- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

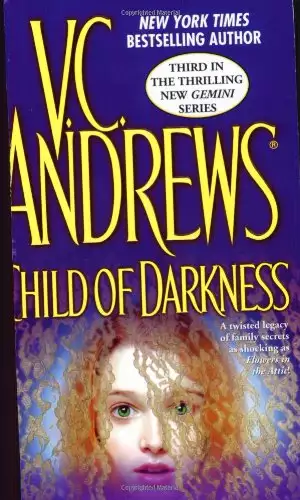

She grew up in the shadows of lies. Now the past will come to light. As a child, she was Baby Celeste, the one thing that kept her mother in touch with reality. But now her mother is in an institution, and sixteen-year-old Celeste Atwell is alone in the world. Adopted by a wealthy couple, Celeste has everything a girl could desire: designer clothes, luxury cars, even a handsome boyfriend. But her indulgence may come at a steep price -- because the secrets hidden within her new family are too dangerous to keep under wraps.... Also in the bestselling Gemini series from V.C. Andrews®-- be sure to read Celeste and Black Cat, available from Pocket Star Books!

Release date: January 1, 2005

Publisher: Pocket Books

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Child of Darkness

V.C. Andrews

I wouldn't go until I had brushed my hair. Mama always spent so much time on my hair while Noble sat watching, as if he were jealous and wanted to be the one to brush it. Sometimes I let him, but he would never do it in front of Mama because of how angry it would make her. He would make these long, deliberate strokes, following the brush with his hand because he needed to feel my hair as much as see it. As I looked at myself in the mirror, I could almost feel his hand guiding the brush. It was hypnotizing then, and it was hypnotizing to remember it now.

"Mother Higgins said right now," Colleen Dorset whined and stamped her foot to snap me out of my reverie. She was eight years old and my roommate for nearly a year. Her mother had given birth to her in an alley and left her in a cardboard box to die, but a passerby heard her wailing and called the police. She lived for two years with a couple who had given her a name, but they divorced, and neither wanted to keep her.

Her eyes were too wide, and her nose too long. She was doomed to end up like me, I thought with my characteristic clairvoyant confidence, and in a flash I saw her whole life pour out before me, splashing on the floor in a pool of endless loneliness. She wasn't strong enough to survive. She was like a baby bird too weak to develop the ability to fly.

"Where that baby bird falls out of the nest," Mama told me, "is where she'll live and die."

Some nest this was, I thought.

"Celeste, you'd better hurry."

"It's all right, Colleen. If they don't wait, they don't matter," I said with such indifference, she nearly burst into tears. How she wished there was someone asking after her. She was like someone starving watching someone in a restaurant wasting food.

I took a deep breath and left the small, almost claustrophobic room I shared with her. There was barely enough space for the two beds and the dresser with the mirror above it. The walls were bare, and we had only one small window that looked out at another wall of the building. It didn't matter. The view I had was a view I owned in my memory, a view among others I gazed back at the way people peruse family albums.

The walk to the headmistress's office suddenly seemed longer than ever. With every step I took, the inadequately lit hallway stretched out another ten. It was as if I was moving through a long, dark tunnel, working my way back up to the light. Just like Sisyphus in the Greek myth we had just read in school, I was doomed never to reach the end of my long and difficult climb. Each time I approached the end, I fell back and had to begin again, as though I were someone caught in an eternal replay, someone tormented by wicked Fate.

Despite the act I put on for Colleen, as soon as I was told I was to meet with a married couple who might want to become my foster parents and perhaps adopt me, my heart started to thump with anticipation. The invitation to an interview came as a total surprise; it had been years since anyone had any interest in me, and I had just celebrated my seventeenth birthday. Most married couples coming to the orphanage look for much younger children, especially ones just born. Who would want to take in a teenager these days, especially me? I wondered. As one of my counselors, Dr. Sackett, once told me, "Celeste, you have to realize you come with a great deal more baggage than the average orphan child."

