- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

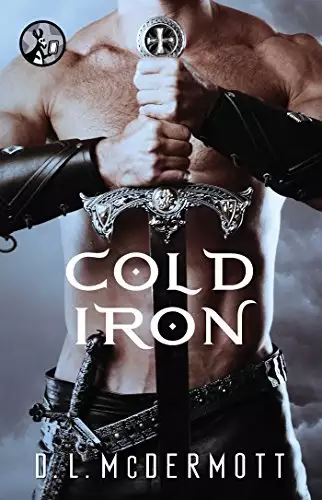

For fans of Jeaniene Frost and Kresley Cole, this full-length novel is the first in D.L. McDermott’s fast-paced, sexy paranormal romance series—available exclusively in ebook! The Fae, the Good Neighbors, the Fair Folk, the Aes Sídhe, creatures of preternatural beauty and seduction. Archaeologist Beth Carter doesn’t believe in them. She’s always credited her extraordinary ability to identify ancient Celtic sites to hard work and intuition—until she discovers a tomb filled with ancient treasure but missing a body. Her ex-husband, the scholar who stifled her career to advance his own, is unconcerned. Corpses don’t fetch much on the antiquities market. Gold does. Beth knows from past experience that if she isn’t vigilant, Frank will make off with the hoard. So when a man—tall, broad shouldered, and impossibly handsome—turns up in her bedroom claiming to be the tomb’s inhabitant, one of mythic god-kings of old Ireland, Beth believes it is a ploy cooked up by her ex-husband to scare her away from the excavation. But Conn is all too real. Ancient, alien, irresistible, the Fae are the stuff of dreams and nightmares, their attentions so addictive their abandoned human lovers wither and die. And this one has fixed his supernatural desire on Beth.

Release date: February 10, 2014

Publisher: Pocket Star

Print pages: 381

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cold Iron

D.L. McDermott

Chapter 1

If this is a tomb, then where’s the body?” Beth swept her flashlight over the empty bier against the wall. The couch was big, bronze, and impossibly well preserved. The Celt buried here must have been at least six foot. She could imagine his strong limbs and broad shoulders resting atop the soft furs. She stifled an impulse to stroke the downy pelts. Everything inside the mound was too fresh, too pristine, too perfect, from the spirals and whorls carved on the passage walls to the brightly woven tapestries decorating the central chamber, which should have crumbled to dust at the first whispered breath of outside air.

“Grave robbers,” Frank said with a dismissive shrug. It was an economical gesture, the slightest twitch of shoulders neither broad nor muscular. Funny how she hadn’t minded his narrow shoulders—or his narrow mind—when they were married. All she had seen was his boyish charm and dark good looks.

Frank had no imagination. But when Beth stepped inside an ancient tomb, she could close her eyes and see the past, conjure whole lives out of shards of pottery and heaps of ash.

The first time it had happened, she’d been seven years old, playing in her mother’s jewelry box. The iron brooch had drawn her like a magnet. It was surprisingly delicate for such heavy material, a circle of black metal chased with swirling knots, fastened with a pin through the center. In the past her mother had warned her not to touch it, but this time her mother wasn’t there and Beth couldn’t resist.

When her fingers closed around the cold metal, a shock traveled up her arm and visions filled her head: a woman, a stone circle, the forest floor. The images rushed past her, and it was only later, after years of work, that she learned to control them, to search them like the pages in a book, to speed them up and slow them down like a film.

Not that she had to work hard at the moment. This find was unprecedented. More lavish than any Celtic burial she’d ever seen—if it really was a burial.

The grave goods were all here: the bier and the wagon, the drinking horn and cauldrons. They were standing beneath a symmetrical, man-made hill, sixty meters across, inside a vaulted chamber eleven meters square. It all fit with what they knew of thousands of years of Celtic burial practices. It even smelled right. Like green grass above and new-tilled earth below. But it felt wrong.

She strobed the burial wagon with her flashlight. Gold. Lots of it. Bright yellow, high karat. A pair of daggers, several torcs, a set of shoe ornaments, and a two-handed sword with a hilt of hammered gold. Symbols of a potent, vibrant masculinity, extinguished two millennia ago. The weapons of a chieftain or a warrior king. They were dazzling, but they shouldn’t be here, not neatly laid out in the bed of the burial wagon, not if the tomb had been raided before. It didn’t add up. “Grave robbers don’t steal bodies and leave gold behind.”

“Then the body was eaten by scavengers. Wolves, maybe,” Frank offered. He fingered one of the glimmering neck rings lying on the wagon.

Nothing destroyed artifacts faster than handling. The first rule for touching ancient objects was don’t. Frank knew that, but Frank thought rules were for other people. When she’d been a young and impressionable graduate student, she’d thought that was cool. Part of Frank’s sophisticated appeal. She knew better now.

“Wait,” she said. “Use my gloves.” She tucked her flashlight under her arm and dug into her jacket pocket. No gloves. She shifted, tried her pants pocket, and dropped her flashlight.

It hit the floor and went out.

The darkness was absolute. Beth felt the massive weight of the hill above them, the deep chill of the stone walls. She’d never been skittish underground before, but she was unsettled now.

She needed the flashlight. It couldn’t have rolled far, but the darkness scrambled her bearings. She reached for the wall—and brushed Frank’s groin instead.

She jumped back, but he grabbed her wrist and tugged her hand over his crotch. “I should have remembered. Burial chambers make you hot. The bier looked sturdy enough if you feel like a trip down memory lane.”

That was a street she’d rather not revisit. She had worked too hard to learn to resist Frank’s allure. “No thanks.” She yanked her wrist back. “This is all wrong. It’s a Stone Age monument filled with Bronze Age treasure, as though this tomb remained in use for thousands of years. And no one is buried here. This place was sealed tight as a drum. It hasn’t been robbed or scavenged, but it’s got everything a burial needs, except a body. Doesn’t that bother you?”

She could hear him moving about the chamber. “Nope. Collectors don’t buy mummies, Beth. They buy objets d’art. Corpses don’t fund university chairs, and they don’t underwrite expeditions. They don’t get you invited to lunch with the minister of culture. Gold does.”

She couldn’t see him, but he must have moved closer again, because she felt a breath tickle her neck. It was disturbingly arousing, which was bizarre, because while she’d always felt attracted to Frank, drawn by his almost hypnotizing charm, she’d never found Frank’s attentions arousing. She only understood that in hindsight, of course. What she had felt, during their courtship, was flattered. She’d basked in the attention of her idol and thought she was special.

A hand ghosted over her breast and her nipple hardened. She bit back a moan. “Stop that.”

“Stop what?”

The hand was gone.

Click. Light bloomed in the darkness. Frank had the flashlight. On the other side of the tomb.

The hair on the back of her neck rose. “I need to go outside.”

Frank looked at her, puzzled. “What’s with you?”

“Nothing. I just need air.” She tried to get herself under control. There was nothing to fear underground. She’d climbed down into a dozen burial mounds in her career. Archaeology wasn’t for the easily spooked, or the claustrophobic. She tried to tell herself that the breath on her neck, the hand at her breast, had been air currents. Or Frank messing with her. But the air in the room was completely still, and she’d never seen Frank move that fast for anything.

Frank smirked. “The locals have you rattled, don’t they? With all that talk about fairy mounds and the bowls of milk and honey they leave outside their doors. You spend so much time writing down their superstitions, you’ve started to believe them.”

“Their folk ways,” she said, finding comfort in the familiar, arguing with Frank, “are what helped me identify this tomb.”

“Satellite photography identified this tomb,” he replied. “And all the others we’ve found.”

But they both knew that wasn’t true. Beth didn’t need aerial photographs to find Celtic sites. Maps would do, even crudely drawn ones. All she needed was an idea where to look. Folklore always pointed the way. When a village said the nearby hill was a fairy mound or the clearing in the woods was a Druid circle, Beth could touch the spot on the map and know. A shudder would pass through her and something low in her belly would clench.

It was why Frank—handsome, sought-after Frank—had courted and married her.

“None of this gold,” she said, putting the past from her mind, “will end up on the antiquities market, or in the university museum. We signed strict agreements with the Irish government before we started digging.”

Frank shrugged once again. She didn’t like that shrug. He was caught last year in Mexico City trying to board a plane with his pockets stuffed full of Mayan seals. Naturally the university had pulled strings to smooth the whole thing over. They couldn’t have their golden boy spending the night in a Mexican jail.

She would have to watch him. Catalog the mound as quickly and thoroughly as possible before anything went missing. She had a feeling that if they took anything that didn’t belong to them from this tomb, they’d face someone—or something—much more dangerous than the police.

The digging woke him. He sent his mind out through the roots and the soil, to the west slope of the hill, where sometimes a sheep wandered and a shepherd followed, though not for many years now.

The locals knew better than to disturb his sleep. They preferred the Good Neighbors quiet beneath their hills. The Fair Folk, the Beautiful People, the Lords and Ladies; the Irish had many names for his kind because they were afraid to call the Aes Sídhe what they were: bored, cruel, wicked, and soulless. Conn knew he was all three, his humanity worn away long ago, because immortality bred contempt for life. But he judged he’d slept long enough to rekindle his appetites, to dull some of the viciousness—the fatal flaw of the undying—he’d sensed in himself when he’d last walked in the world.

He knew it when he felt the girl.

She wasn’t a child of the local earth. He could sense that. But she had the old blood, dancing hot beneath moon-pale skin. His cock stirred. Appetite. Desire. He would have her. The villagers would offer her up with the milk and the honey, glad he wasn’t asking for one of their own. They had to. There was no one to gainsay him. Their new priests had no power over the earth or the trees, no power over the Fae.

He liked her hair. Chestnut. Her curves, soft like the hills. And her eyes, bright, brown, cow-like. He had not encountered a woman so appealing to him in decades. Her beauty was not the passing flower of youth, but the enduring elegance of classical proportions. Full breasts, a defined waist, and lush hips. She climbed the hill with a hunter’s stealthy, athletic grace, and he imagined how sinuously she would move beneath him in his bed.

She had a man with her, another foreigner—slender, almost pretty, but not of the blood, and weak. Brother, father, husband, he couldn’t tell. The man’s aura was clouded like bog water. Unlikely to fight for her, but easy to kill if he did. The sort who failed to defend his woman’s honor, then asked for compensation when she was ravished.

He smiled at the thought. Firm, warm, living flesh beneath him, engulfing him. Digging through the sweet green grass to reach him. Her eagerness was touchingly human. He would enjoy spreading her, drinking in her pleasure and her release. If she pleased him as much as he hoped, he would keep her for a time. And then he would leave her, unable to taste mortal food or enjoy a mortal man’s bed, because he could not change his nature. Ancient, cold, tethered to the world only through the vicarious pleasure and pain—the one had no savor without the other—of humans.

Yes, he would have her, but he must satisfy more basic appetites first. He took his spear and his knife and passed through the hill—earth, wood, water, grass—changing from one thing to another, channeling his essence through each living particle, because all living things were one with his kind, to emerge in the wood at the other side of the village, and hunt.

Beth couldn’t shake her unease or, if she was honest with herself, her unwanted arousal. She tried to tell herself that her concerns were real and mundane: Frank and the gold. She’d hired a watchman to camp at the site overnight and planned to return first thing in the morning to catalog the contents of the tomb before her ex had a chance to palm anything, but that wasn’t why she was still sitting in the curtained window seat in the taproom of the inn where they were staying, nursing her half pint of bitter. Worrying about Frank’s sticky hands shouldn’t make her nipples hard and the place between her legs throb.

The pub attracted a rough crowd at night. She normally didn’t stay this late, but after the incident in the tomb, the thought of returning to her room alone was unappealing. She wanted lights and people.

But not company. She’d already fended off the advances of an unsavory local, a granite-dusted young quarryman who hadn’t taken her rejection kindly. Now he was nursing his drink and his resentment at the bar.

Of course Frank and his current “research assistant” were there, too.

When Beth and Frank were married, he was more discreet with his graduate-student hookups. He never picked the youngest or the prettiest ones, and at least maintained the pretense of evaluating their credentials. But no longer. Christie Kelley wasn’t bright. She didn’t have brains, or brawn, which would at least have been useful on a dig. She was whip thin and, Beth suspected, starved herself to stay that way. Fragile. A decided antidote to Beth’s feminine curves.

Beth had been naive enough, the first time one of her “hunches” paid off, to allow Frank to take the credit. It had been a remarkable find, a hill fort that had at one time contained at least thirty houses. Wind and weather had so changed the topography that the outline was no longer visible, even in aerial photography, but Beth had felt it there when her fingers brushed the site on the map. She had known.

Frank had convinced her that the university would never fund them if she led the dig, never publish their findings if she authored their paper. She was only a graduate student, after all, and didn’t have Frank’s Ivy League pedigree; plus he was already a full professor and a name in the field.

Her hill fort had made his career.

She’d been living with him when they’d started their second expedition and too besotted with her idol to argue for credit. He knew so much about their field, had met so many of the heroes in her professional pantheon, traveled to so many of the places she longed to go. Just being with him, she could feel a little of his personal glamour wear off on her.

By the time of their third major discovery they were married, and from the outside their partnership appeared perfect. They were a globe-trotting academic couple, invited to lecture at cultural institutions around the world. When Beth’s name appeared as coauthor of their treatise on the new findings at Hallstatt, everyone assumed that her role was that of devoted academic spouse: editor, cataloger, subordinate. When she insisted on an equal share of the credit, he began sleeping with his students again, and she refused to identify any more sites for him. Then he betrayed her in an act that still turned her stomach whenever she thought about it. After the divorce, she found herself shut out of grants to dig unless she partnered with her ex-husband.

Beth almost felt sorry for Christie Kelley, nestled in a corner table at the other side of the taproom with Frank, sipping her half pint and staring up at him with starry-eyed adoration. She could remember feeling like that about him.

Beth had never met anyone before him who’d shared her fascination with the ancient Celts. She had not connected them with the iron brooch in her mother’s jewel box until she was fourteen, on a class trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, when the guide had led them past a gallery that Beth had known she had to enter. The compulsion was so strong that she’d been parted from the group and was standing alone in a vast hall in front of a massive glass case before she’d even realized what had happened. Her teachers and classmates, oblivious to her defection, had continued on to the Greek and Roman galleries.

In the hush of that empty chamber Beth had felt it, the same thrill her mother’s brooch had given her, magnified a hundredfold. Though the brooch had been snatched away and hidden, Beth had always continued to be aware of its location. There were similar brooches in the case. Several in iron, two in silver, one in gold. Pennanular, she later learned. Moon shaped. She’d pressed her fingers to the glass, longed to touch them, then gone home, searched out her mother’s brooch, and started to learn to harness her strange ability. That summer she’d begun volunteering every weekend at the museum, desperate for a chance to touch the objects in that gallery.

Christie Kelley wasn’t enamored of Frank for his knowledge of Celtic archaeology, though. That wasn’t even her specialization. Her thesis was focused on the early Maya. No, she was attracted by Frank’s charm, his fame, his power in the department. His patronage could make or break her career. No wonder she stared up at him with such slavish adoration.

But Frank wasn’t looking at Christie now. He was looking straight across the room at Beth, smiling. He winked, then produced one of the glittering torques from the tomb out of his pocket. He slid it around Christie Kelley’s twig-like neck, then basked in her fawning praise. Beth had fallen for the same tricks when she was his student. Frank playing the great archaeologist, Schliemann, decking his wife in the jewels of Troy.

Only, this wasn’t the nineteenth century, and archaeologists didn’t loot graves. They cataloged them, preserved them, wrote about them for the public. The torc belonged in the tomb. She contemplated getting up and retrieving it. With a sinking feeling, she realized she couldn’t. Not here, in public. She would look like a shrew. The jealous ex-wife snatching jewelry away from the pretty young girlfriend. Ugh.

The hairs on the back of her neck rose. There was something behind her. Something outside the window. She tried to tell herself that the inn was old and the windows drafty, but the danger was real, and she knew it in her bones. Whatever was out there, it had power over her. It intensified the low throb between her legs and made her breasts ache. She had to get out of the bar, away from the window.

She stood, jostling her table and sending beer slopping over the rim of her glass. The bartender darted a quick, worried glance her way. Of course he did. She was behaving like a drunk. But the couple at the next table was also staring at her as was the quarryman at the bar. Was her blouse unbuttoned? She looked down to check, felt even more foolish. Her nipples were pebbled, visible through the soft cotton of her blouse.

She looked back up. Now the quarryman and his buddies were smirking, but the bartender and the old-timers near the fire were studiously looking the other way. Was she imagining all this? She felt flushed, awkward, self-conscious. She couldn’t remember a moment like this since middle school—everyone aware of her and ignoring her at the same time. Except Frank and his floozy in the corner, too absorbed in themselves to notice.

She edged out of the window seat and ran smack into the quarryman. And his friends. Five of them. “Don’t leave yet. Stay and have a drink with us,” he drawled, backing her into the alcove. She could smell whiskey on his breath. She darted a quick look at Frank, still absorbed in Christie Kelley. No help there.

“No thanks. I was just leaving.” His friends were sliding onto the bench behind her, cutting off her retreat.

And the thing outside the window, the danger her body could feel like an icy wind, was growing closer. She had to get out of there.

There was no room to maneuver, but she knew from her earlier clumsiness that the table wasn’t screwed to the floor. She grabbed the apron of the heavy wooden top and shoved. The bastard menacing her swore and jumped back, and she scrambled past him.

She fled from the room, into the front hall, and straight into the neat, silver-haired landlady. “I’m so sorry,” Beth murmured, trying to steady the tottering innkeeper. Mrs. McClaren was one of her best sources of local folklore, had talked for hours about the fairy mound when Beth had first visited last spring. The woman was tiny and frail, eighty years old if she was a day, but her grip on Beth’s wrist now was like a vise.

“I’ve got to change your room, dear,” she said. It was an ordinary enough statement, but Mrs. McClaren sounded as spooked as Beth felt.

“Now isn’t a good time, Mrs. McClaren,” Beth said, trying to loosen the woman’s hold.

“I’ve got a nice room right across the hall with an iron latch on the door,” she persisted.

“An iron latch won’t keep him out.” Beth recognized the speaker. The old man sitting behind the desk was Mr. O’Donovan. The locals accounted him a great authority on the sídhe, the mythical, semidivine inhabitants of the fairy mounds, but when Beth had approached him on her first visit to Clonmel, the man had refused to speak to her. When she’d returned with Frank, the old man had marched up to them and told them to leave the mound alone. Then he’d marched off and never said another word. Until now.

“Who are you talking about, Mr. O’Donovan?” Beth asked.

His eyes were wild and his smile was gleeful. Beth didn’t like that at all. “You know who. You came here looking for them. You woke the worst of a bad lot. I warned you not to dig in the mound, but you wouldn’t listen, and now he’s come for you.”

“Bite your tongue, old man,” Mrs. McClaren said, and turned to Beth. “Pay no mind to him. Sit here for a minute and I’ll have your things moved across the hall into the nice room with the batten door. An iron latch and iron bands. Old as the inn. Strong in the earth,” she said, as though she was recommending chocolate biscuits or vanilla cake, something ordinary and pleasant.

“Won’t keep him out,” the old man cackled. “It would take iron windows and iron walls and an iron floor and a roof of iron to keep him out. And even then, he’d get to you. And it’s no more than you deserve. No decent woman goes searching for the likes of them.”

It was too much. Beth bolted. Up the stairs, into her room with the brass doorknob, and the brass bolt, and the brass window latch. She locked all three, then took a deep breath and rested her forehead against the cool glass of the window.

“Don’t let them frighten you.” The voice was musical. Wind in the forest. Deep and primal. Musky sweet like honey. It compelled her to turn and behold the speaker, who leaned casually against the door she had just locked.

The man was well over six foot, and his skin was the ivory of Viking raiders and Celtic heroes. His hair was pale gold and arrow straight, woven in slender braids. She recognized the silver dagger at his hip, twin to the blade in the tomb, tucked into a wide leather belt that cinched soft fawn trousers. His linen tunic was embroidered by the same hand as the tapestries in the burial chamber, and around his neck was a torc finer than the one Frank had palmed that afternoon.

Strong limbs and broad shoulders in soft pelts. It flashed through her mind, and though the rational academic in her said no, the woman in her said yes, this is him. The Celt from the tomb. Rational Beth said, It’s some local joker playing with you, but irrational Beth, the Beth who could feel the old places through maps and pictures, heard a voice whisper, The Good Neighbors. The Fair Folk. The Lords and Ladies who dwell in the earth. The Sídhe.

You’ve always known they would come for you.

Conn had chased the deer for miles, not because he had to, but because he enjoyed feeling the grass beneath his feet and the wind in his hair, and because prey deserved the dignity of the hunt. He roasted and ate his fill, washed in the stream that ran down toward the mill, and left the carcass hanging outside the mill door so that word might spread. “Bring your tithe to the mound,” they would say. “Keep your daughters inside. One of the Old Lords walks abroad, and requires meat for his table.”

The inn he remembered. He could feel the age of it in the timbers, could read its history through the wood. A stand of living trees four hundred years ago, hewn and new, rooted to this place. He had liked it then, with its thatched roof and shuttered windows, better than the stone buildings the invaders brought. He liked it less now. The building was the same, but it stank, inside and out, of black iron and burning smoke. The filthy tar of the long dead beasts under the earth was poisoning the living wood and clay, driving the clamorous engines that rumbled past at unnatural speed, drowning out the sounds of the birds in the trees and the wind in the meadow. The girl was here. And her weak man. And another foreigner, a different woman. Younger. Callow. She smelled of base metals and dead beasts, too, bright and clattering like the smoke engines.

He entered the low door of the inn, and the old man sitting by the fire nodded. “I warned her,” he said. “She wouldn’t listen to an old man. But here you are, come to claim her. And it’s no more than she deserves.”

“Quiet!” The old woman curtsied, the creak in her arthritic knees audible as the snap of the fire. She tried to keep her eyes downcast, but her gaze was drawn to him. He knew the glamour he cast, irresistible even to a woman long past youth, wondered what it would be like to be obliged to woo a woman, to win trust and affection, rather than receive them as his due.

He followed the trail of the woman, his woman, her scent now spiked with fear, into the common room. The crowd fell silent as he entered. all save the granite-dusted men clustered in the window seat, where she had been. He could feel her lingering warmth there, see the print of her lips on her unfinished glass of ale.

He strode to the table, lifted the beaker, and licked the taste of her mouth from the rim. Summer fruit and honey wine.

He addressed the biggest of the quarrymen. “Where is the woman who was sitting here?”

The big man stood. Almost as tall as a Fae. Conn caught another tendril of the woman’s scent, all panic and indignation, clinging to the man’s clothes.

“What’s it worth to you, pretty boy?” the man asked. His friends laughed. Memory, it seemed, was growing short in Clonmel. The quarryman reached for a lock of Conn’s hair, and faster than the human eye could see, Conn seized the man’s wrist and broke it. Beneath the skin, the two long bones jostled and splintered like dry kindling.

The man screamed. His nearest friend swung a fist at Conn. Foolish. But this one hadn’t touched the woman, so Conn decided not to maim him, and merely picked him up bodily and dropped him onto the table, shattering it.

The rest thought better of challenging him.

“Where is the woman?” This time he addressed the room at large.

“Upstairs,” said the bartender.

The callow girl who smelled of metal, and was, he noticed with amusement, wearing one of his lesser ornaments filched from the mound, tugged at the sleeve of the foreigner. “Frank,” she said. “What’s going on? Why doesn’t someone call the police?”

“She’s right,” Frank hedged, nodding at the bartender. “You should call the police.”

“For the love of God, shut up,” said the bartender.

But the woman persisted. “Aren’t you going to do something? He’s threatening your ex!”

This was entertaining. Conn watched as the foreigner—Frank—deliberated. The man wished to keep both women, not because he valued either one, but for status. The arrangement was an old one, a woman to make his home, and another to warm his bed. But this Frank was a fool. He had made a queen out of his concubine, and a drudge out of an empress. No good could come of it, and he deserved to lose both.

“I’ll go check on her,” Frank said to the woman. But Conn held up a hand, and two strong villagers—memories apparently in good working order—grasped the outlander’s shoulders and held him there.

Conn smiled. He enjoyed seeing the man humbled. It was one of the delights of waking. Food and drink and sex and the taste of mortal emotion. Salt and sweet. Anguish and joy.

He took the stairs two at time. The hall was long and dark, the only light coming from beneath the door at the end. Her room. He crossed the hall and passed through the door.

She stood at the window, her temple resting aga

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...