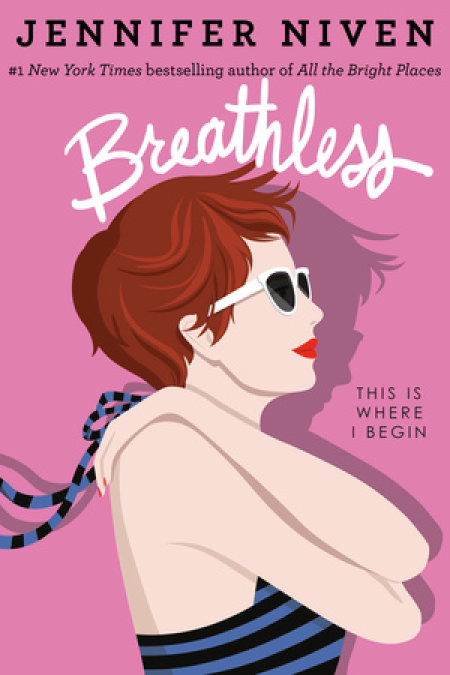

Breathless

Jennifer Niven

8 days till graduation

I open my eyes and I am tangled in the sheets, books upside down on the floor. I know without looking at the time that I’m late. I leap out of bed, one foot still wrapped in the sheet, and land flat on my face. I lie there a minute. Close my eyes. Wonder if I can pretend I’ve fainted and convince Mom to let me blow off today and stay home.

It’s peaceful on the floor.

But it also smells a bit. I open an eye and there’s something ground into the rug. One of Dandelion’s cat treats, maybe. I turn my head to the other side and it’s better over here, but then from outside I hear a horn blast, and this is my dad.

So now I’m up and on my feet because he will just keep honking and honking the stupid horn until I’m in the car. I can’t find one of my books and one of my shoes, and my hair is wrong and my outfit is wrong, and basically I am wrong in my own skin. I should have been born French. If I were French, everything would be right. I would be chic and cool and ride a bike to school, one with a basket. I would be able to ride a bike in the first place. If I were living in Paris instead of Mary Grove, Ohio, these flats would look better with this skirt, my hair would be less orange red--the color of an heirloom tomato--and I would somehow make more sense.

I scramble into my parents’ room dressed in my skirt and bikini top, the black one I bought with Saz last month, the one I plan to live in this summer. All my bras are in the wash. My mom’s closet is neat and tidy, but lacking the order of my dad’s, which is all black, gray, navy, everything organized by color because he’s colorblind and this way he doesn’t have to ask all the time, “Is this green or brown?” I rummage through the shelf above and then his dresser drawers, searching for the shirt I want: vintage 1993 Nirvana. I am always stealing this shirt and he is always stealing it back, but now it’s nowhere.

I stand in the doorway and shout down the hall, toward the stairs, toward my mom. “Where’s Dad’s Nirvana shirt?” I’ve decided that this and only this is the thing I want to wear today.

I wait two, three, four, five seconds, and my only answer is another blast of the horn. I run to my room and grab the first shirt I see and throw it on, even though I haven’t worn it to school since freshman year. Miss Piggy with sparkles.

At the front door, my mom says, “I’ll come get you if Saz can’t bring you home.” My mom is a busy, well-known writer--historical novels, nonfiction, anything to do with history--but she always has time for me. When we moved into this house, we turned the guest room into her office and my dad spent two days building floor-to-ceiling bookcases to hold her hundreds of research books.

Something must show on my face because she rests her hands on my shoulders and goes, “Hey. It’s going to be okay.” And she means my best friend, Suzanne Bakshi (better known as Saz), and me, that we’ll always be friends in spite of graduation and college and all the life to come. I feel some of her calm, bright energy settling itself, like a bird in a tree, onto my shoulders, melting down my arms, into my limbs, into my blood. This is one of the many things my mom does best. She makes everyone feel better.

In the car, my dad is wearing his Radiohead T-shirt under a suit jacket, which means the Nirvana shirt is in the wash. I make a mental note to snag it when I get home so I can wear it to the party tonight.

For the first three or four minutes, we don’t talk, but this is also normal. Unlike my mom, my dad and I are not morning people, and on the drive to school we like to maintain what he calls “companionable silence,” something Saz refuses to respect, which is why I don’t ride with her.

I stare out the window at the low black clouds that are gathering like mourners in the direction of the college, where my dad works as an administrator. It’s not supposed to rain, but it looks like rain, and it makes me worry for Trent Dugan’s party. My weekends are usually spent with Saz, driving around town, searching for something to do, but this one is going to be different. Last official party of senior year and all.

My dad sails past the high school, over Main Street Bridge, into downtown Mary Grove, which is approximately ten blocks of stores lining the bricked-paved streets, better known as the Promenade. He roars to a stop at the westernmost corner, where the street gives way to cobbled brick and fountains. He gets out and jogs into the Joy Ann Cake Shop while I text Saz a photo of the sign over the door. Who’s your favorite person?

In a second she replies: You are.

Two minutes later my dad is jogging back to the car, arms raised overhead in some sort of ridiculous victory dance, white paper bag in one hand. He gets in, slams the door, and tosses me the bag filled with our usual--one chocolate cupcake for Saz and a pound of thumbprint cookies for Dad and me, which we devour on the way to the high school. Our secret morning ritual since I was twelve.

As I eat, I stare at the cloudy, cloudy sky. “It might rain.”

My dad says, “It won’t rain,” like he once said, “He won’t hit you,” about Damian Green, who threatened to punch me in the mouth in third grade because I wouldn’t let him cheat off me. He won’t hit you, which implied that if necessary my dad would come over to the school and punch Damian himself, because no one was going to mess with his daughter, not even an eight-year-old boy.

“It might,” I say, just so I can hear it again, the protectiveness in his voice. It’s a protectiveness that reminds me of being five, six, seven, back when I rode everywhere on his shoulders.

He says, “It won’t.”

In first-period creative writing, my teacher, Mr. Russo, keeps me after class to say, “If you really want to write, and I believe you do, you’re going to have to put it all out there so that we can feel what you feel. You always seem to be holding back, Claudine.”

He says some good things too, but this will be what I remember--that he doesn’t think I can feel. It’s funny how the bad things stay with you and the good things sometimes get lost. I leave his classroom and tell myself he doesn’t begin to know me or what I can do. He doesn’t know that I’m already working on my first novel and that I’m going to be a famous writer one day, that my mom has let me help her with research projects since I was ten, the same year I started writing stories. He doesn’t know that I actually do put myself out there.

On my way to third period, Shane Waller, the boy I’ve been seeing for almost two months, corners me at my locker and says, “Should I pick you up for Trent’s party?”

Shane smells good and can be funny when he puts his mind to it, which--along with my raging hormones--are the main reasons I’m with him. I say, “I’m going with Saz. But I’ll see you there.” Which is fine with Shane, because ever since I was fifteen, my dad has notoriously made all my dates wait outside, even in the dead of Ohio winter. This is because he was once a teenage boy and knows what they’re thinking. And because he likes to make sure they know he knows exactly what they’re thinking.

Shane says, “See you there, babe.” And then, to prove to myself and Mr. Russo and everyone else at Mary Grove High that I am an actual living, feeling person, I do something I never do--I kiss him, right there in the school hallway.

When we break apart, he leans in and I feel his breath in my ear. “I can’t wait.” And I know he thinks--hopes--we’re going to have sex. The same way he’s been hoping for the past two months that I’ll finally decide my days of being a virgin are over and “give it up to him.” (His words, not mine. As if somehow my virginity belongs to him.)

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved