China Boy

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

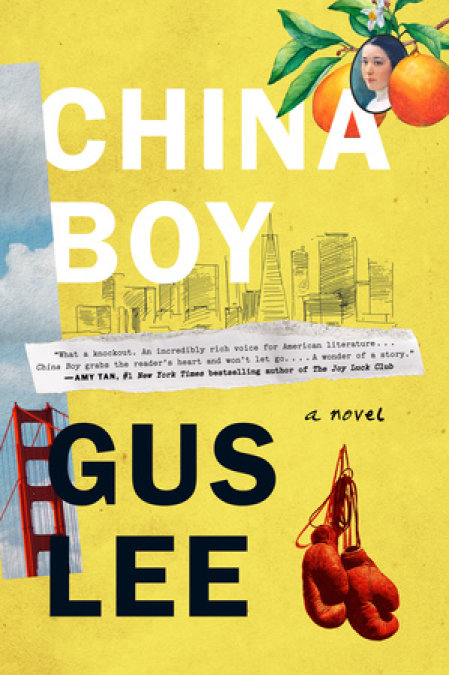

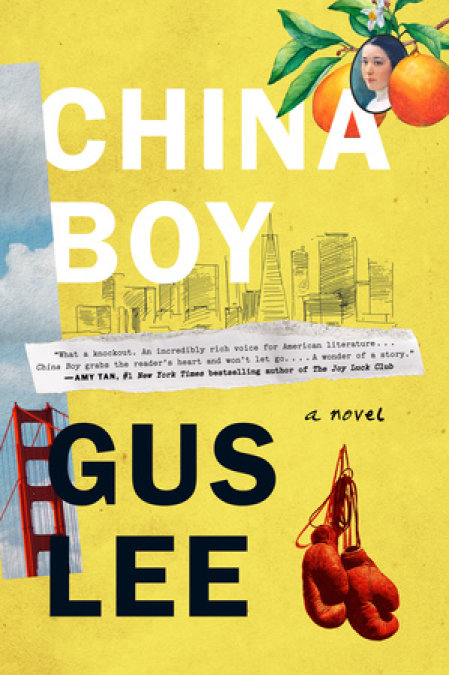

“What a knockout. An incredibly rich and new voice for American literature…China Boy grabs the reader’s heart and won’t let go.”—Amy Tan, bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club

“A fascinating, evocative portrait of the Chinese community in California in the 1950s, caught between two complex, demanding cultures.”—The New York Times Book Review

Kai Ting is the only American-born son of a Shanghai family that fled China during Mao’s revolution. Growing up in a San Francisco multicultural, low-income neighborhood, Kai is caught between two worlds—embracing neither the Chinese nor the American way of life. After his mother’s death, Kai is suddenly plunged into American culture by his stepmother, who tries to erase every vestige of China from the household.

Warm, funny and deeply moving, China Boy is a brilliantly rendered novel of family relationships, culture shock, and the perils of growing up in an America of sharp differences and shared humanity.

Release date: January 1, 1994

Publisher: Plume

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

China Boy

Gus Lee

“Stunning . . . Lee vividly portrays cultural conflict . . . he reminds us of Maxine Hong Kingston, both in his style and material.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“China Boy forcefully fills a gap long neglected in American literature—the strong, authentic voice of an Asian-American male.”

—David Henry Hwang, author of M. Butterfly

“EXTRAORDINARY . . . a fierce and passionate song of triumph over an alien landscape . . . alive with energy, despair, willpower and great tenderness . . . It is an exciting experience.”

—The Washington Times

“Resonating with strong characterizations, evocative descriptions of San Francisco in the 1950’s, and the righteous indignation of abused innocence.”

—Library Journal

“Gus Lee is one heck of a writer. He has a superb command of the language, of the lingo of the street and the Chinese-American argot.”

—Pittsburgh Press

“COMPELLING . . . This is the Chinese-American experience as Dickens might have described it . . . vividly and intensely human.”

—Publishers Weekly

“CONVINCING . . . OFFERS A VIVID GLIMPSE OF CHINESE-AMERICAN LIFE.”

—Kirkus Reviews

GUS LEE is the only American-born member of a Shanghai family. He grew up in San Francisco and attended West Point for three years until his failing performance in then-mandatory electrical engineering gave him the involuntary opportunity to become an enlisted man. After receiving his law degree from the University of California at Davis, he rejoined the army as Captain Lee and served as general counsel. He resumed civilian life to become a deputy district attorney in Sacramento, then served for some years as Director of Attorney Education for the State Bar of California. He is married and lives with his wife and two children in Colorado Springs. China Boy is his first novel.

GUS LEE

CHINA

BOY

A NOVEL

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Mah-mee, for love; to Father, for guidance; to my stepmother, for English; to my sisters, for caring.

To those who encouraged my work, with particular thanks to Lee Hause, Ying Lee Kelley, Mary Ming Zhu and Maralyn Elliott, to Susan Leigh and Alfred Wilks; to my peerless agent, Jane Dystel of Acton & Dystel and to Arnold Dolin, Vice President and Associate Publisher, and Gary Luke, Executive Editor; to Mrs. Marshall and Captain Piolonik, my high school and West Point English teachers; to H. Norman Schwarzkopf, whose faith in callow youth is still valued; to Bill Wood; and to HMR and MTH, who set the standard for excellence.

To the men and women staff and volunteers of the San Francisco Central YMCA, who ministered for low pay and long hours to the needs of youth: Karl R. Miller, Tony Gallo, Bruce Loong Punsalong, Bobby Lewis, Sally Craft, Dick Lee, Ken Cooper, Pete Joni, Don Stewart, Keith Gordon, Dave Friedland, George Wong, John Lehtinen, Leroy Johnson, Harry Lever, George McGregor, John Mindeman, Art Octavio, Buster Luciano Weeks, Dan Clement, Sherwood Snow, Dan Moses, Ralph and Lela Crockett, Lola and her cafe, and my other teachers and coaches of youth whose names could not be held as closely as the lessons they imparted. And to Toos, wherever you are.

And, to the Central YMCA Boys Department on Leavenworth—a place where all youth were of the same color, and every lad could be a hero. A place now so desperately needed, and now so sadly closed.

Table of Contents

1

CONCRETE CRUCIBLE

The sky collapsed like an old roof in an avalanche of rock and boulder, cracking me on the noggin and crushing me to the pavement. Through a fog of hot tears and slick blood I heard words that at once sounded distant and entirely too close. It was the Voice of Doom.

“China Boy,” said Big Willie Mack in his deep and easy slum basso, “I be from Fist City. Gimme yo’ lunch money, ratface.”

“Agrfa,” I moaned.

He was standing on my chest. I was not large to begin with; now I was flattening out.

“Hey, China Boy shitferbrains. You got coins fo’ me, or does I gotta teach you some manners?”

In my youth, I was, like all kids, mostly a lot of things waiting to develop. I thought I was destined for dog meat. Of the flat, kibbled variety.

In the days when hard times should have meant a spilled double-decker vanilla ice cream on absorbent asphalt, I contended with the fact that I was a wretched streetfighter.

“China,” said my friend Toussaint. “You’se gotta be a streetfighta.”

I thought a “streetfighta” was someone who busted up pavement for a living. I was right. I used my face to do it.

I had already developed an infantryman’s foxhole devotion; I constantly sought cover from a host of opportunities to meet my Maker. I began during this stage to view every meal as my last, a juxtaposition of values that made the General Lew Wallace Eatery on McAllister my first true church. Its offerings of food, in a venue where fighting was unwelcome, made my attendance sincere.

The Eatery was a rude green stucco shack. On one side was a bar named the Double Olive that looked like a dark crushed hat and smelled like the reason Pine Sol was invented. On the other flank was an overlit barbershop with linoleum floors in the pattern of a huge checkerboard.

