle beneath the smudge representing Paris—“this place will be overrun in no time. I’ll put in an alert. Can we depend

on you to watch the house tonight?”

The gendarme nodded grumpily, making it plain he thought this was not how things should be done.

Laforque glanced at his wristwatch. “Got to go.” He left a tip on the counter, shook hands, and took long strides out the

door.

The gendarme surveyed the tip, decided it was too much and ordered another Ricard from it.

When the couple got back shortly after eleven that night, the gendarme got out of his car and stood in their headlights in

order to reassure them.

“For a moment, we wondered who it might be parked outside the house,” the man said.

“You were right to be cautious, sir,” the gendarme said, peering in their car window, feeling that he was breathing the fear

they gave off like a poison gas. “No need to worry. I’ll be sitting in this car out here all night.”

The gendarme had no plans to ambush terrorists or behave like a hero. He had placed his battered Citroen in a highly visible

position directly in front of the two-story house. He sat behind the wheel and smoked cigarettes. Every half hour he got out

and walked up and down the empty road beneath a single street lamp. The last lighted windows, in a house down the road, went

dark sometime after one. The gendarme sighed and settled down to a long slow watch. What he disliked about all-night surveillance

was how it raised gloomy thoughts in his mind, gave him time to brood, to go over wrongs done to him and all his disappointments.

He could feel this despondent mood coming on and did not look forward to his own company during the long night.

A little after three he thought he noticed a movement in the garden to one side of the house. A shadow… for an instant. He

could not be sure.

He stayed where he was in the car, looking intently at the place. He saw nothing further. Having slipped

the door handle quietly, he eased out of the Citroen, his pistol in his right hand, a flashlight in his left coat pocket.

The gendarme sat on the garden wall, raised his legs over it and stood again inside. The only sound as he moved forward into

the dark was that of rose thorns catching the fabric of his pants leg.

Two figures behind the house—definitely!

“Stop!”

The gendarme fired. They disappeared.

He did not turn on the flashlight, not wanting to make himself an easy target. He stared into the dark, motionless, looking

for any more signs of movement. Sticks snapped a distance back in the trees, as if someone stood on them. A window lit upstairs

and placed an elongated rectangle of pale light on the ground in back of the house. The couple had been woken by his pistol

shot; if they had ever managed to sleep.

Just then he noticed that a ground floor window was open. They had been inside!

“Come down quickly,” the gendarme shouted up at the lighted window. “Come as you are. Fast.”

He was still shouting when his words were drowned out by a roaring flash inside the house. The gendarme knew immediately what

it was—an incendiary device, not explosives. He went in the open window and saw the staircase was in a sea of flames. The

heat was intense, and the old timbers crackled like fireworks as the building started to burn. Dense smoke billowed everywhere,

choking and blinding him.

Why hadn’t they come to an upstairs window and jumped? Perhaps they had while he was inside the

house searching for them. To see if he could get upstairs that way, he forged through the dense smoke into the front room,

keeping his face next to the wall when he took a breath to make use of the thin layer of untainted air that always lay between

smoke and a surface. He saw her on the floor of the room, lying facedown.

When he reached her, he saw her husband was lying not far away. They must have come downstairs just before the incendiary

went off and been knocked unconscious by its force. A wall had protected them from being burned.

The gendarme slumped the woman over his right shoulder in a fireman’s lift which kept his left hand free. He made for one

of the closed windows in the room, then thought better of it. A window opened at this stage could feed the blaze a jet of

oxygen which could explode the house in a fireball. He made his way back to the window he had enteted in the back of the house,

guessing he would never have time to come back for the man.

By the time he climbed through the window with his burden, laid her on the ground a safe distance from the house and returned,

the whole interior of the ground floor was a raging inferno. He ran to the front of the house to see if he could get in a

window there, but the room where he had found the woman was bright with flames. Her husband would be dead already.

She was on her feet when he got back, moving unsteadily and saying something over and over again in Arabic.

“I’m sorry, madame, I could not reach your husband. It was too late.”

She stared at him as if he had said something so obscene to her she did not know how to react.

He went on gently, “We can’t do anything now. I will take you into town where you will be looked after.”

