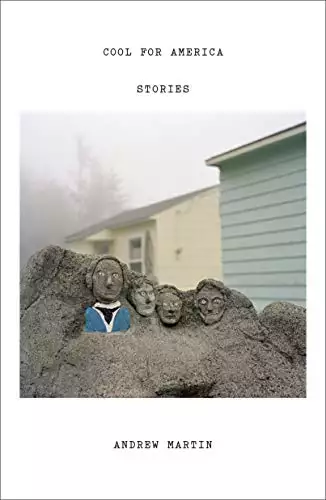

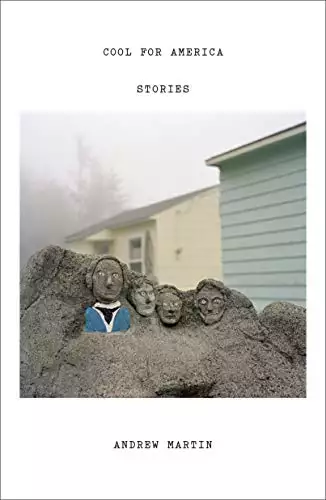

Cool for America

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Expanding the world of his classic-in-the-making debut novel Early Work, Andrew Martin’s Cool for America is a hilarious collection of overlapping stories that explores the dark zone between artistic ambition and its achievement

The collection is bookended by the misadventures of Leslie, a young woman (first introduced in Early Work) who moves from New York to Missoula, Montana to try to draw herself out of a lingering depression, and, over the course of the book, gains painful insight into herself through a series of intense friendships and relationships.

Other stories follow young men and women, alone and in couples, pushing hard against, and often crashing into, the limits of their abilities as writers and partners. In one story, two New Jersey siblings with substance-abuse problems relapse together on Christmas Eve; in another, a young couple tries to make sense of an increasingly unhinged veterinarian who seems to be tapping, deliberately or otherwise, into the unspoken troubles between them. In tales about characters as they age from punk shows and benders to book clubs and art museums, the promise of community acts—at least temporarily—as a stay against despair.

Running throughout Cool for America is the characters’ yearning for transcendence through art: the hope that, maybe, the perfect, or even just the good-enough sentence, can finally make things right.

Release date: July 7, 2020

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cool for America

Andrew Martin

The ants had gotten in through the shattered bottom half of Leslie’s laptop screen. Now they crawled across her green-and-blue-tinted Word documents and websites one or two at a time, with no discernible pattern or destination. It must have been a hell of a place for an ant, all that glowing landscape to be negotiated, possibly forever. It wasn’t clear whether any ants ever escaped or if they all just died in there. If they were dying, they at least had the decency to do it over in the dark border area of the screen or down in the keyboard, rather than within her line of sight. She was trying to see how long she could go without buying a new computer. The sound of crackling glass every time she opened the screen suggested that the reckoning was nigh.

She was on her front porch, trying to make herself write an email to her ex-boyfriend Marcus, who was, she had just learned, due back in town in a week for an exhibition of his drawings at a local gallery. (Well, exhibition, gallery—his work was being featured in the basement of the camera store in downtown Missoula.) She wanted to tell him that he shouldn’t be worried about running into her, that she no longer had any loose feelings about the breakup, that she thought it would be nice to have a drink, even, if he found himself with some time on his hands. But these thoughts wouldn’t form themselves into coherent sentences on the screen, maybe because she wasn’t sure they were true. She hadn’t forgotten the ugly melodrama of their final months together and she hadn’t forgiven him for going off to Italy for a fellowship without her, like a punk-ass. The worst thing about studying art history was the artists.

Her newish man, a mannish boy, was named Cal, for the baseball player, he claimed, though Cal Ripken would have only been a rookie when he was born, so it was probably made up, like Hillary being named after the Everest climber. Anyway, he was from Baltimore originally. Like many of the men she knew in Missoula, he was a dog trainer, novelist, and organic grocery store employee. His sweaters had moth holes in them. He rolled his own cigarettes. His novels weren’t self-published, technically, but only because one of his friends in town printed and distributed the books for him. His friend’s service fee was mostly offset by the handful of sales Cal made at his readings, which were attended with shrugging obligation by his friends and the town’s mostly elderly patrons of the arts. There was, in fact, a reading that night at Marlowe’s Books for his latest opus, a four-hundred-page novel set in Butte on New Year’s Eve, 1899.

It wasn’t ideal to date a bad—or, okay, flagrantly mediocre—writer, but it wasn’t as terrible as she’d worried it might be. Cal had decent, if very male, taste in books (Bolaño, Roth, David Foster Wallace) and wasn’t aggressively dumb about most things. He also, blessedly, lacked ambition; he didn’t seem too stressed out during the composition of his books, and he didn’t seem to worry about the fact that no one outside of Montana, and few people within it, would ever read them. He was smart enough not to push it, and that counted for something. And, frankly, she wasn’t in a great position to judge his work or his choices, given her own life situation (this being a polite euphemism for depressed and barely employed), but she did know what was good and what wasn’t. This hadn’t blossomed into an ethical dilemma yet. Politeness and desire and taste did not all have to be mutually exclusive, did they? And maybe it was his lack of anxiety about his literary status that made him so good in bed. Leave it to somebody else to pierce the human heart with punctuation.

She gave up on her email to Marcus for now. She picked up the laptop—one hand supporting the bottom, the other cradling the fragile spine—and went back into her apartment through the propped-open front door. She laid the computer on the couch gingerly and got a beer from the refrigerator, then drank it in the kitchen, staring out the window at the parking lot, thinking about Marcus.

* * *

She was five minutes late for her copyediting gig at the Open Door, and Lyle called her out for smelling like booze. But what was the point of working for an alternative paper if you were supposed to show up sober? She was told to start with the fourteen-page “community calendar” as punishment. “Join BodyWorks from 3:00–4:00 p.m. for a free workshop on mindful living and stress reduction. Kids and pets welcome!” Sounded reasonable. There was a bluegrass band at one brewery, “crafts for charity” at another, and a scandalously cheap happy hour at the new distillery. Kids and pets were welcome. A rap-metal band last heard from in 1998 was playing the Wilma. And yes, on Friday, “Drawings from Life” by Marcus Cull was being displayed in the basement of the Compound Eye as part of First Friday, 5:00–7:00 p.m. She considered using her copyediting powers for evil—dogs and firstborns executed on sight?—but Lyle had a tendency to check her work, especially when she’d been drinking. She changed her ex’s name to “Markass Krill,” hoping this might be subtle enough to slip through the censor’s net.

She got a text from Cal—“Gonna read chapter 8 good choice yes/no?” Was chapter eight the mine cave-in? The dissolution of the affair between the former slave and the alcoholic homesteader? Cal’s books tended to be quite—one might even say gratuitously—violent, and she hoped he wouldn’t read one of the many sequences of mangling or disfigurement. He’d gotten the idea, from movies and Cormac McCarthy, presumably, that the best way to depict “the past” was through unrepentant brutality, because that’s how it was. Maybe, she thought, better not to depict it at all, then. She responded to his text with an equivocal “yeh?”

It was hard, sometimes, putting up with the town’s cheerful, half-assed shtick, but most days the alternatives seemed worse. New York was a nightmare of pointless ambition, people waiting in endless lines for nothing. In Boston they didn’t bother with lines—they just jammed as many white people as possible into anyplace showing the Pats. She’d spent her early years in Princeton, with its liberal old-money complacency, dominated by “good families” who produced “good kids,” most of them zapped awful by divorce and private school. They’d never get her back there alive, at least not for more than a long weekend. She’d spent her childhood wanting to be from somewhere else, anywhere that didn’t draw a wince. Of course, name recognition was the whole appeal for her mother—when people asked where she lived, she could just say, “Princeton,” and they’d know she was a person of wealth and taste, whereas when people asked Leslie, she said, “Jersey,” then, if pressed, “Hopewell Valley, in Mercer County? Near Princeton?” Which was true—one good thing about New Jersey was that there were so many townships and villages and what have you that you could always just claim the nearest one that appealed. In Montana, the categories were broader. You were from Back East, Around Here, or California. It was best to not be from California.

She moved on to copyediting the arts section, her favorite part of the job. She hoped that if she hung around the office making snappy comments for long enough, she might someday be allowed to write a film or concert review. The current movie critic, Amy Freitch, trashed almost everything she saw in a biting, faux-naïve voice, saving her praise, it seemed, only for films about martial arts and animals. Leslie had gone camping with her once, and they’d taken mushrooms and read tarot cards. Amy claimed to know how to do it, but seemed to be making things up as she went along, possibly because she was hallucinating too much to interpret what the cards portended, probably just because she thought it was funny. Nevertheless, she’d predicted a hard year for Leslie, which had proved accurate. But wasn’t every year a hard year? Even a good year took a lot out of you.

Amy was sexy in a way that Leslie envied—boyish in her carelessness about clothes and posture but still long-haired and vulnerable. She also drank too much, like most of the people Leslie admired. She hoped that Amy would get a job writing for a real newspaper so that Leslie could take her place at the Door. She wouldn’t be as good as Amy right away, but she’d find her voice. “A voice like a girl with ants in her laptop,” they’d say, “marching in dissolved and scattered ranks toward some obscure but essential truth.” Most people she talked to disliked Amy’s pieces, so maybe she’d get fired. Leslie couldn’t in good conscience hope for that, but, well, it was out of her hands, wasn’t it?

Amy’s piece was pretty clean, but the week’s book review, of an eco-memoir about the grasslands of Eastern Montana, was a mess. It was by a recent graduate of the MFA program, an eco-poet who couldn’t, or chose not to, organize his sentences in the traditional manner. Nature careth not about such frivolities, but even an alternative weekly required the occasional comma. She spent a solid hour rewriting the piece, knowing she’d catch shit for being overzealous. But she didn’t want to contribute to the prevailing idea that everyone born after 1984 operated in a vacuum of good intentions without recourse to actual knowledge.

Despite her rejection of its trappings, Leslie had been thoroughly and expensively educated, and some of the content had stuck, even as she’d worked hard to smother her recollection of it under a scratchy blanket of booze and “other.” Oh, she was an expert on “encountering the other,” and she wasn’t talking about UM’s shit show of a diversity fair. She missed cocaine, but there wasn’t much of it in town, and the couple of times she had run across it, it was awful. The grungy kids did heroin—it was back! again!—but she’d always been afraid of that. She wanted to kill time but not, you know, kill it. Like, permanently.

* * *

She arrived at the bookstore a half hour before Cal’s reading so she could look at books and help set up. There was a local itinerant man sprawled on the sidewalk next to the door. He was moaning and slowly kicking his legs like he was swimming.

“Are you all right?” Leslie said loudly.

The man moaned louder and kicked with more purpose, in her direction. She went into the bookstore. Kim was behind the desk staring intently at the store’s computer screen.

“Have you seen that guy out front?” Leslie said.

“I don’t want to call the cops on him,” Kim said, eyes still on the screen. “But if Max gets here and he’s still out there, he’s not going to be happy. Mostly I don’t want to deal with it.”

“He doesn’t seem to be in a position to be reasoned with.”

“Accurate.”

Leslie wandered among the new-books tables, browsing through the poetry and the stuff from the independent presses. How the store stayed in business selling such strange and unpopular books remained its enduring mystery. There must have been enough people buying them to sustain the small shop, but Leslie never seemed to meet them. Secret intellectuals, speak up! Reveal yourselves!

The big problem that Leslie had, as far as she could tell, was that she was still, at twenty-seven, a person without well-established and verifiable thoughts or opinions about things. Other people were moving through the world and analyzing what they saw with some kind of consistency, a set of values that was sustainable and based on … something. What they grew up with, what they had developed later in opposition to what their parents had told them. Of course, she knew that there was no such thing as a balanced consciousness, or, if there was, it existed primarily in idiots and self-satisfied creeps, men mostly, who chose not to question their lives for fear of realizing they were terrible failures. But still. Everyone else always seemed to be doing better at it than she was.

“You want to help me with the chairs and stuff?” Kim said, finally turning to her.

“Sure.”

Kim was one of the good ones, a seriously noncomplacent person. She struggled openly with the borders of her life. She was writing a memoir about her peripatetic childhood, much of which involved traveling the country in a van with her family, moving between cultish New Age communities in dire poverty. Kim’s rejection of her family was partial and unhappy. She loved them and forgave them in principle but also had to stay away from them and have almost no contact with them whatsoever because most of their interactions triggered major depressive episodes.

Leslie had been at the Rose with Kim one night when Kim got a call from an unknown number. Usually she screened such calls, but she was drunk and expecting to hear from a man she’d recently slept with, so she answered it. Leslie watched as Kim listened in silence for a minute to someone speaking on the other end, and then held down the power button until the phone turned off.

“So that was my father?” she said. “I’m going to need you to hang with me for the rest of the night. Sorry.”

Then they’d gotten ugly drunk—drink-spilling, falling-off-of-barstools, shouting-at-the-TV drunk. Jamie had been there, blessedly, to drive them home, and they’d lain on the hardwood floor of Kim’s apartment, curled up against each other, Kim’s hair in Leslie’s face.

“I really hope I don’t puke in your hair,” Leslie said.

“If there’s any chance of that, you should not stay there,” Kim said.

“I’m sorry your family’s so fucked up,” Leslie said.

“It’s okay. I deserve it.”

“You were bad in a past life.”

“Past, present, future. There is no temporal zone in which I have not been, or will not be, a terrible person.”

“What did you ever do to anybody?”

“Nothing,” Kim said. “Not appreciated the gifts God gave me.”

“Well, what are you supposed to do?”

“Help people. Do something besides be selfish and wasteful.”

“You will,” Leslie said. “We’re still just little babies.”

“Drunk-ass babies,” Kim said. “Look out, America: the babies found the liquor cabinet.”

“This week’s episode: Babies get their stomachs pumped. Bad, bad babies.”

And more like that. They’d both thrown up eventually, Leslie in the middle of the night, Kim in the morning, though they’d made it to a trash can and the toilet, respectively. Respectably.

“Do you know this other girl who’s reading tonight?” Kim said.

“I didn’t know there was anybody else,” Leslie said.

“Megan D’Onofrio?” Kim said. “Lyric essayist?”

“Weren’t essays bad enough before they got lyrical?”

“Maybe she’s cool. Let’s try really, really hard to be open-minded. That might be interesting.”

“Do you have weed?” Leslie said.

“Yes!”

“My mind is open to smoking your weed.”

They went out to the alley behind the store, Kim carrying a box full of unsold literary magazines with the front covers ripped off for recycling. Leslie stood in the spot closer to the street as a lookout while Kim leaned against the wall and loaded the one-hitter painted to look like a cigarette. Their furtiveness was mostly for fun—they were aware of exactly no one who’d had any trouble getting stoned in Missoula. Still, Leslie found it hard to strike the surreptitious East Coast habits she’d developed as a teen during the late, feeble years of the war on drugs, even as, she’d been told, you could now smoke a joint on the street in Manhattan without fear of anything more than a ticket, at least if you were white.

“Yo, hit this,” Kim said, and Leslie did.

“We sold, like, three books today,” Kim said. “And they were, like, the gluten-free cookbook. All of them.”

Leslie passed the piece back.

“Is Max, what, selling organs on the side?” Leslie said.

“I wish he’d cut me in if he was,” said Kim, exhaling smoke. “I think he might just be rich somehow.”

Leslie took another hit.

“How’s the book coming?” she said.

“What are you, my agent?” Kim said.

“Sorry for being curious about your stupid life ambitions,” Leslie said.

“It’s going slow, man.” She looked down the barrel of the one-hitter and then tapped the ash out against the wall. “You think, like, Oh, it’s my life, I can write that, I went to graduate school. But you have to not hate what you write, you know? Which is hard if you hate yourself to begin with.”

“Maybe you should try not writing about yourself,” Leslie said.

“Who’d want to read that?” Kim said.

They went back into the bookstore, which was dim following the late-afternoon glare. Leslie was surprised by the sharp vertigo of despair—stoned in the company of her favorite friend, surrounded by good books. She had to admit that she was dreading Cal’s arrival and subsequent reading. She knew this was unkind, but lying to herself wasn’t going very well. Her attempt at self-deception involved rehearsing dramatic internal monologues of uncertainty. Well, I don’t know I’m unhappy. Thinking that Cal depresses me doesn’t mean he actually depresses me. But she knew, underneath these contortions, that if one had these thoughts for long enough, self-obfuscated or otherwise, one would eventually need to act on them.

“You okay?” Kim said.

Leslie looked up and realized she’d been standing at the poetry table unconsciously holding a waifish new Anne Carson hardcover.

“Can I use the computer for a minute?” she said.

“Let me just close out for the day,” Kim said. “Unless you’re buying that.”

“Right, like I’m going to just buy a book,” Leslie said. “Oh, look at me, I’m contributing to the local economy by purchasing important literature.”

“It does sound pretty dumb when you say it in that voice. Computer’s yours.”

Leslie fell into the padded swivel chair and opened her email. It seemed important to write this on a computer instead of her phone. In two blurry minutes—the pot helped, if that was really the right verb—she typed out a truncated version of the gracious, medium-true email to Marcus she’d been drafting in her head for days. She hoped all was well, was glad he was coming to town, hoped they could interact without issue. She signed it “With love, Les,” deleted that, retyped it, deleted it again, retyped it again, and hit send. Then she hurriedly logged out of her email, closed the Internet browser, and shut down the computer.

“Whoosh!” she yelled, and held her arms outstretched.

“Um,” Kim said. “Does that mean you’re ready to help me move the tables?”

* * *

They were unfolding the last of the chairs when Cal arrived with the beer, thirty-six jumbo cans from the brewery down the street, purchased at a bulk discount because they’d been badly dented during the production process.

“That guy out front’s in rough shape,” Cal said. “I tried to talk to him but he wasn’t having it.”

“You could call the police,” Kim said.

“That’s fucked up,” Cal said.

“Right, well, that’s as far as we got, too.”

“Nervous?” Leslie said.

“What, me worry?” Cal said. “I have faith in my material.”

Kim rolled her eyes behind his back.

Over the next fifteen minutes, the usual suspects wandered into the store, stepping around the drunken man. Max, the owner, was one of the last to arrive.

“How long has that guy been out there?” he said to Kim.

“Oh, him?” Kim said. “I guess he just showed up.”

“Come on, Kimberly,” Max said. He sat down behind the desk and put his head in his hands.

“Leslie, come help me,” Kim said. She hooked Leslie’s arm through hers and went outside. The man was sprawled to the left of the door, his head resting on his outstretched arm, which extended into the entranceway.

“Sir,” Kim yelled. “I’m really sorry but you need to move now, okay?”

He grunted and shifted slightly, revealing a puddle of urine.

“Sir, we don’t want to call the police, but you have to move now.”

“No cops,” he muttered. He opened his eyes and fixed them unfocusedly on Leslie. She told herself that she understood this, sympathized with it. She knew what it was like to have done too much, to be out of control. She also knew, or suspected, at least, that this really wasn’t like that, and that whatever sympathy she had for him was just pity, which she was trying to keep ahead of disgust in her emotional calculus.

“No cops,” the man said again, and began dragging himself down the sidewalk, leaving a trail of piss and garbage in his wake. They watched as he re-settled a few storefronts down, curling himself up in the doorway of the closed secondhand clothing store.

“Maybe we should call the cops?” Leslie said. “I mean, fuck, jail is better than that.”

“No, it’s not,” Kim said.

They went back into the store, where a few people had begun drifting in and picking up cans of Cal’s deformed beer.

“Hey, Les, this is Megan,” Cal said. “She’s my opening act. Or rather, I’m the, uh, cool-down mix to her energizing jams.”

Megan acknowledged this with a stifled laugh and shook Leslie’s hand. Megan was unusually tall and long-limbed and delicate. Leslie thought Megan was raising her eyebrows ironically but it turned out that was just how they were all the time.

“I’m looking forward to hearing your stuff,” Leslie said.

Megan shrugged.

“I think it’s good, at least,” she said.

“That’s a start,” said Leslie. “What are you reading?”

“It’s kind of a reflection on … I don’t know.” She let out a heavy sigh. “The body? I don’t really know what I’m doing anymore. It’s just … it’s really hard, you know?” She stared down at the floor.

“I’m sure you’re going to be great,” Leslie said. “This is a very forgiving audience.”

“Oh God,” she said, “I hope I don’t have to be forgiven for anything.”

* * *

Once the reading was under way, Leslie found it impossible to stay focused on what Megan was saying. The essay was as amorphous as advertised. It seemed to be about her body, and … icebergs? And her father, who was … also an iceberg? Leslie checked her phone and was disconcerted to see that she already had a response from Marcus. She had imagined—hoped was too strong a word—that he wouldn’t reply at all, that her email would simply be registered in her karmic ledger without any need for it to be acknowledged in actual reality. But here was Marcus, alive in her in-box. She looked up and saw that she was attracting a glare from her seatmate, an older woman with a long braid of white hair whom she’d seen at past readings. The woman pointed at Leslie, then at the reader at the lectern. Leslie pointed at her phone.

“I’m texting!” she said in a stage whisper. “Sorry, I’m too busy texting!”

This drew smirks from her friends sitting in the row in front of them, but she did put her phone in her bag. She wasn’t as rude as she pretended to be.

“If the heart is located outside the body, is it still of the body?” Megan read. “If ice is no longer solid, will it cease to be my heart? When I melt, who will drink what is left behind? Thank you.”

Amid the applause, Leslie returned to her phone. Marcus’s email was short. “Les,” it said. “Very glad you sent this. I think of you often. Can’t wait to catch up. Till soon, M.”

She was torn between hating her past self—the very recently past self who had sent that email—and enjoying the surge of gratitude she felt for Marcus’s response. She was skeptical of gratitude. Like humility, it was what people told you to feel after you’d been fucked over. Marcus had been awful, drugged-out and petty and selfish in the most unjustifiable ways. But the sheer reminder of his existence broadened her outlook. The world was not Missoula.

She felt something cold against the back of her neck and turned around.

“Cold Smoke?” Cal said, holding a beer. “There’s a couple IPAs left, too.”

“This is great,” she said. “Thanks.”

“Thought she was pretty good,” Cal said. “Really poetic language.”

“Definitely,” Leslie said. She sipped her beer, which was not as cold as it had felt against her neck.

“Hey!” Cal said to a retired UM professor. “So glad you could make it, Jim.”

“I’m still alive, aren’t I?” Jim said. He cuffed Leslie on the shoulder, harder than was necessary. “Got a cigarette for an old man?”

“I don’t think you’re supposed to have any, Jim,” she said.

“I’m eighty-two goddamn years old,” he said. “Nobody gives a fuck what I do.”

They’d been through this routine a few times. She guessed that Jim didn’t know her name, but he consistently recognized her as a reliable touch for nicotine. She was only a social and emergency smoker, but she socialized and encountered emergencies with such frequency, and cigarettes in this state were so cheap, that it made sense to keep a pack on hand, if only to distinguish herself from the parasites who bummed shamelessly the minute they’d had a sip of beer. Jim was exempted from this opprobrium, of course.

“I’ll come out with you,” she said.

On the sidewalk, he waved her away as she tried to light his cigarette, and lit hers first with a trembling hand.

“I said I wouldn’t go to any more readings,” he said. “But, what the hell, it’s something to do.”

“Do you like Cal’s writing?” she said.

“He’s a good kid,” he said. “Doesn’t mess around too much.”

This was interesting as a praiseworthy characteristic—all that most of the people Leslie knew did was mess around too much. She had, not quite consciously, enshrined it as something to be sought out in people, though she knew it was juvenile. Living here had brought out the hedonist in her. She’d never not had a tendency to drink too much, at least since she turned sixteen, but it wasn’t until she got to Montana that she really began to appreciate inebriation in its various forms as an art rather than an obligation. Cal, like a decent person, considered it neither.

“Yeah, I like him,” Leslie said.

“Not much of a writer,” Jim said. “Nobody’s perfect.”

Leslie offered him a big smile in thanks for this assessment, cruel as it was. Older men loved it when she smiled at them. Jim’s face, however, remained set in a scowl.

“Not that I know what the hell I’m talking about,” he said hurriedly. “You write? You want to write?”

“Wish that I did, I guess,” she said. “I’m one of those people with lots of ideas, you know?”

“Just fucking write something,” he said. “Worst-case it’s a piece of shit and you never show it to anybody. That’s what I told my students, at least.”

“Did they find that comforting?”

“A few of them wrote books. Probably no thanks to me. Nobody really cares if you write anything. I’ll be dead, at least. I don’t even know you.”

Leslie craned her neck around Jim to see if the homeless man was still on the sidewalk. She didn’t see him. Maybe he’d made it to the parking lot of Flipper’s, the bar-casino at the end of the block, which would have a legal obligation to call the police. Maybe, somehow, he’d found the energy to carry himself with something like dignity to a place that would take him in. It was hard to be entirely hopeless.

“It’s always good getting your perspective, Jim,” she said.

“No, it’s not,” he said. He tossed his lit cigarette into the street underhanded and shuffled back into the store. Leslie saw through the front window that people were sitting back down for Cal’s reading. She could slip away to a bar now and be truly blitzed by the time anyone could do anything about it. Kim would come find her eventually. She’d understand, even if Leslie was unable to explain herself. The goal was to be unable to explain herself. Goddamn Marcus. As if he were the problem. She went back into the store. She still had three-quarters of a beer to finish.

Marcus—no, Cal, Cal—knocked the pages of his story against the lectern like a professor on TV. He was wearing the “vintage” corduroy jacket with elbow patches that Leslie had tried to convince him to throw away due to its penchant for attracting mold. Cal blamed the closet it was stored in but kept storing it there, and kept wearing it to all events that could loosely be deemed “intellectual” in nature. And, well, maybe the authentic disgustingness of the thing made it a more authentic article of clothing for him, and maybe that was what gave him the confidence he needed to read his work in front of people.

Chapter eight, the section Cal had threatened to read, turned out to be a long scene of dialogue about the nature of political corruption between the Copper King William A. Clark and his nephew Terry over cigars and brandy. “I never bought anyone who wasn’t for sale,” was Clark’s well-worn contribution to posterity, and sure enough, Cal had him saying it within his first five lines of dialogue. It drew knowing snorts of recognition from the audience. The rest was exposition-heavy tragical-historical melodrama—“But Uncle, less than a decade ago, you promised Mother you would liquidate one-tenth of the holdings you accrued during your time i

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...