The Eatery’s windows were blotched mica of milky greased cataract, its walls a miasma of fissured paint, crayoned graffiti, lipstick, blood, and ink. I always imagined that Rupert and Dozer, the Eatery’s sweaty, corpulent cooks, were refugees from pirate ships. They had more tattoos than napkins, more greased forearms than tablecloths. They were surly, they were angry, they were bearded and they were brothers, bickering acidly over what customers had ordered, over the origin of complaints or the mishandling of precious change; enemies for life, and so angered by countless hoarded and well-remembered offenses experienced and returned that no one would consider even arguing inside the Eatery, lest the mere static of disagreement spark a killing frenzy by the angry cooks.

“Flies, please,” I said to Rupert, who was the smaller, but louder, sibling.

“Fries! Crap! Boy, how long you bin in dis country? You bettah learn how ta talk, an’ you bettah have some coin, and don be usin no oriental mo-jo on me. Don job me outa nothin!” His voice churned like a meat grinder that had long been abused by its owner.

The Lew Wallace Eatery’s proximity to dying winos and artistic kids, its daunting distance from the Ritz, its casualness in differentiating dirt from entree—all were of no consequence to young folk who had tasted its fries and salivated to worship them again. Inside, food was ample, aromas were beguiling and my scuffed and badly tied Buster Browns were drawn like sailors to Sirens.

The Eatery was central to the nutrition of the Panhandle, but it failed to draw critics from the papers, gourmets from other nations, or gourmands from the suburbs. Passersby in search of phones, tourists seeking refreshments, the disoriented hoping for directions would study the Eatery’s opaquely cracked windowpanes, the cranky bulk of its grill managers, and steadfastly move on. The Eatery had not been featured in the convention bureau’s brochures. The Panhandle was the butt end of the underbelly of the city, and was lucky to have plumbing.

San Francisco is possessed with its own atmosphere, proudly conscious of its untempered and eccentric internationalism. With grand self-recognition, it calls itself “the City.” It is foreign domesticity and local grandeur. It is Paris, New York, Shanghai, Rome, and Rio de Janeiro captured within a square peninsula, seven by seven miles, framed by the vastness of the Pacific Ocean and the interior half-moon of satellite villages rolling on small hills with starlight vistas of Drake’s Bay.

The City’s principal park is the Golden Gate, a better Disneyland for adults than anything Walt ever fashioned. It has aquaria, planetaria, stadia, museums, arboreta, windmills, sailing ships, make-out corners, Eastern tea gardens, statues, ducks, swans, and buffalo. The park runs east directly from the Pacific Ocean for nearly half the width of the City, traversing diverse neighborhoods as blithely as a midnight train crosses state lines.

The Panhandle is where Golden Gate Park narrows to the width of a single block. It looks like the handle of a frying pan, and is almost in the dead center of the city. On this surface I came to boyhood, again and again, without success. I was a Panhandler. Panhandler boys did not beg. We fought.

A street kid with his hormones pumping, his anger up, and his fists tight would scout ambitiously in the hopes of administering a whipping to a lesser skilled chump. That was me. I was Chicken Little in Thumpville, the Madison Square Garden for tykes. It was a low-paying job with a high price in plasma. I had all the streetfighting competence of a worm on a hook.

Streetfighting was like menstruation for men—merely thinking about it did not make it happen; the imagined results were frightening; and the rationale for wanting to do it was less than clear.

Fighting was a metaphor. My struggle on the street was really an effort to fix identity, to survive as a member of a group and even succeed as a human being. The jam was that I felt that hurting people damaged my yuing chi, my balanced karma. I had to watch my long-term scorecard with the Big Ref in the permanently striped shirt. Panhandle kids described karma as, what go around, come around.

“Kai Ting,” my Uncle Shim said to me, “you have excellent yuing chi, karma. You are the only living son in your father’s line. This is very special, very grand!”

I was special. I was trying to become an accepted black male youth in the 1950s—a competitive, dangerous, and harshly won objective. This was all the more difficult because I was Chinese. I was ignorant of the culture, clumsy in the language, and blessed with a body that made Tinker Bell look ruthless. I was guileless and awkward in sports. I faced an uphill challenge with a downhill set of assets.

