- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

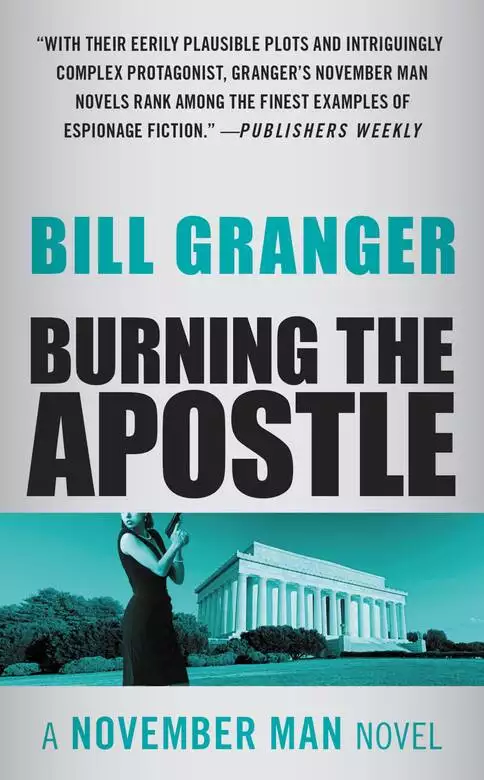

Synopsis

The Cold War is over--yet new, even more frightening wars have sprung up within our borders. Now, the field of battle for Devereaux, code name November, is to be found in Washington and Chicago itself. The conspirators are a rich, beautiful radical; a disenfranchised army officer; and a playboy U.S. Senator. They're backed by a mysterious Lebanese bank known as the International Credit Clearinghouse. And their goal is a shocking one: destroy the entire civilian energy industry in one bold stroke. In less than twenty-four hours, the November Man will have to defuse the most potentially devastating act of sabotage in history--and avenge an agonizingly personal injustice.

Release date: January 13, 2015

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 356

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Burning the Apostle

Bill Granger

At least G2 hadn’t screwed up. There was that.

Brig. Gen. Robert E. Lee was very angry as usual, and if G2 had not sent down the videotape cartridge when it did, he would have gone up there and chewed ass, and it would not have been about the videotape but the problem of trying to direct an intelligence operation in a building that should have been condemned thirty years ago.

General Lee wore no insignia of rank on his black pullover sweater. The empty satin epaulets attested to his power. He didn’t have to prove a damned thing.

He carried the surveillance videocassette in a manila envelope under his left arm as he swung down the empty corridor to the nest of offices used by this division of the Defense Intelligence Agency. People watched the way Bobby Lee walked—ambling sometimes, striding like now—and judged the advisability of being in the same corridor with him.

He turned into the bright anteroom that led to the other offices and stopped in front of the desk where S. Sgt. Lonnie E. Davis acted as gatekeeper.

Like all sergeants, Lonnie Davis was not afraid of generals. He gazed at General Lee for a full three seconds before pressing the security buzzer that admitted the general to the carpeted side of the room.

General Lee glanced at the computer screens, all blinking malfunction. With the computers down there was nothing to do.

“We got coffee?” the general said to the sergeant.

“We got coffee, machine in the next room, we hooked it up to the temporary line.”

“Goddamned wiring. Trying to run an op with this wiring would make a Russian weep.”

“At least the coffee machine works,” Sergeant Davis said. “You’ll like it. New coffeemaker came in from purchasing, I don’t know why we got it but we took it. Makes two pots at once, we can have regular and decaf,” Sergeant Davis said. His voice rambled as much as his words.

General Lee strode into the second room, glanced once at a terrified specialist four sitting doing nothing in front of his blank computer screen, and grabbed a ceramic mug. He stared at the machine for a moment. It was a beautiful fancy machine. Probably set DoD back five hundred bucks a copy. Bobby Lee poured regular coffee into the mug. The world was just too damned decaffeinated to suit Bobby E. Lee’s taste.

He followed a gray-walled corridor farther back into his realm until he came to the last office. He opened the door. Sp7c. Mae Teller, his private secretary, had arranged everything the way he liked it—six number-two pencils lined up like soldiers on the green felt paper pad in the exact center of his mahogany desk. There were two phones. The red phone on the right was very private, and the gray phone with six lines listed was not. He closed the door and locked it and opened the manila envelope. He inserted the black cartridge in the black VCR above the black-faced Japanese television monitor on the far wall.

He sat down behind his desk, opened a drawer, and took out the remote. He pointed it at the television set and VCR and pressed a button.

The black-and-white picture on the screen jiggled for a moment and then focused. The camera revealed the Red Line Metro underground platform beneath Union Station.

The Red Line was the most prestigious of the four Metro subway lines that snake across the District and probe into the near suburbs. It bisected the northwest quadrant of the District and reached into the posh suburb of Bethesda.

In the upper right-hand corner of the monitor, a digital clock ran in minutes and seconds, marking the real time of the recording and the actual time of day depicted on the screen. G2 had worked long hours overnight to edit out the garbage; this was what was left, what Bobby Lee would want to see.

0003:51, 0003:52, 0003:53.

The camera fixed on the sole passenger waiting on the platform. The focus was directed by a heat-seeking device, similar to that used in missiles. The heat of the man’s body directed the robot camera.

General Lee sipped his coffee in the semidarkness of the windowless room and watched the screen.

Above the hum of the videotape came the sudden sounds of steps down the escalator stairs. The escalator had been deactivated for the surveillance because it made too much noise on the soundtrack. This was a visual and audio surveillance.

General Lee put down his cup.

He stared at the waiting man who had turned to look at the escalator stairs. It was a familiar face.

It was Devereaux. Every night of the surveillance, Devereaux had come to this platform and waited until the last train. They thought he might have been waiting for someone to arrive by train, but each night, he stepped into a car of the last train without meeting anyone. They had followed him on the last scheduled train each night to his stop above Georgetown and a surveillance car had followed him to his apartment, and for ten mornings, G2 (officially, Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence [DCSINT]) had given Bobby Lee the videotape and it hadn’t been worth spit.“Come on, Devereaux, you son of a bitch,” Bobby Lee said to the monitor. He might have been cheering at a football game.

Devereaux was senior advisor for operations inside R Section. He was a little too senior to be messing around with secret meetings and letter drops and all the other stuff you do in the field. Too damned senior to suit Bobby Lee.

The robot camera fixed in a false stone above the escalator well jiggled, momentarily confused by the presence of a second heat source.

Bobby Lee saw the second man’s back. At last. There was going to be a meet.

The second man walked across the concrete platform.

The camera refocused, compromising on the two focal points. The picture was grainy and harsh.

The second man spoke.

The hiss on the videotape soundtrack overrode the speech.

“Damn,” Bobby Lee said. He punched the stop button on the remote. He pushed rewind and started again.

The second man walked backward toward the camera. Stop. Play.

Bobby Lee turned up the sound.

The hiss was louder.

“… something is going…”

Something something then “something is going” then something.

The second man turned in profile.

Bobby Lee stopped the tape. He knew the face, anyone in certain circles would have known the face. Carroll Claymore. Carroll Claymore. What the hell was this about?

Bobby Lee just stared at the screen, his mouth open as though trying to catch the words by inhaling them. Carroll Claymore was the pal, protégé, and confidant of Clair Dodsworth, who was one of the six or seven permanently important men in Washington. Clair Dodsworth had more money than God and sat on a lot more boards of directors.

And here was his protégé meeting at midnight on a Red Line platform with an intelligence officer for R Section.

Bobby Lee got up from his desk, still staring at the monitor. What the hell would this have to do with Clair Dodsworth?

He hit the play button on the remote control. He stood behind his desk with the control in his hand.

“I told you,” Devereaux said. “There’s not—”

Not not. Nothing. “There’s nothing” something something. “To worry about”? “I told you there’s nothing to worry about.” That’s it.

Bobby Lee filled in the words, watched the way Devereaux’s mouth moved, figured it out like doing a crossword puzzle in sound.

Carroll Claymore turned all the way around, looking back at the camera, looking at the silenced escalator he had just walked down. His face was ashen.

“Scared,” Bobby Lee said in the silence.

“Nobody’s coming,” Devereaux said. The firm voice. When you’ve got a scared source, you milk him, you mother him, you tell him fairy stories. Bobby Lee knew how to do it, it was part of the profession. Bobby Lee had seen Devereaux do it when their paths had crossed during the hot war in the middle of the cold war, back in Nam, back in the old days, when he was running an op for DIA and Devereaux was running for R Section and they knew about each other.

“Just lie to him,” Bobby Lee said to the videotaped Devereaux.

Good. Good.

Devereaux touched Carroll Claymore on the shoulder, brought him back to the moment.

Carroll Claymore said something. Bobby Lee frowned, stopped the action, rewound, played it again and again, but couldn’t make it out. Damned G2, damned cheap-shit equipment, how you gonna run an op, you got a building where the computers go down every other day, the goddamned roof leaks, you got Mickey Mouse surveillance junk? Christ, if the Russians had only known how fucked up we were, they would never have backed off.

Damn. Bobby Lee hit the stop button. He picked up the gray phone and dialed an internal number. Waited. Tapped the top of the desk, made the pencils jiggle in line.

“This is General Lee, I want Lieutenant Rumsfield.” Waited. “Lieutenant, I am watching this piece of garbage you people were supposed to edit down overnight and I can’t pick up a goddamned word, what kind of Mickey Mouse outfit—”

Waited, his face bright and hard.

“Yes, Lieutenant, I’m sure you can cover your ass with all that techno bullshit, but I am trying to run an op and I see a face on the screen and I can’t make out a goddamned word of what these people are talking—”

Waited, waited. Oddly, as he listened to the lieutenant’s explanation, he calmed down. What was the point of it? You chew out this candy-ass, and he covers himself with garbage about audio-enhanced electronic ironing and stuff nobody even heard of twenty-seven years ago when Bobby Lee was a bush-tailed second loo trying to learn the ropes. What was the point of it, except to vent a little frustration? After ten days they filmed the meet and now they couldn’t hear what it was about.

He said, “Next time you send down a tape, Lieutenant, you don’t send garbage, I can’t use garbage, am I making myself clear, Lieutenant?” Waited a moment, listened to the apology that was just another way of covering your ass, and then slammed the gray phone back on the receiver.

What was he going to do then? Like everything else, you improvise. The computers go down because of some outage in the basement, you hook up a temporary generator to keep the coffeepot boiling. Damned army was falling apart. But even as he thought this, Bobby Lee was smart enough to realize he had always thought this and somehow the army was still around, snafus and all.

He pressed the play button again. Carroll Claymore said something unintelligible and then pulled something out of his overcoat pocket.

Bobby Lee stared. Envelope, he had an envelope to give Devereaux, and suddenly his voice was as clear as the picture on the screen: “This is the last of it, I don’t want to do this anymore, this is what you wanted. Copy of the transfer from Lebanon. Into the account you wanted at District. This is the last of it.”

Devereaux: “Not the last. This is good and the next thing will be good. I’ll tell you when it’s the last of it.”

“Do you realize how powerful Clair is, if he suspected—”

“Don’t be afraid of Clair. Be afraid of me, Carroll—”

“But Clair—”

“The train’s coming. I’ve got to catch the train, it’s the last train of the night,” Devereaux said. “I’ll be here every night, Carroll, I want you to know that.”

There was more, but the sound track was filled with the rumble of the approaching subway train.

“… please,” Carroll Claymore said. His face was in profile to the camera again.

The right side of the picture was filled with the train sliding into the station.

Devereaux turned from Carroll.

The doors opened.

Devereaux waited, looked left and right.

“Our man’s on the train, Devereaux. We aren’t that stupid,” Bobby Lee said.

But then again, maybe Devereaux knew. Sometimes you could feel a thing when you were good enough, just feel it. But why would he know?

Devereaux stepped into the waiting car. He turned in the doorway and stared at Carroll Claymore on the platform.

The doors slid shut.

The train began to pull out of the station.

Carroll stared at the train rushing past.

The platform was empty except for the man in the overcoat. Devereaux would get off at the same stop as the other ten nights, walk down the same streets to his apartment building, and he would be followed all the way and it wouldn’t matter because he had something now.

And Bobby Lee had something now. Had a name and face and something something about money going into an account at District. What was District?

He thought of it then. He read the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and both Washington papers every day for the sake of filling up anew the hard disk of his memory. Something stuck out now. Clair Dodsworth on the board of District Savings Bank. That was it. District Savings Bank. Money from Lebanon going to a local bank. What the hell was this, was Devereaux shaking someone down after all those years of honorable service for R Section? Or was it something else?

Please.

Carroll Claymore was being squeezed and he was pleading with Devereaux to stop squeezing him.

“Devereaux,” Bobby Lee said aloud in the empty room. Devereaux had been messing into the affairs of DIA, and Bobby Lee had resented it and then become intrigued by it. He had set up the surveillance of Devereaux and followed him because Devereaux had started it, messing with DIA’s Mediterranean terrorist counterop for six months, probing this and that, and now there was money from Lebanon going into an account at District Savings Bank. Bobby Lee was supposed to find out all about Devereaux. Find out what R Section was up to.

And now this.

Bobby Lee stared at the dark monitor in the semidark room.

This was going right to Clair Dodsworth, the dog with the biggest balls in Washington.

“What are we getting into, Devereaux?” he asked the darkened screen.

Brig. Gen. Robert E. Lee humbly believed he was not afraid of anyone or anything after twenty-seven years of seeing everything and doing everything in every place in the world.

But he was uncomfortable just now.

Damned uncomfortable.

“I don’t want to go to the Round Robin. You see the same people in the Round Robin. Besides, everyone we know went to the play tonight and everyone we know is going to the Round Robin and we’re going to have to talk about the damned play again and I didn’t want to see the damned play in the first place,” Michael Horan said.

Britta Andrews smiled at him. They were in the car, in the big Lincoln limousine—because a Lincoln went over better with the public than a Caddy. That was something Horan would say and really believe when he said it.

Michael Horan was the junior senator from Pennsylvania. He had knocked off the Republican exactly nine years earlier. It had surprised everyone from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia all the way to the White House and the GOP National Committee. Right up to Michael Horan’s ex-wife and, truth be told, Michael Horan himself.

“They won’t talk about the play,” Britta said. “They’ll all come over to fawn around you and touch me to see if I’m wearing underwear.”

Senator Horan smiled at that and ran his own large hand across her lap and down her left thigh.

“You like being touched.”

“Women like to be touched when they invite being touched, but you wouldn’t understand that because you’re in the Senate and you think every woman is made to be touched.”

He shook his head then and removed his hand. “You see this one fag play and now you’re going to give me the lecture. I hate the lecture. I like women, I’m pro choice—and you don’t know the kind of heat I get for that from everyone from the pope on down to my father-in-law—and I support the EEOC and everything from Lesbian Awareness Week to gay motherhood, but I endured the play as well as I could for your sake and I don’t need that lecture.” He said this in a flat voice and every word counted for as much as every other word. It meant he was angry and he knew how to control it. Britta knew that. They realized they were talking too much.

So she kissed him. Haley, the driver, had heard it all, of course, but when people keep servants, they endure them by living their lives as though servants did not count. Haley watched the kiss in the rearview mirror. He saw the senator slide his hand along the stockinged thigh under the blue dress, and he thought about that, about what it would feel like. Haley was very loyal. He was more of a friend than a servant because he had been Michael Horan’s driver, and the driver of a politician hustling votes in hostile precincts is closer to the politician than even a chief of staff. He had been with Michael Horan back when they were in a Ford and they were living on Big Macs going up and down the endless valleys of Pennsylvania, talking to church groups and women’s clubs and the American Legion smokers and every damned thing and it had all looked so hopeless. Haley saw her push against him a little, not too hard, and the kiss was finished and the senator’s hand stayed right there on the stockinged thigh, and that little quarrel was over until next time.

“If we don’t go to the Round Robin, where do you want to go then?” Britta Andrews said.

“Sam and Harry’s. You’ll like Sam and Harry’s. It’s got a hetero crowd and everyone won’t have been at the play and we won’t have to talk about it—we won’t have to talk to anyone—and we can get a sandwich,” Michael Horan said.

“I ate today.” She was a size four by nature and still worked at it. In some shops, in some lines, she could even be a size two but she wasn’t a social X ray, she wasn’t small enough. She had blond hair and it was her real color. A blonde with blond hair, angelic features, blue eyes, great body, long legs, just a living, breathing doll, and she hated it sometimes and yet she didn’t hate it. She could quote Lenin and get it right; she would have preferred to be big and black and a man and she would have led the goddamned Symbionese Liberation Army.… Yet she was beautiful and that was useful too and she took pleasure in being beautiful. There was always this conflict about beauty and brains and will and desire. Like Michael’s hand between her legs right now. She looked straight at the rearview mirror and saw Haley’s eyes. She wanted to empathize with Haley because she really did care about ordinary people and what they thought, but the only way to treat Haley right now was to deny his existence. Let him look.

“I ate today but I have to eat again,” Michael Horan said.

“And have a drink.”

“No one ever has one. Never lie to yourself. A man who says he’s going to have just one is halfway to being an alcoholic.”

She liked that and gave him a quick peck of a kiss. She liked a lot of things about Michael Horan. He didn’t lie to himself or to her or to his ex-wife back in Pennsylvania, who pretended they were still married. “If you don’t lie to yourself, you make it easier.” Michael said that once. Michael had brains and guts. When you walk into an empty hall because your advance man screwed up and your handlers are embarrassed and one little old lady shows up and you make the best of it, you try to sell that one little old lady, then you know you have the guts. It’s what people who have never run for office can’t understand, all those columnists and thumb-suckers and pundits who were never elected to anything, they couldn’t begin to understand guts, but Britta could. She had guts herself, but she knew her courage was a different kind, much colder, much more reasoned.

Haley paid attention to traffic. Washington traffic dazzles at night because the streets and parkways and malls are so dark that the lights of the limousines stand out and form necklaces of light. Haley brought the car through the after-theater traffic, past the Willard Hotel and back north, then around N Street to a tow-away zone on Nineteenth Street facing south. Sam and Harry’s was an expensive bar-and-grill set back from the curb some thirty-five feet, a place with bright lights and noise and the manufactured common touch that is not cheap to obtain. Another kind of senator would have taken Britta to the kind of bar that John Towers used to drink in when he was the big man, dark and down and no questions asked, where a pretty girl can be groped in a booth without anyone seeing or telling, but Michael Horan didn’t lie. Not about Britta, not about anything that was important. He would lie about raising taxes, but that was something else.

Britta didn’t lie either. She had so much money that she never had to lie to anyone for anything. But she loved being with Michael because Michael had the other thing, the power that doesn’t come from inherited money but comes from grabbing people by the throat and getting them to vote for you. There is such beautiful poetry in that kind of power that Britta could be in love with the idea of it, even if she wasn’t half in love with Michael Horan.

Haley opened the rear door for them, and she stepped out first, the blue dress riding high on her thigh. Haley was looking at her and pretending not to look at her. She didn’t mind that, how could she mind being beautiful? Maybe Haley thought she was the senator’s bimbo. She couldn’t figure out what Haley thought, but then, she didn’t spend a lot of time thinking anything about Haley.

Michael came behind her. He took her arm. Part of not lying. The Philadelphia Daily News had caught him escorting some redheaded socialite to a Washington ball and manufactured it into a scandal, and then Michael Horan had faced a tough primary and won it by 60 percent. The papers back in PA had taken the hint: The public didn’t really give a damn about who Horan was screwing as long as it wasn’t a little boy and as long as he voted to put a surtax on incomes above eighty thousand a year.

Sam and Harry’s was one of the places that the important little people went to, along with the Monocle over by the Hill and that Mexican place in Northeast and three or four others. The important little people were congressional aides with their own domains and powers, as well as spooks from Langley and newsmen and newswomen from National Public Radio and the Washington Post and the Washington Times and people who put spin on stories for the sake of senators at $76,400 a year and others, all little, all envious of the wealthy and very powerful. These mandarins of the bureaucracy, the Congress, and the press were very small and mean and petty, and they counted because they were always there. Michael Horan and Britta Andrews had begun their relationship after they realized that they both, in their separate ways, despised the mandarins created to serve them.

So let them look, fawn, and feed their greedy envy. The important little people would tell the other important little people that Senator Horan was at it again: This time it was a blonde, a rich society type from a screwball family, and the man was so brazen that he took her right into Sam and Harry’s as if she was a trophy attesting to another good hunt.

The bar was long, wooden, and functional. The place was filling up. The rich wood colors were polished by bar lights that gave a false sense of friendliness and made wan faces glow warm.

Everyone in Washington had gone to the National Theater to see Robert Morse’s one-man show, Tru, based on the life and remarks of Truman Capote. The capital had almost no live theater, and each road show offering sent down from Broadway was attended as a religious exercise. It was the way peasants of another time gathered in their villages to hear a famous London preacher making a tour of the provinces.

The fawners, their envy contained in green eyes, pressed toward the senator and the senator’s “friend” and yet parted for them as they presented themselves and moved with majestic calm through the throng, plunging into the interior of the bar.

Michael Horan gave an easy grin. It said that he was famous and powerful but he was just like them, a regular guy trying to have a night on the town with the real people and not the phony baloneys in the Round Robin at the Willard Hotel. Britta turned to him, caught the profile of the grin, matched it. Hers was a little harder. Her smile had money, distance, and yet a keen political eye behind it. Her smile said she knew the names of the principals of all the European Green parties, had visited them, dined with them, gave them money, been respected by them… but was still willing to be a woman, a beautiful woman, endlessly desirable. It was a complicated smile, and the women among the little people studied it and knew it for what it was.

“Faneuil Hall without fish,” Michael Horan said under his breath and under his smile. He pushed her by the elbow.

“SoHo,” she said. “East Village. Maybe Little Italy on Saturdays in summer.”

“South Philly,” he said. “Thirtieth Street Station at night.”

“Newark,” she said. “Airport to downtown.”

“Cleveland,” he said.

“Gary, Indiana,” she said.

He thought about it. “Detroit.”

“Gary wins,” she said.

“Pierre, South Dakota,” he said.

“Have you ever seen Gary?” she said.

“You win,” he said.

One of the owners gave them a good corner table where they could share the illusion of privacy. The waiter was young and good-looking the way Irish boys are before they really discover beer and potatoes. He was staring at the front of her dress, guessing and wondering at the same time, and he did not have the skills yet to hide it. The frank gaze warmed her because he was good-looking, not like the grizzled Haley, and if she had been shopping for an ornament, she might have put him on her wrist.

Michael Horan notched up the grin. “Hiya.”

“I’m Michael, can I get you a cocktail?” Soft voice, very nice, and Michael the senator said he was a Michael, too, and the Michael who was a server said he knew and Michael Powerful asked where he was from and young Michael told him. It was all over in less than ten seconds, like working the crowd behind the rope at the airport before going on to Altoona and the next event of the day. Britta had grown used to it, but she was not comfortable with it. Elections, electioneering, precincts, polls… it fascinated her because there was power there that could be used, but the details were so boring and stupid. Cut through the details and just grab the power and hold it. She touched his hand on the table.

The waiter brought his Black Label rocks in a short rounded glass. He armed Britta with a chardonnay. She rarely drank and the white wine glass was a device, the way Robert Dole arms himself with a perpetually held pen in his crippled right hand. It invites people to keep their distance.

“Up the Irish,” Michael Horan said to her.

“Up the rebels,” she said. “Up the ANC.”

“Not too loud.”

“Loud enough,” she said. She made a pretense of tasting the chardonnay.

Michael Horan made no pretense. He took the drink with real thirst. The whiskey numbed and then burned. The whiskey spread across his wide, Irish face and gave it a false color of health. Micha. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...