- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

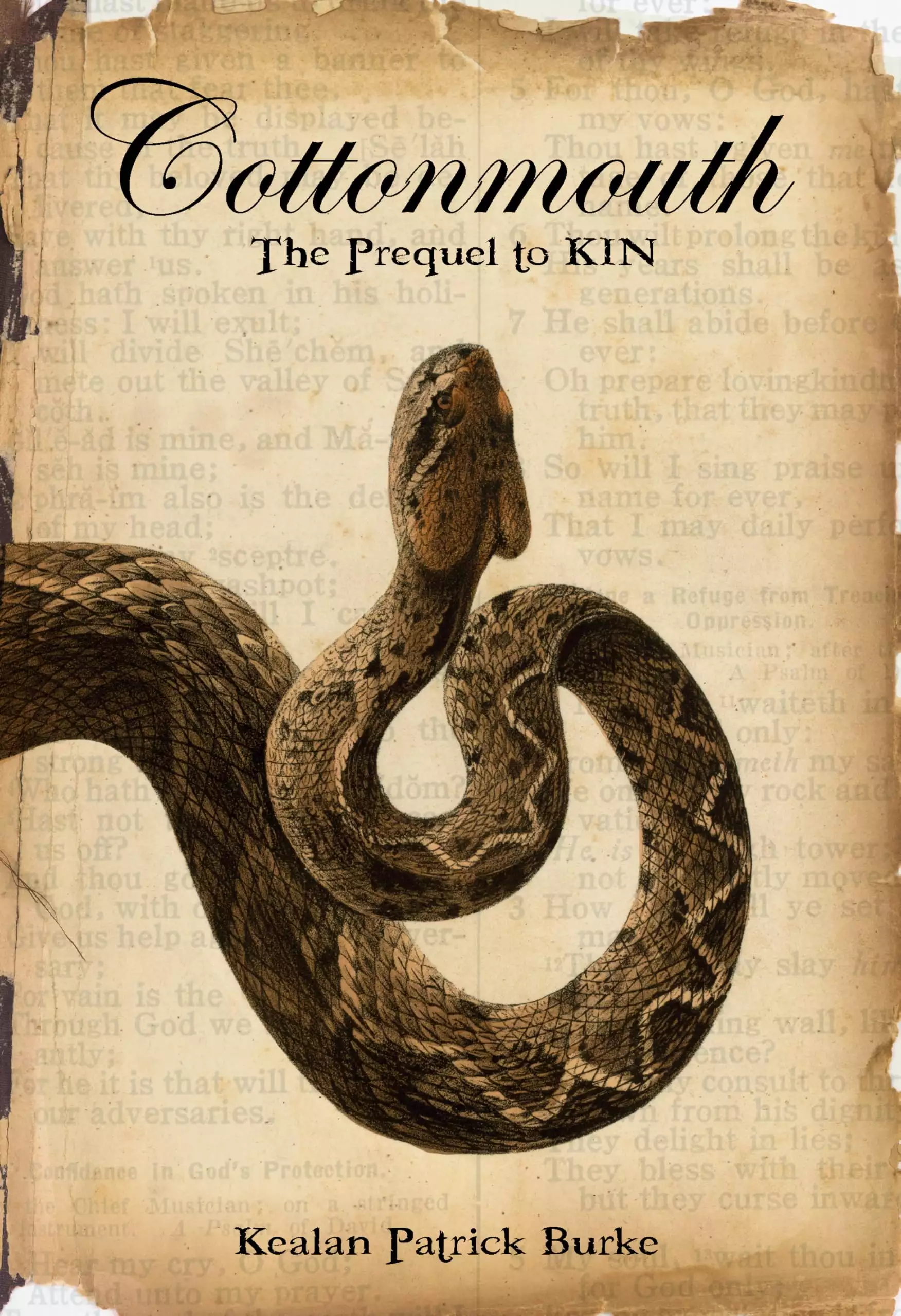

Synopsis

Available for the first time in paperback and digital.

A thrilling prequel to Kealan Patrick Burke's southern gothic horror novel Kin, COTTONMOUTH is set in the aftermath of the Great Depression in Tennessee, a time of religious fervor and charlatanism, of thieves, murderers, and moonshiners.Here you'll meet Horseshoe Collins, a traveler on a vengeful search for the father who abandoned him; Billy Wray, a snake-handling Pentecostal preacher bringing the promise of salvation to rural communities paralyzed by fear of the Devil; and Jonah Merrill, a child grieving the loss of his beloved father and tormented by his mother's wrath.

With the threat of a second World War looming on the horizon, destiny will bring these three people together and set innocent young Jonah on the path to his eventual fate and a new name: Papa-In-Gray, the patriarch of the dreaded Merrill family whose horrific exploits were first introduced to the world in KIN.

Release date: June 13, 2025

Publisher: Elderlemon Press

Print pages: 166

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Cottonmouth

Kealan Patrick Burke

Chet Collins had not always been a wanderer, nor a philosopher, but an almost fatal kick from an ill-tempered mare in the spring of 1931, on the cusp of his twenty-first birthday, changed him forever. Always a jovial, quick-witted, and kind fellow, the injury altered him in ways that did not sit well with the people around him. Gone was the congenial youth with the broad smile and warm eyes, subsumed by an interloper given to strange ideas and impromptu soliloquies on subjects that made little sense to anyone but himself. People began to avoid him, their wariness graduating from pity to mockery. Over time, hungry for a more receptive audience for his ideas and driven by a single impulse to find the man whose shadow he could not escape, Chet responded by removing himself from the sight of all who knew him.

If he’d ever had a real home, he struggled to remember it, though sometimes in daydreams the face of a woman rose in his mind, and he remembered her as a benevolent presence in his life. She might have been his mother, and consequently he thought he might miss her, though this was a feeling enforced by the frequency of her appearance in his dreams, and thus, did not qualify as a legitimate emotional connection.

Liberated, he took to the blank page of the open road, his body the pen with which he intended to write the story of his new life, a story that started with his new name, Horseshoe, to match the large C-shaped indentation on the right side of his head and face, the scar a pink path where the hair around his temple and the stubble on his chin would never again grow.

The Ballad of Horseshoe Collins. The resonance of the title pleased him.

Sometimes, with the stub of a pencil, he wrote his thoughts into a battered old notebook he had, in his previous life, used to copy down passages from the Bible. Those excerpts filled the first sixteen pages of the journal, and often he considered tearing them out, for they might as well have been written in another language for all they meant to him.

“Why do you look so strange?” a little girl asked him once, startling him from his reverie. He’d soon be rousted by the owner, but for a few moments, he was happy sitting on the bench outside the grocery store in another in a long line of towns whose names would disappear as soon as he left it behind.

“Well now,” he said, cheerfully, trying not to smile, for he had learned that his old injury had mottled the appeal of that once benevolent expression. “Twas a horse what did it.”

The little girl studied him, face blank and eyes dull. To her young mind, he was an idle curiosity, nothing more. He watched as her gaze took in features that were unbalanced, his right eye slightly lower than the left, the corner of his mouth turned up on that side so that he always appeared to be smirking. The folds and ridges of his ear had been smashed flat. In silhouette, the indentation looked deep enough to collect rainwater.

Her analysis done, the little girl delivered her verdict. “You’re awful ugly.”

Then she walked away. A little boy about her age burst from the grocery store giggling and together they ran up the street. They were soon followed by a tired looking man with heavy shoulders and dark circles under his eyes, who seemed annoyed to find the children nowhere in sight. Their father, Horseshoe assumed, and hailed the man.

“They run off up the street,” he offered.

The father looked him up and down, forgetting to temper his disgust, and wordlessly followed the children up the street.

“Coulda said thanks,” Horseshoe muttered to himself, but in truth he was not surprised by the absence of civility. It was everywhere now, the disrespect of the adults inevitably filtering down to their children. The world was getting meaner. It didn’t help that his physical characteristics made him look threatening, when Horseshoe believed himself nothing of the kind. He did not wish anyone harm, though as his travels went on, he found goodwill was not a currency accepted in all

quarters.

He killed his first man in January of the next year, a situation he wished could have been avoided and often still lamented, but for reasons that remained a mystery to him, there existed in the dark corners of the world people dedicated to hate and violence, implacable creatures immune to tact or kindness or deference. Often while mulling over the incident and the different ways in which it could have played out, Horseshoe would conclude that some people simply wanted to die and thus were drawn to the blade as if it were a totem of salvation, or mercy.

Horseshoe had had no quarrel with the man he’d slain. He’d been minding his own business that night, warming himself by a small fire under a railway bridge. Horseshoe had been keeping the flames low so as not to draw undue attention to himself when the stranger slid down the frozen embankment behind him. Horseshoe looked back over his shoulder and greeted the man, ostensibly to ensure him he was not a threat. The stranger did not seem similarly inclined. “Got something to eat?”

Horseshoe looked apologetically at the can of beans and meager strips of bacon fat sizzling in a small tin pan over the fire. “Slim pickins, brother.”

“That’ll do,” the stranger said, and closed the distance between them to hunker down by the fire. Before Horseshoe could open his mouth to object, the man’s large dirty hands were in the pan, plucking up the bacon scraps and dredging them through the beans, his enormous shadow rising up behind him to darken the wooden supports of the bridge.

“Not sure I invited you to help yourself, friend,” Horseshoe said, both offended by the man’s presumptuousness and saddened that he’d found himself in the company of someone so ill-mannered after a long hard day on the wintry road. His cold feet ached, the soles of his cheap shoes worn thin. Ice had rained from the sky for most of the afternoon, and the beans and bacon were his first bite to eat in a day and a half. And now here was this brute come from God knows where, scooping up the last of the hard-earned food as if it he had every right.

“Hear what I said?”

Using the last curl of fried bacon fat to scoop up what remained of the beans, the stranger popped the food into his mouth, gulped

it down, belched, and then looked squarely at his host. Horseshoe had never seen such dead eyes on a man before. It chilled him. “I heard, but it don’t matter now, do it?”

“I expect you’ll be movin’ on then,” Horseshoe said, caution rendering it a suggestion, not a command.

Still fixing those dead-carp eyes on him, the stranger shrugged. “Expect I might stay here a while where it’s nice’n warm.”

“Nothin’ stoppin’ you from makin’ a fire of your own.”

“Nothin’ stoppin’ you from shuttin’ the fuck up, neither, yet you keep talkin’.”

To his own surprise, Horseshoe felt a sudden surge of acidic heat inside him that clenched his jaw and set his muscles twitching. He wanted to lunge for the stranger, maybe ram the tin pan down his throat or use his battered old spoon to scoop out his lightless eyes.

He wanted very much to do this, if only to punish the man for his rudeness, but that hardly seemed justification enough, so he tempered the anger and forced a smile on his face.

“Fair enough,” he said. “Can’t rightly send you out in the cold.”

Nonplussed by the gesture, the stranger continued to stare into the fire, hands raised, palms presented to the flames. His large face was grubby, the creases around his eyes and mouth blackened with grime. A deep jagged scar ran from the right side of his chin up across the bridge of his nose through his left eyebrow and up his forehead to disappear into the hem of his ragged woolen cap. It was as if someone had tried to bisect the meat of his face into two rough pieces. Had the stranger been a friendlier sort, the scarring might have evoked in Horseshoe an affinity or some sense of camaraderie for a fellow sufferer, but all he saw now was a bully, and a potential threat. He did not relish the thought of a sleepless night, but that’s what a smart man needed to do if he intended to see the sunrise.

“You from around?” he asked, hoping a little conversation might help pass the time, as much as it galled him to entertain his loathsome visitor.

“I am,” the stranger replied.

“I do, but what’s it to you to know it?”

“So’s I know the company I’m sharin’, I guess.”

The stranger frowned at him, and the scrutiny felt to Horseshoe as if the man had his hands inside him, stirring his guts around. “Ain’t nobody sharin’ no company here. Got it? If I was to run you off right now, you’d do it, so if you thinkin’ you’re the one doin’ favors, think again.”

“Well, my name’s Horseshoe.”

“Dumb fuckin’ name for a dumb fuckin’ cunt, I reckon.”

“No need for that kinda talk, friend.”

“I ain’t your friend.”

“You had my food and you’re sharin’ my fire. What are you if not a friend?”

“Someone who could kill you soon’s look at you’n I’ve already looked at you twice, much as it pains my fuckin’ eyes to do it.”