I was seven years old and simpler, shorter, and blinder than most. I enjoyed Chinese calligraphy, loved Shanghai food, and hated peanuts and my own spilled blood. It was all very simple, but the results were so complicated. God sat at a big table in T’ien, Heaven, and sorted people into their various incarnations. I was supposed to go to a remote mountain monastery in East Asia where I could read prayers and repeat chants until my mind and soul became instruments of the other world. I had a physique perfect for meditation, and ill-suited for an inner-city slum.

God sneezed, or St. Pete tickled Him, and my card was misdealt onto the cold concrete of the Panhandle, from whence all youth fled—often in supine postures with noses and toes pointed skyward.

Some who survived became cops, but more became crooks. We played dodgeball with alcohol, drugs, gambling, sharp knives, and crime. As children, we learned to worry about youth who held hidden razors in their hands and would cut you for the pleasure of seeing red. We avoided men who would beat boys as quickly as maggots took a dead dog in a closed and airless alleyway. The compulsion to develop physical maturity long in advance of emotional growth was irresistible. It caused all kids, the tough and the meek, the tall and the small, to march to the same drum of battle.

It was a drum tattoo that was foreign to the nature of my mother, but all too familiar to her life. This beat resonated with the strength of a jungle tom-tom in my father, but it ran counter to the very principles of his original culture and violated the essence of his ancient, classical education and the immutable humanistic standards of Chinese society.

Almost to a man, or boy, the children of the Panhandle became soldiers, until the Big Card Dealer issued a permanent recall, with the same result. Noses up.

As we struggled against the fates, Korea was claiming its last dead from the neighborhood, the ’hood, and Vietnam and every evil addiction society could conjure were on the way.

2

EARTH

My family arrived in San Francisco in 1944, in the middle of the most cataclysmic war the planet had ever suffered.

The family called the trip to America Boh-la, the Run, which is like thinking of the Hundred Years’ War as a pillow fight. The Run was a wartime journey across the Asian landmass, from the Yellow Sea to Free China, to the Gangetic Plains of India, across the Pacific Ocean to America.

Even today, this journey would be a hardship. In 1943, it was a darkly dangerous, Kafka-like venture into the ugly opportunities of total war. A million extremely hostile enemy soldiers blocked the thousand miles of twisting river road from Shanghai to Chungking. From there, with a major assist from American aviation, my family continued to India, and from India, with the help of the U.S. Navy, to the United States. It is the type of exercise where one hopes for more than a cold beer at road’s end. Since I was born in California, I missed the trip.

My family was not built for the road. My eldest sister, Jennifer Sung-ah, was fifteen. She was already tall, with long slender bones and a chiseled high-cheekboned face for which fashion models pray. She possessed unimpeachable status, for she was the Firstborn. She was resourceful, but was also a patriot, and experienced deep conflict in leaving China.

Megan Wai-la, my second chiehchieh, or older sister (tsiatsia in Mandarin), was twelve, and possessed of a charming and mirthful spirit. Megan Wai-la was as beautiful as the elegant Jennifer Sung-ah, but was poorly dressed. She possessed the strength of iron, for her pleasant disposition had been formed without the benefit of enduring care from our mother. Mother had, of course, wanted sons. A first daughter, with some good fortune, could be endured. But two daughters! This augured bad luck, and Mah-mee passed this ill fortune to the little baby girl who could be blamed for not being a son. Worn, secondhand clothes in a wealthy family were symbolic of a powerful devaluation.

Janie Ming-li was four, and enjoyed the dual status of being unbearably pretty as well as a near casualty of the diseases of China. She was at an age when crying was normal, but in a situation where a cry at the wrong time could draw a soldier’s gunfire.

In 1943 my mother and sisters were alone in a world at war. All they had to fear were Japanese Imperial troops, brigands, typhus, dufei: bandits, rapists, thieves, deserters, and the unclean. My father was a Nationalist Chinese Army officer and joined the family in San Francisco after V-J Day.

“Earth, wind, water, fire, iron,” said my mother. “This is what makes the world. I think I am earth. I crossed it, and became it, in the Run. I look at my fingernails, so clean, and still see the earth’s dirt in them. Farmers’ hands have soil embedded in the pores, so they are like the paddies. I can still feel the Boh-la in the little grooves in my fingers.”

My mother’s favorite belongings had been deposited into a crate that had been hauled across the world, defying the curiosity of interlopers and the efforts of thieves. It was a treasure trove of books, photos, clothing, and memorabilia.

Notice had come in the early morning of November 5, 1943: “Kampetai coming for the family of Major Ting Kuo-fan!” the short Salt Tax prefect cried breathlessly. “Tomorrow—dawn!”

The Kampetai, the intelligence arm of the Japanese Imperial Army, had identified Major T. K. Ting, Kuomintang Army, as an officer assigned to General Stilwell’s Rangoon Headquarters. He was now known to be running in the hills of Hupeh province with renegade American soldiers, shooting Kwangtung Army infantrymen. He was being sought by their gestapo in retribution for his warlike acts. Our dogs would be killed if they barked. Sons would be bayoneted and hung from poles, the women shot.

Mother turned to Paternal Grandmother, her mother-in-law. “Please. My respects to you, and my father. Please tell him I had no time to say good-bye. I must take my children from your home and seek another. Tell my husband!

“Tell him we will go upriver, to the Cheng clan in the Su Sung Tai. From there, Chungking. I would like, please, the old vegetable cart behind the tailor’s outhouse. Please tell Yip Syensheng that the wheels should be oiled. We leave before dawn.”

In that one tear-streaming night my mother and sisters tore through their belongings, putting all they could into the crate. Mementos went in, sacrifices came out, but the loss was not material. They were leaving the people of their blood and the home and hearth of their ancestors, and their efforts were like waving good-bye to the world. They were leaving everything, from love itself to the best kitchen staff and cook in the maritime provinces.

“How can this be?” my mother asked.

“Everything beneath Heaven is disturbed,” whispered Da-Ma, her sister-in-law, who was higher in rank and therefore possessed the answers. Their children cried as they said good-bye to each other, fearing the eternal loss of irreplaceable friendship, dreading death and the loss of the clan’s lineage.

When the cocky roosters called forth that morning, sitting atop empty dog kennels, my mother and her three daughters were already five hours upriver, stirring cool road dust with the chef’s finest provisions and the house’s best guard dog in the cart.

Jennifer, my eldest sister, looked forward to reaching Free China, and even America beyond, with the fierce determination common to the young in 1940s China. She did not want to leave the most exciting city in Asia, but her duty was to Mother.

Father had been born in 1906, six years after the foreign powers had seized Beijing in the Boxer Rebellion. Two years after his birth, the Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi died, leaving P’u-yi, the infant Last Emperor on the throne of the Empire of China. P’u-yi and my father had been born in the same month of the same year, in the last dynasty in Chinese history. When my father was five, the Empire fell, and the warlords appeared. After the popular student democracy movement of 1919, my father’s mother, who ran the Shanghai Salt Tax Companies Office in the name of her husband, foresaw a Western-influenced future. She promoted a younger man to be house interpreter and chief of tutors.

He was Luke Hung-chang. He was from Fukien province, was missionary-trained, and had bright, penetrating eyes. All my sisters remembered that. He spoke English, French, and German, was a ferocious reader, and represented the hope of a new China. He gave my sisters their Western names on their last night at home.

“Sung-ah, I give you the name Jennifer. It is very classy, very tremendously musical! A name Amadeus Mozart would have composed!” said Tutor Luke, smiling while tears glazed over his fiery eyes.

“Wai-la, close your eyes and listen. Listen to this sound: Megan! Is that not dramatic, and beautiful! A name of love.

