- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

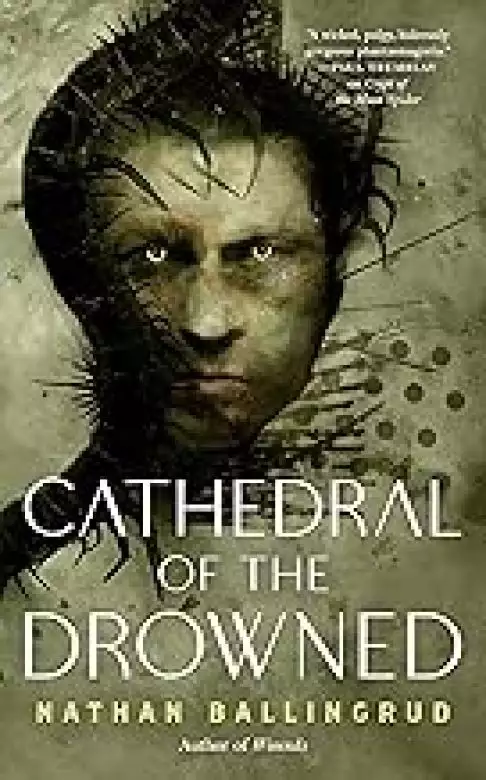

The sequel to Crypt of the Moon Spider, Cathedral of the Drowned is a dripping, squirming, scuttling tale of altered bodies and minds.

There are two halves of Charlie Duchamp. One is a brain in a jar, stranded on Jupiter’s jungle moon, Io, who just wants to go home. The other is hanging on the wall of Barrowfield Home on Earth’s own moon, host to the eggs of the Moon Spider and filled with a murderous rage.

On Io, deep in the flooded remains of a crashed cathedral ship, lives a giant centipede called The Bishop, who has taken control of the drowned astronauts inside. Both Charlies converge here, stalking each other in the haunted ruins, while a new Moon Spider prepares to hatch.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: August 26, 2025

Publisher: Tor Publishing Group

Print pages: 96

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cathedral of the Drowned

Nathan Ballingrud

I.Ghosts of Red Hook

Two ghosts visited Goodnight Maggie in the summer of 1924.

The second arrived on the same night they dragged Handsome Billy from the harbor, his belly slit from cock to collarbone and his innards spilling out like wet fish. She came home to a revenant from her past, the man in the moon she’d thought a year dead. He crouched by the steps to her brownstone, hidden so well in the shadows that she would have missed him entirely had he not stood to present himself as her driver pulled away.

It was four in the morning. Clouds scudded across the sky. Rain had threatened all day, but there had been nothing but a cold, driving wind. She’d just come back from the docks, where Billy’s corpse had been discovered in a fishing net dropped in front of McElhone’s Fishery, the warehouse from which she ran a gang that, until a few months ago, had run the docks in Red Hook with uncontested dominance. They handled booze, gambling, and prostitutes, but what kept them in control was their exclusive access to moonsilk—spiderwebs smuggled from the forests of the moon, which bestowed incredible dreams on those who ingested it.

Then the Sicilians started arriving, and with them came a new organization calling itself the Mafia. They were brutally strong, and they wanted what she had. The death of Handsome Billy—seventeen years old, a sweet child with a useful mean streak—made that clear.

So when a youngish, disheveled man, who years ago had been one of her most ardent customers, lurched unexpectedly from the shadows in front of her house, she nearly put a bullet through his head from simple reflex. If she hadn’t been numb with cold and so tired that her eyes burned, he wouldn’t have had time to speak.

“Maggie,” he said. “It’s me.”

She recognized the voice, even after all this time. “Come out where I can see you.” The gun did not leave her hand.

The figure shuffled closer, until the lamp across the street illuminated the face of Doctor Barrington Cull.

It no longer looked much like a face at all. The skin had been flayed or torn on the left side from the corner of his mouth to the crown of his head, leaving a pale, shiny mass of scar tissue which pulled his features askew. A hole gaped where his eye had been. He favored his left leg, which looked twisted under his threadbare pants. His clothes were rags: not torn and bloody, but grimy and ill-fitting. A vagrant’s garb.

“I need help,” he said.

Maggie slipped the gun back into her pocket. “I heard you were dead.”

“Yes. I know.”

“Did Charlie do this to you?”

Dr. Cull glanced furtively up and down the empty street, where the streetlamps shed cones of light. The shadows between them festered with possibilities. The neighbors’ windows were all dark at this hour, but dawn was near; they wouldn’t be for much longer. He peered into the cloudy sky, as if frightened something would come swooping down for him. “Please, can we go inside? They’re looking for me.”

“Who are?”

“The Alabaster Scholars. She sent them.”

Maggie didn’t know what that meant but it hardly mattered. She didn’t want to be outside any longer, either. “Can you walk on that leg?”

“These injuries are old. I’m fine.”

“Then come on.” She mounted the steps, unlocked the door, and ushered him inside. She hadn’t realized how tense she’d been feeling until securing the locks again behind her. For the moment, she felt safe.

Goodnight Maggie lived alone. Though she had climbed a long way from being the poor little girl from the slums, she’d never been able to shake off the oppressive stink of failure, which lingered despite every hard-won block, every conquered rival, every new stratum of wealth. Her home was warm, her furniture was expensive, and art decorated her walls; still, she spent each night steeped in the shame of poverty.

Dr. Cull followed her into the living room and stood uncertainly while she turned on a lamp and poured two glasses of Scotch whisky. She handed him one and pointed to a leather club chair. “Sit down, Barry.”

A flicker of anger crossed his face. He hated when she called him that. But he said nothing as he took his seat. It struck her how different he seemed now. Seven years ago he’d been a brash young man—probably a genius, though she knew she was no judge of those things. But he’d been conducting experiments on the brains of the mad and the desperate in dingy little shacks along the wharf, using silk he bought from her, and after some trial and error the results became impressive enough that he was able to secure the funding for the Barrowfield Home for Treatment of the Melancholy, located offworld, in the forests of the moon, where the silk was most abundant.

That young man would have corrected her: “Barrington, if you please. Or simply, ‘Doctor.’”

Not disrespectfully. Never that. Cull had always fancied himself a cultivated man; more importantly, he needed her. He needed access to the silk, which she bought from two moonrunners, Little Frankie Delaware and his cousin Cy. They had a tiny rattle-trap ship which would take them to the moon and back, and they had the guts to venture into the forest to harvest the silk. The Moon Spiders were all supposed to be dead; nevertheless, people who went into the woods had a tendency not to come out again.

Maggie sat on her couch and leaned back, not troubling to take off her coat. She closed her eyes, thoughts running amok.

The Sicilians had drawn first blood. She might have given them the booze and everything else, in the interests of survival—but not the silk. That was hers. It had taken too long to find and cultivate her moonrunners, and it cost too much to pay off the right people. She understood that her monopoly on the silk couldn’t last forever, especially as it gained in popularity. But she would not have it taken from her. Not yet, and certainly not by these people.

And Handsome Billy dead. Unforgivable. An outrage that would have to be answered. Billy was a good boy who grew up without a mama and would do whatever Maggie told him to, as long as she treated him with a little kindness. No one is so easily steered as an unloved boy.

Thinking of Billy, as always, recalled Charlie Duchamp to her mind. Charlie was a man in his mid-forties when last she saw him in the flesh; nevertheless she still considered him one of her boys. One of her favorites. Yet he was unpredictably violent, and being unpredictable was a flaw. So she’d sent him to Cull to be fixed. And he never came back home.

Cull would have to answer for that.

She opened her eyes. Cull sat quietly in the chair, as docile as a choirboy. He took a greedy sip from his glass, then met her eyes.

“Thank me,” she said.

“Thank you, Maggie.”

“You made the papers here, almost a year ago. Your precious asylum taken over by the inmates. You and all your staff killed. Barrowfield out of business. The moon an expensive disaster, all travel there forbidden now.”

He nodded, then seemed to change his mind and shook his head. “That’s not the real story.”

“You’ve made things difficult for my moonrunners. Difficult for me. And just tonight the Sicilians killed one of my boys. There’s going to be a war, and it’s a war I don’t think I can win. Now, on top of that, I have to deal with you, too.”

“Not for long. I just have to find a way to get offworld.”

“And go where?”

“Out there. As far as I can.”

Maggie rubbed at her eyes. Thinking was difficult. She needed sleep. “Tell me about these students hunting you.”

“Scholars, not students,” Cull said, a hint of impatience creeping into his voice. “The Alabaster Scholars. They worship the Moon Spiders. She’s using them as assassins now.”

Maggie didn’t know who “she” was but would worry about that later. “They have their own spacecraft? They can find you here?”

“They don’t need vessels. They can travel behind space now.”

He was speaking nonsense. Maybe he was crazy. If so she could dispose of him easily enough. The Sicilians were her primary concern. If they found Frankie and his cousin they would take the silk trade from her. Now Barrington Cull created one more weak spot for her organization, one more point of entry for the Mafia.

She could not let him leave her apartment.

She put on her most reassuring voice and assumed what she thought of as the “mother mask.” “I’ll protect you, Barry.”

He ducked his head. Tears of relief glistened in the low light. “I have to get back up there. I have to go out to the edge of the solar system. I have to see what’s there. Will you help me do that, too?”

“Of course. We have a lot to talk about. But right now we need to sleep. Take the guest bedroom. In the morning, I’ll have my boys bring you some fresh clothes. We’ll figure out what to do, okay?”

“Yes. All right.” He drained the last of his whisky. “It’s been so long since I tasted anything like this.”

“Have another if you like. It’ll help you sleep.”

He stood, a little shakily. “I won’t need any help. I’ve been running from them. I haven’t slept in two days.” Halfway down the hall, he paused and turned back to her. “Thank you, Maggie. I knew I could count on you. You’re the only one on Earth I can.”

She smiled. “Go to sleep, Barry. Everything will be okay.”

Maggie poured herself another glass and sat there for a while longer. She was tired but her mind was spinning like an engine. Barrowfield fell apart a year ago. How long had Cull been back on Earth? What had he been doing? She was furious at this distraction but at the same time felt sure that there was an opportunity here, something she could use in her war against the Mafia. She just had to get him to tell her everything, then study the problem. There had never been a problem she couldn’t think her way out of, never been an adversary she couldn’t outwit.

She turned off the light and made her way down to her bedroom. She put her ear against the closed door of the guest room, until she could make out the slow, regular breathing of Cull, now fast asleep. Quietly she entered her own room and closed the door.

She undressed in the darkness, a soft city light coming in through the curtains. If the windows were open she’d be able to smell the salt in the air from the harbor, the perfume of oil and diesel from the dockyards. Slipping on her nightgown, she sat on the foot of her bed and faced the closet door, which was open only an inch or two.

She desperately needed sleep, but more than that she needed to feel him.

“Charlie? Are you there?”

She hated how much she needed to feel him.

Charlie had been the first ghost to visit her that summer. He’d shown up barely a month ago. Unlike Cull, he was a real ghost, or at least as close to one as she had ever seen.

Her world hadn’t been under siege yet. Handsome Billy was still alive, the Sicilians no more than a storm cloud on the horizon—something to keep an eye on, little more than that. She’d been dressing for bed, just as she was now, when she’d heard the sound: a low static covering a nearly sub-audible hum, like an electric whisper draped over a deep bass current. The hairs on her arms had stood up. And then a pale glow bled from inside her closet, rippling like the reflection of light from water.

A metal orb sprouting dozens of long silver spines in every direction, some of them ending in red or blue blinking lights, rested on the floor. A satellite. It was small—no more than two feet in diameter. Oily water trickled from it in a series of steady streams, as if it rested beneath a small waterfall she could not see.

It was Charlie. She knew it by some peculiar magic, some primordial intuition. She felt it in her brain, on her skin. Later she would understand that it was the moonsilk which enabled this recognition, and which enabled his voice to fill her mind when he spoke—an intimacy she had never believed possible and for which she was not prepared. But in the moment it seemed a visitation from beyond the grave, obeying a logic unfathomable to her.

She could sense him trying to speak. No words came but she felt him reaching for her, touching her, filling the space behind her eyes, between her organs, all the dark places of her body.

“Charlie? Is that you? How can that be you?”

The ghost, if it was a ghost, stuttered and went briefly out; she thought for a moment he was gone, and she felt a sharp panic. But then he flickered back, the strange trickle of murky water still running over the satellite’s shell but disappearing before it touched her floor.

“Where are you? You were supposed to come back to me,” she said. “Tell me what happened.”

He could not. But she felt his yearning, felt his fear and his confusion, and felt, too, the consolation he experienced in finding her, even in this bewildering fashion. She fell back on the bed, frightened and confused herself, as much by the warmth that filled her body as by the weird presence. When he disappeared—abruptly, like an interrupted current—the sudden chill made her cry out. He did not return that night, and although she never partook of the moonsilk she sold, she wondered if her constant proximity to it had finally affected her dreams. But she opened the closet door each night thereafter, just in case. He came back on the fourth night and intermittent nights following. They never spoke, but she almost didn’t mind. She could feel him trying to cross the distance between them. She could feel him in all kinds of ways.

So when Barrington Cull showed up a few weeks later, she was not as surprised as she might have been. She offered him help not because she cared for him or his fate, but because he might tell her what happened to Charlie. She might learn how to bring him home.

And now, preparing for bed with Cull sleeping only a few feet away and the Mafia declaring war, she wanted to feel him again. She wanted to feel something good again. She pulled the door ajar.

“Charlie?”

Silence.

“Charlie.”

After a moment the watery light shivered across the floor, and she felt a gust of warm, thick air. The satellite was there again, lights winking in the darkness.

“There’s my sweet boy,” she said. As had become her habit, she lay down on the floor beside him, closing her eyes, cutting off everything except the feeling of him. She had been ashamed of this at first, as if she were performing an indecent act in public. But that shame had abated quickly enough.

This time, something was different. Riding like a cold current under the warmth of his presence was a stronger fear than she had ever felt from him before. Did he know Cull was in the apartment with her? Or was it caused by something where he was?

“Don’t be scared. You were never scared of anything.”

The fear did not abate. The satellite flickered. A cascade of lights flowed across the tips of the antennae, as if sensors were searching for feedback.

“I’m sorry I sent you away. It was a mistake. I need you here.”

She wiped at her eyes. She had to sleep so badly, but not yet; not yet.

“I wish I could see where you are.”

Instead, she looked through the window at the moon, the last place she’d known him to be, glaring in the sky.

A gibbous white shard.

A pitiless light.

II.Io, Jungle Moon of Jupiter

Long before he found his way back to Maggie, Charlie was born in a jar on the moon. Or so it seemed to him. He came to consciousness staring through clear curved glass into the peering eye of Dr. Cull, who was speaking softly to him the way a father might, gently and with encouragement. Behind Cull, he saw what he knew to be his own body, his head opened like a walnut and a bloody, thready ooze spilling onto the table and dripping onto the floor. An Alabaster Scholar—Soma, the good one—worked over this mess with tweezers and a jar of tiny spiders, which he sprinkled like pepper into the gore. This was Dr. Cull’s specialty: using moonsilk to reconstruct the brains of his patients, after removing the portions he deemed defective. And now, after long service, Charlie himself was the patient. Was the part of the brain in his body on the table the defective part? Or was it this part, himself, contained in this jar? Both were being rebuilt by the spiders and the moonsilk.

Charlie felt a mysterious, profound absence, though of what he did not know. He knew it must be in his other half, and he yearned for it.

“You will travel,” Cull was saying. A spider crawled on the inside of the glass, a mere centimeter from Charlie’s eyes.

I have no eyes.

Was that what was missing?

I have no face.

No body.

Yes, but there was something more. Something even more fundamental than a body.

The body on the operating slab moved with a sluggish lethargy, until Soma twisted a bit of gristle in the exposed brain and returned it to sleep.

What am I?

Charlie felt a wave of bereavement for the ugly hulking thing on the table.

The jar he had become, filled with spiders the same way his body’s head was filled with spiders, was carried away and placed into a narrow, padded receptacle in a large silver satellite, bristling with antennae.

“I’m sending you out, Charlie. This part of you is no good to me here. I need the killer here. But this soft, curious, gentle part, this part of you can still work for me. I know there’s something else out there, Charlie. The moonsilk holds the memories of something ancient and dead. But what? A titan of the stars? An extinct population? Can it be found on other moons, other planets? Are there other beings out there like it, still alive? Go out there and find out for me. What you see, what you hear, all of it will be recorded and sent back to me here. Together we will discover the truth.”

Dr. Cull closed the hatch and for a bewildering moment Charlie was in the deepest darkness he had ever known, a silent abyss empty of all sensation. He had no limbs to struggle with, no eyes to stare with, no mouth to scream with. Madness circled him like a wasp, bitter and aggressive.

And then, like a beam of light, a cascade of impressions saved him. Sight and sound erupted back to life, though not as he’d known them before. Instead, they came to him as information: he understood his surroundings, knew that the smell of overtaxed circuitry and of the doctor’s various alembics were heavy in the air even if he couldn’t smell them the way he used to, was aware of the doctor leaning over his body—the satellite—making adjustments here and there, even if he couldn’t see him the way he understood sight.

“Can you still hear me?” Dr. Cull said. “The satellite’s antennae should be translating sensory information to you now. It’s possible you were able to pick up metapsychic data from your own brain, but that it is a temporary effect which would fade within the hour. This will be much more reliable. And you’ll have a record for me, which is most important.”

Charlie tried to answer, but of course he couldn’t. Yet somehow Dr. Cull had heard him.

“Good, that’s good. Everything seems to be in order. Hang on…”

Charlie understood that Dr. Cull moved over to a bank of machinery and watched a series of words as they were typed across a scrolling sheaf of paper.

“Wonderful. Everything is coming through clearly. Don’t worry, you’ll soon get used to it. You’ll have a long time to adjust. You have quite a journey ahead of you.”

A few hours later, Cull launched him from the roof of Barrowfield Home onto his dark voyage. Before he did, Charlie saw that the other half of him, the half that still lived in his body, had come to observe. A hideous anger radiated from that half. He felt the animosity prickle against his brain like the first tendrils of an electric current. The other Charlie meant him harm. The other Charlie hated him.

Why?

Fear gathered at the base of his thoughts like pooling blood, but before anything happened, he was jettisoned into the dark sky.

The moon and its web-shrouded forests receded behind him, and the dark gulf swallowed him whole.

* * *

Charlie traveled along the currents of ether through an unending night. Without the markers of habit and responsibility, sleeping and waking, time ceased to have any meaning. His mind galloped without restraint. His memories of the moon and what had come before was a pleasant dream pocked by empty craters where things seemed to be missing. He recalled a simple but sweet childhood in Brooklyn and a smiling infant sister, though strangely little of his parents. He recalled being taken in by a gang of criminals as a child, a gang which had felt more like family as the years passed. They taught him to steal from those who had more and would not share. They taught him loyalty and they gave him shelter and a purpose.

He remembered Goodnight Maggie—the one he liked the best, the one who protected him and took care of him. He’d had feelings surrounding her which he couldn’t express. The language of gentleness was obscure to him. She’d been the one to send him to the moon, though he couldn’t remember why.

And there was Dr. Cull. Charlie hadn’t liked Cull. Cull was a small, smug man, quick to bark an order and slow to offer praise. He tried to take on the role Maggie once had, that of protector and guide, but he filled it poorly.

Cull put him in the satellite and sent him away.

How long did he ride the currents between the planets? Nothing to see but distant lights, the occasional vessel whispering silently outward, the tumbling asteroid hulks. Dream and wakefulness became the same strange country, so that sometimes it seemed to him that he saw his own twin staring back at him, affixed to a wall with copious webbing, the top of his skull hanging open as though hinged, his brain pulsing in a low and flickering light.

Sometimes, too, he felt another presence, her presence, the Moon Spider, who was young and growing strong, learning the ways of the web. There hadn’t been a Moon Spider when he was sent away, but he felt her there now. He didn’t understand it and shied away from these strange impressions.

As time passed, other, stranger memories swam to the surface.

Dr. Cull said it came from the “ancient and dead” thing stitched into his mind. Maybe, but the memories were very much alive. Charlie thought of it, at first, as the Other: the separate thing inside him, filling in the places where he had been scooped away. But as the journey progressed he began to lose the ability to distinguish them from his own, the Other from himself. It seemed to him eventually that it was Charlie who strode the starry avenues, who visited fantastical cities no human eye had seen or could even perceive, who slept and dreamed on the soft skin of living worlds.

Who am I now?

Eventually, one of the stars grew from a white granule to a sky-filling leviathan, striated with storms and spangled with moons, and he knew this must be Jupiter. Who knew there could be so many moons? Charlie could not look away from its terrible beauty. He grew steadily closer to one of them, a green moon pocked with glaring red lights.

The moon claimed him.

The satellite plummeted through boiling storm clouds and burned a bright streak through a sky lashed by lightning and dense with volcanic ash. The landscape beneath was lit by dozens of active volcanoes, the light of spilling magma illuminating a world draped in perpetual night. Miles of jungle hugged the coastline of a lashing sea, and it was into the shallows of that sea that the satellite finally crashed.

Sea water washed over him, overwhelmed him, and then receded again, leaving him briefly exposed in the sand. A raucous jungle obscured the horizon to one side; behind its canopy of peculiar trees rose a volcano, jagged black rock spilling a slow radiant lava, showers of sparks spitting into the cloud-dark sky.

On the other side, toward the sea, what appeared to be a massive Gothic cathedral was half submerged in the water, tilted at a slight angle so that its steeple pointed ten degrees to seaward. Intricately carved exterior walls were painted with seaweed, barnacles, and odd, scuttling life. Huge booster rockets built into the sides and rear of the church identified this as one of the Cathedral ships sent from Earth to spread the word of God to the cosmos many years ago. A brass plate affixed to one side identified this one as The Cathedral of the Morning Star. It had been a doomed effort, as none had ever been heard from again. Miles beyond, over the alien sea, lightning branched in a distant storm.

A gust of wind tore through the trees and riffled the water as another surge of the tide washed over him again. The clouds briefly parted and he saw Jupiter, ribboned with color, filling nearly a third of the sky. Its terrible beauty was overwhelming. If there was a God to find, perhaps this was it.

The force of impact had cracked the satellite, producing a narrow fissure which ran a length of six inches near its top. The glass jar housing his brain was also cracked, leaking syrupy fluids. The fissure invited life: tiny crabs, crawling jelly-like organisms, alien mites looking for safety and reprieve from the carnivorous world, they crawled inside and, drawn to the sweet-tasting leakage from the jar, began to entangle themselves in the moonsilk.

Charlie sat there a long time, washed by the sea and hammered by unending sheets of rain, until it seemed inevitable that the rising tide would pull him from the sand and carry him out to the deeps. And then the drowned men rose from the water. There were six of them, their bodies bloated from long submersion, their skin pale and bloodless. Skin had sloughed off from parts of their faces, their skulls peeking through like dirty porcelain. They wore ecclesiastical robes, torn and muddy. Water streamed from their robes, what remained of their faces, what remained of their hair.

The six positioned themselves around him and lifted as with a single will. Then they carried him into the water, down the slope of the shore until it took them beneath the surface. They walked a short distance across the sea floor, the water above them reflecting a reddish, foamy light. The long fronds of plants and strange, stationary fish were pushed to and fro by the waves. The drowned men brought him to a breach at the base of the Cathedral ship, a great crack in the foundation leading into a crevice which zigzagged through stone and metal until opening in a completely flooded engine room, half of it crumpled into twists of metal and iron by the crash. A severed hand floated lazily by.

They carried him up submerged stairs until they broke the water’s surface, and he beheld the vaulted arches of the cathedral’s interior, stone walls decorated in frescoes besmeared with lichen, the twinkling lights of switchboards and circuitry lighting the darkness like candy-colored stars. Weak electric lights buzzed from a few alcoves, but the belly of the church was dark. The sound of dripping water echoed all around him, like a chorus of chirping bats.

The drowned men moved in a procession between the pews, up small flight of steps onto the apse, and placed him onto the altar. The pulpit stood a few feet away, looking over rows of pews enshrouded by darkness. Banks of dead computer panels lined the walls to one side. A rivulet of water leaked from a fissure in the ceiling far above and trickled over him, forming a little puddle beneath. A few feet behind the crack in the ceiling was the winding metal stairway to the bell tower. The bell sounded irregularly, as the Cathedral ship shifted under the heavy onslaught of the waves.

Charlie wanted to communicate with these things—ask them where he was, why they had taken him here, how they could still walk—but he had no means of doing so. The lights on his spines blinked in rapid coruscating patterns; he did not know it, but he was sending information through the long gulf, back to the moon, where Dr. Cull’s computer banks stood ready to receive it.

As the drowned men turned from him, off on their mysterious errands, one of them passed under the bell tower, and a heavy stone dropped from above and crushed it to a mangled stew. The stench of decay erupted from its ruined flesh. The rest of the drowned men proceeded around it, unaware or unmoved by the sudden death of their brother.

A spider, Charlie thought, and fear bloomed inside him.

Of course it was not a spider. Spiders don’t drop stones. It was an accident. And yet the fear remained. Something hateful was up there.

He waited.

Charlie had no sense of day or night. No sense of the passage of time other than the increasing sense of claustrophobia from being trapped inside this unmoving satellite in this dark, unmoving spacecraft. He wanted to sleep, but he no longer knew the difference between dreaming and real life. Could a being without eyes to close or a body to rest be said to sleep? Was all consciousness simply a dream?

Charlie could not even frame the question, much less answer it. But it seemed to him that he did dream, because his awareness of the Cathedral ship began to meld with his memories of an earlier time in his life, at the docks with Maggie, the woman who was kind to him and made him feel valued and purposeful. He followed these thoughts like a light at the far end of a tunnel; a network of tunnels, unspeakably vast, unspeakably complex, each running to different locations: some in the now, some in the yesterday, some, perhaps, in the days to come. Their proliferation confused him, so he focused on the light, the light which contained Maggie, until almost by accident he found himself in her home—a place he had never been. Her clothes hung around him, the thick, musky scent of her filling the small space like an atmosphere. She opened a door and stood frozen in fear and bewilderment. She was dressed in her nightgown, and she looked sleepy and vulnerable in a way he had never seen her.

Overwhelmed with longing and excitement, he tried to finish the crossing. He knew there must be a way to be there with her, physically, but he did not understand how it worked. She knelt down, her face drawn in shock.

“Charlie? Is that you? How can that be you?”

He pressed harder. He had the impression that the tunnels were soft, like earth, and might crumble if he pressed too hard. He sensed other things in here, too—crawling things—and that made him afraid.

“Where are you? You were supposed to come back to me.”

I tried. I’m trying.

“Tell me what happened.”

He couldn’t. But he found that he could reach through and touch her. Not in the way he might have before, but in a closer way. Relief washed through him as he felt her warmth. He could even smell the scent she wore: something woody and clean. A sweet ache—not quite sadness, but close—caught him in a place between frustration, yearning, and gratitude. He wrapped around her, feeling protected, loved, and safe.

Copyright © 2025 by Nathan Ballingrud

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...