Bride of the Tornado: A Novel

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Stephen King’s The Mist meets David Lynch’s Twin Peaks in this surreal, mind-bending horror-thriller.

In a small town tucked away in the midwestern corn fields, the adults whisper about Tornado Day. Our narrator, a high school sophomore, has never heard this phrase but she soon discovers its terrible meaning: a plague of sentient tornadoes is coming to destroy them.

The only thing that stands between the town and total annihilation is a teen boy known as the tornado killer. Drawn to this enigmatic boy, our narrator senses an unnatural connection between them. But the adults are hiding a secret about the origins of the tornadoes and the true nature of the tornado killer—and our narrator must escape before the primeval power that binds them all comes to claim her.

Audaciously conceived and steeped in existential dread, this genre-defying fever dream of a novel reveals the mythbound madness at the heart of American life.

Release date: August 15, 2023

Publisher: Quirk Books

Print pages: 355

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Bride of the Tornado: A Novel

James Kennedy

THE TORNADO KILLER

They called it Tornado Day but none of us knew what it was about. Mom and Dad wouldn’t tell us. Neither would our teachers. I never remembered having a Tornado Day before and neither did Cecilia or any of our friends or anyone at school.

All that week leading up to Tornado Day, Mom and Dad didn’t let us eat much. I wasn’t even supposed to feed Nikki. Breakfast was, like, one piece of dry toast. Lunch was a hard-boiled egg. Dinner was nothing. Late one night Cecilia and I were so starving we snuck some blueberry Pop-Tarts to eat in her bedroom, but they tasted wrong. I felt guilty somehow and ended up throwing most of mine out.

I fed Nikki anyway.

All that week we weren’t allowed to watch TV. We couldn’t even listen to the radio. Dad unplugged everything—the VCR, the stereo, the microwave, the alarm clocks, all the way down to the toaster and the coffee maker. He and Mom took the batteries out of the flashlights, the boom box, my Walkman, and even old toys Cecilia and I hadn’t touched in years. They unscrewed the light bulbs and put them in a box along with the batteries. The refrigerator was cleared out.

Mom and Dad stopped talking to us. It was the same with everyone else’s parents. Someone said it’s what you had to do to prepare. Prepare for what?

Nobody would tell us.

A killer was coming to town.

That’s what we heard from the other kids. We were all scared. We asked, is the killer coming for us?

The adults wouldn’t say.

The day before Tornado Day all the stores closed early. We didn’t have to go to school. The house was quiet except for the patter of rain and Nikki meowing in the kitchen.

It wasn’t much of a holiday.

Growing up, when there were tornadoes, Mom and Dad and Cecilia and I would all run down to the basement with candles and food grabbed from the kitchen, and when the electricity blacked out we’d light the candles and set them all around the cold gray basement until it flared up like a cathedral. The candles pushed back the darkness and made it dance, colors multiplied, became richer and warmer. We’d hear the tornado raging outside, pounding at the doors and windows, shrieking like it was mad at us personally, but I felt safe, locked down in the concrete basement, cozy and cared for, but just dangerous enough for me to feel a thrill.

I liked the tornadoes because they forced Cecilia and Mom and Dad and me to hang out together. We played Monopoly and Clue, we listened to our little transistor radio, Dad told funny stories—I wanted more tornadoes, more thunderstorms, because I wanted us to be close like this all the time.

But when the lights flickered back on, when the all-clear siren sounded, Mom and Dad would get up from our game too quickly, “Finally!” they’d say; Cecilia, too, would bolt up the stairs, and then I would be left alone on the basement’s concrete floor with the abandoned game, surrounded by old exercise equipment and Halloween costumes and yellowing paperbacks, feeling a little disappointed because it was finally my turn and nobody wanted to play anymore.

***

It was still dark outside when Mom woke us up. It was a raw April morning, black and wet. Drizzle and fog and low, heavy clouds.

It was four a.m. Way too early. The electricity was back on, but after a week without it the light from the hallway looked jarring on the carpet, it cut too bright and hard through the dark. I stayed under my blankets. I had secretly put new batteries in my Walkman and it was under my pillow and the headphones were still on my ears. I’d fallen asleep with it on again. Nikki was awake but she was just staring at me with her yellow slit eyes. I stroked her and she purred but I already knew it was going to be a bad morning. Rushing my shower while Mom banged on the door. The bathroom stinking of Cecilia’s toxic hair spray. Everyone fighting.

A normal day.

Not normal, though. Usually, Dad was already off to work before any of us woke up—I never saw him in the morning, I’d just come into the kitchen and see his bowl of milky cereal dregs in the sink, which always depressed me for some reason. But this morning was wrong, everyone’s schedules collided. Dad was clunking around in the kitchen, blinking at us like he was still half asleep. Mom usually slept in, but this morning she was up and ordering us around, looking frazzled in her ratty blue robe and huge curlers.

She’d laid out two dresses for Cecilia and me to wear to school for Tornado Day. I’d never seen these weird dresses before. They were old-fashioned flower-print things with puffy sleeves and lace trim. Like something a pioneer girl would wear in an old movie.

Cecilia slammed her bedroom door. There was no way she’d wear that crappy dress to school, she shouted at Mom. Everyone would make fun of her, she said.

I didn’t want to wear mine either. The dresses smelled sour, like they’d been boxed up somewhere for a long time. But I put it on anyway. I cleaned out Nikki’s litter box as Mom and Cecilia yelled at each other. I kind of hated myself for it, but whenever Cecilia fought with Mom, something in me wanted to be really good, to balance the family out.

Cecilia won. Mom said go ahead—fine, don’t wear the dress! But you’ll be sorry! Now I was the only one wearing an ugly, stale-smelling dress but the bus was already pulling past our house, way too early. There wasn’t time for breakfast, not even to grab a bite on the way out. Cecilia and I had to run to the corner to catch up with the bus. We got on and its doors hissed shut.

The morning was still as dark as night.

It turned out everyone had dressed up for school that day. All the boys wore awkward suits and all the girls wore old-fashioned dresses.

Cecilia stuck out in her normal jeans and her pink sweater. She went to the girls’ bathroom and stayed there. Mr. McAllister asked Mrs. Bindley to go in and get her. Some of the popular girls were snickering at Cecilia. I happened to be standing near them when Mrs. Bindley came out of the bathroom, pushing Cecilia along by her elbow.

As they walked past us Cecilia said to me, “You just keep on laughing.”

***

We were going to meet the tornado killer.

What tornado killer? None of us knew about any tornado killer. That’s how you know he’s a good tornado killer, the teachers said—when’s the last time you even saw a tornado? We had to admit, not since we were little. But, we said, you always heard about tornadoes in other towns! Exactly, the teachers said. But not here. Would we recognize the tornado killer? They said no, it’s against the law for the tornado killer to actually come into town. He does his work outside city limits. But today is a special occasion, they said. Today is Tornado Day.

Some of the younger kids were scared. They begged their teachers, please, please, no, we don’t want to meet the tornado killer.

Everyone meets the tornado killer, was the firm reply.

We went to our homerooms to wait for the tornado killer. Mrs. Bindley turned off the lights and told us to put our heads down.