Horseshoe raised his hands in surrender and went back to watching the fire, but the acid was worse now, cauterizing the base of his throat, flowing in molten currents through his veins.

If the stranger kept provoking him, he could not be sure where all this was going to lead, only that it was unlikely to end well for one of them. After a few months on the road, Horseshoe knew that vagrancy was dangerous and unpredictable. Strangers like these, men brought low by economic collapse, were everywhere, and would think nothing of gutting you in your sleep and taking what little you had. Regular joes wouldn’t blink at the loss of a pack of matches or a can of beans or a spoon or a knife, but to men of the road, these were the tools of survival, and thus, things to be coveted.

“I am curious, though,” said the stranger, shifting on his buttocks, eyes on the fire, one stubby finger pointed at his temple. “Horse kick you because you was tryin’ to fuck it or what?”

For a moment, Horseshoe could only look at him, but then the stranger’s face split into a wide grin, revealing he had only three teeth left in his mouth, all of them stained yellow and black. Horseshoe shook his head, bewildered by the man’s unfiltered audacity, but then a laugh bubbled out of him and in seconds, both men were bent dangerously close the fire, wracked with uncontrollable gales of laughter, tears streaming down their filthy faces. When the stranger regained control of himself, he wiped a clean path through the grime on his face, then held the hand out as if offering the dirt to Horseshoe. His shadow leapt and danced behind him. The sight of it made Horseshoe uneasy, as if a worse version of his unpleasant visitor was being born from the darkness under the bridge.

“You got any hooch in that little sack?” The way he asked made it clear if it wasn’t offered, he was going to take it, just like he’d taken the food.

Grateful to have a reason to look away from the man’s menacing shadow, Horseshoe nodded and reached into the knapsack he kept by his side, turning his body slightly out of habit so the stranger’s greedy eyes wouldn’t see its meager contents.

“What’s the little book for?”

“Collectin’ my thoughts.”

“Let’s see it.”

“I’d rather not.”

He could feel the man leaning close, trying to peer around him, and when he looked over his shoulder, the man was so close to the fire, it lent his face a devilish aspect.

“C’mon now,” the stranger said, eyes alive with delight.

To pacify him, and get his attention off the notebook, Horseshoe handed over what was left of the small bottle of cheap whiskey he’d bought from a guy at the trainyard a few miles back. Whiskey was illegal here, so such things were precious. He hated to part with it but would have hated more to have this man’s filthy eyes intruding upon his most secret thoughts.

The stranger snatched the bottle and studied it with a critical eye. “That all you got? Shit. This won’t last but a minute.” To demonstrate the truth of this, he unscrewed the cap, brought the bottle to his lips, and tilted the bottle back, perfectly exposing his unshaven throat to the razor in Horseshoe’s hand.

In one deft move, Horseshoe leaned forward and drew the blade across the flesh just above the man’s Adam’s apple, then sat back and waited.

“Fuck,” the stranger said, lowering the bottle and looking at Horseshoe with dull surprise.

He licked his lips and dropped the bottle, then brought both hands up to the thin red line only now forming at his throat. “D’you do that for?”

Blood trickled and spurted between his fingers as he squeezed. He began to look around, as if the imminence of death had reminded him of critical tasks that needed doing.

“Weren’t no need to be rude,” Horseshoe told him, genuinely hurt. He did not like what he had just done. Indeed, he wasn’t even aware he was going to do it until he saw the razor there next to the bottle, the pearl handle gleaming in the red light like a mystical thing. And perhaps it did have some kind of magic power. After all, he couldn’t recall where it had come from. He’d just woken up one morning to find it lying there next to his bedroll. Perhaps the thing was cursed and even now was guiding his hand, influencing him.

A rustle brought his eyes up to the stranger, who had toppled over on his side wearing a growing bib of blood. His eyes were still wide and unfocused, a terrible frightened mewl slipping from his mouth. “Momma,” he wept. “Jesus, Momma, please. I ain’t ready.” His legs moved, feet scrabbling against the frozen clay, as if he were trying to walk sideways into the fire. “Please Momma…”

Horseshoe had never killed a man before, so he didn’t know how long it was going to take before the stranger stopped talking. Minutes? Hours? What he did know is he didn’t want to listen to the guy pleading for his mother all night. It was terrible, it made him feel guilty, and he was dog-tired and ready to put this day behind him. He thought it only right that the stranger did the same. And since the dying stranger had stolen his food, it seemed only fair that he contribute something to the menu, something he wasn’t going to need, or miss. Something that would quieten him while he bled out on the cold ground.

