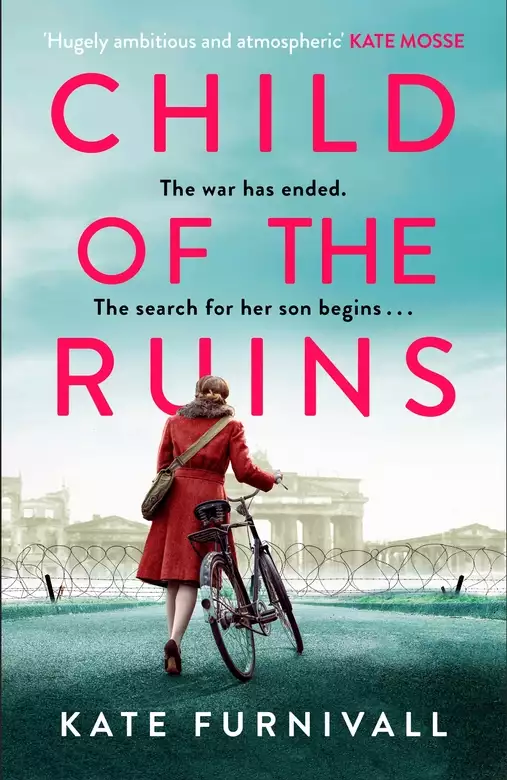

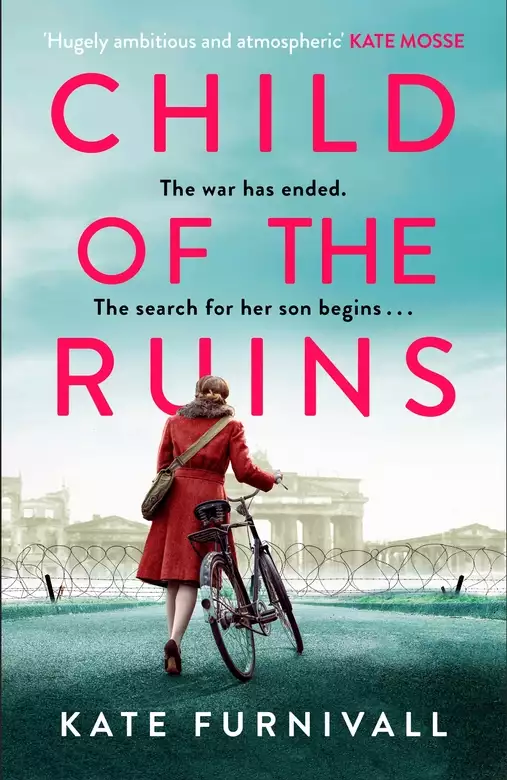

Child of the Ruins

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Anna and Ingrid have survived World War II. Now they must live through the Berlin airlifts.

Evocative and unforgettable, CHILD OF THE RUINS is set during the Berlin air lifts of 1948 and written by one of the most brilliant writers of historical fiction in the UK.

People are disappearing. I spoke to my neighbour yesterday, we laughed at some nonsense, and today he is gone. We only discovered he was missing because the dog wouldn't stop howling and we all knew he would never leave his beloved pet. So I am careful, extremely careful.

Two families divided by war.

An entire city on the edge of disaster.

1948, Berlin. World War II has ended and there is supposed to be peace; but Russian troops have closed all access to the city. Roads, railway lines and waterways are blocked and two million people are trapped, relying on airlifts of food, water and medicine to survive. The sharp eyes of the Russian state police watch everything; no one can be trusted.

Anna and Ingrid are both searching for answers - and revenge - in the messy aftermath of war. They understand that survival comes only by knowing what to trade: food; medicine; heirlooms; secrets. Both are living in the shadows of a city where the line between right and wrong has become dangerously blurred. But they cannot give up in the search for a lost child ...

Praise for Kate Furnivall's writing:

'Kate Furnivall has a talent for creating places and characters who stay with you long after you have read the final word' JANE CORRY

'Hugely ambitious and atmospheric' KATE MOSSE

'Fast-paced with a sinister edge' THE TIMES

(P)2023 Hodder & Stoughton Limited

Release date: October 31, 2023

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Child of the Ruins

Kate Furnivall

BERLIN, 1945

ANNA

There are only three people in Berlin who know i killed a man. And not just any man. A Russian, an officer in the Red Army. One with fancy boots and even fancier medals on his chest.

There are only three people in Berlin who know I killed a man. My mother. My friend Kristina. And Martha Dieleman. These are the three. They know that I didn’t just shoot the bastard or even stick a knife between his ribs. They know I picked up a broken brick off the filthy ground in one of Berlin’s back alleyways and pounded his head to a pulp till my hands were sticky with his blood and whatever he’d had for brains was trailing from my fingers. That’s why I am here, alive, cycling up and down the grey and decimated streets of Berlin, and he is not.

The war is over. But the unspoken war of whispers, of midnight arrests and tortured body parts rages on unseen. I honestly believed I’d have learned to forget the killing by now, to roll the memory of his scream into a tight little wad and toss it away to rot among the piles of rubble that were stacked high in Berlin’s streets.

Yet that killing still breathes deep inside me like a living thing. I feel it curled up behind my ribs, hidden away under my shabby brown coat where no one can see it. No one, that is, except me. Each morning I take my hard grey pumice stone and I scrub at a spot in the exact centre of my breastbone to rid myself of the stain of it. I scour it raw again and again. Yes, I know the scrubbing is pointless because the killing has sunk too deep into the very bones and sinews of who I am. It is a part of me now.

But I say this, so you know: the Russian deserved to die.

‘Where is he?’

I open my eyes. The darkness and the cold in the room are pressing down on me like something solid, trapping me. I can’t breathe right. I drag in icy Berlin air but it feels as if it is packed full of tiny needle-sharp fishhooks that catch in my throat and snag on the inside of my lungs. I try to cough them up but it is like coughing up glass. I force myself to sit up. I spit out blood.

‘Where is he?’

I begin to panic.

‘Where is he? Where is he?’

Is that my voice? It sounds hoarse and scraped raw. My words hang unheard in my bedroom, and I can tell I am in my own narrow bed because my fingers are gripping the silky animal warmth of the sable coat that I throw over at night to fight the cold. A ribbon of ice-white moonlight unfurls across the floorboards where Felix’s crib should stand. It is gone.

‘Where is he?’ This time I scream it.

I throw back the bedcover and am shocked by the effort it takes, my arm is shaking, and beneath me the sheet smells of stale sweat and vomit. It dawns on me that I am sick. And I am alone.

I get myself as far as the door of my room and am forced to lean against it, clinging to the doorknob to keep me on my feet. I ache. My whole body aches and my lungs are on fire, but none of it matters. It is fear that has dragged me from the depths of God-knows-where. It is fear that flares into an inferno, consuming the room. Consuming me. The fear that she has stolen my child.

I open the door. I listen. Silence.

It was the silence that had finally woken me. There were no cries, no sweet chuckles, no hungry whimpers. No snuffling snores. Nothing.

How long? How long had I lived in silence?

I don’t know.

Hours? Days? Weeks? How long have I been sick?

I light the stub of the candle in an old candlestick that stands on a table by the door – we have no electricity supply at this hour. I make my way into what used to be the large drawing room of our apartment, before the Soviets came and carved it up into a pokey miserable living space. It lies in total darkness. I raise the candle to scour every corner of the room. The flame creates shadows that writhe away from me as though I am the one to fear, but I find nothing until a sudden swirl of light at the other end of the room sets my heart racing.

‘Felix!’ I whisper.

But it is a mirror, the moving light is a reflection of my own candle. For a moment I stand there, shaking, then I rush to my mother’s bedroom door and throw it open. It slams against the wall behind and rebounds, almost knocking me to the ground.

‘Mutti!’ I shout and storm in.

Except the shout is more of a rasp and the storming is more of an unsteady hobble, but inside my head I shout and storm and demand the truth from my mother.

‘Mutti, where is he?’

‘Where is who?’

‘Felix.’

She is sitting bolt upright in bed, startled, a picture of wide-eyed innocence. She wears a high-necked white silk nightdress and her long hair is scooped together by a white ribbon and hangs neatly over one shoulder in an immaculate braid. Her face is thin, her cheekbones jutting out under pearly skin, and her lips set tight with annoyance at this intrusion. My mother is a woman of fifty but in the swaying dim light of my candle she has the soft untouched appearance of a young girl, except for the look in the intense blue of her eyes. There you can see it. You can see exactly who she is.

‘Get out, Anna,’ she says.

I move forward past the stacks of furniture, avoiding the tottering footstool propped atop the carved Black Forest chairs that had once been my father’s favourites. She is frightened that I will burn them for firewood, so she guards them in here. I reach my mother’s bedside and look down on her, while I hold the candlestick high. Whenever I look at her eyes, I see his. Whenever I look at her mouth, I see his. I wonder now how she can face me and ask, Where is who?

‘What have you done with my baby?’ I demand. ‘Where is my Felix?’

She blinks slowly. It has always been her way of making someone wait, even Papa if he was trying to hurry her. I can’t wait.

I try not to shout. ‘Mutti, Felix is only three months old. It is winter and he will die if he is out in the cold. Where is he?’

‘He has gone.’

‘Gone where?’

‘Away.’

‘What do you mean, away? Away where?’

‘You were too ill with pneumonia to care for the little bastard and he wouldn’t stop crying. I got rid of him. You know I never wanted him here, not from the very beginning. He was tainted. He brought shame on our name, we both know that. He’s gone.’

‘Where?’

I was shaking so hard the candle flame guttered and would have extinguished itself if my mother had not removed it from my grip and placed it on her bedside cabinet. With the same cold hand that had removed my son.

‘You almost died, Anna.’

‘Where?’

I lean down over her and it is only when I see a drop of moisture fall on her silk nightgown and spread tendrils through its fibres that I realise I am crying. The wind claws at the shutters and I think of Felix somewhere out there without me.

‘Tell me, Mutti.’ I seize her arm, nothing but bird bones, hollow and fragile. ‘Tell me what you did with him?’

‘I gave him away.’

‘To whom?’

‘To the first person who would take the brat.’ She pushes me aside and swings herself out of bed. She stares glassy-eyed at the empty vodka bottle next to the candlestick instead of at me. ‘He’s gone, Anna. He’s been gone more than a week and I have no idea where or with whom, so don’t bother asking. Forget him. This city is crawling with unwanted children. You’ll never see him again.’

‘Is he still alive?’

I have visions of her lowering her pillow over his precious sleeping face and burying his limp body in the rubble of the city, while I lay burning with fever, soaking the sheets of my bed.

‘I have no idea,’ she says and I can hear the truth of it in her voice. ‘He’s gone. Accept it.’

Something breaks inside me, something vital that I had believed was unbreakable, and I know it cannot be mended.

‘His crib? His toys?’

‘I burned them,’ she says. ‘Like the Russians burned our city.’

I cannot bear to breathe the same air as her any more; rage is suffocating me and I leave the bedroom with images in my head that I cannot bear to look at. I am in the dark. Pitch dark. In our living space I cling to the icy window frame and press my forehead tight against its blackness as an ocean of grief sweeps through me and I recall the final terrifying Russian bombardment of Berlin. In April outside our city the Soviet Union assembled the largest force of military power ever seen, and Russian Marshal Zhukov inflicted enormous casualties and crippling damage to gain the glory of capturing the prize of Berlin. He grasped our poor city in a death grip. So now we live under Russian control, much of the time in darkness and in freezing cold because the winter is here. We have no lighting other than candles and oil lamps, or firelight if we’re lucky, because oil is worth more than gold in Berlin. But right now none of this means a thing to me.

‘Felix, my sweetest heart,’ I whisper. ‘Somewhere you are out there. Somewhere in this godforsaken city you are alive, I can feel your heart beating within mine.’ I force myself to believe my own words. ‘I love you and I will find you, my child, I swear it. Wait for me. I will come.’

CHAPTER TWO

BERLIN, 1948 NEARLY THREE YEARS LATER

ANNA

‘Halt!’

The shout made me jump. A harsh Russian voice.

I jammed on the brakes of my bicycle. My front wheel skidded across a cobweb of ice on the road, the threadbare tyre devoid of grip, and I had to slide my weight backwards to hold the rear end down. It was December and the sky hung low, laden with unspilled snow. Ice had gathered in the shadow of the massive columns of the Brandenburg Gate that dominated Pariser Platz at the junction of Unter den Linden and Ebertstrasse. Only one block to the north stood the obscene mangled wreckage of the Reichstag that had once housed our proud German parliament, but which now was a constant reminder of what we’d lost.

The bored Russian soldier at the checkpoint that marks one of the crossing points dividing East Berlin from West Berlin swaggered towards me in his grubby Red Amy uniform, and I felt the familiar twist of unease in my gut. It’s what they like to see. The submission of the vanquished. Berlin’s inhabitants were permitted to pass back and forth between the Soviet sector and the Allied sectors of the city, but not freely. Each time we were required to show our identity papers at the checkpoints and were prohibited from carrying forbidden items. So I settled one foot on the cobbles, lowered my eyes and halted.

I had learned to obey.

Berlin had learned to obey.

‘Halt!’ the voice at the checkpoint ordered again and addded in Russian, ‘Bystro!’

I’d heard the order clearly despite my woollen hat pulled down tight around my ears against the cold. Above me in the pot-bellied clouds the relentless drone of America’s Skymaster planes and the British RAF’s Yorks could be heard, as they continued to circle down in their all-day and all-night spiral into Berlin’s Tempelhof and Gatow airports, bringing life-giving food and fuel to sustain the inhabitants of blockaded West Berlin.

This Russian guard was tall and cumbersome inside his thick brown winter greatcoat and ushanka hat with its cosy ear flaps. His boots crunched the ice underfoot and his eyes were half shut, as though he had no desire to open them wide enough to view Berliners in any detail.

‘Wait,’ he ordered.

I waited. I stood beside my bicycle, resting my hands on the rusty handlebars. I stood there, trying not to grip, trying to appear bored too, keeping any trace of panic off my face.

‘Papers?’ He stretched out his hand.

I obeyed. His gaze skimmed over my name but then flicked on to me and stayed there. Something pulsed into life in my gut. Give a man a uniform and a rifle and a reason to hate and it changes him, though this one looked as if even as a child his idea of fun would have been tearing heads off Moscow’s pigeons.

‘Where you going?’ He spoke German but with a heavy Russian accent.

‘To visit a friend.’

‘Where?’

‘On Ku’damm. That’s the Kurfürstendamm boulevard in the western sector of Berlin.’

He frowned, his forehead creasing into well-worn grooves. ‘Do you carry food into the western sector of the city for your friend?’

‘No, of course not, that would be against the law.’

‘Open your coat.’

I propped the bicycle saddle against my hip, fumbled with my buttons and held my coat wide open. The icy wind was bitter yet I could feel sweat gather in the notches of my spine. The Russian removed his gloves and his hands searched for hidden contraband under my armpits, between my breasts, tucked into my waistband. I stood still as stone. I am not brave. For good reason. During the three and a half years of the Soviet Union’s occupation of the eastern sector of Berlin, I’d seen what happened to brave people. They were shot.

‘I am carrying no forbidden contraband on my bicycle. No food. No lumps of coal. No candles,’ I stated in a flat voice. ‘I obey the law.’

I stepped back, keeping hold of my saddle, but the guard’s hand followed me and gripped the handlebars.

‘You call this piece of shit a bicycle?’

I minded that he called my Diamant bicycle shit. It grieved me to see the state of it now. But that was the point, the bald tyres and the rusting metalwork – to look like something that no one else would want. This checkpoint guard with the cavernous nostrils could smell something wrong though. Was it me? Was it the bicycle? Was it my fear?

His attention shifted to the leather saddlebag slung on the back of the bicycle. ‘Open it,’ he ordered.

I undid the buckle. Inside lay a bicycle spanner, a coiled spare chain and a puncture repair kit, because the city’s ravaged roads shredded tyres. He prodded at the chain before raising the rear end of the bicycle a fraction off the ground, testing its weight. I held my breath. I knew if I ran now, he’d put a bullet in my back.

A thin wail of despair rose into the grimy air, startling us both. For a second I feared it had spilled out of my own mouth, but no, it came from the young woman standing a few metres away. She wore a bottle-green coat and peony-pink headscarf, and she was staring at a grey duck egg balanced on the palm of a second Soviet guard at the checkpoint.

‘Please,’ she begged. ‘Please, don’t take the egg from me. It’s for my son.’ Her voice was trembling. ‘He’s sick. He needs it … please …’

She held out her hand, her eyes pleading. Her face was thin but lovely, the way bone china is lovely, her features delicate, her skin taut and translucent. It was the kind of face people turned to look at, but here if you look too lovely, these men get greedy. Behind her a line of people had formed, people with stiff blank faces, trying to hide their eagerness to cross into the west if only for a few hours, patient figures well accustomed to queueing in the cold because in the Soviet sector we have to queue for everything.

A Russian military vehicle rumbled past, too close to a plodding horse and cart, and I saw the cart driver turn and swear silently, but otherwise the traffic across Pariser Platz was sparse except for the rattle of trams. Just ahead of us loomed Brandenburg Gate, a triumphal arch flanked by two gatehouses and crowned by a bronze Quadriga chariot driven by the goddess of victory. Ironically she was blown to bits in the war.

The other guard was older, his eyes kinder, but my bastard guard stalked over and jabbed his comrade’s elbow so hard that the egg went spinning off his hand. It hit the ground with a smack and the shell shattered. The yolk slithered intact on to the cobbles, a bright splash of orange in this grey colourless world. Quick as a cat the young woman sank to her knees, scooped up the yolk between both hands and slipped it into her mouth. She jumped to her feet, her large blue eyes fixed warily on the soldiers.

We all knew she hadn’t swallowed.

With a sour smile my guard swung out his arm and caught her hard across the throat. She recoiled, clutching her throat, a violent retching sound rising out of her because the blow had forced her to swallow. No one spoke as tears gathered in her eyes.

‘Go now, Fräulein,’ the older guard said.

She turned and ran with long angry strides that carried her across Pariser Platz, past the burnt-out Hotel Adlon, once the grandest hotel in all Berlin. The blackened remains were located in the heartland of the handsome government ministries and embassies, but like the Reichstag, it was a lesson about the fragility of life in the city. Nothing is safe. The young woman made her way out of the Soviet sector and into the British sector of Berlin, her green coat flapping behind her. The guards lost interest in me and waved my bicycle through with impatience to clear the line.

When you do something enough times you get hardened, don’t you? Like layers of hard skin forming between the experience – whatever it may be – and the soft edges of yourself. So why didn’t it happen to me? I’d waited and waited for it. Why didn’t crossing the border from one half of the city to the other ever get easier, from the Russian eastern sector, where I lived, to the western sectors controlled by the Allies? Why did it feel as though I was walking on broken glass with bare feet? Why did I always look for a pair of dove-grey eyes that were never there?

I swung up on my saddle and cycled past the large sign that read You Are Now Entering The British Sector. I breathed. I was in West Berlin.

I caught up with the running figure in a side street, the peony-pink headscarf easy to spot. It was one of those streets where the tall elegant buildings on one side were still standing, admittedly with chunks knocked out of them, bullet holes scarring the walls, and most of the glass in the windows missing, but definitely still habitable. On the opposite side the landscape had been flattened to vermin-infested rubble, though someone must have been living among the ruins because a string of washing fluttered like a white flag between the outcrops of what had once been a staircase, its brass handrail long gone.

‘Wait,’ I shouted.

The peony headscarf stopped running. I braked alongside it, abandoned my bicycle and seized her narrow shoulders. It was like holding a skeleton, not a scrap of flesh on it, nothing but fragile bones. I gave her a shake.

‘Kristina, what the hell do you think you were doing back there?’ I demanded. ‘You scared the life out of me.’

‘You told me to distract the guards.’

‘Yes, but I meant with your smile. With your charm. Not with a bloody egg in your pocket. You know it’s against the law to carry food from the Soviet sector into the west of the city. You could have been arrested, you fool. You could have been shot.’

My fear for her tasted slick at the back of my throat. I drew her close and hugged her to me, then stepped back so that I could take a proper look at her.

‘Is your throat okay?’ I asked.

It didn’t look okay. A dull claret bruise was already forming.

I heard Kristina sigh. ‘You don’t have to worry about me, you know,’ she said.

‘Yes, I do.’

She leaned forward, kissed my cheek and smiled. She was good at smiling. She used to practise in her mother’s dressing-table mirror when we were young, trying different ones on her face for size. Kristina Fischer and I had gone through our school years together, arms linked, digging each other out of scrapes, watching each other’s back. When I think about it, we were an odd pairing. I was the sporty type, living on my bicycle, swimming in the Wannsee or building secret hideouts in Tiergarten, my limbs the colour of honey. Whereas Kristina, well, ever since I could remember Kristina had yearned to be an actress. She’d dolled us both up in makeshift costumes at every chance, me hot and sweaty in my mother’s mink coat, while she took the starring roles in the extravagant scarlet velvet opera cape she would sneak out of my mother’s wardrobe.

But in 1939 the war came. We were sixteen. It sucked the oxygen out of our world. So instead of becoming an actress, Kristina went to work in a munitions factory and married a soldier who was a war cameraman. His name was Helmut and he was crushed to death by an American Sherman tank in the Battle of Aachen four years ago.

On the pavement with her now I waited while an old man hurried past, his head ducked against the grit that the wind snatched from the ruins and hurled in our faces. Grinding grit with our back molars had become a daily occupation for Berliners. I lowered my voice because even here in West Berlin walls listened, windows watched, doors opened a crack.

‘How is Gerd?’ I asked softly.

‘Worse.’

‘I’m sorry. Give him a kiss from me. And this too.’

I propped my bicycle against the wall and we both crowded round it, shielding the saddle from the view of any casual observer. Using the spanner from the saddlebag, I gave the screws under the seat a few twists, and the saddle came loose. I removed from inside it a roll of greaseproof paper and a small brown bottle of tablets, both of which I tucked into my friend’s coat pocket.

‘Thank you,’ Kristina whispered.

‘Aspirins,’ I said. ‘I wish there were more.’

‘They’ll help Gerd. They’ll ease his pain.’

Gerd was her son, my godson, and I adored him. He had a broken wrist, poor kid. He was only six years old and though he was slight like his mother, he had a big heart beating in his skinny little chest, and golden curls that I couldn’t keep my hands off. The two of them were living in a tiny one-bedroom apartment in the remnants of Müllerstrasse in West Berlin where you’d have to sell your grandmother to obtain even the simplest medication right now.

‘Go home to Gerd,’ I told her. ‘Thanks for your help.’

Though Kristina lived in West Berlin, like many Berliners she worked as a maid most days at a smart hotel that had been taken over by the Soviets in East Berlin, which meant she had to pass through a checkpoint twice a day to get there and back. She was paid a pittance, but her luminous smile could earn her tips from the wealthy Soviet elite who now stayed in its luxurious rooms. They were pampered and petted, and savage as bears.

Instead of leaving, Kristina leaned against the wall and the dark circles under her eyes stood out against her flawless skin like grubby thumbprints.

‘There are slices of wurst for you both rolled up in the greaseproof paper,’ I told her.

A spark leapt into her blue eyes. ‘Thank you,’ she mouthed, though no sound emerged.

I stood her up straight, rubbed her arms to bring warmth back into them, rubbed them hard because I wanted to rub the sadness away. I took hold of my bicycle’s handlebars again, but she wound her thin fingers around my wrist.

‘Good luck,’ she said.

‘Thanks, I’ll need it.’

Word had gone out that the Americans were hiring today for jobs out at Tempelhof airport.

‘Don’t forget there will be a load of people going for whatever jobs are on offer.’ Kristina gave me a quick inspection and I saw her open her mouth to question my dowdy mouse-brown coat, but she shut it again and snatched the peony-pink scarf from her head. She tied it around my neck. ‘That’ll get you noticed,’ she laughed, but then said uneasily, ‘Be careful, Anna. Trust no one out there. We both know there are paid informers everywhere.’

‘Oh, Kristina, you don’t trust anybody.’

‘I trust you,’ she said and then she was gone. The green coat without the peony scarf was running away up the street.

Above my head the heavy aircraft engines continued to roar. The Russian blockade of West Berlin had turned the city into a prison.

CHAPTER THREE

BERLIN, 1948

INGRID

A knife flew through the air. A brief blink of sunlight caught its blade as it slammed into the wood only a hair’s breadth from Ingrid Keller’s left cheek.

Go to hell, Fridolf. Too close. Far too close.

Another blade came at her.

A roaring started up in her ears like a mini whirlwind. She forced her face into a paper-thin smile but her stomach jammed in her throat. When you have an expertly honed metal tip tearing into the large circle of wood on which you’re tied, you run out of smiles fast.

Another thud. Another. Missing her by no more than a sliver of spit. One slit her sleeve. The next nicked her buckskins. Her mind was now spinning so fast, her vision blurred and she no longer knew which way was up and which way was down as the knives flashed and streaked and raced towards her. Scheisse!

Fridolf. No.

One whirled flashily, haft over tip, and cut into the wood at a spot midway between her legs with such force that she felt the board vibrate.

Enough.

A drum roll. She held her breath. The final blade parted her hair.

Mein Gott!

It was that close.

The small crowd that had gathered to watch the performance in one of West Berlin’s public squares whooped and clapped their appreciation. The ragged kids oohed and aahed wide-eyed and drew in their collective breath with gasps of amazement. That was always good. The more the audience gasped, the more they were happy to throw some money in the hat. The entertainment gave the onlookers a giddy pleasure because it wiped out, even for a few blessed minutes, the struggles of their day. It lifted the corner of the misery around them like the edge of a blanket and allowed them to forget. Allowed them to laugh. Ingrid was proud of that.

She knew that Fridolf was the best knife thrower in all of Germany, but her heart was still crawling around somewhere in her cowboy boots when he winked at her and brought the circus Wheel of Death to a halt. He loosened the rope loops that fastened her wrists and ankles to the gold-painted wheel that had been spinning her round and around while he hurled his knives at her. She slipped free. She stood on firm ground, swaying like a drunk, and took a bow with a showy flourish for the audience.

There had to be an easier way to earn a living.

They had set up that day – without a licence – in Breitscheidplatz, a huge public square right in the centre of West Berlin, one of the busiest stops on the U-Bahn. It sat at the southern tip of the Tiergarten park and the zoo, just off Kurfürstendamm, and was a great catch-all for shoppers crossing the square to queue with their ration books. The square had been decimated by bombing during the war, its life and soul pummelled to a stinking black dust until all that remained of its classy eighteenth-century buildings was the all-too-familiar heap of rat-ridden rubble piled high and the painful sight of the Kaiser Wilhelm Church at its centre. Except that now the church – an extravagantly Romanesque affair with five pointed spires – was no longer a church, it was a set of broken teeth.

Everyone loved a circus. It had always struck Ingrid as wonderful that people seemed to be born with a desire for its magic, and before the war Ingrid’s father had owned one of the best circuses in the state of Brandenburg. Big top, aerialists, animals and clowns, yes, the whole star-spangled package – she’d been a highwire artiste herself – and she’d loved growing up among performers stinking of sawdust and greasepaint. Disbanded now. Gone. Ever since her father’s death in one of Rommel’s Panzer tanks in the African desert. But she still popped up in the city with snippets of what was left of the circus whenever she could get away with it. Berliners loved to watch the next best thing to a full-scale circus and that was a scary knife-throwing act.

The danger to Ingrid wasn’t faked. Her heart rate was proof of that. But – for now – it was over. She breathed again and took another bow as the sky righted itself and settled back into its God-given place above her.

‘One of these damn days you’ll take my eye out, Fridolf,’ she growled at him as they acknowledged the applause.

‘One of these damn days you’ll learn that I never miss my mark.’ He grinned at her.

‘To hell with you,’ she grinned back. ‘Those knives had my name on them today. I could hear them whispering to me.’

Fridolf chuckled. His thick tangle of black hair was worn tied back from his lined face, dark suspicious eyes as sharp as his blades. He was probably not far off fifty, small and wiry, and she couldn’t remember a time in her life when Fridolf hadn’t been around, utterly devoted to her father as well as to the circus animals. At the end of each day he’d never rolled himself up in his blanket without first rubbing heads with each of the big cats, and he’d wept like a newborn baby when there was no money left to feed them.

For the knife act, he and Ingrid always dressed in cowboy outfits for no good reason other than that audiences seemed to love to see her in tight, fringed buckskins. It got them excited. So now she grabbed her upturned Stetson and darted in and out of the crowd, collecting the few pfennigs they could spare. Novembers in Berlin were like the tremors that come with a dose of winter flu, they seeped into your bones, but Berliners were hardened. Standing around for hours on freezing cobbles outside sparsely stocked shops, clutching their ration books, was a daily pastime if you wanted to eat. Berlin could be cruel.

‘You got something for me, soldier?’ she urged.

With her Stetson begging bowl in her outstretched hand, Ingrid made a beeline for a figure in US military uniform. The Americans were best. More generous than the Brits because they were paid more. This one

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...