“Wai-la. It is a tremendously special name. And your honored mother appreciates the effect of name-changing. It will bring you her affection, and change your yuing chi. It is an excellent name change! I will think of it, and the sound of it, as you wear it in Free China!”

The tears now streamed down Tutor Luke’s cheeks, the dark comma of his forelock continuing to fall into his glistening eyes. He knew their chances of reaching Chungking were not good. If they succeeded, he also knew that Major Ting wanted the family in America, a place he would never go. His duty was in China.

Chinese men are only allowed to shed tears when the cause is great. He was losing the girls of his dreams. My sisters remembered his passion that night, and how his tears and hair fell as relentlessly as his hopes. He knelt before his smallest student.

“Syau Ming-li. Little Ming-li. I name you Janie, the name of an empress queen of Yinggwo, England, the name of strong and good women of foreign literature. No one pushes around a Janie! So! Remember to keep your head tall, and straight. I expect you to remember me, and to keep this name. This would honor me, Bohbohbei, Little Precious.

“Say it,” he whispered.

“Jen-nii,” she said, sadly, reaching forward, touching his tears.

“Remember me, my beautiful students,” he whispered.

In the vegetable cart that was their transport, Megan, drama in her name and cursed with being Second Daughter, looked back, fearing a future without the greater family’s protection from an uncaring mother. She was twelve.

Jane, four years old and not to be pushed around by anyone, slept in our mother’s arms.

Mr. Yip, the barrel-chested horsemaster with a German self-loading Mauser in his belt, spat on the road as they left the delta, heading for the danger of Japanese lines, the hope of sanctuary with our clan’s allies, the Chengs of the Su Sung Tai, and the heady promise of Free China near Chungking.

My mother wept silently, not looking back to the east. She turned to the north, to her father in Tsingtao. She carried an unpaid debt of shiao, piety to parent, in her breast, as heavy and as foreboding as the rock of Sisyphus.

She also carried a wealth in diamonds, pearls, and rubies in the lining of her clothing. Smaller gems had been sewn into the jackets and pants of her daughters. The thumbs and fingers of my mother’s and sisters’ hands were numb with the accidental prickings of the desperately rushed needles. The jewels were their passports to safety in a world gone mad.

Mother feared that Father would never find them, wherever the fates compelled them to stop. The world was insane, and very big, the Yangtze longer than the Great Wall itself.

I later asked Megan about their flight from China.

“Oh, Little Kai, it was frightful, and horrid. The fear was—hateful. Mah-mee cut off all our hair, smudged us with charcoal, bound our chests, dressed us like peasant boys. We pretended to be stupid as we hiked the Yangtze gorges so men would not look at us.”

“Why no want men look at you?” I asked.

“It took six months,” said Jennifer from across the hall. Megan licked her lips and shook her head, her long hair shimmering in the light from the bright ceiling lamp in her room. She loved having as many lights as possible illuminated. “We really were in terrible danger,” she said. “Mah-mee wore a butcher knife on her forearm, tying it against her, like this,” showing how it lay on the inside of her left arm, always within reach. “She threw it at bandits once. We were always frightened. Then we lived with the Gungtsetang, the Share Wealth Party, for over a month. Mother convinced them that we were peasants, and they accepted us.” Megan peered into the distance.

“It was safer with them than to be on the road. But we left the Share Wealth village for the Nationalist capital in Chungking.”

The Gungtsetang were the Reds—the communist enemies of our father and General Chiang Kai-shek. I could not understand it. “We saw so many people who were going to die.” Her fingers rustled through the hair on my head. “Father met us near Wuhan. He said to Mah-mee: ‘I know you; you never give up,’ and he gave us troops to escort us to Chungking, but they were killed. Dufei, bandits, and tuchun, warlord soldiers, attacked us. That’s when Mah-mee threw the knife. Ayy,” she concluded.

They had bounced and swayed in the old, unpainted cart, clutching the crate, listening to the hooves of the horse, ignoring the men on the river road, hearing the rippling tides of the Yangtze as it rushed to the sea, the dog barking anxiously at his new world.