The baggage wasn't boxes of dresses and shoes either. He was referring to my past, the stigma I carried because of my unusual family and our history. Few potential foster parents look at you as your own person. It's not difficult to see the questions in their eyes. What bad habits did this one inherit? How has she been twisted and shaped by her past, and how are we going to handle it? Why should we take on any surprises?

None of this was truer for anyone than it was for me. I had been labeled "odd," "strange," "unusual," "difficult," and even "weird." I knew what rejection was like. I had been nearly adopted once before and returned like so much damaged goods. I could almost hear the Prescotts, the elderly couple who had taken me into their lives, return to the children's protection agency and, as if speaking to someone in a department store return and exchange department, complain, "She doesn't work for us. Please give us a refund."

Today, perhaps because of this new possibility, that entire experience rushed over the walls of my memory, where it had been kept dammed up for so long. It pushed much of my past over with it as well, so that while I walked from my room to the office to meet with this new couple, the most dramatic events of my life began to replay. It was as if I had lived and died once before.

Truthfully, I have always felt like someone who had been born twice, but not in any religious sense. It wasn't that I had some new awakening after which I could see the world in a different light, see truth and all the miracles and wonders that others who were not reborn did not see. No, first I was born and lived in a place where miracles and wonders were taken for granted, where spirits moved along the breezes like smoke, and where whispers and soft laughter came out of the darkness daily. None of it surprised me, and none of it frightened me. I believed it was all there to protect me, to keep me wrapped comfortably in a spiritual cocoon my mother had spun on her magic loom.

We lived in upstate New York on a farm that had belonged to my family for decades and legally still belongs to me. I was a true anomaly because I was and remained an orphan with an inheritance, property held in trust and managed by my mother's attorney, Mr.

Deward Lee Nokleby-Cook. I knew little more about it, but more than one headmistress or counselor had shaken her finger at me and reminded me I had far more than the other orphans.

The reminder wasn't made to make me feel better about myself. Oh no. It was meant to encourage me to behave and obey every rule and every command, and was usually held over my head like some sort of branding iron. After all, property, having anything of value, meant more responsibility, and more responsibility meant you had to be more mature. If they had it their way, I would have completely skipped my childhood -- not that a childhood in an orphanage was anything to rave about, anyway. I wish I could forget it all forever, every moment, every hour, every day, and not have it all come up inside me like so much sour milk.

Despite the fact that I was a little more than six when I left the farm, I still remembered it quite vividly. Perhaps that is because my time there was so dramatic, so intense. For most of my infancy, I was kept under lock and key, hidden away from the public. Even though my mother thought my birth was a miraculous wonder, or perhaps because of that, my birth was guarded as the deepest, most treasured family secret. I was made to feel like someone very special. Consequently, the house itself for nearly my first five years was my only world. I knew every crack and cranny, where I could make the floor creak, where I could crawl and hide, and where there were scratches and nicks in the baseboard, each mark evidence of the mysterious inhabitants who had come before me and still hovered about behind curtains or even under my bed.

For most of my life at the farm, I was taken out after dark and saw the world outside in the daytime only through a window. I could sit for hours and hours and stare at the birds, the clouds, the trees and leaves swaying in the wind. I was mesmerized by all of it, the way other children my age were hypnotized by television.

I had only one real companion, my brother, Noble. My cousin Panther was just a baby then, and I often helped care for him, but I was also jealous of any attention he stole from my mother and brother, attention that would have been directed at me. Right from the beginning, I resented it when he and his mother, Betsy, came to live with us.

Betsy had lived with us before. She had moved in soon after her father married Mother. I was never quite sure if he was my real father as well, but immediately he wanted me to call him Daddy. He died before Betsy returned. She had run off with a boyfriend, and she didn't even know he had died. The whole time she was away, she had never called or even written a letter to tell her father where she was, but when she returned and learned of his death, she was very angry. I remember she blamed us for her father's death, but she was even angrier about the way her inheritance was to be distributed. The air in the house felt filled with static. Mother stopped smiling. There were ominous whispers in every shadow, and those shadows grew deeper, darker, and wider every passing day, until I thought we would be living in darkness and no one would be able to see me, even Noble.

Before Panther's mother, Betsy, had invaded our home and spoiled our lives, I had Noble completely to myself. He was the one who took me out, the one with whom I worked in the herbal garden and took walks about our farm when I was finally permitted to be out in the daytime. Often he read with me in the living room and carried me to my bedroom to put me asleep. He taught me the names of flowers and insects and birds. We were practically inseparable. I felt he loved me even more than my mother did. I was so sure that someday I was to understand why; someday, I would understand it all.

And then one day he disappeared. I can't think of it any other way or of him as anything but who he had been to me. It was truly as if some wicked witch had waved her wand over him and in an instant turned him into the young girl I had been told was my half sister, Celeste, after whom I had been named. I had seen pictures of her many times in our family albums and heard stories about her, describing how bright she was, how pretty. It would be years before I would understand it, and even then I would wonder if everyone else was mistaken and not me. However, I would learn that my mother believed it was Celeste who had died in a tragic fishing accident, and not Noble, her twin brother.

Eventually and painfully, however, I would discover that it really was Noble who had drowned. Mother refused to accept it. She forced Celeste to become her twin brother, and all I knew about Celeste now was that she was in a mental clinic not far from the farm. As I said, I would make many shocking discoveries about myself and my past, but it would take time. It would be a long, twisted journey that would eventually bring me back to my home, to the place where all this began and where it was meant to come to a finalization, when I would truly be reborn.

I have been told that when I was brought to the first orphanage, I was a strange, brooding child whose demeanor and piercing way of looking at people drove away any and all prospective adoptive or foster parents despite my remarkable beauty. Even though I was advised to smile and look innocent and sweet, I always wore a face that belonged on a girl much older. My eyes would get too dark and my lips too taut. I stood stiffly and looked as if I would just hate to be hugged and kissed.

Although I was polite when I answered questions, my own questions made the husbands and wives considering me for adoption feel very uncomfortable. I had the tone of an accuser. More than once I was told I behaved as if I knew their deepest secrets, fears, and weaknesses. My questions were like needles, but I couldn't help wondering why would they want me. Why didn't they have children of their own? Why did they want a child now, and why a little girl? Who wanted me more, the man or the woman? They might joke or laugh at my direct questions, but I wouldn't crack a smile.

This sort of behavior on my part, alongside my unusual past, would sink the possibility of any of them taking me into their home. Even before the interview ended, my prospective new parents would look at each other with no written in their eyes and make a hasty retreat, fleeing me and the orphanage.

"See what you've done," I was often told. "You've driven them away."

It was always my fault. A child my age shouldn't ask such questions, shouldn't know such things. Why couldn't I just keep my mouth shut and be the pretty little doll people hoped I was? After all, I had auburn hair that gleamed in the sunlight, bright blue-green eyes, and a perfect complexion. The prospective parents were always drawn to me and then, unfortunately, repulsed by me.

At the first orphanage, where I remained until I was nearly ten years old, I quickly developed a reputation for clairvoyance. I always knew when one of the other girls would get a tummy ache or a cold, or when one would be adopted and leave. I could look at prospective parents and tell if they were really going to adopt someone or if they hadn't yet decided to take on such a serious commitment. There were many who were just window shoppers, making us all feel like animals in a pet shop. We were told to sit perfectly straight and say, "Yes, ma'am," and, "Yes, sir."

"Don't speak unless spoken to" wasn't only written over doorways; it was written on our brows, but I wasn't intimidated. There were too many voices inside me, voices that would not be still.

My first orphanage caregiver was a strict fifty-year-old woman who demanded we all call her Madam Annjill. As a joke, I think, her parents had named her Annjill, just so they could laugh and say, "She's no angel. She's Annjill." I didn't need to be told. She was never an angel to me, nor could she ever become one.

Madam Annjill didn't believe in hitting any of us, but she did like to shake us very hard, so hard all of us felt as if our eyes were rolling in our heads and our little bones were snapping. One girl, a tall, thin girl named Tillie Mae with brown habitually panic-stricken eyes the size of quarters, really had so much pain in her shoulder for so long afterward that Madam Annjill's husband, Homer Masterson, finally had to take her to the doctor, who diagnosed her with a dislocated shoulder. Tillie Mae was far too frightened to tell him how she had come to have such an ailment. She was in pain for quite a number of days. The sight and sound of her crying herself to sleep put the jitters into every other orphan girl at the home, every other girl but me, of course.

I was never as afraid of Madam Annjill as the others were. I knew she wouldn't ever shake me as hard. When she did shake me, I was able to hold my eyes on her the whole time without crying, and that made her more uncomfortable than the shaking made me. She would let go of me as if her hands were burning. She once told her husband that I had an unnaturally high body temperature. She was so positive about it that he had to take my temperature and show her I was as normal as anyone.

"Well, I still think she can make herself hotter at will," she muttered.

Perhaps I could. Perhaps there were some hot embers burning inside me, something I could flame up whenever I wanted to and, like a dragon, breathe fire at her.

I must say she worked hard at finding me a home, but it wasn't because she felt sorry for me. She simply wanted me out of her orphanage almost as soon as I had arrived. Sometimes I overheard her describing me to prospective foster parents, and I was amazed at the compliments she would give me. According to her I was the brightest, nicest, most responsible child there. She always managed to slip in the fact that I had an inheritance, acres of land, and a house kept in trust.

"Most of my little unfortunates come to you with nothing more than their hopes and dreams, but Celeste has something of real value. Why, it's as if her college education or her wedding dowry was built into any adoption," she told them, but it was never enough to overcome all the negative things they saw and learned.

"Where are her relatives?" they would inevitably ask.

"There aren't that many, and those that there are were never close. Besides, none of them want the responsibility of caring for her," was Madam Annjill's reluctant standard explanation. She knew what damaging questions her answers created immediately in the minds of the people who were considering me. Why didn't her relatives want her? If a child had something of value, surely some relative would want her. Who would want a child whose own relatives didn't want to see hide nor hair of her, land in trust or no land in trust?

I wondered how valuable the farm really was. Of course, in my memory, the house and the property remained enormous. After all, it was once the whole universe to me. For years I believed that not only were the house and the land waiting for me, but all the spirits that dwelled there were waiting as well. It would be like returning to the womb, to a place where there was protection and warmth and all the love I had lost. How could anyone put a value on that? I wanted to grow up overnight so I could return. When I went to bed, I would close my eyes and wish and wish that when I woke in the morning, I would be a big girl. I would somehow be eighteen, and I could walk out of the home into a waiting limousine that would carry me off to the farm, where everything would be as it once was.

What would I really find there? I believed my mother was gone, buried, and my only living immediate relative was in a mental home. The attorney might hand me the door keys, but wouldn't I be just as lonely and lost as ever? Or would the spirits come out of the woods and out of the walls and dance around me? Wouldn't they all be there, my mother included? Wouldn't that be enough company? It used to be enough for me, Mama, and Noble.

Why weren't the spirits coming for me now? I would wonder. Why weren't they appearing in the orphanage at night to reassure me and tell me not to worry?

As mad as it might seem to the other girls, I was longing to hear whispering, see wisps of people float by, feel a hand in mine and turn to see no one there.

Eventually, I did. Noble was there with me.

"Hey," I remember him calling to me one night. I opened my eyes and saw him. "You didn't think I would accompany you to this place and then just leave you here and forget you, did you?"

I shook my head, even though I had believed that. Seeing him again was too wonderful. I couldn't speak.

"Well, I'll be around. All the time. Just look for me, especially if anything bothers you, okay?"

I nodded.

He came closer, fixed my blanket the way he always did, leaned over, and kissed me on the forehead. Then he walked into the darkness and disappeared.

But I knew that he was there, and that was the most important thing of all.

I saw him often after that.

"Whom are you talking to?" Madam Annjill would ask me if she caught me whispering. "Stop that right now," she would order, but then she would cross herself, shake her head, and mumble to herself about the devil having children as she quickly fled from the sight of me.

I knew she was watching me all the time. Noble would know it too and warn me.

"She's coming," he would say.

"Whom are you looking at so hard, and what are you smiling about?" Madam Annjill would demand at dinner if I stopped eating and stared into the corner where Noble was standing, his arms folded, leaning against the wall and smiling at me.

I didn't reply. I turned to her ever so slowly and looked at her, not a movement in my lips, not a blink of my eyes. She would huff and puff and shake her head and reprimand some other poor, homeless little soul who had washed ashore on her beach. No solace here, I thought. No one waiting with open arms. No welcome sign over this front door. No one to tuck you in and kiss your cheek and wish you a good night's sleep. No one to tickle you or smother you with kisses and embraces and flood your eyes with smiles.

No, here the sound of laughter was always thin and short, cut off quickly like the sound of something forbidden. Where else did children our age feel they had to choke back happiness and hide their tears? Where else did they pray so hard for a nice dream, a sweet thought, a loving caress?

"Oh, the burdens, the burdens," Madam Annjill would chant at visitors or to her husband, referring to us. "The discarded burdens, someone else's responsibilities, someone else's mistakes."

She would turn and look at us with pity dripping from her eyes, crocodile tears.

"That's what you all are, children. You've been cast away like so much worthless riffraff," she would moan with the back of her hand pressed to her forehead like some terrible soap opera actress. "I will try, but you have to help me. Clean up after yourselves. Never make a mess. Never break anything. Never disobey me. Never fight or steal, and never say anything nasty."

What about the nasty things she would say to us? I wondered. Why did she want to run an orphanage in the first place? Was it only for the money, or did she enjoy lording it over helpless young girls and seeing the fear and the gratitude in their eyes?

At night she walked past our bunks and inspected, just hoping to spot some violation, no matter how small. Everyone but me would have her head turned away, her eyes closed, holding her breath and praying Madam Annjill did not find anything wrong and assign some punishment or shake her. Only I would lie there with my eyes wide open, waiting for her. I wasn't afraid. Noble was standing beside me, waiting, too.

She would stop, even though I sensed she wanted to keep going and avoid me. After all, she had to hold on to her authority. She had to pause and snap at me.

"Why aren't you trying to sleep?" she would demand.

I didn't answer. I glanced at Noble, who shook his head at her and then smirked at me.

Dealing with my silence was far more troublesome and difficult for her than the whining others did, or the poor little attempts to escape blame. Silence had always been my ally, my sword, and my shield.

Madam Annjill would look at Noble, whom I knew she couldn't see, and then she would simply nod at me.

"You know you were hatched from an egg of madness, don't you? If you're not careful, it will grow inside you, and you'll end up like your mother and your sister."

I didn't say a word. I stared at her until she walked away, muttering to herself.

Only then did I turn to Noble and show my unhappiness.

"Can't we go home?" I whispered.

"No, not yet," he said. "You have to be patient, very patient, but I promise you, Celeste. Someday you will go home again."

"Take me home now. Please. Take me home," I begged. He brushed my hair and told me to be patient again, and then he walked into the darkness.

Actually, I had no idea where home was anymore, or even what it was. It was just a wonderful word, a word that rang with hope.

Home.

Surely Noble is right, I thought. I will return, and everyone who has loved me will be there waiting with open arms. Surely they've missed me as much as I've missed them.

After all, I could still hear their screams of pain and agony as the car and the social workers took me away that dreadful afternoon. Even now, nearly ten years later, the memories of how I was scooped up and taken away from the farm and the only life I had known were painful. I remembered those agonizing days in terms of colors, red being the most prominent. I was so full of anger then. Why had Noble gone after Celeste appeared? I'd wondered, wearing a scowl like a permanent mask. It was all Betsy's fault, I'd decided. Somehow, it was because of her that he was driven away. I'd been happy she was dead, and I wanted to see her buried and gone from sight.

If I tried really hard to recall specific moments about that last day, I felt my insides tightening up, as if all my organs were being woven into knots around my heart.

It was far worse immediately after I had been taken. Then I would actually have a hard time breathing, what the doctors diagnosed as an emotional seizure. In fact, during the first few months after I was separated from the only people I had known and loved and loved me, I would often fall into a sleep so deep and long, it resembled catatonia.

Sleep was, after all, a way of turning my face away from ugly reality, but even sleep wasn't a total escape. A stream of nightmares would flow through my head: Noble being pushed back into his grave, Betsy with a twisted smile, laughing at me after she died, Mama glassy-eyed and cold, her lips squirming like earthworms. I would eventually wake screaming, and no matter what anyone said or how lovingly they treated me, I never lost the sense of foreboding, a sense that something dreadful was following me, sometimes disguised as my own shadow. I still felt it now, even at seventeen. I had the habit of glancing into corners, looking back every once in a while when I walked. I knew it drew attention to me, but I couldn't help it. Something was there. Something was always there. I didn't care if people thought I was still a mental case.

There is no way to avoid revealing that I was brought to a children's mental clinic almost immediately after being taken from the farm. I do vividly remember a beautiful woman with light brown hair and soft green eyes. She was tall and stately with an air of authority about her that made me feel confident, as confident as a baby in her mother's arms.

She was, I would learn, a pediatric psychiatrist, although she never wanted me to call her Dr. anything, just Flora. There would be others. In the beginning Flora spent hours and hours with me trying to get me to speak, to tell her why I was so angry. She knew most of it by then, of course. She had learned how my mother had died in her sleep and had been left in her bed, how my sister had accidentally killed Panther's mother, Betsy, on the staircase and then buried her in the herbal garden. Soon after, Noble's grave was uncovered as well, and the whole story of our twisted turmoil spilled out into the community like untended milk boiling over the edges of a pot.

I would learn that people came from faraway places to look at the farm, to talk about all of us with local people. Newspaper articles turned into magazine articles, and someone even wrote a book about it. At the time there was even some talk about a movie being made. We were that infamous.

Ironically, the community that had once considered us pariahs had suddenly embraced us. Everyone was anxious to tell about an experience with us, and of course with every retelling the exaggerations grew, until the truth was as lost as youth and innocence.

Flora worked very hard with me, and eventually she got me to talk and tell her the things she wanted and needed to know. She was always reassuring me. The truth was, I wanted to talk to someone badly. Noble hadn't come with me into that place. I was totally alone, so eventually telling Flora some of my secrets gave me relief. I could feel the weight slowly being lifted off my brow and the smiles beginning to return, first with a tiny movement at the corners of my mouth and then in my eyes. I so wanted to learn again, to read, to listen to music and stories. My appetite returned, and I didn't have to be forced or convinced to eat. I came out of the darkness as if I had been released from prison.

It was then that she brought me together with children my age, and over time the past became less and less oppressive. I celebrated a birthday at the clinic. They made me a nice party, and Flora bought me a beautiful pink dress with lace trimming about the sleeves and hem. My emotional seizures became far and few between and eventually disappeared entirely.

In a way I was sorry I had gotten well. My healing, my return to a normal life, meant I was ready to be discharged. I had come to live for Flora's visits and talks. Now the prospect that I would never see her again was a blow that almost drove me back to catatonia. I had gone from clinging to one skirt to clinging to another. Whom would I cling to now? Who would be there for me? The outside world was truly outer space to me. I would surely dangle or float aimlessly.

Flora knew my fears. "It's time you got on with your life, Celeste," she told me one morning in her office. "You have nothing to be afraid of anymore. You're a very, very bright little girl, and I'm sure you're going to be successful at whatever you want to do later."

"Am I going back to the farm?" I asked her.

"No, not yet. Not for a long time," she said.

She rose from her chair and looked out the window in silence for so long, I thought she was deciding whether or not to take me home with her. In my secret heart of hearts, where I dared treasure hopes and dreams, that was my most precious. If she had done so, how different my life would have been, I often now thought.

She turned and smiled at me, but I saw the disappointing answer in her eyes, in the film of sadness that had been drawn over them. This was the beginning of a good-bye that would last forever. Someday her face would drift back into my sea of memories, gradually sinking deeper and deeper until it would never again surface.

"First, you are going to a place where you will live with other little girls much like yourself," she explained. "It's a home managed by a nice couple, the Mastersons. You will finally go to a real school, too, and on a school bus

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...