“I’m sorry, fella,” he said, and meant it.

PART ONE

SHADOWS WITH NO ONE TO CAST THEM

I

Mayor’s Hollow, Monroe County

Tennessee

1936

Jonah’s mother liked to burn things. No matter the season, she would often be found in the mornings and late evenings staring into the flames that rose from the rusted burn barrel they used to dispose of their trash. Even when there was no waste to burn, she would gather sticks and branches from the surrounding woods and spend hours standing immobile, face slack, eyes watering from the smoke, hypnotized by the fire. The rust had gnawed holes in the body of the barrel and at night, the light flickering through them made a shadow theater of the close-knit pines, while sparks spun skyward to compete with the stars.

Jonah didn’t know why she did this, and dared never ask, for when his mother returned from her counsel with the fire, she often carried part of it within her, and sometimes he got burned. Her mourning had made her cruel, and as a child of adventure, Jonah inadvertently gave her reason to use the belt on him. Tracking mud through the house. Getting burrs on the sofa so ugly it already looked made of them. Being gone for too long. Most often, he gave her no reason at all and still she brought the leather to him, raising welts on skin ignorant of its transgressions. He had learned to let her be and make himself as small as possible, no easy task when the house was little more than a tumbledown shack with a tarpaper roof, the living area a single rectangular space divided by paper-thin walls into smaller rooms.

It started after his father died, crushed beneath an ancient pine up on Bracken Hill. Had it gone differently, had he moved a second earlier, he might only have lost an arm, but Jonah thought, given the choice, his father would have preferred death. He was a man who’d always taken great pleasure in his strength. The perception of weakness would have killed him as sure as that tree. It just would have taken longer.

The news was delivered by a tall, profusely bearded man by the name of Ronnie Dalton. Jonah had seen him around a few times. He’d come over on Friday nights to drink and play cards with his father.

“Hell of a thing,” he said, sitting at the kitchen table and supping from a pewter hip flask so scratched it looked like a picture of black rain on a grey day. “We was all mighty fond of your Thomas.”

Jonah’s mother sat opposite him, mouth open slightly, eyes like the windows of a vacant house. For all the response he got from her, Ronnie might as well have been sitting alone. Jonah watched them from the door until he got tired of listening to the man talking to himself, then retreated to his room—little more than a rickety bed and a flaccid pillow and the little wooden train his father had carved for him—and wept in silence. Then he prayed because his mother demanded it, though he often wondered why. She did not seem very godly, not since the tree came down on his old man, but if he forgot to pray or prayed without sufficient fervor, she’d appear at his door with that belt wrapped around her hand, her face drawn down by the gravity of pious anger.

Ronnie started coming around more often after breaking the news that Papa was dead. He was even at the funeral, the small crowd mostly made up of loggers who looked bored and eager to be on with their day, and a preacher with red eyes and a redder face, who read passages from the Bible with all the passion of a census taker. Jonah cried until his mother walked away from him, leaving him alone

at the open mouth of his father’s grave. The weather was warm and bright which struck Jonah as strange. It was supposed to rain when you buried someone you loved.

He looked down into the rectangular hole in the earth, at the lid of the cheap wooden coffin, and quietly begged his father to come back to him. It was not a plea he knew would be heeded, because Papa was with the angels now.

After the funeral, Ronnie walked home with Mama, leaving the boy to trail behind, confused by his anger at the God that had taken his father from him and his mother’s lack of attentiveness to his suffering.

Sometimes his mother spoke, but it was as if she’d forgotten most of her words. Ronnie didn’t seem to mind. He just kept talking about nothing for hours and hours, pulling from the flask to lubricate his lips. Sometimes he stayed for dinner, and every time, he sat a little closer to Jonah’s mother. It was like watching a series of photographs develop. And although the boy was not the most perceptive of children, he didn’t have to be to know that the man who smelled of sour milk, whiskey, and cigarettes, wanted more from his mother than she was willing to give. It was the way he looked at her through those hooded bloodshot eyes and how his hand always seemed to find her wrist, or her knee.

One night, Jonah woke to commotion, and, driven by fear for his mother’s safety—though no amount of imagination could paint her as a victim—ran out into the living area to find Ronnie hunched over by the front door, one palm pressed against his temple, fingers drenched with blood. A whiskey bottle lay shattered on the floor, the wood beneath soaked with however much liquor it had contained before whatever had happened to break it. Ronnie’s ordinarily narrowed eyes were wide and glassy with naked hostility.

“You…fuckin’…whore,” he said, each word carried on sharp but shallow breaths. He didn’t seem to register the boy’s presence, but this was nothing new. To Ronnie, Jonah was a ghost, because Jonah had nothing he wanted.

Mama stood on the other side of the rickety kitchen table where her wounded guest had once played cards with her dead husband. Her

face was blank as she went to the drawer beneath the sink, opened it, and withdrew the knife she had, back when she cooked, used to carve meat. It had a scuffed wooden handle, the blade dull enough to have earned the right to refuse the light. Wordlessly, she turned to face Ronnie, who was already backing up toward the door.

“I’ll be back,” he said. “Oh, you best believe I’ll be back, an’ when I come, that knife of yours won’t do you a damn bit of good. Mind me now.”

His mother said nothing, only watched, knife held up so her intent was clear.

“Goddamn crazy bitch,” Ronnie said, but the fight was already leaving him. “Everyone was right about you. Nuttier than a shithouse rat.”

And then, to the surprise of both man and boy, she spoke, and it had been so long since she’d last used her voice, it came out sounding like someone raking rocks from hard clay. “Best leave, Ronnie Hall, ’fore I start carvin’ slices off you.”

Eyes bulging with rage, he looked from her face to the blade, as if weighing the chances of getting at her before she stuck him. Though he eclipsed her in weight and height, something, perhaps her voice or the dead look in her eye, kept him from trying.

“This don’t end here. Hope you know that.”

She took a deep breath and slowly released it. She might have been watching the lazy turn of a river for all the emotion on her face.

“Set foot here again and you’ll wake to find me grinding your prick into cornmeal.”

Incredulous, for it was clear no woman had ever dared speak to him in such a way, Ronnie could only shake his head. “Fuckin’ loon,” he said. He spat a thick wad of phlegm on the floor, flung open the door, and disappeared into the night, leaving a chorus of crickets to eat the quiet.

“Momma?” Jonah said, afraid to go to her lest she forget who he was and turn the knife on him instead. The look in her eyes suggested it as a possibility.

After an unknown stretch of time in which mother and child stood immobile like figures in a painting, Jonah watching his mother, his mother watching the door, her breath escaping her nose in long soft hisses, she set the

knife down on the table.

“Go say your prayers. Pray for your father’s soul, and for a bad end for Ronnie Dalton. “

Then she went out to commune with the fire.

Things were better for a while after that. Ronnie didn’t come around again, but sometimes on one of his monthly trips to get provisions and sell rabbit meat and pelts, Jonah caught sight of him in town, stumbling from tavern to tavern, muttering hostile challenges at anyone unfortunate enough to stray into his eyeline. Jonah gave him a wide berth, sometimes hiding until he was sure the man was out of sight.

Three weeks later, Ronnie lost his right eye in a fight over a card game.

A week after that, he tried to avenge the theft of his eye and was beaten to death, his blood and brains leaking through the cracks in the wooden floor of Manahan’s Taphouse.

At home, Jonah’s mother continued her nightly rituals.

Always her fingers were black and grey from the soot, so much so that the townsfolk—if you could call Mayor’s Hollow a town, and most didn’t—had christened her Mama Ash. He would never know if she was aware of this moniker but didn’t think it would have bothered her much. It fit, because all knew her newfound affinity for the flame, and knew better than to question it. She was a widow now, and nobody questions the curious habits of the grieving, for grief is unbridled chaos, and chaos breeds odd habits. But all knew her as a God-fearing woman too, so they let her be.

II

In June of 1936, a stranger came to the house. Jonah was setting snares when the rumble of an engine drew his attention to the dirt road bisecting the woods upon which his father had built their house. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved