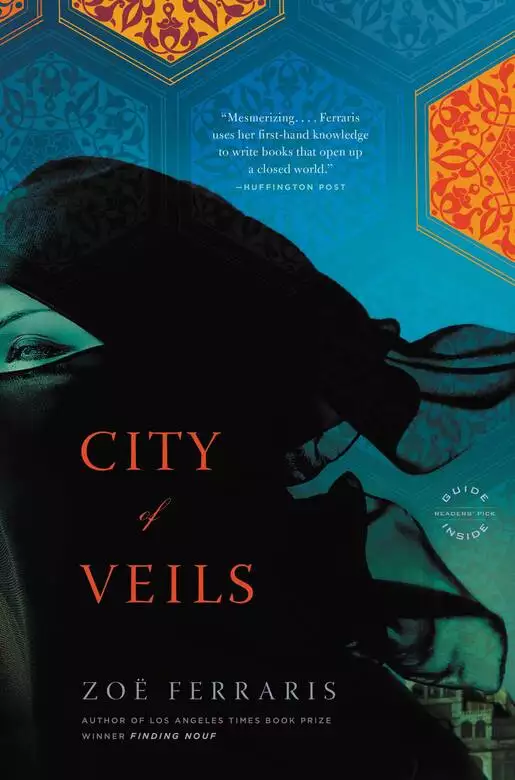

City of Veils

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

When the body of a brutally beaten woman is found on the beach in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Detective Osama Ibrahim dreads investigating another unsolvable murder-chillingly common in a city where the veils of conservative Islam keep women as anonymous in life as the victim is in death.

But Katya, one of the few females in the coroner's office, is determined to identify the woman and find her killer. Aided by her friend Nayir, she soon discovers that the victim was a young, controversial filmmaker named Leila. Was it Leila's connection to an incendiary Koranic scholar or a missing American man that got her killed?

City of Veils combines a suspenseful and tightly woven mystery with an intimate and nuanced portrait of women's lives in the Middle East.

Release date: July 24, 2010

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

City of Veils

Zoë Ferraris

to Saudi Arabia to live with her then husband and his extended family, a group of Saudi-Palestinian Bedouins, and she uses

her experience to bring alive the country’s culture and contradictions. But City of Veils does more than that, providing unique insights into the minds of men brought up to fear women and the desire they inspire.

Claustrophobic and totally original, this is modern crime fiction at its very best.”

—Joan Smith, Independent

“Fascinating and eye-opening…. A fast-paced mystery novel…. Ferraris’s characters are compelling and utterly human. She is

a formidably talented writer, whether she is describing the subtle nuances of Saudi romance, a terrifying desert sandstorm,

a visit to a Saudi lingerie shop, or a public execution. City of Veils should appeal not only to mystery aficionados but to anyone who enjoys reading intelligent novels.”

—Diane White, Boston Globe

“With a tight plot, nice action, good suspense, and a sweet touch of romance, City of Veils is an entertaining story…. Ferraris did an excellent job of combining elements of a great crime drama with a nice twist of

Arabic personality and culture.”

—Melissa Willis, TheChristianManifesto.com

“While Ferraris writes about the Saudi theocracy with the critical eye of a liberated Western woman, this doesn’t prevent

her portrait from being affectionate and subtle…. Ferraris creates a convincing portrait of Saudi Arabia.”

—David B. Green, Haaretz

“Mesmerizing…. Ferraris uses her firsthand knowledge of married life in a Saudi Arabian family and her capacious skills at

imaginative storytelling to write books that open up a closed world and allow a reader to enter at will…. Ferraris combines

the strange and familiar and comes up with something fabulous…. Wonderfully engaging…. Ferraris offers complex characters,

fully realized landscapes, and clever plots that twist and turn, eventually reaching resolutions that are ultimately sad but

absolutely satisfying.”

—Nina Sankovitch, Huffington Post

“A thrilling, well-written literary mystery.”

—David Gutowski, Largeheartedboy.com

“City of Veils presents a searing portrait of the religious and cultural veils that separate Muslim women from the modern world.”

—Publishers Weekly

“City of Veils offers a sensitive look at life in the city of Jeddah. The novel has a strong sense of place—the author knows the territory….

Ferraris has a good feel for her two main characters and a beautiful sense of poetic timing…. A reworking of a typical police

procedural scene is brilliant.”

—Owen Hill, Los Angeles Times

“A whopping good tale…. Every detail of this novel is exact and exciting…. A riveting literary mystery that will hook readers

with every sordid, fascinating, even heartwarming detail until the final page…. Timely, exciting, urgent…. Not to be missed.”

—Barbara Dickinson, Roanoke Times

“Nail-biting…. Smart and thoroughly entertaining…. An exemplary pick from the ‘crime fiction introduces new worlds’ front….

Tension is everywhere as Ferraris builds suspense from both domestic concerns and the grievous crime…. As her book makes clear,

it’s absolutely vital that Americans learn more about Saudi Arabia’s people and their thoughts about the outside world.”

—Sarah Weinman, Salon

“A unique mystery…. Ferraris clearly has fun dramatizing this complex society, which is morally conservative but technologically

advanced…. Her novel feels fresh, thanks to her ability to bring her idiosyncratic characters and the extreme setting to life,

in vivid and taut prose. Her description of Miriam being buried in her car in a sandstorm is so real and awful, you can practically

feel the grit filling your eyes and ears…. Armchair travelers eager to learn about a remote culture without leaving the comfort

(and safety!) of home are sure to find what they’re looking for.”

—Malena Watrous, San Francisco Chronicle

“It’s a double whammy: a riveting portrait of an extraordinary society and a satisfying police procedural to boot.”

—Carla McKay, Daily Mail

“Ferraris’s second novel more than lives up to the promise of her magnificent debut, Finding Nouf…. The plot is thrilling, with plenty of twists and turns, and all the characters well drawn, but what makes this novel really

extraordinary is Ferraris’s knowledgeable and sensitive depiction of a place where religion, used as a blunt instrument, has

given rise to a stultifying, paranoid, and sex-obsessed society, where women are forcibly infantilized and men are emotionally

bonsaied. Highly recommended.”

—Laura Wilson, Guardian

“A grippingly detailed and nuanced murder mystery…. Ferraris twines together the satisfactions of the police procedural, path-lab

expertise, and gumshoe flair. Other genre standbys—a riddle posed by a cache of ancient manuscripts; a climactic fight to survive, here against the suffocating horrors of a tremendously described

sandstorm—further tighten suspense. As the twisting plot reveals what lies behind the killing of an Arab woman and the disappearance

of an American security specialist, the novel grips you with its portrayal not just of outlandish death but of everyday life

in Saudi Arabia…. Acute and nuanced—especially in its sensitive and sympathetic treatment of decent Muslims harassed by fundamentalist

fatuities—this is a detective novel that doesn’t only offer a murder mystery but also engrossingly explores moral, social,

and psychological quandaries.”

—Peter Kemp, Sunday Times

“A gripping tale of passion and detection…. Ferraris’s confident debut, Finding Nouf, is followed by an even more impressive performance in City of Veils. Authenticity is assured…. She expertly weaves an excellent whodunit into an engrossing portrait of a vibrant society, full

of sexual, religious, political, and moral contradictions.”

—Marcel Berlins, Times

“In this exhilarating tale of duplicity and betrayal, Ferraris masterfully captures the nuances of the Saudi culture and its

women, while brilliantly exposing the conflict between tradition and desire.”

—Mahbod Seraji, author of The Rooftops of Tehran

“City of Veils is a sensitive portrayal of hidden emotions, and at the same time an intense and thoughtful thriller. Ferraris’s intimate

knowledge of the daily frustrations and humiliations of a woman’s life behind the veil is vividly conveyed. It is a disturbing

picture but one we need to see. I congratulate Ferraris.”

—Kate Furnivall, author of The Russian Concubine

“Zoë Ferraris lifts the veil in Saudi Arabia. A master storyteller, she weaves an engrossing, taut tale of conflicting cultures:

Bedouin, expat, and the Saudi royalty in a society ruled by the religious police, hidden passion, and greed. I couldn’t put

City of Veils down.”

—Cara Black, author of Murder in the Marais

“A marvelous book. In City of Veils, not only does Zoë Ferraris display a richly nuanced understanding of Saudi culture, but

she also demonstrates the instinctive authority of both an elegant stylist and a born storyteller.”

—David Corbett, author of Do They Know I’m Running?

“Zoë Ferraris delivers the Muslim Da Vinci Code. It kept me up at night. I loved it!”

—Ranya Idliby, coauthor of The Faith Club

“Superb. Like its predecessor, Finding Nouf, City of Veils proves that Zoë Ferraris is capable of writing novels that both entertain and educate. For every intriguing plot twist there’s

also a riveting cultural moment, a carefully choreographed literary dance that moves seamlessly toward a denouement that will

both satisfy and challenge the reader…. There’s no question that Zoë Ferraris is one of the most important new voices in crime

fiction.”

—Michael Koryta, author of The Ridge

“A gripping, many times disturbing, story of murder and the search for justice in an ancient society at odds with a woman’s

fight for independence.”

—Kathleen Kent, author of The Heretic’s Daughter

“Taut and intelligent, set against a troubling backdrop of brutality, oppression, and searing desert heat.”

—Anne Zouroudi, author of The Messenger of Athens

The woman’s body was lying on the beach. “Eve’s tomb,” he would later come to think of it, not the actual tomb in Jeddah that

was flattened in 1928, to squash out any cults attached to her name, nor the same one that was bulldozed again in 1975, to

confirm the point. This more fanciful tomb was a plain, narrow strip of beach north of Jeddah.

That afternoon, Abu-Yussuf carried his fishing gear down the gentle slope to the sand. He was a seasoned fisherman who preferred

the activity for its sport rather than its practical value, but a series of layoffs at the desalination plant had forced him

to take up fishing to feed his family. Sixty-two and blessed with his mother’s skin, he had withstood a lifetime of exposure

to the sun and looked as radiant as a man in his forties. He hit the edge of the shore, the hard-packed sand, with an expansive

feeling of pleasure; there were certainly worse ways to feed a family. He looked up the beach and there she was. The woman

he would later think of as Eve.

He set his tackle box on the sand and approached carefully in case she was sleeping, in case she sat up and wiped her eyes

and mistook him for a djinn. She was lying on her side, her dark hair splayed around her head like the tentacles of a dangerous

anemone. The seaweed on her cloak looked at first like some sort of horrible growth. One arm was tucked beneath the body;

the other one was bare, and it rested on the sand in a pleading way, as a sleeper might clutch a pillow during a bad dream.

The hand was mutilated; it looked to be burned. There were numerous cuts on the forearm. Her bottom half was naked, the black

cloak pushed up above her waist, the jeans she was wearing tangled around her feet like chains. His attention turned to the

half of her face that wasn’t buried in sand. Whole sections of her cheeks and lips were missing. What remained of the skin was swollen and red,

and there were horrible cuts across her forehead. One eye was open, vacant, dead.

“Bism’allah, ar-rahman, ar-rahim,” he began to whisper. The prayer spooled from his mouth as he stared dumbfounded and horrified. He knew he shouldn’t look,

he shouldn’t want that sort of image knocking around in his memory, but it took an effort to turn away. Her left leg was half buried in the

sand, but now that he was closer, he saw that the right one was cut around the thigh, the slashes bulbous and curved like

tamarinds. The rest of the skin was unnaturally pale and bloated. He knew better than to touch the body, but he had the impulse

to lay something over the exposed half of her, to give her a last bit of dignity.

He had to go back up to the street to get a good cellular signal. The police came, then a coroner and a forensics team. Abu-Yussuf

waited, still clutching his fishing rod, the tackle box planted firmly by his feet. The young officer who first arrived on

the scene treated him with affection and called him “uncle.” Would you like a drink, uncle? A chair? I can bring a chair.

They interviewed him politely. Yes, uncle, that’s important. Thank you. The whole time, he kept the woman in his line of sight.

Out of politeness, he didn’t stare.

While the forensics team worked, Abu-Yussuf began to feel crushingly tired. He sensed that shutting his eyes would lead to

a dangerous sleep, so he let his eyes drift out to sea, let his thoughts drift further. Eve. Her real tomb was in the city. It had always seemed strange that she was buried in Jeddah, and that Adam was buried in Mecca.

Had they had a falling-out after they were exiled from the Garden of Eden? Or had Adam, like so many men today, simply died

first, giving Eve time to wander? His grandmother, rest her soul, once told him that Eve had been 180 meters tall. His grandmother

had seen Eve’s grave as a girl, before the king’s viceroy had demolished the site. It had been longer than her father’s entire

camel caravan.

One of the forensics men bent over the body. Abu-Yussuf snapped out of his reverie and caught a last glimpse of the girl’s bare arm. Allah receive her. He leaned over and picked up his tackle box, felt a rush of nausea. Swallowing hard, he looked up to the street and began

to walk with an energy he didn’t really have. Uncle, can I assist? This was another officer, taller than the first, with a

face like a marble sculpture, all smooth angles and stone. The officer didn’t give him time to protest. He took Abu-Yussuf’s

arm and they walked up together, taking one slow step at a time. The going became easier when he imagined Eve, a gargantuan

woman stomping across cities as if they were doormats. She could have taken this beach with one leap. Pity it was only the

modern woman who had been rendered so small and frail.

24 hours earlier

In the loading garage of Al-Amir Imports, the great bustle of activity drowned out the sound of Nayir’s cell phone, which went

unnoticed in his pocket. There were tents to be folded, rations to be stored, and water to be measured, not to mention that

the GPS navigation network still hadn’t been brought online. While the younger Amir brothers were raising a fuss about the

static on the screens of their handhelds, an assistant came rushing up to warn Nayir that the servants had forgotten to stock

salt tablets.

Nayir went straight to the Land Rover in question—cell phone still happily jangling—and foraged in the trunk for the missing

tablets. He found table linens and silverware, two boxes of cigars, a portable DVD player, and a satellite dish—none of which he had approved for the trip. Men brought whatever they

wanted to the desert, but the satellite dish was going too far.

“Take this stuff out,” he ordered. “Don’t tell anyone. Just do it.”

“Where should I put it?” the assistant asked.

The sweat ran in rivulets down Nayir’s back. “I don’t care. Just make sure they don’t notice it’s missing until we’re gone.”

He took a handkerchief from his pocket and wiped his face. The garage, like many belonging to the superrich, was air-conditioned,

but it made no difference. The heat bled into everything. “And send a servant to buy salt!” These men were going to have daily

doses of salt tablets whether they liked it or not. He didn’t want them coming home on stretchers, dying of dehydration.

Nayir grabbed a water bottle and headed for the door. Behind him, twelve Land Rovers sat in regal formation, each attended

by detailers, fussed over by mechanics, lovingly attended like pashas of old by the eager hands of slave labor (this more

modern type of slave imported from Sri Lanka and the Philippines), and all for a five-day jaunt to the desert so that the

male half of a large and obnoxiously rich family of textile importers could later brag to their friends and neighbors about

shooting wild foxes, eating by a campfire, and generally “roughing it” at the edges of the Empty Quarter. The trip had originally

been planned for a fortnight, but because of the great chaos of schedules and commitments—each Amir son with his own boutique

to manage, investors to please, workers to boss around—their desert adventure had slowly been whittled down to five days.

Five. Nayir counted them in his head: Days one and two, to the desert. Day three, piss in the desert. Days four and five, drive

home.

He remembered the preparations for long-ago trips, taken to far more difficult locales in the company of greater men than

these. Packing sandbags and live pigeons for archaeological digs with old Dr. Roeghar and Abu-Tareq. “Why are we bringing

sand to the desert?” Nayir had asked, back then a boy of eight. “To give us ballast in case of a storm,” Dr. Roeghar had replied.

Nayir had not understood the word ballast, and he had had to refer to his uncle’s English-Arabic dictionary. When he finally understood, the idea conjured such a wild, windswept image

of the desert that he could hardly suppress his excitement. Then he reached the real desert, so treacherously hot that he

and the other children had to cover their faces for the first time, ingest water at ritual intervals like medicine, and discover

the indignity of salt tablets on the gastrointestinal system.

He’d worn his first pair of sunglasses that year and been teased by Abu-Tareq’s daughter Raja’ for looking American, so he’d

taken them off and never worn sunglasses again. Young, beautiful Raja’ with the bright green eyes. She swore that she’d marry

him someday, and he believed it, to his later, quiet embarrassment. During the day, they slept side by side in his uncle Samir’s

tent on an old mattress of straw that smelled incongruously green and chemical. Machines loomed above them, set on folding

wooden tables. He and Raja’ always curled up like twins, face to face, with dust on their cheeks and sand in their hair. They

locked legs sometimes, and once he tied pieces of string in her hair while she slept, and then tied the whole bundle with

a longer string to his own hair. Occasionally, when they woke, he’d find that her fingers had become entangled in his hair,

which was long and often knotted from the wind. The wind would wake them at dusk, and they’d hear the camp stirring, and the

coolness of the evening would beckon them outside. Entangled fingers would be forgotten as they raced off to play.

It was hard now to imagine that he’d once been so close to a girl, close enough to sleep on the same mat and call each other

“best friend.” At eleven, Raja’ had become a “woman,” and her mother had draped her in a veil and sent her off to be with

her sisters. He never saw her again. The next winter Dr. Roeghar’s dig had gone on without her, and Nayir soon became mature

enough to feel ashamed of any lingering thoughts of her face.

Nayir drank half the bottle of water and resisted the urge to pour the other half over his hair. Their Bedouin guide, Abdullah

bin Salim, was standing just outside the garage, unperturbed by the heat. He was staring at the traffic on the boulevard.

It was the same look he wore when studying the winter pastures of the Empty Quarter, a look of contemplation and challenge that said What do you have for me this year?

He frowned as Nayir approached. “Are you sure about this?” Abdullah asked.

Nayir wanted to remind him that he said that every year, no matter what kind of people they were taking to the desert. “I

have to admit,” he said, “they don’t seem ready.”

Abdullah didn’t reply.

“Listen,” Nayir said, “I’m sure it will be all right.”

Abdullah’s eyes remained on the boulevard. “How do you know them?”

“Through Samir. He’s known the father for twelve years.”

“These people aren’t Bedouin. They never were. Just looking at them, you can see they were sharwaya.” Sheepherders, not the “real” Bedouin, whose lives were tied to camels. It was an insult, but Nayir had heard this remark

before as well. The families they took to the desert were seldom good enough for Abdullah. And perhaps it was true that they

could never actually survive in the landscape their forefathers had inhabited for six thousand years, but in the greater scheme

of things, it was enough that they would try.

Nayir nodded politely. “You’re probably right. So let’s teach them how to be real Bedouin.” His cell phone rang again, and

this time he answered it. He listened patiently to his uncle, made a few replies, and once he was finished, excused himself

from the preparations and headed quickly to the parking lot for his Jeep.

As Miriam Walker made her way to the back of the plane, she could see that the flight to Jeddah was going to be tedious. It

was packed with holiday travelers. There were too many overhead items, too many nervous stewards scurrying down the aisles

looking for space. She looked back at her seat: 59C, the distance from the bowler to the kingpin. She felt a familiar combination

of dread and excitement. She was looking forward to seeing Eric again—she’d been gone for a month—but this simple walk down

the aisle marked a return to a world where she would stay indoors for weeks at a time. As the line trudged forward, she pushed

ahead, anxious to buckle herself in, as if the seatbelt would prevent her from stepping off the plane and turning her back

on it all.

Miriam’s seat assignment turned out to be next to a man. It seemed that Saudia ought to have restrictions against seating

women next to unrelated men, but apparently not. The man stared as she approached, a knowing look in his eye. He had the dark

eyes and olive skin of an Arab but a shock of natural blond hair. The contrast made him surprisingly handsome. Miriam’s cheeks

brightened. A sidestep put her behind a tall man in a turban. Slowly, casually, she straightened her shoulders and licked

her front teeth. Another brief glance told her he was still staring. They were technically in New York, but she could feel

Saudi Arabia draping over them with every blast of recycled air. She ran a hand through her hair and thought, Enjoy your last bit of freedom, curly locks.

She slid into her seat and shot him a casual smile, practiced to hide a crooked incisor. He greeted her with a satisfied look.

To stall his talking, she rummaged in her purse, made a show of forcing it beneath the seat in front of her, and spent a few

minutes inspecting the contents of the seat pocket. There she found a surprising comfort—a silk drawstring bag that must have been

left by the passenger before her. In it was a toothbrush, a bar of soap, a tortoiseshell comb, and a small bottle of Calvin

Klein perfume. Escape. She smirked.

As the plane backed out of the gate, Miriam felt herself tense. No going back now. She never used to be afraid of flying, but traveling to Saudi had done something to her. As they lumbered down the runway,

her instincts took over. Palms cold, forehead wet, chest tight. The plane would never go fast enough to rise off the ground.

Everyone stared at the windows and walls, which were shuddering violently. An overhead compartment burst open, spilling jackets

and a coffee tin on a passenger’s head. She wondered why anyone would take Folgers to Jeddah.

“Do you know,” the man beside her said, “on the old Saudia flights, they used to say Mohammed’s prayer for journeys over the

loudspeaker?” He spoke with a clear American accent, which surprised her somehow. She had thought he was Arab.

“Oh, really?” She gave a nervous laugh.

“Another tradition lost.” He seemed almost amused.

They felt the pull of their bodies resisting the rise. A man across the aisle began cursing. Miriam wanted to hush him but

she was hinged in a twilight of prayer, hoping they wouldn’t fall out of the sky. With a bounce, the plane leveled. It seemed

to stop in midair and float like a walrus on top of a balloon. A mechanical lullaby hummed in her head. It was midnight. That

and fear combined to make her feel crushingly tired. The only way to escape the terror of flying was to surrender to the void

of unconsciousness, but there was no alcohol on Saudia flights, and the dark nestle of sleep would not come closer until they

turned out the lights. She shut her eyes, hoping to deter her neighbor from starting a conversation, but he pressed the call

button. Bing. The steward appeared, looking annoyed. Her neighbor leaned past her, almost touching her breast with his shoulder. “Excuse

me,” he said. He asked for two empty cups.

“One for me,” he told the steward, “and one for my girlfriend.”

From the pocket of his jacket he produced two small bottles of wine. Miriam’s chest tightened.

“You know that’s—”

“Forbidden,” he said. “Yes. But what are they going to do, kick us off the plane?” He smiled at her, poured out two cups,

and tucked the bottles in the seat pocket. He gave one cup to Miriam. She shook her head but he insisted. “Come on,” he said,

“I’m sure the worst they’ll do is make us flush it down the toilet.”

She felt like a teenager again and found herself doing just what she’d done back then. She picked up the cup. “Thanks,” she

said, taking a sip. It was a welcome palliative. Actually, the worst they’ll do is arrest us and throw us in prison when we land.

“First trip to Jeddah?” he asked.

“No. My second.” Miriam saw the television flicker on, a big arrow showing the direction of Mecca and the time of the next

prayer: five hours away, local time. The stewardess came by with amenity kits, followed by a steward passing out coffee and

dates. Miriam quickly hid the cup beneath her tray table, but neither of them seemed to notice or care. “What about you,”

she said, “is this your first trip?”

“No. By the way, I’m Apollo.” His smile was teasing. “Apollo Mabus.”

“Great name.” She smiled back. “I’m Miriam.”

“Is that a southern accent I hear?”

“I’m from North Carolina.”

“Ah, I’m from New York.” He said it the way people say “checkmate.” She was a lesser species, Elvis perhaps, living in a trailer

on processed cheese and grits. The slight was so common, so predictable, that it might have been imagined, but her cheeks

flushed anyway and she hid the sting by taking a long sip of wine.

“And what do you do?” he asked.

“I’m a doctor.” She glanced at his reaction, saw his face stiffen, and decided she didn’t like him as much as she’d thought.

She certainly wasn’t going to clarify that she had a doctorate in music. “And you? You look like the academic type.”

He raised his eyebrows. “How’s that?”

“Well, you’re squinting, which means you probably left your glasses somewhere. And you’ve got a big callus on your third finger

and ink stains on your thumb.” He was trying to hide his discomfort with a look of amusement. The wine was warming her up.

“But you don’t seem the tweed jacket type, and those are some pretty big biceps, so tell me, what kind of academic pumps iron?”

“When you spend a lot of time at a desk,” he said slyly, “you need to do something to get the blood pumping.” She thought

it was a cheesy thing to say. She took another sip of wine.

“So what brings you to Saudi?” she asked.

He set his elbows on the armrests, and she watched him play with his watchband, turning it around his wrist by fourths. “I’m

a professor of Middle Eastern studies. My specialty is Quranic scripture. This trip is for research.”

“Ah.” The first rush of alcohol hit her, and she felt a wave of dizziness. Something on the TV caught her eye, and she glanced

up to see that the in-flight movie had been censored. Women’s arms and hair moved across the screen in blurred gray patches.

“What about you?” he asked. “What brings you to Jeddah?”

“My husband found a great job—”

“Of course.” He interrupted her with a smirk. “I didn’t think you’d be going into the country by yourself.”

Although she had just spent the past four weeks complaining loudly to her sisters, her father, her nieces, and anyone who

would listen about the miseries of being a kept woman in Saudi Arabia, she found herself prickling.

“I think it’s very brave of you,” he went on, “sitting it out in Saudi so that your husband can advance his career. Or are

you only in it for the money?”

“Both,” she said as flippantly as she could manage. It wasn’t strictly true. Eric had taken the job as a bodyguard—or rather

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...