“Quiet, dog,” said Mr. Yip. He evaluated the road people. Refugees, spies, thieves, misplaced farmers, homeless, hopeless. He curled his eyebrows and his lips, promising death for their interference, placing the menace of his guardianship into their fantasies of finding wealth in the crate.

One of the best prizes of the redwood crate was a book written by Mother’s tutor for her. Years later, she pulled it out to show me.

“See,” she said, “the character, Tang, my tutor. Oh, son. He was so wise, so deep. He always wanted to train a prodigy to become the tallest scholar in Chingsu, the Forest of Brush Pens, in the imperial capital. Instead, he got a girl who could never take the examinations. And I revere his memory because he also taught me about Mozart.”

My mother wept for him. As she related this family history to me, I twitched and rubbed her arm, which only made her cry louder. I asked her the key question about the escape story.

“Yip Syensheng and doggie kill bad guys?” I asked.

“Here is the character, Mar,” she continued wetly, “my family, and Ahn Dai, my name then. The book explains the great philosophers K’ung-Fu-tzu, Lao-tzu, Meng-tzu from a female viewpoint.” Later, I learned that K’ung-Fu-tzu was known in America as Confucius, which is as East Asian a name as DiMaggio.

“You change names, Mah-mee?” I asked. My mother’s name was Dai-li.

“Oh, yes, My Only Son,” she said, sniffling and giggling and pulling my ear. “We change names at our pleasure. For foo chi, good luck, or for better luck. Luck is everything. Foo chi is controlled by gods and spirits. Only clan names and family titles, like Mother and Oldest Daughter and Father and Uncle and Auntie and Firstborn’s Tutor, are unchangeable, for these ranks were established by the gods themselves in the beginning of time.

“Your father has had many names. He was such a dashing, handsome rogue at Taoping Academy that he had a series of them, each from a different teacher. I changed my name only once. When the first Japanese sentry at Hangchow Gate outside Tungliu asked where we were taking my crate and pressed his long knife into Megan’s face.”

“You care for Megan?” I asked.

Mah-mee’s face said: Wrong question.

“Father name, real name?” I tried.

“Of course it is. It is the last one he adopted at the academy. It came from his college roommate, from the powerful Cheng clan, of the Su Sung Tai up the Yangtze gorges from Shanghai. Father now works for the daughter of the Chengs.”

“Where Yip Syensheng? Where doggie, Mah-mee?”

She shook her hand at me, since the horsemaster’s fate remained unknown, but he was a powerful, smart, and resourceful man. He was a survivor. He was probably shoeing a horse as we thought of him.

“What doggie name, Mah-mee?” I asked.

“Name? He was a dog. His name was Dog,” she said.

“Doggie live, Mah-mee?”

“The guard dog ran away in Free China. Tsa, tsa! You are so much a boy, worrying about a dog! He salivated constantly after the Run, and peed on everything in Chungking everytime the Japanese bombed us.”

As I grew older and came to see fighting as a way of life, I wished that I had been born earlier, so I could have participated in that grand odyssey. My father understood that sentiment, but it made my sisters think me daft. In many ways, as a child, I prepared myself for an epic test, an adventure that would measure my worthiness to be the only son of the American extension of the Ting clan.

The Panhandle and the Haight, our mirror ’hood south of the park, were standard-issue wartime blue-collar districts where shipyard workers and longshoremen returned after back-busting, long-shift days at Hunters Point and Fort Mason. The Handle and the Haight were in the sunbelt, unique San Francisco districts without fog, thunderstorms, or people of Chinese or Caucasian descent.

When I arrived squalling—no doubt prescient about my imminent fate—the streets were half black. By the time I was in the second grade and in the center of the frying pan, I was the only Asian, the only nonblack and the only certified no-question-about-it nonfighter in the district. Black families, tired of being hammered by the weight of history and pressured by the burden of being members of the wrongly hued tribe in Georgia and Mississippi, were heading west armed with hope

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...