“My child! My husband!” she shouted in French and rushed toward the flaming house.

The gendarme caught up with her and stopped her from leaping through the fragmented glass of a window into the furnacelike

interior.

“I want to die! Kill me! Let me die!” She beat desperately on his head with her small fists as he carried her, struggling,

to the Citroen.

Keegan looked up from his desk at the State Department in Washington, D.C., and nodded to the Secret Service agent who entered

his office.

“You’re bright and early today, sir,” the agent said.

“Early, but not so bright. It’s never good news that brings me in early.”

The agent went directly to the telephone scrambler in one corner of the office. The KYX scrambler was a big metal box, and

the combination lock in its front made it look like a safe. The Secret Service man unlocked it and replaced an IBM punched

card in it with a new one bearing the day’s code. He left without another word.

Keegan glance at the off-green telephone connected by wires to the scrambler. It was only 7:30 A.M. The call from Paris was not due for another hour. He went back to his paperwork.

The call came through on time.

“Paris embassy. That you, John? Is the line safe?”

“Go ahead, Christmas Tree,” Keegan said.

“Same shit today, John. Things as they stand now are like this: We’ve intercepted messages from the Israelis making open threats

to the French of destroying the nuclear reactors the French are building in Egypt. The French seem to care only about the

insolence of the threats, although they did put a mildly worded question to the Egytians on whether they might be making an

atom bomb. The Egyptians, of course, denied it, and claimed that if the Zionist entity bombed their peaceful reactors, they’d

launch missiles from the Sinai onto Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. The Israelis intercepted that message and told the French they

were ready to nuke Cairo. All it would take was one Egyptian missile on Israeli soil and it was ashes-to-ashes and dust-to-dust.

You following me?”

“Loud and clear, Christmas Tree,” Keegan said, although the voice at the other end of the line sounded as if it were coming

through a long tube. “You think they’d do it?”

“If you were in Cairo, would you order a missile to hit Tel Aviv?”

“No. But then I’m not a fundamentalist, Christian or Islamic. Tell me more, Christmas Tree.”

“Big news is the French have continued to pull out their experts from Egypt. I’m pretty sure it’s in direct reply to Washington’s

accusation of Paris being responsible for nuclear proliferation. When you people said equipment and fuel supplies might be

effected, the French began to hear what you were saying. The Egyptians are trying to lure back their own technicians

who fled when the mullahs took over, but so far they don’t seem to be succeeding. Enough of the French technicians have left

already to slow things down considerably. You might put this forcibly to the Israelis as a reason for them to delay any strike

they might have in mind against the Egyptian reactors.”

They went on to talk of other things.

The AirEgypt turboprop cargo plane touched down on the runway at Cairo International Airport. Two army Range Rovers waited

at the cargo terminal, and an officer and four soldiers watched the ground crew set up to unload the aircraft. The temperature

was in the high sixties, a sunny, pleasant October day, after a scorching summer that had made the asphalt runways and air

laced with jet fuel fumes a more hellish place than any to be found in the Libyan Desert.

The officer climbed the ramp and pointed out two plywood crates, each about four feet square, marked London-Cairo/Al-Qahira

with red serial numbers. He double-checked the numbers against those on a clipboard and shouted at the workers to handle the

crates carefully because they contained sensitive, high explosives. The soldiers laughed and the workers grinned nervously.

They set the crates down gently on a small flatbed wagon attached to a miniature tractor, which towed them into a customs

shed cordoned off by ropes. Paper signs dangling from the ropes read in Arabic and English: MILITARY INSTALLATION—KEEP OUT. The soldiers lifted the crates from the wagon and waited for the driver to leave the shed before they set about

tearing open the crates. A bald man in civilian clothes took a stethoscope from his jacket pocket.

Inside the first crate were huddled a woman and a boy about five. The soldiers stretched them on their backs on the concrete

floor. The doctor kneeled over each of them in turn to listen to their breathing, feel their pulse, lift an eyelid, look inside

the mouth and place the stethoscope on the chest. He grunted and moved on to the next pair, two girls about seven and nine,

obviously sisters.