Ridiculous. We were sophomores. I hadn’t been told to put my head down since fifth grade. But there’s only one big school building in town, so even though our high school was in a different part of the building than the elementary and junior high schools, the teachers still sometimes treated us like children.

The dim classroom smelled like wet coats, old shoes, and body odor. The radiator clanked. It felt like we were in some kind of trouble.

“Tomato killer,” said someone.

Some kids snorted.

“Cuthbert Monks,” said Mrs. Bindley, “another word and you’ve got yourself detention.”

I glanced over at him. Even Cuthbert looked surprised at this. It wasn’t like Mrs. Bindley to overreact. But it seemed like she hadn’t slept much either. She kept touching her necklace, turning it over and over.

Cuthbert Monks smirked across the room at Ned Barlow but put his head back down. Cuthbert and Ned had been separated months ago, and Jimmy Switz, he’d been moved over to Mr. Pedrowski’s homeroom entirely.

They were all obnoxious.

I kept my head down. My desk was near the window. I looked out at the dark, gray, wet day. Cecilia was in Mr. McAllister’s room downstairs—she was a year ahead of me, a junior, but I was thinking maybe I could go down to her room, to let Cecilia know that I hadn’t actually been laughing with those other girls, and maybe I could offer to switch clothes with her, or maybe we could even call Mom and have her bring in Cecilia’s dress for her—and then I saw lights moving outside.

The lights got closer. Wobbling out of the dim woods, coming toward the school. I couldn’t see very well through the watery windows, but there were about a dozen men, the white beams of their flashlights sweeping through the darkness, swinging and clashing. Like a little parade, though nobody seemed very happy to be in it. They were coming toward the school.

They were carrying a box.

***

I had so many friends when I was younger. Cecilia and I had been in a group with Lisa Stubenberger, Sadie Hughes, and Danielle Lund who roamed around town and hung out at each other’s houses. There was an end-of-childhood in-between time that almost lasted into my freshman year, when we would goof around with dolls but also play truth or dare, when we’d discuss what boys were cute but also pretend to have superpowers. We had our fights but they never lasted. We’d all known each other since I was in kindergarten. We had always just hung out.

Then everyone became a little more individual. Lisa started dressing like she was a preppy and Sadie began dressing what Mrs. Bindley called “provocatively” and they competed over the same boys. Cecilia got into Archie’s clique and began saying mean things about the others, and Danielle started working at her mom’s restaurant all the time and treated us like we were immature. Everyone went their own older way. I was left behind.

It was around then that I found some trashy books at the library. I never checked them out, I just read them in the stacks, alone. In those paperbacks, people didn’t act like anyone I knew, these people were more heartless, more brutal, but friskier and more alive, and it was while reading these books that I started to think that being an adult might be better than just being me. The adults in my own life were boring, but the adults in these books were hungry and fascinating and daring in ways that didn’t feel allowed.

I didn’t always get what was happening in those books. They always seemed like they were building to some huge revelation, some exhilarating emotion. But when the crucial time came, it seemed the story would skip that revelation, that emotion. I didn’t understand what happened when the book was silent, the secret action that seemed to change everything.

The teachers made us get into lines and walk down to the gym. The bleachers were pulled out and there was a small stage with a lectern, like we were about to hear from some motivational speaker or somebody who was going to tell us stay off drugs.

Nobody told us anything about what was going to happen next. Kids whispered to each other, but then the teachers would shush them and give them hard looks. The fluorescent gym lights buzzed. It felt too early to be in the gym. Everything had the remote tingle of a dream.

I hadn’t eaten since yesterday. I could feel my blood sugar running down, not exactly like I was going to faint, but I felt weak and kind of detached from what was happening around me. I just went along with it. The teachers separated the girls from the boys for some reason. Cuthbert Monks found Barlow and Switz in the crowd and they were shoving each other and some other kid until Mr. McAllister broke it up. But it wasn’t as rowdy as usual. It felt like everyone was a little nervous.

People chattered with anticipation around me. I felt like I could go straight back to bed. In the muddle I got separated from the rest of my homeroom and I ended up having to sit with a bunch of freshman girls I didn’t even know.

I spotted Cecilia up the bleachers. She was sitting with the same junior and senior girls who’d been snickering at her before. Now they were all together, whispering in a conspiratorial way. I tried to catch Cecilia’s eye. One of the laughing girls saw me and murmured something. Cecilia said something out of the corner of her mouth and they all laughed so hard Mrs. Lubeck had to shush them.

Come on, Cecilia.

I’m on your side.

Sophomore year was a disaster so far, but Cecilia just said to me, “The reason you don’t have friends is because you don’t put yourself out there,” and I was like, put myself out where? But maybe Cecilia was right. When I was younger I had liked being in plays…maybe I could be a drama club kid…In January there were auditions for the big spring musical. I went to try out.

I didn’t know anyone at the auditions. I sat in the dark back of t

he auditorium. All the girls got up one by one to sing a song from the play, which was Oklahoma!. I realized too late that I should have prepared. Like, actually have read the play. One after another, girls got onstage and sang, “I’m jest a girl who cain’t say no! Kissin’s my favorite food!” as I sank deeper and deeper into my seat. I got up and left before they even called my name.

Cecilia was right, though. I see the drama kids messing around together all the time. They are always having a ball.

The men came into the gym.

I didn’t recognize them. Even in a town as small as ours, you don’t know exactly everyone. The men had put their flashlights away but they still had the box.

The strange box was as large as a refrigerator, wooden and old and complicated, with carvings and handles and rails, and you could see it had been painted over a hundred times, because where one color had flaked away there was another color under it, and another color under that, and the paint was bubbled and faded and cracked.

The men set the box down on the stage. All of them walked away except the tallest man. That man put a key in the box and unlocked it.

Then the tall man also walked away, very fast.

None of us said a word.

The lid of the box started to move.

Something was trying to come out.

I held my breath. Everyone in the bleachers around me did too. Nobody knew what it would be.

But of all the things we had expected—of all the things any of us imagined might’ve come out of that box—we were all wrong.

It was a boy.

He climbed out. He blinked and squinted at us.

I thought, They had to be joking.

This was a tornado killer?

When Cecilia began going out with Archie, she got mean. Which made no sense, because Archie himself was so nice—like, too-good-to-be-true nice. Still, going out with Archie raised Cecilia to a new level of popularity, and it unleashed something merciless in her. For some reason she went scorched-earth against the rest of our old group, calling them boring sluts and stuck-up bitches. And there was enough awkward truth in what she said about Lisa and Sadie and Danielle that it was unforgivable.

As Cecilia’s sister, I wasn’t forgiven either. We were both frozen out. Unfair but whatever. Cecilia did let me hang out with her new friends in Archie’s popular clique, even though they were all juniors and seniors. I was just a sophomore.

One year makes a difference, though.

So I spent that year mostly alone. I played video games at the bowling alley alone and my high scores stayed on the machines unchallenged. I swam in the quarry alone, even though people had drowned there, but plunging down to the bottom of the cold water felt so good. I went to the thrift store alone and I bought clothes that felt haunted, and books that felt forgotten, and knickknacks that seemed from another planet, and I couldn’t understand why I was the only one from school who’d get stuff there.

I hung out in the library alone, reading those books I was too shy to check out. One of them had a girl who was a beautiful runaway. I kept going back to that book. The girl’s parents were nice, her life was fine, but she ran away and the book was on her side. I liked that. This girl was innocent but kind of heartless. Cutting straight through her life, using and taking.

I thought about what I read. I did a lot of thinking back then. I liked being in my own mind.

When you’re alone, everything feels more intense. But it also feels like you’re only

half experiencing it.

The tornado killer stood onstage.

He seemed like he was about my age.

Some of the kids were giggling and murmuring. Not just Cuthbert Monks and his buddies. Even the girls around me seemed skeptical.

I guess I’d expected a tornado killer to be older. Or bigger. Or maybe not even a person at all. But this boy could’ve been someone from school. A year older than me, tops. Maybe a few inches taller. His sandy-brown hair was mussed and his clothes seemed like they were from ten years ago, a purple and green plaid shirt that didn’t fit him and gray corduroy pants that didn’t match. He didn’t look comfortable in them.

He looked like some shy animal that’d been flushed out of its hiding place.

I glanced at Mrs. Bindley. She was touching her necklace again. There was going to be trouble. I could feel it around me. Now that everyone realized that the tornado killer wasn’t much different from us, that he was just some kid—they felt cheated.

The tornado killer

must’ve sensed this. When he’d first stepped out of the box and looked up at us, it was as if he’d expected us to welcome him. Like clap or something.

Nobody had clapped.

Missing breakfast was catching up with me. I felt far away from everything in the gym, my stomach hollow. The tornado killer shuffled through some multicolored three-by-five note cards. He was peculiar looking. He had a wholesome but uneven face, almost kind of like an all-American midwestern boy, but then he’d turn his head and he looked raw, on the edge of ugly. Something not fully formed.

He glanced up at us, scanning us row by row. My head buzzed as if there was some tiny thin noise just outside my hearing. But the gym was quiet, everyone waiting for the tornado killer to begin. The tornado killer went back to his cards and fumbled one. It fell to the floor. He stared at it, for some reason not moving to pick it up.

Jimmy Switz said, “Tomato killer.”

Such a stupid joke. Technically it wasn’t even his. But it got a laugh. Not because it was funny. But because the crowd wanted to send the tornado killer a signal. They didn’t like him. People were beginning to talk openly. The teachers were losing control.

I felt distant from all of it, a little light-headed from a week of eating almost nothing. The tornado killer shifted his weight and glanced over at his box, like he wanted to go back in. Yeah, he didn’t want to be here, okay, I felt for him. I wouldn’t want to be up there either.

The tornado killer took a breath. He looked at his cards again, then back up at us—whatever it was he’d come to say, okay, he was going to go ahead and say it—he leaned into the microphone and announced:

“I AM YOUR CHOSEN ONE!”

Silence.

Someone yelled, “Dork!”

“But what was I chosen for?” said the tornado killer, reading off his note cards. “What mysterious aristocracy do I belong to, that no man may look into my eyes without sublime terror?”

“Ass.”

“For this reason: I am the tornado killer!”

“Ass!”

“But how did you know I was your, ah, uh, chosen one?” said the tornado killer, faltering a little. “Take your pick from the multitude of signs and wonders that attended my birth! There was, of course, the matter of my unsettlingly beautiful eyes.”

What the?

“Or my uncanny ability—”

“—to be an ass,” said Cuthbert Monks.

Snickering. The tornado killer coughed stiffly, read on:

“Or my uncanny ability,” said the tornado killer, staring at an index card. “My uncanny ability—”

“I have the uncanny ability to finish a sentence,” remarked Cuthbert Monks.

More laughter.

“My uncanny ability,” pushed on the tornado killer, “my uncanny ability to soothe the winds—or whip them into a fury—ever since I was a small child—simply by the, the sound of my voice, the twitch of my, uh, my eyes—”

Somebody threw a pencil at the tornado killer. It bounced across the stage, past the lectern. He acted like he didn’t notice. It’d taken only a minute for the tornado killer to turn everyone against him. He didn’t seem to get that. My heart kind of went out to him. He obviously didn’t want to make this speech.

Still, he was pushing through it. He put his hand in his chaotic hair and slowly raked through it, his hand remaining on the back of his neck as he stared down at the card. Then he smiled a little, as though he knew this was ridiculous.

“For many years I have dwelled alongside you,” read the tornado killer. “With these legs I have walked the land around this town, circling you. With these eyes I have watched over this town, contemplating you. With these hands I have warded tornadoes away from this town, protecting you. And now today, at last, I am allowed to come among you, and meet you face to face.”

He looked up from his cards.

“I am the tornado killer.”

Most everyone had stopped listening. It didn’t help that up until now, the tornado killer read these words without conviction. His eyes hunted through the crowd again, as though looking for somebody in particular. A wobbly feeling crept up from my stomach. Around me people were just blatantly talking. Tornado killer? I couldn’t imagine this kid even beating up another boy, much less killing a tornado, whatever that meant. Maybe, a girl near me was saying, this was all some kind of comedy thing? But the joke didn’t make sense.

“The day that I was birthed into the world,” the tornado killer went on, gaining steam, “my raw powers instinctively grappled with the radio waves that flow and pulse around us all, bending them to make every radio in town broadcast my newborn cries. Purely by unconscious ability, I reached into the heavens and pulled down hailstones

as large as chicken eggs, smashing windows and denting roofs. And thus I put it to you all: if my powers can even shape your airwaves, if my powers can even dominate your unruly skies, what might I do to a tornado? What might I do?”

“You might shut up?” said Tina Molloy, loud enough for the tornado killer to hear but not so loud the teachers could pinpoint who’d said it.

But the tornado killer was going for broke now. Maybe he was nearing the end of his weird speech and just wanted to get it over with.

But something felt wrong, my heart was racing, why?

“Only the pure can kill a tornado,” the tornado killer declared. “For this reason I must remain outside city limits. For this reason I must live alone. For this reason I have not walked among you, not until this sacred day. Although I have watched all of you from afar.”

He looked up at us again, his eyes scanning the crowd again.

Awkward silence.

“Wait a second,” shouted Cuthbert Monks.

“Pipe down,” said Mr. McAllister.

“No, no,” said the tornado killer, as if relieved. “By all means, I welcome some Q and A.”

“What do you mean, watched us?” said Cuthbert Monks. “Like spying? You’ve been peeking into windows and stuff?”

The tornado killer looked down at the lectern.

“I have watched all of you,” said the tornado killer softly. “Even you. I have watched you ever since you were a small boy.”

Cuthbert Monks crowed with delight.

“Okay dude,” he said. “Gay.”

A lot of kids laughed.

The tornado killer looked up, and stared at Cuthbert Monks.

The laughter died in everyone’s throats.

The tornado killer hadn’t truly looked at us before. Not like this. Not with these eyes: one a deep glittering green, the other a fierce and furious blue. It was like the eyes of two different murderers had been stuck in the head of one boy, almost glowing, throbbing as if at any moment they would leap out in two different directions. They were hypnotizing. They were terrifying. But nobody could look away.

The tornado killer stared at Cuthbert Monks with his nightmare eyes for a long time.

Then he said:

“If you know of a better way for me to understand the town I have protected ever since I was six years old—killing tornadoes for the sake of you and everyone you know on essentially a daily basis—then by all means, I’d love to hear about it.”

Cuthbert Monks and the tornado killer stood, eyes locked.

An agonizing second passed.

“Sportsman, Cuthbert?”

It took me a moment to register that the tornado killer had used Cuthbert Monks’s name. How did the tornado killer know his name?

Who was this kid?

“What?” said Cuthbert.

“I asked you, Cuthbert Monks: are you a sportsman?”

Cuthbert Monks didn’t answer.

“Captain of the wrestling team,” yelled Jimmy Switz. “He’s all-state.”

The tornado killer didn’t acknowledge Jimmy.

Another second ticked by.

“I wonder,” said the tornado killer, “I wonder what sport you were playing at the quarry, with your friend Jimmy Switz over there, on June seventeenth last year.”

An off-balance moment. What the tornado killer said was so specific and yet so vague. But seeing how Cuthbert’s face changed, it was damning. Still, I didn’t understand why Cuthbert did what he did next—and trust me, I don’t want to know what Cuthbert and Jimmy were up to at the quarry last summer—but at that moment, several things happened.

Cuthbert Monks rushed the stage.

The tornado killer looked up.

His eyes fell upon me.

Then locked on me. Like he recognized me.

The bottom dropped out of my stomach.

The electricity went out. The gym was plunged into darkness.

And then we heard the rising, grinding wail of the storm alarm—the siren that

meant a tornado was near.

Darkness, confusion, everyone shouting, pushing—

Chaos at first, all of us scrambling to get off the bleachers in the pitch black. I was bumped and shoved. Somewhere in the darkness Mrs. Bindley and Mr. McAllister were saying things but I couldn’t understand what, I couldn’t understand anything over the yells echoing throughout the gym, I think they were trying to calm us down but there was only so much they could do in the dark.

“It’s all right,” Mr. McAllister called out over the noise. “The tornado killer is here. Right now this school is actually the safest place in town.”

But Mr. McAllister’s voice sounded flattened and far away, somehow wrong. I felt wrong. When the tornado killer looked right at me it scrambled something in me. Like his eyes went into me the wrong way.

I didn’t know where the tornado killer was now. I didn’t know where anyone was. It was an unsettled darkness, some littler kids were crying and teachers were trying to soothe them but everything felt jumpy, intense. Some kids were excited, the way people get excited by any disruption to school. I kept bumping into others in the darkness and my body felt like it was full of that thin noise just on the edge of hearing, a noise about to break through. Nothing electric seemed to function: the microphone had cut out, the emergency lights didn’t switch on, the men’s flashlights apparently didn’t work anymore either. I heard the wind whipping around outside, the clunking and rattling of things getting tossed around, a mounting noise like a jet engine howling, and the wailing alarms. I was looking for Cecilia, looking for someone I knew, but I couldn’t find anyone. I stumbled over a book bag. All the students in the school were packed in the gym, from kindergarteners up to seniors, and I heard Archie’s voice nearby, he was comforting some younger kids, being jokey with them (“Wait, what time is it? Almost six? Oh man! Yeah, I’m usually not even awake at six either! What do you like for breakfast? Raisin Bran? Aw, me too!”) and that was classic Archie, being helpful without being prissy about it, he was just naturally decent, why was he so into Cecilia, who frankly could be a weird bitch sometimes? Kids sat and whispered in little groups, some boys were sneaking around and causing trouble, and Jessica Hauser and Bobby O’Brien were totally making out under the bleachers. I felt knocked out of place, whatever my place was.

I heard a muffled sound nearby.

Cuthbert Monks said, “Lock this fucking freak up.”

“Yessir, we’re safe as houses,” declared Mr. McAllister over the alarms. “Isn’t that right, tornado killer?…Eh, tornado killer?”

I heard what sounded like the tornado killer, not far from me in the darkness. A strangled shout. The tornado killer—

I stumbled toward where I thought the sound was coming from. There was nobody there.

Then I heard maybe him behind me, grunting and struggling, like he was being dragged away.

“Probably already out there right now, wrestling those tornadoes.” Mr. McAllister chuckled nervously. “Okay, settle down, guys.”

I shoved through the crowd, trying to find the tornado killer, trying to find Cuthbert Monks—I thought I heard the tornado killer try to call for help again, then he was silenced, it seemed they were headed for the stairwell but now I was pushing the wrong way through everyone, bodies closed in around me, I couldn’t get at him and I heard the tornado killer struggle and shout, and then a door slammed and I couldn’t hear him anymore, I didn’t know where I was either, I was blundering through some elementary schoolers,

I plowed into a little boy by accident, he started crying, I tried to comfort him but I was also trying to get a teacher’s attention, to tell them the tornado killer wasn’t out there fighting tornadoes, that Cuthbert Monks had him for some reason, he was taking him somewhere, to lock him up and there was a mounting rushing sound in the darkness all around me, a buzzing like something huge and invisible swooping in, I tried to find Mrs. Bindley or Mr. McAllister or any teacher, I unexpectedly found Cecilia, I grabbed her—

“What? What?” said Cecilia.

Then the tornado hit, I felt myself lifted up on pure air, and then we were all blown out of the gym like we were made of paper.

I was blasted out into the main hallway, books and papers and desks and a kid flew past me, hurtling down the corridor, locker doors were torn from their hinges, walls collapsing, windows cracked and shattered and bled down the hall in glittering streams, a flying chair clipped the side of my head and I flew out of the school and up into the sky as though I’d been shot out of a gun.

I tumbled through the churning air. The world came at me in flashes. I blacked out and then I was flopped out on the grass, on the playground behind the school, staring up at the monstrous spinning tornado.

There were others sprawled in the field all around me. I didn’t know if they were alive or dead. The roar of the tornado was deafening. My head throbbed from where the chair hit me. I was surrounded by floating papers and fluttering scraps of books and heaps of desks, staring at our school and how the tornado was already relentlessly taking it apart, whipping around faster and faster, a tremendous howling blur, ripping the roof into ribbons that went flying into the air, strips of roof fluttering up like tentacles reaching to the sky and waving around—then the entire roof lifted off the school, the school just shrugged it off like it didn’t need a roof anyway, and then the tornado was rabidly feeding on the school, tearing off bricks, slurping out the plumbing, chewing the girders, the entire building getting bent, twisted, liquefied, gurgled, and spit into the sky.

I was going to die. We were all going to die together. We were too close to this uncontrollable killing thing. The tornado whipped around with vicious energy, chewing through the wreckage, tearing apart the jumbled tables and cracked chalkboards, but almost with a kind of furious intent, like it was hunting for a retainer it’d accidentally thrown away. I lay among the shredded book reports and wrecked dioramas, my head ringing, too terrified to move.

Our school was destroyed.

Except for one thing.

A stairwell of the school still remained. Plus a little bit of the third floor hallway jutting out of it, where the janitor’s closet was. But there was no third floor anymore, no second floor, no school—just the stairwell’s shell of bricks and girders supporting the janitor’s closet, three stories up in the air, alone.

