- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

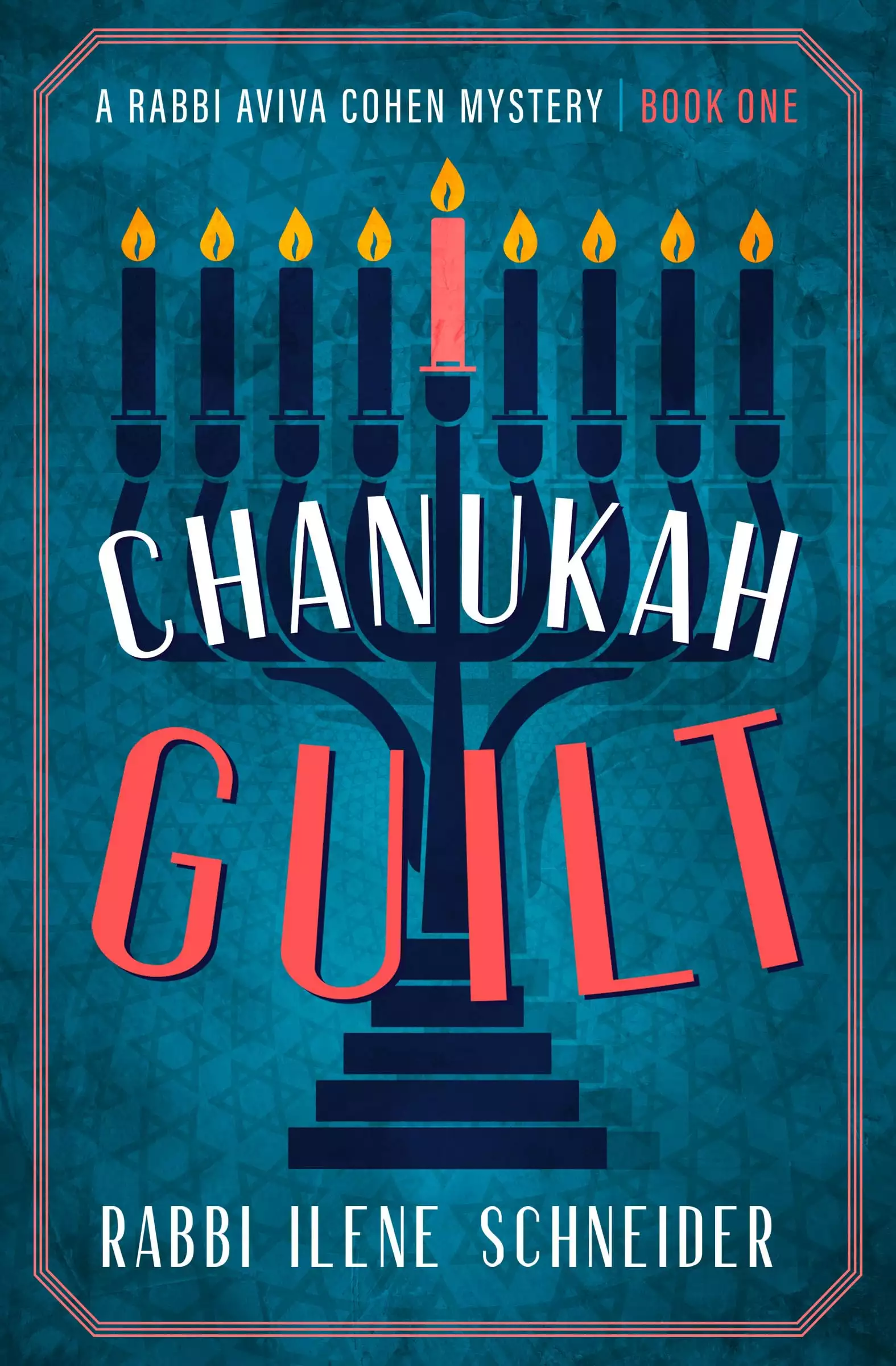

A small-town New Jersey rabbi is compelled to investigate when a funeral leads to a suspicious death in this cozy mystery series opener.

Aviva Cohen is a fifty-something, twice-divorced rabbi living an uneventful life in southern New Jersey. Although her family is unconventional, her days are otherwise routine. Services, religious education, and counseling mostly. She also officiates the occasional funeral . . .

But the funeral of unpopular real estate tycoon William Phillips is very out of the ordinary. At the end of the service, two family members ask Aviva for help, saying that Phillips was murdered. Aviva dismisses their claims but is shocked when one of them is later found dead from an apparent suicide.

Riddled with guilt and suspicious of the death, Aviva puts her skills as a yenta to good use. Her search for answers, unfortunately, has her crossing paths with her first ex-husband, the new chief of police. Plus, if Aviva’s not careful, the next funeral she attends might be her own . . .

“Lots of fun!” —Midwest Book Review

“Schneider succeeds in blending the complex life of a congregational spiritual leader with that of [a] first-rate detective, family member, confidant, friend, human being and even yenta (nosy body).” —San Diego Jewish World

“Chanukah Guilt weaves Jewish culture and mystery in a delightful blend. . . . I enjoyed this cozy mystery and look forward to the next instalment by this talented author.” —Bloodstained Book Reviews

“I think this character could show up in several more books and I’d be glad to see her.” —Reviewing the EvidenceRelease date: December 12, 2023

Publisher: Open Road Media

Print pages: 280

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Chanukah Guilt

Ilene Schneider

Chapter 1Saturday, November 23

I hate funerals.

No one really likes funerals, except maybe Harold and Maude, and they’re fictional. I guess I should say that no one I know in real, rather than reel, life likes them, but I really, really hate them. That’s because I have a tendency to cry.

I realize that it’s acceptable, even healthy, to cry at funerals, but I overdo it. It doesn’t matter if the funeral is for a friend, an acquaintance, a relative, a stranger, a child dying too soon or an older person who’s lived a full life. As soon as the eulogy starts, I take one look at the bereaved in the front row, and, bingo, the water works begin. I cried so hard during the funeral scene in Steel Magnolias that I was worried I would be asked to leave the movie theater. Even life insurance ads leave me weepy.

Generally, excessive crying at funerals is permissible. But not when the person crying is the officiating rabbi.

Over the twenty-five or so years I’ve been conducting funerals, I’ve trained myself to disconnect or dissociate or compartmentalize my feelings or whatever this year’s pop psychology buzzword is. Usually, I take a deep breath, look somewhere just over the mourners’ heads, and get through the service with barely a catch in my voice.

This funeral, though, wouldn’t present any problems of the lachrymose variety. In fact, it would be hard for me to show any sympathy at all as I tried to find something nice (or not too nasty) to say about William Phillips, self-made millionaire, real estate developer, and land rapist. To complicate matters, I would have to remember that his name was William Phillips, not Phillip Williams. Interchangeable names always confuse me.

I had never met Phillips, but that didn’t stop me from disliking him. Nobody had liked him, not even his several wives, past, current, and future. Not even his kids, from what I had heard. In fact, I would guess that no one, not even his mother, had ever given Phillips unconditional love except for his granddaughter. And she was still a toddler.

Fortunately, the family had decided to have a graveside funeral. Fortunately for me, that is, since there’s no eulogy at a graveside service. I would have to say something—the family wants something for their money—but not the twenty-minute praise-filled speech they expect when the service is held at the funeral home.

Phillips was such a prominent person in the community—not popular, but famous for his infamy—that I was surprised when I came home from services late Saturday morning to find a message from the funeral home asking me to preside at the funeral the next day. Generally, when someone dies on Shabbat—Friday sundown through Saturday sundown—the funeral would be on Monday, or even Tuesday, to allow the family to notify friends and to give non-local relatives time to arrive.

“How come they decided to have a graveside, and so quickly?” I asked Caryn Rozen, the newest member of the Ruben family to join the family funeral home business.

Caryn and I had gone to rabbinical school together for a year before she had gotten married and decided to go into early childhood education instead. We had been good friends and movie-going buddies then and had kept in touch off-and-on through the years. After her recent divorce, she had decided to accept her grandfather’s offer to pay for mortuary college if she joined the family firm. Now that we lived in the same area, we had reconnected. Caryn and I are friends in part because we share the same warped sense of humor, tinged with a streak of cattiness, so her professional sense of honor wasn’t offended when I asked, “Are they

afraid that no one would come?”

“The ‘official’ reason is they want to bury him as soon as possible, ‘in accordance with Jewish tradition,’” she answered. We both laughed, although mine came out as a snort. According to Janet Brauner, one of the few congregants who had shown up for services that morning and my source for everything gossipy, when Phillips had keeled over the previous night, it had been into his lobster special at one of the new upscale seafood restaurants in the area. So much for his devotion to Jewish tradition.

“Remember the scene at the beginning of Charade when the bad guys come to the funeral to check that Audrey Hepburn’s husband is really dead? Phillips’ family didn’t want anyone opening the casket and poking him. Or maybe they’re afraid that everyone will applaud. He left more enemies than friends, and no one’s particularly mourning him.”

She hesitated. “Actually, that’s not true. Madison, the middle child, is upset.” So much for my suspicion that only the two-year-old loved him.

Caryn continued, “And Tyler’s pretty torn up, but I think it’s because Phillips died before he and Jennifer were even formally separated. Chances are that he hadn’t changed his will, so Jennifer will get the bulk of his estate, while Tyler gets nothing. I bet even her condo’s not in her name.”

“Wait a minute.” I said. “Back up. I know Jennifer is the trophy wife, but who is Tyler?”

“Tyler’s the trophy-wife-in-waiting. When you’re as rich as Phillips was, you get to change wives every couple of years, along with your luxury car. I think she’s about twenty—an aerobics instructor, of course. What a stereotype.”

I sighed. “I’m not sure I want to do it. I was planning to go to Brig tomorrow afternoon.” I’m an avid birder, and the Edwin Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, Brigantine Division, about fifty miles from my house and ten miles northwest of Atlantic City, is one of my favorite birding places. “I don’t know him or his family. Why choose me?”

Caryn chuckled, “He left instructions for his funeral, including a list of the rabbis he didn’t want. You’re the only one not on the list, but that’s probably because you’d never met.”

“Thanks for the vote of confidence.”

“Don’t take it personally. He managed to alienate everyone.”

Caryn suddenly switched gears. “Hey, did you know he donated the land for your synagogue?”

“You mean that worthless piece of shit?” Mishkan Or, where I worked, was the

result of a merger of two small, isolated, rural congregations. Our building, which was tiny compared to the mega-complexes in nearby Cherry Hill, had been built about twenty years before on several acres, most of which were under water when it rained. We couldn’t expand the building or the parking lot even if we had the money to do so.

“I bet he gave it to us because he couldn’t develop it. That way he got rid of a tract that was losing him money, and deducted it as a donation.”

“Don’t be such a cynic. Although you’re probably right.” Caryn got back to business. “Listen, the family wants to have the funeral in the early afternoon, but I’ll tell them they have to move it to the morning. Then you can still go birding in the afternoon. And don’t tell me you can’t use some extra cash.” She had me there. Even though I work full-time as Mishkan Or’s rabbi, it’s a small place, with only about one hundred twenty-five members. The pay is about half of what I could earn in a larger place, and two-thirds of what I had been earning thirteen years earlier when I had turned forty and had a mid-life crisis, shedding both my job and spouse in the process. I had traded in my plum position as assistant rabbi/gofer in a large, urban, urbane, and affluent Philadelphia synagogue and moved fifteen miles away to Walford, New Jersey, a former farming community that was now the epitome of suburban sprawl. It was mostly known as the home of Walford University, dubbed Triple-U (as in “Double-u U.”).

The job isn’t prestigious, and it isn’t going to make me rich. I’ll probably be eighty before I save enough to retire. But, for the first time in my life, I’m doing what I want and not what society expects. I’m no longer the hippie alternative educator I was in the Seventies or the made-in-the-male-image religious leader of the Eighties. I can wear comfortable clothes to work. I can hold discussions instead of delivering sermons. I can get to know my congregants on a personal level. I can write and read and make my own hours, within some limits. Even though my entire townhouse could fit into the living room of some of the newer houses in Walford, I’m driving a thirteen-year-old car, and my vacations are mostly visits to family members with sofa beds, I’m more content with my life than I’ve ever been.

But it looked like I wasn’t going to do what I wanted on this Sunday. Caryn was getting desperate. “I’ve got to make this funeral go smoothly,” she begged. “It’s the first time my family is letting me solo, and it’s a biggie.”

I sighed and gave in to the tone of pleading in Caryn’s voice. “I’ve got to be at an adult ed. breakfast tomorrow morning at the synagogue until at least eleven-thirty, so tell the family I can only make it after one.” There went any hopes of going to Brig. tomorrow.

“Done. No problem. I owe you.”

“Don’t worry. I’ll

collect. You’d better fill me in before I call the family. Whom should I talk to? Whom should I avoid mentioning?”

I could picture Caryn in her office—a small, windowless one, in accordance with her position as junior member of the firm, even though she was older than her co-worker brothers. She would be settling back in her chair, kicking off her plain, black pumps, pushing her stylish but understated suit skirt up her legs, and putting her black pantyhose-clad feet on the desk. She was probably running her hands through her short, gray-streaked, brown curls. “Here goes.” I’m sure I heard her cackle. “You’d better take good notes. In this case, you really can’t tell the players without a scorecard.

“Ready? Here are the names: Phillips’ mother, Henrietta—I think it was originally Yetta—is at least eighty-five years old and looks not a day over eighty-four, despite frequent trips to Switzerland for injections of sheep placentas. The ex-wives are Sylvia and Marilyn. Jennifer is his current wife. Rumor has it that she was slated to be replaced by Tyler, but you’d better not mention her in public. His sons with Sylvia are Kenneth, who’s married to Kayla, and Brian, who’s divorced. Their half-sisters, via Marilyn, are Madison and Ashley. Samantha, who’s still an infant, is his daughter with Jennifer. His only grandchild, Ken and Kayla’s daughter, is Sophie. So far as I know, Tyler’s not pregnant.”

I had to laugh again. “Are those really the names, or are we preparing a list for a sociological survey on the changing American taste in children’s names?”

“Yup, the names are real, and wait till you meet them.” She hesitated again. “Um, I forgot to tell you.” Uh, oh, I thought, here it comes. “It’s at Hills of Eternity.”

Terrific, not only had Caryn suckered me into giving up a birding day to do a funeral for a man I had never met and instinctively didn’t like, but she was sending me an hour away to do it.

“Okay,” I grumbled. “I need to restock the freezer anyway.” The cemetery is on the far reaches of the northeast corner of Philadelphia, almost to Bucks County. On my way back, I would stop at one of Northeast Philadelphia’s kosher supermarkets and pick up some chicken. I may like to watch birds, but I also eat them. “Better make it two o’clock instead. And tell the probably very merry widow that I’ll call after Shabbat.”

Caryn tried to make amends. “Let’s get together for lunch soon—my treat—and compare notes. And make sure you go to the shiva—I want a full report on the house. It’s supposed to be spectacular.” We made plans to get together on Monday for lunch at the Mexican Food Factory in Marlton, halfway between Mishkan Or and the Ruben Funeral Home. But it was a lunch that would be postpone postponed, several times.

Chapter 2

I took a quick glance at the clock and realized that I could still get to Brig to go birding today, now that tomorrow was out. Despite my long conversation with Caryn, it was only noon; once again, we hadn’t gotten a minyan, the requisite ten adults for a prayer service, that morning, so I had gotten home earlier than usual from the synagogue. I still had time to change into jeans and a sweatshirt, grab a quick yogurt for lunch, pack a snack, load up the car with my spotting scope, binoculars, and every birding guide in publication, and be on the road by twelve thirty. I could be at Brig by one forty-five and be finished with the eight-mile driving circuit before sundown.

There was only one problem. I hadn’t filled up the gas tank before Shabbat, and there was no way my trusty, rusty Toyota with one hundred forty-five thousand miles on it was going to make the one hundred-plus-mile round trip on less than a quarter tank of gas.

I’m not Orthodox, obviously, or I wouldn’t be a rabbi, but I do keep Shabbat after a fashion. I use electricity, watch TV, cook, drive, but I don’t use any money. Ergo, no gas stations on Shabbat.

Brig is part of the National Wildlife Refuge system and charges admission. To get around the problem, I buy an annual Duck Stamp, which gives me free access to the National Wildlife Refuge system. It also qualifies me to get a hunting license, but I would rather eat birds that someone else has killed.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t help me fill my gas tank.

I put the yogurt back into the fridge and was looking for something more substantial but equally easy to prepare when the phone rang. When I picked it up, I was sorry that I hadn’t taken the chance with the car. I would rather run out of gas in the middle of nowhere than deal with my sister Jean.

Jean and I have always had a troubled relationship, to put it mildly. She’s fifteen years older than I am and was born when our parents were first married and in their early twenties. I showed up unexpectedly when my mother was thirty-nine; she had assumed she was menopausal and hadn’t even gone to the doctor until she was in her sixth month and had gained forty-five pounds.

I was an acute embarrassment to Jean, visible proof that her parents were still “doing it.” Not that she had a clear idea of what “doing it” meant, only that her better-informed friends found the whole idea to be a combination of ludicrous and hysterically funny. Teens in the late Forties had been more naive and ignorant than they would be even ten years later.

It wasn’t until I took my first graduate-level counseling course and had to write a psychosocial history of my family that I realized something else. I wasn’t just proof that our “elderly” parents were sexually active. Worse, people thought that Jean was my real mother and that our parents had pretended I was theirs as a ruse. Jean had been a large, chunky teenager, and she tended to wear baggy, ill-fitting clothes in a misbegotten attempt to hide her weight. Shortly after I was born, she went on a crash diet. She did lose weight—and kept it off until her first child was born—so all of a sudden there was a slender Jean and a new baby in the house. Add to this the fact that I look absolutely nothing like either of our parents or like Jean, so my looks must have come from someone else.

Actually, I’m a throwback to some great-great whatever. I met a second cousin at my father’s funeral fifteen years ago, and we could have been twins.

“Spring, you have to do something about Mother.” Jean never called me by my Hebrew name, Aviva, which I now use exclusively.

I took the portable

phone into the living room and sank into the couch with a sigh of resignation. It was going to be one of those calls.

“What’s Mom done now?”

“It’s not what she’s done; it’s what she hasn’t done. It’s almost winter, and she’s insisting on staying in Boston. I don’t understand why she won’t move to Florida.”

Because you live there. I thought it, but didn’t say it. This time.

“You know she hates Florida and the humidity. She has her friends and her doctors and her activities. Everything she’s familiar with is in Boston.”

“But still, at her age! What if she slips on the ice and breaks a hip?”

“And what if she moves to Florida and gets eaten by an alligator? Listen. We can’t live our lives with ‘what ifs.’ Mom’s healthy enough for a ninety-two-year-old, her mind’s still sharp, she gets around just fine, and it’s not as though she lives alone. The assisted living facility she’s in is fantastic, and Larry and his kids visit her all the time. Just leave her alone and let her be happy.”

I could tell that Jean was about to make some rejoinder about it’s not being her fault if Mom’s not happy, but she thought better of it and changed tack.

“And you’d better talk some sense into Trudy.”

I knew what she was referring to, but played innocent. “What’s Trudy planning to do now?”

“As if you didn’t know!”

I did know. My forty-eight-year-old niece, who was more of a sister than a niece, was thinking about adopting. It would be her second child, actually, since her life partner, Sherry, had been artificially inseminated seven years earlier. But Jean had never accepted that Trudy was a lesbian or that Sherry and their son Josh were anything more than roommates.

“If you’re talking about their adopting a second child, I think it’s terrific. You’re the one who needs some sense talked into her.”

“It’s not terrific. She’s too old. And she’s single.”

I took a deep breath. “First of all, a lot of older women are having children or adopting. Don’t you read the papers? There’s no such thing as ‘too old.’ And, second, she’s not single. She and Sherry have been together for—what is it now?—sixteen or seventeen years? I know they were together before Dad died. Don’t you think it’s time you acknowledged their relationship?”

I was treading where Jean didn’t want to go, so she changed subjects again. “Where are you going for Thanksgiving?”

“To Trudy and Sherry’s.”

“I don’t understand why Trudy won’t come to Florida to visit me for Thanksgiving.”

Probably because the invitation is only for Trudy and doesn’t include Sherry and Josh. But again, I only thought it. “I guess she’s too busy to get away. And it’s expensive to come down for only a few days.” I decided to add a bit of a jab. “Isn’t Larry coming down?” I innocently and insincerely asked.

Unlike Trudy, who, to hear Jean complain, was a failure, despite being an extremely successful and wealthy software developer, Larry, to hear Jean brag, was a combination of Bill Gates and Mother Theresa. There’s no question that he was a good person—the fact that he visited his grandmother willingly and happily was proof of it—and had been contentedly married to the same woman for twenty-two years. Their kids were in college and had never gotten into any kind of trouble. Even though Larry had barely finished his second-rate college, he was moderately successful selling insurance. He and his wife lived in a nice, but not upscale, suburb of Boston. My nephew really was a perfectly nice guy. And perfectly boring.

Jean would hear no criticism of her prince. “He’s busy. He has clients to see. And I’m sure they’ll be here to visit soon. Or maybe I’ll come up to Boston after there’s no more snow. I want to see Mom anyway. And my grandchildren.” I knew she was referring to Larry’s kids, not to Josh, but I let her comment pass unchallenged. I must be weakening in my old age.

After a few more inconsequential complaints from Jean, including one about why she always had to initiate the phone calls, she finally hung up. I now definitely needed something more substantial than yogurt. Something with calories and carbohydrates and sodium. Left over anchovy, onion, and mushroom pizza was just right. Followed by a large bag of microwave popcorn. And maybe the rest of the pint of Ben & Jerry’s, with whipped cream, of course.

I fed the cat, named Cat because no feline of my acquaintance has ever answered to any name that didn’t sound like an electric can opener, and watered my plants. Then I spent the rest of the day lazing around reading the paper. The nice thing about subscribing to the major Philadelphia daily is that parts of the Sunday paper are delivered on Saturday. Since Sunday is usually a busy day for me, I like taking advantage of my Saturday time off to read the paper.

The news section was the same old, same old. US politicians were still engaged in mud-slinging fest rather than problem solving. Pakistan and India were growling at each other, but with nuclear weapons on both sides, any skirmish would not be a minor one. There had been a massacre in a crack house in North Philadelphia. WUMPAH, the Walford University Museum of Pre- and Ancient History, Walford’s main claim-to-fame,

had just discovered that someone had managed to steal a figurine of an ancient Canaanite goddess from its display case. A suspicious fire in Camden had killed two young children. Several parents in Cherry Hill were arrested for serving alcohol to their underage kids. The local Walford Chief of Police was being investigated for taking bribes, Police Department morale was in the toilet, and the Mayor was calling an emergency session of the Township Council to approve the hiring of an outside consultant.

It was with a sense of relief that I turned to the comics; I always read them last as a reward for getting through the rest of the paper.

Chapter 3Saturday, November 23–Sunday, November 24

Sundown, marking the end of Shabbat, comes early this late in November, so I called Jennifer Phillips around six thirty that evening.

“Hello. This is Rabbi Cohen. I believe that Caryn Rozen of Ruben’s Funeral Home told you I’d be calling this evening. I’m sorry for your loss. Is there anything you’d like me to say at the service tomorrow?”

The silence at the other end was so long that I thought we had been cut off. Finally, there was a frosty, “No, I can’t think of anything. Just do the regular things. I think my stepdaughter Madison may want to say a few words. She has this crazy idea that she wants to be a rabbi.”

There was another silence as Jennifer realized her faux pas. Then she went on as though nothing had happened. “We’ll see you at the cemetery.”

I spent the rest of Saturday night trying to decide if I wanted to go to the movies by myself until it was too late to go anyway. So I settled for an evening with Hugh Grant. Actually, it’s not that I like Hugh Grant all that much—well, okay, I do—but both Four Weddings and a Funeral and Notting Hill have terrific supporting casts and witty dialogue, thanks to writer Richard Curtis, who was also responsible for The Vicar of Dibley. I’ve decided that if a reporter ever asks me who my role model for the rabbinate is, I would answer “Geraldine Grainger.” Besides, I’m a sucker for a British accent.

Sunday morning was one of those unseasonably warm, clear, cloudless, brilliantly blue days when you wished you could be anywhere but where you had to be. I certainly wished I didn’t have to be wearing pantyhose and discussing the “December Dilemma” again with the Men’s Club and Sisterhood.

It was a good thing I had a designated parking spot—the sign read, “Reserved for Rabbi. Thou Shalt Not Park”—as the lot was filling up. I went into the office wing. “Morning, Liz,” I yawned at my part-time secretary, Liz Smithers.

“Morning, Rabbi. I see you are your usual chipper self this morning. And you’re wearing your uniform—must have a funeral today, right?”

“Observant as always, Liz,” I grinned. She knew my dislike for “dress-for-success” clothing, or for sober colors, so if I was wearing my one suit—charcoal gray, no less—then I must be going to a place where a long brightly-patterned crinkle cotton skirt with an oversized T-shirt would be inappropriate. The suit was actually two separate pieces that matched enough to pass muster as a “professional” outfit. The skirt had an A-line skirt and elastic waist, and the jacket was more like a cardigan, in a soft unconstructed style with sleeves I could push up, so the cuffs didn’t dangle over my wrists. Under the jacket I wore a forest green, short-sleeved, washable silk T-shirt. If I had to look “rabbinic”—tough considering my gender—at least I was going to be comfortable. In my previous job, I had been required to wear tailored clothes, which I can’t stand doing. Not only do I find them restrictive, but they never fit me right anyway. Even if a straight skirt looks okay when I’m standing, I usually can’t sit in it. The same with jeans: if they don’t have an elastic waist band the whole way around, I can’t breathe when I sit.

Then there’s the problem of being a “petite” height and “women’s” weight. Clothing manufacturers assume that anyone less than five feet four inches is flat-chested, and anyone who wears over a size twelve is at least six feet tall. Is it any wonder I go around looking like a middle-aged boomer in mourning for the Sixties? Which,

come to think of it, I am.

“I’m doing the funeral for William Phillips this afternoon. I know,” I responded to Liz’s raised eyebrows—a retired school librarian, she could say more with her eyebrows than most people can with a microphone—“it goes against my nature to be nice to someone who doesn’t care about the environment, but funerals are for the living. He’s got kids. They’re not responsible for his work.”

Liz nodded briskly and got back to sorting Saturday’s mail. I rifled through it, to her annoyance, as I was disrupting her order. I looked suitably abashed when she glared at me, and asked, “Is Ron here yet?” Ron Finegold was our part-time cantor and part-time school director.

“He’s in the auditorium, making sure everything’s ready for the Chanukah Bazaar today.” This year, Chanukah was very early, the day after Thanksgiving, so we were holding the annual Bazaar—a chance for the kids in the religious school to buy little gifts for their families and friends—before the Thanksgiving vacation.

“Anyone here yet for the breakfast?” I asked.

“Yes, Janet and Phil are setting up the conference room with bagels and spreads and drinks. A few others have wandered by.”

“Okay,” I waved, “I’ll mosey over there. Hold any calls. I’ll check in before I leave for the funeral.”

Phil Brauner was a founder of one of the original synagogues, and had been instrumental in the merger. A former president of Mishkan Or, he was a vigorous seventy-year-old who volunteered for everything, from buying bagels to changing light bulbs to reading Torah when the cantor was on vacation. He was tall and pudgy with the look of a former athlete who had stopped exercising, which is exactly what he was. As soon as he retired from his job as a high school phys. ed. teacher and football coach, he became a confirmed couch potato. His main form of exercise now, he claimed, was surfing—channel surfing, that is. What hair he had left was white, and he was an unassuming, modest, and funny guy who really was the backbone of the synagogue.

Janet, on the other hand, was useful only in that she was a major gossip. Because of her motor mouth, I was very well informed about the private lives of the congregants. Much to her chagrin, though, I refused to confirm or deny any of the information she had gleaned elsewhere. I also made sure that no one had an appointment with me for marriage counseling or other advice if she was going to be in the building. If she saw someone enter my office and close the door, she would pry until she found out what was going on.

But she never found out from me. I had discovered that if I just looked interested,

she would tell me everything she knew, and never realize that she wasn’t getting anything back.

Janet was medium height and so thin as to be gaunt. Her hair was dyed menopausal red, and years of smoking had left her with a raspy voice that made Lauren Bacall sound like Betty Boop. She was also beginning to develop a dowager’s hump, and I always felt like buying her a bottle of calcium tablets. But I had learned to stay out of people’s affairs—if they wanted me to know, they would tell me.

I stuck my head inside the door to the conference room and waved good morning. “Boker tov, Rabbi,” Phil boomed. “Come on in.”

“I’ll be right back,” I said, scanning the room and realizing that most of the people hadn’t come yet. This was going to be a “Jewish time” event—beginning at least fifteen minutes after scheduled. I also noticed that Phil and Janet had gotten up early enough to buy freshly baked bagels. The previous month, Phil and Janet had been away, and we had to make do with defrosted and freezer-burned bagels. “I want to check the auditorium and make sure that Cantor Finegold doesn’t need anything.”

The auditorium was bustling with parents setting out the inexpensive trinkets they thought the kids would like to buy. The smell of frying latkes was wafting from our inadequate kitchen, and boxes of jelly donuts were being emptied onto paper plates. “Boker tov, Ron. Everything seems to be under control.”

“Hey, Rabbi. Yup, we’re just about ready. The teachers will be bringing the kids in around ten. Then it will be chaos.” He gave the goofy grin that endeared him to so many of the divorcees in the synagogue, and ran his hand through his sandy-colored longish hair. It’s a good thing that Ron was oblivious to the effects of his charms, or, I suspect, his wife would have found it necessary to perform a “Bobbit” on him.

We were lucky that we had been able to hire Ron. Not too many people were willing to work for the paltry salary we could afford, but with my lack of a singing voice, a cantor was a necessary expense. We had combined the job with that of the school principal so that the salary wasn’t a complete insult, but it still wasn’t enough to live on, especially in a suburb. Ron was a stay-at-home father, though, and Brenda Fishman, his wife, a literature professor, had tenure at Triple-U. The hours fit his schedule, we didn’t mind if he brought his kids to the office, and the extra income gave them that financial boost they needed to make it feasible for them to stay. Not that they were planning to leave—tenured positions, especially in the liberal arts, were few and far between.

“I’ll stop by after the adult ed. breakfast, but I won’t be able to stay long. I’ve got a

funeral in the Far Northeast at two.”

“Yeah, I noticed the clothes.” I was becoming entirely too predictable. “See ya later.”

I walked back to the conference room, stopping to poke my head into the classrooms and greet the children and teachers. By the time I got there, the room had filled up with the usual cast of characters.

Because Chanukah would be over well before Christmas, the comparisons between the two winter holidays would be fewer in the public’s—and the advertisers’—minds this year. I was bored with the topic of the “December Dilemma,” but it seemed to be a perennial favorite, even when I spoke to a church group or as a guest in a comparative religions class at Triple-U.

My technique is to throw out a question or a provocative statement and sit back and let the debate begin. Generally, the discussions are lively and surprisingly civil.

“In 1870, Congress passed an act recognizing Christmas as a Federal holiday, at least within the District of Columbia. Then, in 1894, Congress began issuing a list of public holidays that included Christmas. If we, as Jews, have no difficulty celebrating other civic holiday, like Columbus Day and the 4th of July—”

“Thanksgiving!” Carole Brookner interrupted. She was such an enthusiastic, albeit know-it-all, participant in the adult education programs that she had been voted chair of the adult ed. committee.

“Right. Thanksgiving. Thanks, Carole.” I pretended that I hadn’t remembered the holiday we were about to celebrate in four days. “If, as I was saying, we participate in all of these, why do we ignore Christmas?”

“Because it’s in honor of the birth of someone we don’t recognize as a messiah,” the congregation president, Meryl Felsner answered.

“Yeah, Meryl, but what about reindeer and snowmen and Santa Claus and trees? Even the White House has a Christmas tree. The Supreme Court has called those secular symbols. Why don’t we put up a tree with blue and white lights in front of the synagogue?” Carole was off and running.

Meryl shook her head. “But those are all connected with Christmas. Sure, Christians think they’re secular symbols, but we don’t. I mean, it’s not a ‘New Year’s Tree,’ is it? And Santa Claus is named for a saint.”

“We should make sure menorahs are displayed in public, too,” Janet interjected.

“No way,” her husband

rejoined. He was one of the few people who would dare to challenge her. “Dreidels, maybe. They’re secular symbols like trees. But a menorah is a religious symbol, like a crèche, and it’s a ritual object, too.”

I munched contentedly on an everything bagel, making a mental note to pick up some breath freshener before I faced the family at the cemetery, while the debate continued to rage between those who insisted there was nothing wrong with decorating their houses with blue and white lights and those who felt that imitation was not the sincerest form of flattery when it came to holiday decor. I was actually enjoying myself, and it was with reluctance that I realized I had to leave for the funeral.

As promised, I stopped by the auditorium on my way out. The Chanukah Bazaar was winding down, and a lot of the parents had arrived to pick up the car pools. My niece, Trudy, was there to get her son Josh.

“Hi, Josh.”

He looked at the floor and waved.

“What, no kiss for your Aunt Aviva?”

“I hate kisses. Hugs.”

I gave him a hug, which he reluctantly accepted. “How’s it going?” I asked Trudy.

She shrugged. “It’s going. Nothing new. You have a funeral or something?” No question about it, I had to do something about my wardrobe.

I sighed. “Yeah. I’m just leaving now.”

“Anyone I know?”

“William Phillips.”

“Oh, we live in one of his houses. It cost us a fortune to fix the shoddy work he’d done, and we had to put in a complicated sump pump system to keep the basement dry. He’d built on wetlands. I wonder who he paid off to get the permits and occupancy approval.”

Trudy and Sherry lived in a fantastic, semi-custom, contemporary on two wooded acres in Medford. I was surprised to hear that they had trouble with the house. In truth, except for bumping into them when they were picking up Josh from Religious School, or seeing them once a month or so when they went to services, I didn’t get together with them as often as I would like. Or as often as my sister, who would love to sue me for alienation of affections, assumed I did.

I took a look at my watch. “I’ve got to run. See you Thursday. Noonish, right?”

“Right, if you want to help set up before the hordes descend. See you then.”

I got to the cemetery about half-an-hour early. I like to arrive at least fifteen minutes before a graveside funeral, but I had forgotten that there wouldn’t be much traffic going over the Betsy Ross Bridge from Jersey to Philadelphia or on I-95 on a Sunday. Cemeteries,

often the only spots of green in an urban landscape, are largely overlooked Meccas for birders, so I spent the time before the family arrived watching some Crows harass a Red-tailed Hawk.

As the limos from the funeral home pulled up behind the hearse and the family got out, I tried to match faces with names. The hunched over elderly woman with the dowager’s hump and unnaturally smooth face must be Henrietta. If she had another face lift, her eyes would pop out of her head. The two ex-wives looked to be about fifteen years apart in age; I pegged Sylvia as late fifties and Marilyn as early forties. They looked remarkably alike and rather nondescript, of medium height and medium weight, with nicely cut short, wavy medium brown hair with carefully applied blonde streaks (for Sylvia) and highlights (for Marilyn).

The current wife, Jennifer, was close to thirty, but dressed as though she were a teenager, in a tight black leather miniskirt, long tunic-type sweater, and the kind of high heels seen only on Sex and the City. She was so thin as to look anorexic, and her long, straight blonde hair was a shade never seen in nature.

The sons were in their late twenties or early thirties, not handsome but presentable, with the kind of bland, white-bread look I’ve never cared for. They were both tall and thin. Brian, the younger one, was balding and, to his credit, not trying to hide it, while Ken’s hair looked like it had been permed to give it more volume. Ken was also dressed in an obviously expensive and probably custom-tailored designer suit, while Brian was in wrinkled chinos and a blazer.

Ashley and Madison, the two daughters, were as unlike as Jean and me. Ashley looked to be about seventeen, and was still in the sullen “Why me?” stage. She was wearing leggings and an oversized T-shirt, chunky Doc Marten shoes, and spiked hair. Her mother, Marilyn, glared at her the whole time.

Madison, the one who had some crazy idea about becoming a rabbi, was a few years older than her sister. She looked a lot like her mother; in other words, you probably wouldn’t remember her if you met again. The only difference is that she didn’t have any highlights in her hair. She was appropriately dressed in a conservatively cut brown suit.

And then there was Tyler, petite, fit, with arm and leg muscles that probably weighed more than the rest of her body. She wore her hair in a short pixie-ish fringe cut, not quite punk, but almost. I suspect she gelled it into spikes and colored it purple before clubbing. She was wearing a plain black pants suit, with a low cut tank top under the jacket, and dabbing at her artfully made-up eyes with a black-edged white linen handkerchief. I didn’t know they even made those any more.

Even though her status was somewhere between home-wrecker and fiancée, Tyler had arranged to be present with the rest of the family.

Jennifer, even as the trophy wife who was about to be supplanted by a newer-version trophy wife, could afford (literally) to be gracious toward Tyler.

As I walked toward the family to introduce myself, Caryn asked everyone to stand in a line next to the hearse and began affixing the mourning buttons to the family’s clothing.

Henrietta, whose purple silk dress and matching overcoat had probably cost the same as my salary for a month before taxes, said, “I’m so pleased that it’s no longer de rigueur for mourners to wear black. The color makes my skin too sallow. This color is so much more flattering, don’t you agree, dear?” She was trying to sound cosmopolitan, but her voice still retained a hint of the Eastern European shtetl Yiddish that was her native tongue.

She continued. “Isn’t there some other way to attach that, dear? I don’t want the silk to tear.”

“I’ll be careful, Mrs. Phillips. We’ve used these buttons on many silk outfits and never had a problem.” Caryn gave her professional smile, meant to be competent and soothing at the same time.

“Yeah, be careful there,” Ken echoed his grandmother as Caryn approached him, button in hand. “You’ll leave a hole in the lapel. This is Gucci, you know.” I doubted that Caryn could tell the difference between Gucci and Goodwill, but she merely nodded.

“Hey, you’re the traditionalist in the family. Why don’t you tear your lapel instead?” Brian sneered. There didn’t seem to be much love lost there.

When Caryn got to the widow, Jennifer asked, “Do the buttons came in different colors? I want to coordinate them with my outfits during the shiva.” She didn’t bother adding that they planned to sit shiva, the seven days of mourning that begin right after the funeral, for only three days.

“Sorry,” Caryn explained. “They only come in basic black.”

“Oh, well,” she sighed. “At least black goes with everything.”

That’s why they call it “basic,” idiot. In a rare show of diplomacy, I didn’t say what I was thinking. I really wasn’t getting the warm fuzzies for this family.

Madison seemed to be the only one really affected by her father’s death. Her eyes were red-rimmed, and there were bags under them, indicating that she hadn’t slept much.

I waited until Caryn was finished with the buttons and then introduced myself. I led the family in reciting the blessing said by mourners when they tear the cloth hanging from the button, and then took Madison aside. “I understand from your stepmother than you’d like to say a few words about your father?”

She nodded, swallowed, cleared her throat and looked at the ground.

“Yes, if it’s okay.” She was going to have to become a lot more assertive and confident if she were ever going to make it as a rabbi.

I told her it would be very appropriate and fitting for her to speak about her father, and then checked to see if everyone had arrived. The obituary in the paper had said that the services would be private, but that people could pay their condolences later at the house. The only one who wasn’t there was Kayla, Phillips’ daughter-in-law. I asked Jennifer if she were expected.

“She decided to stay at our house with her daughter and mine—they’re too young to be here. Of course,” Jennifer continued, “the nanny is there, too, to help the housekeeper set up for the shiva meal. And it made so much sense to have a lot of activity in the house. After all, the children are too young to be here, and someone needs to be at the house to protect it from burglars. You do know, don’t you,” here she leaned in to talk to me confidentially, as though she were about to impart some deep, dark secret, “that robbers read the obituaries and break into houses while the families are at the funeral?”

Actually, I had always heard that story, too, but I didn’t know anyone it had happened to. And I didn’t bother correcting her as to the proper uses of “burglar” and “robber.” Instead, I gave a slight nod of acknowledgment, and suggested that the family members gather together around the grave site, so we could begin the service.

When I nodded to her, Madison stepped to the front and talked about her father. “I know that we probably describe a dysfunctional family,” she began, to everyone’s discomfort, “but Dad made us function. He made sure that we all got together as one family. Once when I was mad at Jennifer for something, Dad said I didn’t have to love her or even like her, but I did have to respect her. And that’s all he wanted—respectability.”

She looked at the mahogany casket and choked out, “I love you, Dad. I miss you. And I respect you.”

Her simple and brief comments were moving, probably because they were heartfelt.

As the family began to get back into the limos, I stopped Madison. “Your comments were very beautiful.”

She obviously wasn’t used to compliments, because she actually blushed. “Thank you.” She looked around furtively. “May I come speak to you in your office? In private? I need to talk to someone. I killed my father.” The last was whispered, and I wasn’t sure I heard her correctly.

“Of course, you can come talk to me any time. But don’t feel guilty. I’m sure there’s nothing you could have done to save your father.”

“No, you don’t understand. It was my fault.” She looked around again, but no one was paying attention to us. “I’ll explain when I see you. Is tomorrow okay? Around eleven?”

Monday was my usual day off, but since I was taking off Thursday for Thanksgiving, I was planning to go to the office anyway. I would have to call Caryn and postpone our lunch, but this was too intriguing not to pursue. And Madison was obviously suffering. “That will be fine. I’ll see you then.”

As she walked away, the almost-teary (real tears would have smeared her make-up and real expressions of grief would have encouraged premature wrinkles) almost-fiancée stopped me from going to my car and said, not all that softly, “Why aren’t the police investigating Billy’s death?”—Billy!? I couldn’t imagine anyone calling William Phillips anything but William—“Isn’t it obvious that Jennifer killed him before he could divorce her? Don’t you know anyone who can help?”

Great. Here this guy had died of natural causes and there were two “suspects” in his death.

I have no idea why Tyler thought I knew someone on the police force. Even in a small town like Walford, I had only met the Chief a few times at community functions and at meetings to discuss post-9/11 security arrangements for public and religious buildings. Whenever I needed to arrange traffic control for the High Holy Days, I spoke to one of his subordinates.

I tried to be gentle as I reminded her that there were no signs of foul play in William Phillips’ death. “I know you’re upset, Tyler, but he died of a heart attack. Jennifer had nothing to do with his death.” Unless, I appended silently, his wife had been spiking his low-fat foods with saturated fats. For that matter, it was more likely that Tyler herself had contributed to her almost-fiancée’s death. After all, it couldn’t have been all that easy for a sixty-one-year-old sedentary businessman to keep up with a twenty-year-old aerobics instructor.

I excused myself and took a quick look at my notes. Whew—it was Tyler. For a moment, I had been afraid that her name was Taylor. It’s not only interchangeable first and last names that give me trouble. I have an awful memory for names, period. It’s a definite handicap (sorry, challenge) in a profession that deals with people. I hate it when someone coyly comes up to me, usually at a wedding or bar mitzvah, and demands, “Remember me?” Chances are, it’s a former student whom I haven’t seen in twenty years. To compound matters, there’s a definite difference in appearance between a sixteen-year-old and a thirty-six-year-old.

Even worse is when I had just met the person a few weeks—or moments—before, and still couldn’t remember the name.

The limos left and I was free to go grocery shopping and collapse when I got home. Except I couldn’t collapse, because there was a ton of laundry to do. One of the nice things about living alone is that

I don’t have to worry about anyone’s laundry but my own. On the downside, there’s no one else to worry about my laundry either.

I hadn’t been asked to help out with the shiva, and even though Caryn would be disappointed that I hadn’t seen the inside of the Phillips’ McMansion, I wasn’t about to volunteer. Little did I know I would have reason to be there the following week in an “undercover” role. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...