When he rose to his feet, the doctor gave the officer a severe look. “I don’t think much of this method. These people are

fortunate to be alive. They should come out from under the effects of the drug in five hours or so. They’ll be feeling groggy

and nauseous for a while after that. Whose idea was this?”

The officer raised his eyes to the ceiling. “Not the Army’s.”

“I thought not. Well, you can tell whoever did think it up that, in my professional opinion—”

The officer gestured to the doctor to lower his voice and led him out of earshot of the four soldiers.

A cold drizzle fell on Cambridgeshire. The small, spare Egyptian physicist made his way through the centuries-old quadrangles

of Cambridge University without a coat, seemingly heedless of the weather. He drew an occasional amused glance from students,

who dismissed him as an absentminded prof for whom a raw October day was merely meteorological data.

But Dr. Mustafa Bakkush was not absentminded or

eccentric. He was in the middle of an emotional crisis so violent he was oblivious to his rain-soaked shirt, jacket and pants.

He walked through deep puddles among the paving stones without seeing them or feeling the water spill into his shoes.

When he reached the research building, he walked past his lab door and on down the corridor to the director’s office. Ponsonby

was sitting behind his desk in his white lab coat, shaking his head slowly at a plastic model of a nuclear structure.

“We’ve got it wrong somewhere, Mustafa,” he said without looking up, “and I’m damned if I know where.”

Mustafa Bakkush was not deflected from his purpose. “Gordon, I want to resign. Immediately.”

Gordon Ponsonby’s eyebrows shot up. “Dammit, man, you just got here. You can’t walk out on us like that.”

“I have to.” Mustafa sat on the edge of an upright chair, small, wet, cold, miserable.

Ponsonby stared at him. “Been on a bender, old boy? You look like something the cat brought in.”

“Gordon, they tell me I’ve got to go.”

“For God’s sake, who? Buck up, man. Out with it. Those bloody Americans? They have no money for physics these days—don’t believe

a word they tell you. The Germans?”

“Home. Egypt.”

Ponsonby was flabbergasted. “But the mullahs denounced you personally as a decadent Westerner. Who knows what would have happened

if you and your family hadn’t reached our embassy in time? And remember the fuss we had to smuggle you all out?

Now, hardly a year later, you walk into my office, looking as if you stopped to immerse yourself in the river on the way,

and announce you want to go back. Homesick for the pyramids, I suppose.”

“Gordon, I don’t want to go back. I have to. They have Aziza and the children.”

Bakkush told the director of the phone calls he had been receiving, culminating in the disappearance of his wife and children

four days previously.

“You didn’t go to the police?”

“The man on the telephone warned me not to. He said they would not be harmed if I kept quiet. I knew he was an Egyptian and

not an ordinary criminal. This morning I received a phone call a little after five. He gave me a Cairo number and told me

to phone it. It took more than an hour to get through. I asked for Aziza. She came to the phone and told me they were all

safe and well. They allowed her to tell me what happened. Men came to the house with two crates. They put them in the garage,

saying they were scientific equipment I had ordered. She could see they were Egyptian, and they explained that by saying I

had contacted them because they were fellow countrymen and needed the work. They managed to delay until all the children were

in the house, then they chloroformed everyone with a cloth over their faces. After that they must have injected them with

a powerful drug and put them in the crates. Aziza overheard one man say they had been shipped out of Gatwick on a cargo plane.”

“Gatwick! Good God, what’s Britain coming to!”

“Much as I dread going back there, for Aziza and the children’s sakes I have to.”

“Yes, yes, of course you must. What rotten luck. We’ll keep the journals open to you and expect to see you at conventions

and so forth….”

Mustafa shook his head. “I won’t be working on the cutting edge of physics when I go back to Egypt, Gordon. They have a program

I suspect they need me for, one that’s become past history in more technically advanced countries.”

Ponsonby averted his eyes. “When do you leave?”

“Tomorrow.”

“Good luck.”

There was nothing more to say. After Bakkush left his office, Ponsonby pressed the intercom to his secretary in an alcove

farther down the corridor. “Mrs. Arthurs, I have to go to London today. What time’s the next train?”

He held the phone in his left hand, and with his right removed a cassette from the tape deck concealed beneath a desk drawer.

John Keegan sat in. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...