I saw the door rattling.

Someone was in there.

Lightning shimmered in the dark green sky around us. Everything felt unreal. I tried to scramble up, to run away—

The tornado churned forward and engulfed the stairwell and the janitor’s closet, swirling

around it as though ravenous.

It ripped the door off.

The tornado killer was inside the closet, crumpled against the wall. His face was bloody. He held up a trembling hand as if to say: please, no more.

The spindly mortar and metal structure that held up the closet collapsed. The tornado killer fell out.

He dropped two stories and hit the ground.

His body lay in the grass. Not moving.

The tornado blasted toward him.

The ringing in my ears had receded enough that I could hear the little kids crying and the teachers shouting. The tornado killer was about to get shredded. Someone should’ve helped him. Nobody did. I stared at the tornado killer. This boy was all there was between us and this monstrous spinning funnel roaring out of the darkness. The tornado killer stirred. Other kids looked away. As unpopular as he had made himself, nobody wanted to see what they all knew would happen next. What would happen to all of us.

We were all wrong.

The tornado killer raised his head from the dirt.

Shakily, he lifted his left hand.

The air changed.

The tornado staggered back—still swirling, but woozily swaying, dipping back and forth—and the tornado killer leaped up. Keeping his left hand raised, he sliced his right hand through the air.

The tornado reeled!

I felt the air change, prickly and hissing. The tornado killer advanced on the tornado, waving, pointing, and punching. His face was cruel and his eyes shone.

The tornado wobbled, staggered, screamed!

I choked, I couldn’t breathe, my body felt as if it was floating.

The tornado killer then raised both hands—gathering up the whirling tornado into a frenzied, narrowing cone—he stretched it taller, narrower—thinner—like it was a string of taffy—thinner—a long, thin, frantically spinning column—the tornado killer drew his hands closer together—the column tightened, spun faster—faster—closer—the tornado was a wildly wobbling, infinitely lengthened thread—the tornado killer clapped—

POP

And there was nothing left of the tornado but the stirring of grass at our feet.

Silence.

The tornado killer stared at all of us with brutal eyes. I was afraid he would look

at me again.

He didn’t.

“An easy one,” he said.

Then the tornado killer limped away.

Nobody followed him.

But I wanted to.

THE GIRL WITH THE CAT AND THE KNIFE

Igrew up here, in the middle of what you’d call nowhere. There isn’t really any other town for miles, just the highway and cornfields and midwestern plains. Sometimes, when I’d see our one bus station out near the edge of town, I’d think about what would happen if I got on a random bus and left.

Not tell anyone. Nothing was stopping me.

I’d never been out of town. Not even for vacation. It’s not like I hated home, though. I didn’t hate my family. I didn’t hate my life.

But waking up in the middle of the night, sweating, why did I feel so panicked, short of breath, I didn’t know why, what was wrong with me?

Then I met the tornado killer.

There was a radio station I listened to late at night.

It was from a city a hundred miles away. The DJ called himself Electrifier. He had a low purring voice and the music he played was alien, intense, unlike any music anybody around here listened to. Sometimes the music felt frightening, I didn’t know why. Or it felt goofy but I didn’t get the joke. Often nobody sang in these songs, or if they sang it was in a foreign language, or the voices were samples from movies, and the music sounded like a machine pulsing and the repetition put me in an expanding trance, especially late at night, it made my brain open up and feel different. The way Electrifier talked between songs wasn’t how most DJs talked, he spoke in shadowy fragments about things I didn’t understand but it was soothing and mysterious, like there was a secret party in the city happening somewhere without me, but maybe I’d find out about that party if I went to the city, and when I listened to Electrifier’s show I imagined I was in the city, I’d close my eyes and think about walking down the city streets at night, different lights blazing all around me, strangers passing me, and maybe I would catch some stranger’s eye and we’d feel each other’s weirdness for a moment and then we’d move on, and the late-night radio felt like that to me, anonymous and risky and intimate.

Nobody at school liked that kind of music. I didn’t like their music either. They wanted slow songs about feelings that they could cry to while they clung to each other at dances.

I wanted something clean and robotic, empty and chilly but full of power, not for my brain to listen to but my body to move to, that I could dance alone to in a dark room somewhere, or a room full of other people dancing alone but watching each other. I thought of that bus station, of getting on one of those buses and running away to that exhilarating somewhere, as I was dancing alone in my room, feeling a little stupid, but it also felt important, like I was practicing.

Ever since Cecilia’s and my group broke up I biked around town alone, listening to Electrifier shows I’d taped off the radio over Dad’s cassettes of crappy classic rock. He never listened to those tapes anymore anyway. Sometimes where I started and stopped recording there’d be a gasp of Dad’s music, or I’d hear it echoing faintly underneath.

There was one song that Electrifier played a few times that I didn’t exactly like, but I couldn’t stop listening to. The name of the song was a girl’s name. A man sang it and the words seemed to be about something wild and thrilling, but he sang them in the flattest way, weary and jaded. I listened to that song again and again.

I wore those tapes down to nothing, trying to figure the songs out.

I listened to Electrifier on my Walkman while I biked around the forest trails. I liked being in the woods, not just because of the trees and ponds and quiet calm, but because I saw that other people came into these woods at night. I’d see like a rotten old mattress with bottles and wrappers around it, some dirty clothes left behind, and I wondered who would come here.

I broke into abandoned houses. There were isolated empty houses from when more people used to live around here. I wondered about those broken-down houses because I’ve never seen anyone move out of town. Or move into town, for that matter. Sometimes I’d find old clothes and books in those houses, or there would be antique ovens and refrigerators, and all of it would be overgrown weeds

and crawling with insects.

I took stuff from those houses. A glass doorknob like fancy crystal. A red leather photo album with faded pictures of some generation-ago family. A little pearl-handled knife I began to carry around.

I figured out how to get into the storm drains. I climbed to the top of the water tower. I didn’t know what I was looking for, but I liked the feeling of looking.

I had a private mystery I was trying to solve.

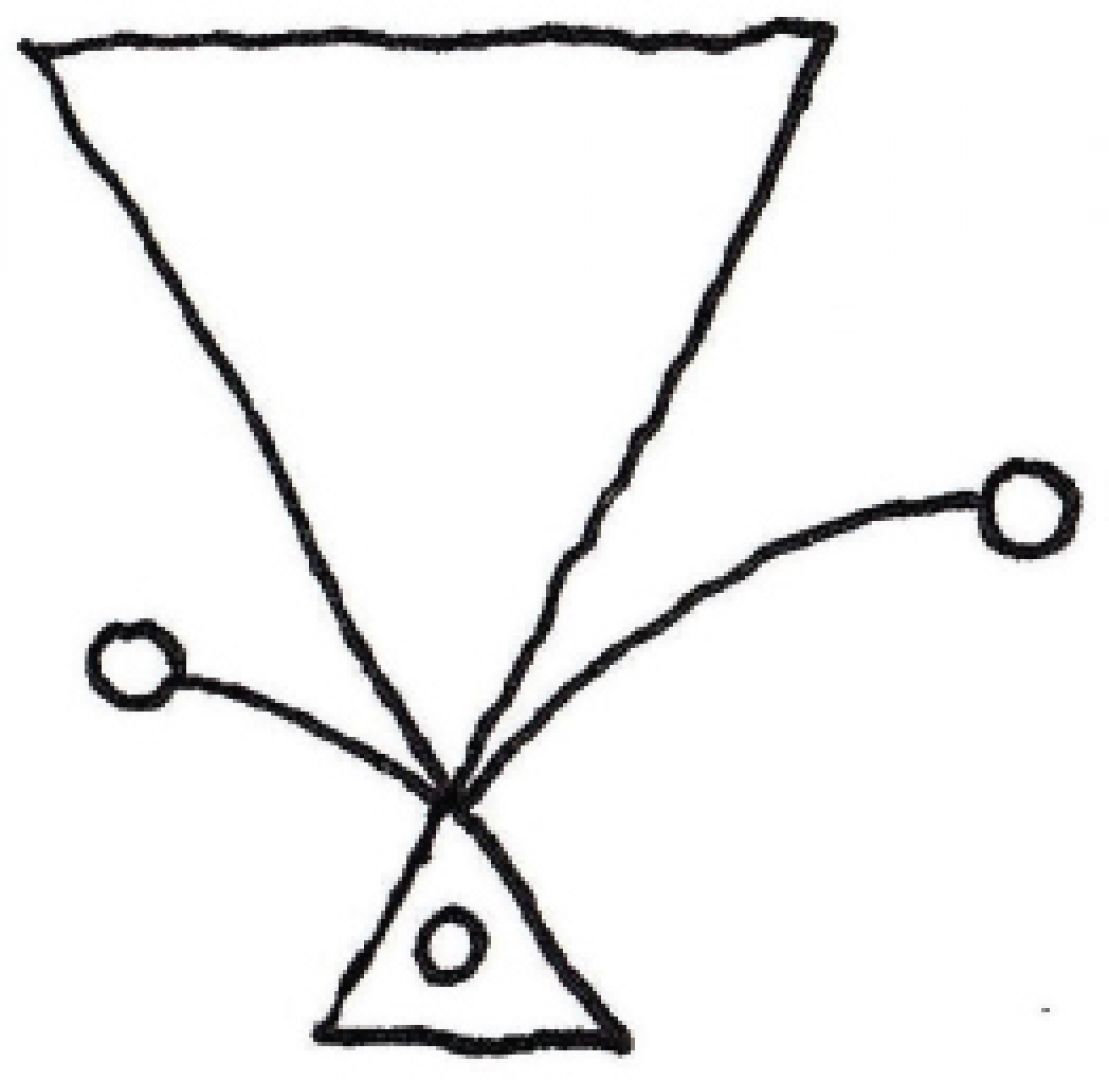

Sometimes, in little hidden places around town, I would see a strange symbol. Once I discovered the symbol, I began to notice it in other places, or different versions of it. I’d happen upon it unexpectedly: it would be carved into a tree, or written in the margin of a textbook, or spray-painted under a bridge, and although there were variations, there were always four parts that looked like a diagram of a flower, or the features of an alien face, or a sketch of some biological system, or something obscene—a kind of big rounded figure above, a smaller similar rounded figure with something inside it below, and, coming out of them on the sides, two arcing pipes of unequal length, both ending with a kind of knob or cap or circle.

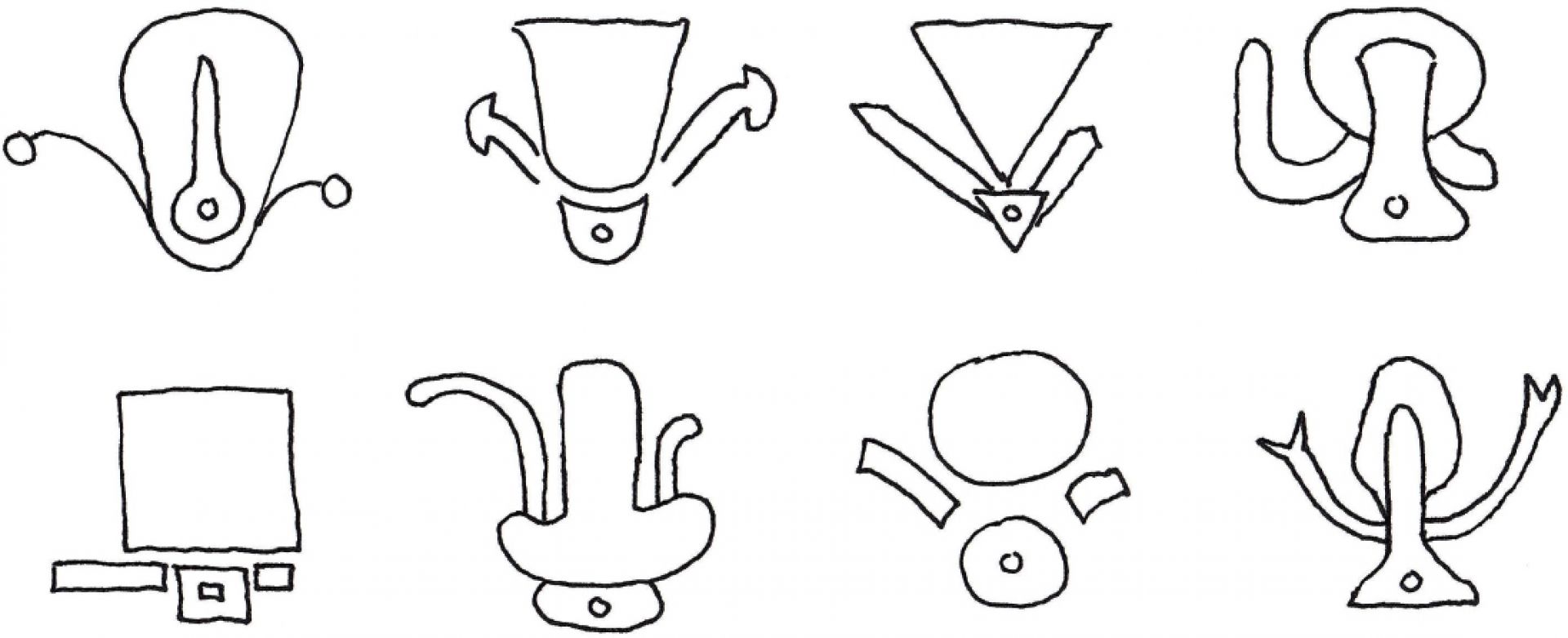

Here are some of the symbols I found around town that I copied into my notebook:

I’d carve it with my pearl-handled knife. As if to tell whoever was putting up these symbols: This is my contribution. I know about this, too. I’m part of your club.

But I didn’t know what it was.

I wasn’t part of any club.

There was an abandoned convenience store out at the edge of town. It still had its cash register and a broken counter and the aisles were empty except for some old magazines lying around, a few dusty dented cans, collapsed racks, empty bottles from the kids who drank here at night, and a tree growing right up out of the side, busting through the roof. There were animals living in the basement, or I thought there were, because sometimes I heard noises coming from down there. But I never went into that basement.

Until a year ago. I was biking past the abandoned store at dusk when I heard a racket coming from inside. A horrible yowling and shrieking.

A shape flashed out of the store, streaking away into the woods.

Then the store was silent.

I didn’t want to go in. But something drew me toward it. I ended up going in, I couldn’t help it, I just wanted to see what had happened. Inside, the store looked pretty much like I remembered it did during the day, only darker, more shadows. I had never ventured in there so late before. I peeked down the basement stairs.

I heard a soft mewling.

I wished it wasn’t so dark. I crept down the stairs anyway, testing each one with my weight in case they were rotten, until I came to the bottom and looked around the dim basement.

Something awful had happened here.

The concrete walls and dirt floors were splattered with guts like a couple of animals had exploded. Blood on the walls. Scraps of fur strewn all around the floor. Tiny organs unraveled and torn. Awful smell.

Something had come in here and killed everything.

I saw a dead mother cat and her litter of dead kittens. One surviving kitten was hiding in a narrow space under a collapsed cabinet, her yellow eyes blinking at me.

I got close and held out my hand. The kitten shied away. I spoke softly, I made the kind of sounds I thought a kitten would like. The kitten just stared. At one point it kind of crept forward, but when I moved my hand slightly toward it, it drew back into its space.

We did this for a long time.

The smell of dead animal all around me was turning my stomach. And it was really getting dark now. So I left the kitten in its hiding place, and went back up the stairs, and got onto my bike.

I heard the little mewling again.

The kitten had followed me out.

After a minute it let me pick it up. I put it in my bike basket and took her home. Mom and Cecilia didn’t like the idea of having a cat. Dad didn’t say much, but the next day he took me to the vet and the kitten got her shots and when the vet asked me her name, I named her after that song Electrifier always played that I never quite understood.

I had Nikki and I loved Nikki, but that was it. After our group of friends broke up, I didn’t have anyone else to hang out with. I didn’t understand what I was doing wrong, why people occasionally made comments about how I dressed, I had always dressed like this. I didn’t understand why I got teased about my hair sometimes, I hadn’t thought of my hair being any other way, it was just my hair.

But I did get it. I had to pick a specific style. I had to start being intentional. Okay, was I an athlete? Uh, no. A preppy? I didn’t look like one and I couldn’t afford the clothes. A skater? Please. A burnout, a princess, a punk, an art freak? Nothing worked. And I didn’t understand why, whenever people did get into a particular group, they began to laugh at things that clearly weren’t funny, why they got excited by things that obviously were boring.

I couldn’t figure out where I fit in. Maybe I had never fit in and I just hadn’t noticed it until recently. If I stayed in this town much longer, I thought, maybe I wouldn’t even fit in with myself.

I wanted out.

I wanted out of our house. Cecilia and I used to have friends over, until our house began to feel dingy compared to their houses. When Dad’s tire shop went out of business everything started to slip. The broken furniture that Dad half-assedly tried to repair, then banished to the basement. The stained carpet that never got cleaned or replaced. Mom and Dad used to talk about college, but even though it was already the spring of Cecilia’s junior year, they weren’t mentioning it so much anymore. Neither was Cecilia.

I wanted out.

Some small part of me said: why not run away?

It would be my own adventure, I thought. The world owed me an adventure. I could even run away for just one summer and come back, if I wanted. That way I wouldn’t even miss school.

It was a stupid idea. Even still, I saved my allowance, hiding the money in a shoebox in my closet, adding to it little by little. Like it was a game to see if I could really save enough for a bus ticket to the city. But the more money piled up in my shoebox, the more real running away felt. My money was getting bigger, stronger. My money had weight. My money was ready to do its job. Where are your guts? said my money.

Maybe I did hate this town. Maybe I did hate my life.

That was the summer I had planned to run away.

But that was the summer of the tornado killer.

I should’ve run.

***

The night of Tornado Day there was supposed to be a small party at Archie’s house.

This party had been planned for a while, actually, just a little dinner thing for Archie and Cecilia and their little group. Archie’s family was moving to Canada in a few weeks so I guessed we’d never see him again. It was supposed to be a kind of going-away party, but it also signaled the end of the popular clique Cecilia had burned her bridges getting into.

But after the tornado destroyed the school, Archie’s party transformed into something bigger. Because school was more than out—school was erased. Summer vacation was already here, even though it was only April. Everyone was shocked and freaked out by what had happened, there had been a lot of tears and emotion, and now people wanted to get together and talk about it, they needed to be together, to see each other. Somewhere along the line Archie or his parents changed the terms of the party. Now it was a big school’s-out bash and everyone was invited.

It was months ago when Archie had first told Cecilia he was moving to Canada. Cecilia had made a big crying scene about it. The two of them had been going out for almost a year, ever since last summer. But even though Cecilia enjoyed the popularity she gained from being with Archie, I sensed she was bored of him. I think she was just impatient for him to move already. Maybe they were both only acting the parts of their stale relationship, waiting for the move to do the work of breaking up for them.

It was already dark when Cecilia and I went to the garage to get our bikes to ride over to Archie’s house for the party, and Cecilia looked at me and said, “No. Please. You’re not bringing that cat to the party.”

I already had Nikki in my bike basket. “Why not?”

“Because people don’t bring their cats to parties, do I really have to explain this?” Cecilia gave me one of her looks. “Especially since that thing still has its claws. It’ll slash up somebody’s face.”

“It’s cruel to declaw a cat.”

“We all get it, you’re the freak who bikes everywhere with headphones on and a cat in your basket. You’ve established that fascinating persona. Take tonight off.”

I just stood there.

“Okay, look.” Cecilia exhaled. “Do you really want everyone at the party to be touching Nikki? Asking to pet her and whatever?”

“Fine, fine.” I put Nikki in the breezeway behind the garage. I didn’t like to do it, though. Neither did Nikki. As soon as the screen door tapped shut, she immediately began meowing.

“She’ll miss me,” I said.

“She’ll stop crying as soon as you leave,” said Cecilia. “Nikki is a master manipulator.”

“Sure.”

“You don’t even know, that kitten has levels,” said Cecilia. “Wheels within wheels on that kitten.”

“And people say I’m the weird one.”

“And ditch those headphones too, okay? You can go a night without your beep-boop music.”

“You’ve never even listened to my music.”

“God, I’ve tried,” said Cecilia. “It sounds like porn music for computers.”

In her freshman year Cecilia had figured out, observing the upperclassmen, that she could get more social power if her jokes were dirtier. She’d say crass stuff to me but then later on, when she was with the group, she’d toss off polished versions of the same lines, as though she’d just come up with them.

“Oh, does it?” I said.

“Yeah, like computers literally getting each other off. Rubbing modems on their floppies.”

“Gross,” I said. “Also, dumb.”

“Your music is like listening to a disk drive jack off,” said Cecilia, enjoying herself. “Spraying zeroes and ones everywhere.”

“There’s a joystick joke somewhere and you’re passing it up.”

“So funny. Let’s go.”

Cecilia’s problem was that she was secretly too wholesome to do those kinds of jokes right. They didn’t come off as dirty, just strange. Cecilia didn’t want to be strange, she wanted to be popular, and in the end she was good at shaving off her awkward edges, she was good enough at pretending.

So Cecilia and I biked over to Archie’s.

It was a beautiful night, it was warm and the dark felt welcoming, you could smell and feel it all around you, wind blowing through the trees, spring sliding into summer, and my bike was flying through it, shooting me forward on pure air. The wind smelled like fresh-cut grass, rushing water, deepening night. I saw Archie’s house just ahead, alone at the top of a hill, its windows throwing out warm yellow squares of light.

I was still buzzing from everything that had happened today. A tornado had destroyed my school. Then I had watched as a strange boy somehow killed the tornado. It already felt like a dream. The rest of the day had been a flurry of panicked parents and reporters trying to interview us and intense phone calls and just seeing each other walking around the neighborhood and saying “Could you believe that?” and “So you’re going to Archie’s, right?” and now summer vacation was suddenly here, astonished at itself, months early, and I felt like anything could happen—Archie’s house might blink its dozens of luminous window-eyes, unfold giant wings, and flap up into the sky. I had fresh skin, new eyes, new ears. I was ready.

I was thinking about the tornado killer.

The way he had looked at me, the moment before the lights went out.

Maybe I’d imagined it. I didn’t know how it made me feel. It wasn’t a pleasant feeling. In fact it didn’t make me feel good at all. The way the tornado killer had looked at me didn’t fit into the world I knew, like how I felt when I read those library books I didn’t understand, or didn’t want to understand.

Cecilia said the tornado killer was “cute.”

Not the word I’d use.

Cecilia’s bike darted in front of me, she cut me off with a whoop and I pumped the pedals to catch up and then we were racing, weaving back and forth, crisscrossing, leaning on our handlebars, laughing. Cecilia pulled ahead, her hair flying out behind like streamers, and we were slicing between cars, whirling down the street, just feeling happy, like we were before she’d started up with Archie.

I hadn’t been to Archie’s house for months.

There was a reason.

I had always known about Archie’s house, but I hadn’t actually been inside it until this past year. I had been curious about it since I was a kid, though, since his house was so much older and bigger and more ornate than every other house in town. Obviously we had trick-or-treated at it, and Archie’s family was famous in town for going all out at Halloween, like putting up over-the-top decorations, and one year even making it so you had to go through a kind of elaborate funhouse tunnel to get to their doorway. But I had never gone inside until Cecilia began going out with Archie. Even though Cecilia put me down, she also looked out for me, in her big-sister way, and maybe to make up for causing me to lose my friends, she eased me into Archie’s clique, like I was somebody, or a somebody-in-training.

Until then Archie’s house had been like school dances, something mysterious I only observed from a distance. Cecilia went to every school dance, I never went. I didn’t have anything against dances in principle, though, and when I once went along with Mom to pick Cecilia up from her winter formal, I saw from our car that her dance was completely different than the awkward eighth-grade dances I despised—it was at a rented hall, not our nasty cafeteria, and from the car I saw silhouettes of people coming out of the colored lights and I heard the distant booming music and the buzz of

laughter and talking, and I thought, okay, sure, this seems glamorous, maybe I want to experience it, and maybe being in Archie’s group would be like that, and give me a way in to that world, even though I knew the others in Archie’s group didn’t care about me. That was fine. I could handle being on the edges of things.

And I loved Archie’s house.

Archie’s house was separate from the neighborhoods where everyone else lived, an elaborate mansion so big and sprawling that parts of it went unheated in the winter, a hundred rambling haunted-feeling rooms, many of them filled with stuff it seemed no one had touched in years.

Last summer, when Archie and Cecilia first started going out, their clique hung out at Archie’s almost every day, with me kind of tagging along, and the scene was clean-cut in a typically Archie way, all of us playing casual games of softball in his huge backyard, and eating apples from his orchard, and watching horror movies late into the night, sleeping over in the maze of attics. Sometimes the boys and girls secretly paired off to make out, often in different combinations, like they were all just sampling each other. But nobody gave me an inviting eye. No hand touched my leg. I kept watching TV and pretended not to notice.

I remember last Fourth of July we shot fireworks off Archie’s roof, special fireworks his dad had bought out of town, fiery green and purple birds that flapped and smoked and shrieked, six-foot-tall robots with flaming eyes that marched in circles and fell apart into sparkling jumbles of melting arms and legs, scarlet rockets that screamed off into the sky and burst so bright and spread across the stars so lush and red that when I looked up, it was as though the whole universe had bloomed into a gigantic rose for me, bleeding across the sky and spreading beyond my eyes, and even though I really didn’t belong at Archie’s, or with this group, nevertheless I felt lucky, at that moment I was right where I wanted to be, alone in the giddy gorgeous center of the universe.

***

Cecilia and I rolled our bikes up Archie’s driveway to the porch. It was already kind of dark. Cecilia rang the doorbell. We could hear shouts and laughter from inside and then Archie’s mother opened the door.

Archie’s mother stared at us in her broken way, like she wasn’t really seeing us. As though she hadn’t actually expected anyone to be there. Always a little smaller than I remembered her. She didn’t move from the doorway at first, just gazing past us, gray and quiet.

I never understood why Archie’s dad had married her. Archie’s dad used to run an engineering company but now that he was retired, he mostly puttered in his barn, building and fixing stuff, a big man with a big mustache, and we all liked him. Sometimes I secretly wished he was my father, instead of my own dad, which was unfair but I couldn’t help it. Archie’s family was just kind of perfect, not in that they acted like they were better than you, but you just felt lucky to be around them, you wanted to be them.

Except for his mother. Nobody in their right mind would want to be her—a nervous, mousy lady with a vaguely pious air, scolding us over things we didn’t understand, but then other times overly friendly and icky sweet. I felt awkward around her. So did Cecilia and I think everyone else, but nobody said anything. We kind of passed over the topic of Archie’s mother in silence, to be polite.

We didn’t really see Archie’s mother that much, actually. She only appeared every once in a while, in the background of a party or a sleepover, hovering around in her meek way and making puzzling comments. The snacks she made always tasted sour and odd. Luckily Archie’s dad did most of the cooking, and while we helped him out in the kitchen chopping up vegetables and laughing and listening to music, Archie’s mother would retreat into the creepier parts of the house and quietly lock herself away.

Those parts of the house weren’t explicitly off-limits. But Archie never took us down those dustier, less-frequented hallways, and we hesitated to pry because it felt like bad manners. Sometimes, though, by accident, I’d come upon certain locked rooms. I’d try the doorknob, I’d knock on the door, and there’d be silence for a moment, and then Archie’s mom’s voice would come, faintly: “I’m in here…” like she was in the bathroom. But I don’t think it was a bathroom. Those rooms always seemed to be locked, even when nobody was inside them.

The last time I was at Archie’s was New Year’s Eve, four months ago, just a few weeks before Archie told us he was moving to Canada. The party was over, we had rung in the new year, auld lang syne and everything, and we were all sleeping over and Cecilia and I had our own room, sharing a bed, when late in the night Cecilia touched my shoulder and whispered to me, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...