- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

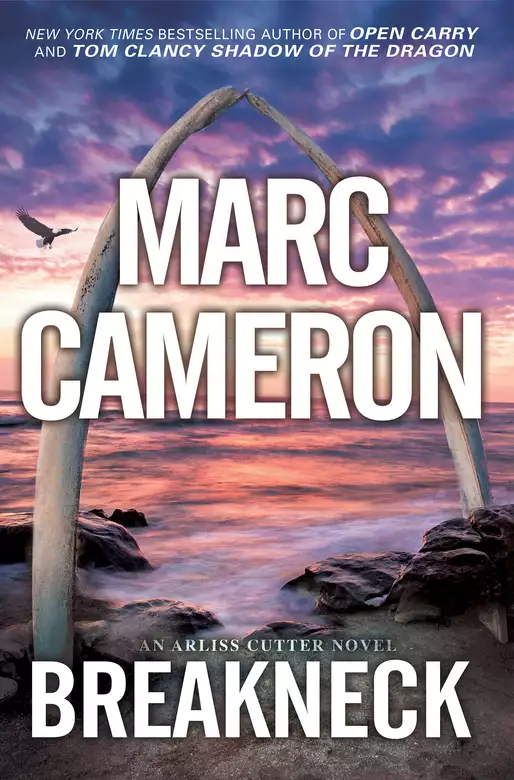

Synopsis

A train ride into the Alaskan wilderness turns into a harrowing fight for survival for Deputy US Marshal Arliss Cutter and a mother and daughter marked for death …

Off the northeast coast of Russia, the captain and crew of a small crabbing vessel are brutally murdered by members of Bratva, the Russian mafia—their bodies stuffed into crab pots and thrown overboard. The killers scuttle the vessel off the coast of Alaska and slip ashore.

In Washington, DC, Supreme Court Justice Charlotte Morehouse prepares for a trip to Alaska, unaware that a killer is waiting to take his revenge—by livestreaming her death to the world.

In Anchorage, Alaska, Deputy US Marshals Arliss Cutter and Lola Teariki are assigned to security detail at a judicial conference in Fairbanks. Lola is tasked with guarding Justice Townsend’s teenaged daughter while Cutter provides counter-surveillance. It’s a simple, routine assignment—until the mother and daughter

decide to explore the Alaskan wilderness on the famous Glacier Discovery train. Hiding onboard are the Chechen terrorists, who launch a surprise attack. While they seize control of the engine, Cutter manages to escape with Justice Townsend by jumping off the moving train—and into the unforgiving wilderness.

With no supplies and no connection to the outside world, Cutter and the judge must cross a treacherous terrain to stay alive. Two of the terrorists are close behind. The others are on the train with the judge’s daughter—and they plan to execute her on camera. With so many lives at stake, Cutter knows there are

only two options left: catch the train and kill them all … or all will be killed.

Release date: April 25, 2023

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Breakneck

Marc Cameron

Six-three, with a healthy fighting weight of 240 pounds, Cutter took up most of the real estate in the bow. One of three in the boat, he was dressed for the bush—wool shirt, which was black-and-green plaid, brown Fjällräven pants, and rubber XtraTuf boots. He’d taken off his desert tan boonie hat and clipped it to his pack, revealing a thick mop of unruly blond hair. It wasn’t that he was averse to combing it. The thought just rarely occurred to him.

A twelve-gauge Remington 870 with a bird’s-head grip and a remarkably maneuverable eleven-inch barrel—called a WitSec shotgun in the Marshals Service—rested in a scabbard secured to the waterproof daypack at his feet.

Cutter’s partner, a twentysomething Polynesian deputy named Lola Teariki, hunkered amidships, trying in vain to smash a biting moose fly that buzzed around her face. George Polty, a Village Public Safety officer, sat on an overturned plastic bucket working tiller on the outboard, torn between chuckling at Lola’s antics and watching out for sandbars.

Cutter scanned the wood line, wondering if their target was in the shadows, watching.

Forty-two-year-old Lamar Wayne Jacobi was wanted on a federal warrant for mail fraud, a relatively innocuous white-collar crime, but a history of a violent assault on his ex-wife put the deputies on guard. The Oregon judge who’d presided over the assault case eight months earlier hadn’t viewed smacking someone in the shoulder with a ball-peen hammer as bad enough to hold Jacobi in custody pending trial. The judge had ruled that if the accused had wanted to kill the victim, he would have struck her in the head. Apparently, it never occurred to His Honor that the defendant might simply have missed his ex-wife’s noggin during the attack.

Cutter had long since given up on trying to make sense of judicial fiat, focusing instead on recapturing the pukes that courts insisted on releasing back on the street. Those releases occurred with slightly less frequency in federal court, but they still happened enough that Cutter and his team had, as they say, a target-rich environment.

Jacobi legged it the same day he made bond for the hammer assault, precisely one month before a federal grand jury in Dallas indicted him for defrauding two elderly women out of their life savings with a roofing scam. Local law enforcement didn’t have the resources to spend much time chasing fugitive con artists, and they were all too happy to pass the case to the United States Marshals Service, once federal paper was involved. Deputies from both the North Texas Fugitive Task Force and Pacific Northwest Violent Offenders Task Force worked the case. Jacobi moved around the country like a Whac-A-Mole popping up all over the place. Other than some flimsy intel that he’d fled to Alaska, there wasn’t much to go on. The case literally fell farther and farther down the stack, beneath sexier, more pressing warrants that landed every day. It would have languished for months, had a Yupik duck hunter not posted on YouTube footage of his trip along a tributary of the Yukon River and shots of a mysterious white man. Even then, with over 800 million videos on the platform, seven seconds of GoPro footage would have gone unpursued, but for the fact that Jacobi was wanted as a material witness in the murder of a prominent Texas state legislator. A Dallas County DA investigator, aware of the slim possibility that Jacobi might be in Alaska—and interested in duck hunting, anyway—stumbled on the YouTube footage during a lunch break. The image was distant and only lasted a few seconds, but facial recognition software put the odds at better than 75 percent that it was Jacobi.

The district attorney was up for reelection, and with a high-profile murder trial looming, his office made a formal request for the US Marshals Service to turn up the heat on Jacobi’s fugitive case.

As it turned out, an upcoming election, not trying to clobber your ex-wife with a ball-peen hammer, provided the best grease for the wheels of justice. The chief deputy US marshal for the Northern District of Texas reached out to District of Alaska Chief Jill Phillips—and Lamar Wayne Jacobi’s powder-blue warrant folder shot to the top of Arliss Cutter’s stack.

Eighteen hours after Chief Phillips received the collateral request, Cutter and Teariki found themselves climbing out of a thirty-seat Ravn Air Dash 8 in the Yupik village of St. Mary’s—over four hundred miles from the road system. Two hours later, they were in VPSO George Polty’s boat, motoring up the Andreafsky.

The Alaska State Trooper lieutenant in Bethel had tasked the two troopers stationed in St. Mary’s to assist, but as usual, they were up to their eyeballs in work when the deputies arrived. This time it was a death investigation involving an ATV driver and a utility pole. Cutter and Teariki found themselves in the capable, if unarmed, hands of a Village Public Safety officer who would be their boat driver and guide. VPSOs had powers of arrest, but most carried no sidearm, relying instead on a Taser, pepper spray, and their wits. George Polty had grown up sixty miles down the Yukon River in the village of Alakanuk—which he pronounced with a clicky wet throat that sounded very much like the cry of a raven and reinforced to Cutter that he would never come close to learning the language.

The troopers assured Cutter they’d be right along if nothing else popped up. That meant the deputies and Polty were on their own. In bush Alaska, something always popped up.

The thirty-horse Tohatsu outboard pushed the skiff up the river at a respectable pace. Runoff from melting ice and snow put the Yukon at flood stage, giving them a backward current of almost two miles an hour when they’d left St. Mary’s. Even now, some fifteen miles upstream, turbid water eddied and swirled as if it didn’t quite know which way to flow.

Perched in the center of the skiff, Lola Teariki knocked a thick strand of ebony hair out of her customary high bun as she swatted at the moose flies. It now trailed across her cheek, pasted there by periodic rain. Five years as a deputy US marshal added to her natural swagger and ability to turn her Polynesian princess face into a fearsome scowl—which she now used to little effect on the moose flies.

George Polty took a small metal tin from the pocket of his exterior ballistic vest and offered it to Teariki.

“Yarrow salve,” he said. “Helps keep the bugs away.”

A chilly rain pocked the surface of the river, hard enough to make a jacket necessary but not enough to chase away the clouds of mosquitoes and no-see-ums.

Lola waved her hand through the morphing cloud. “Yarrow? Like the weed?” Willing to try anything, she leaned in and took it.

“Don’t work quite as good as DEET,” Polty said. “Smells better, though. I save the DEET for when the bugs are really bad.”

Lola grimaced. “You don’t call this really bad?”

“Nah,” Polty said. “Bad is when you’re camping and the inside of your tent looks like fur ’cause so many mosquito noses are poking through the net tryin’ to get at you—”

His head suddenly snapped toward the tree line.

Cutter followed his gaze.

Polty crinkled his nose—an unspoken “no” in Yupik culture—and then translated by shaking his head for Cutter’s benefit.

“I don’t see anything,” the VPSO said. “But I can feel it lookin’ at me.”

Lola cursed at the bugs, slapping her own face while she scanned the wood line. “A bear, maybe,” she said. “Aren’t the salmon beginning to run?” Another swat knocked more hair out of her bun. “This is so stuffed . . .”

Polty gave a somber nod. “Could be a bear, I guess, but I don’t think they’re too thick yet. Fish been comin’ in later and later the last couple of years, if they come at all.”

The two moose flies circled Teariki’s head like biplanes buzzing King Kong. One got through her defenses and zapped her on the upper lip, incising a tiny hunk of flesh before she could react. Like their southern horsefly cousins, moose flies were resilient little beasts, capable of withstanding a solid flat-handed swat and still coming back for more.

Lola killed one, grimacing at the movement of a recently cracked rib. She flicked her non–gun hand to keep the remaining fly at bay.

“Talk to me, Cutter. What are you thinking?” Of Cook Island Maori descent, her Kiwi accent tended to clip her Rs, making “Cutter” sound like “Cuttah.”

“Just a feeling,” he said.

Polty stretched his arm over the water. “This part of the river is bad news. Not good . . . not good at all.” He shot a quick glance at Cutter, then Lola, eyes wide. “You guys ever been to Hooper Bay?”

“A couple of years ago,” Lola said. “Why?”

Cutter shook his head. At one fifth the size of the contiguous United States, there was still a lot of Alaska he’d yet to visit.

“A girl died in the school,” he said. “Ukka tamani . . . long, long ago . . .”

“How’d she die?” Lola asked.

“I’m not even sure,” Polty said. “But it must have been brutal. People see her ghost hangin’ around all the time.”

Lola gave him a side-eye. “What do you mean all the time?”

“That’s pretty much it,” the VPSO said, earnest as a church deacon. “They see her all around the school—library, halls, peeking out the windows—teachers, students, lots of folks.”

“Okay,” Cutter said. “Hooper Bay’s, what, a hundred miles away? What’s that got to—”

Polty jammed his index finger at the aluminum siderail, shaking his head as if his reasoning was all so obvious. “This stretch of river killed little Winnie Tomaganak.” He shivered, checked the tree line again, and then wiped a hand over the top of his head to steady his nerves. “She disappeared just a week ago. Poof. Vanished off the bank. We searched every snag and sandbar.” He stared over the side of the boat into the water, eyes glazed. “You ever see the big treble hooks they use to drag the water for a body?”

Cutter nodded.

“Horrible thing, draggin’ a river,” Polty said over the roaring motor. “Hoping you find something . . . then hoping you don’t . . . I’ll tell you that much.” His index finger went back to poking the gunnel, punctuating his words. “We looked for that poor kid for three days solid. River ice musta taken her out to sea. It can sneak up and eat you alive if you’re not lookin’.”

Lola finally nabbed the surviving moose fly and flicked it into the water. A fat grayling rose from the depths and gulped it down with a burbling splash.

“You’re telling me you feel the ghost of a dead child watching you from the woods? I’m a good Christian girl. I don’t believe in that shit.”

The way she eyed the bank said she obviously did.

“That’s a tragic story,” Cutter said, meaning it. “But no. I don’t think there’s a ghost in the woods.”

Polty shrugged. “Something’s out there, Marshal. Winnie’s body wasn’t ever found. A bad death like that, I bet her little spirit is just wanderin’ the banks, trying to find a door to the other side—”

Lola banged her fist on the gunnel and made a futile attempt at chasing away the cloud of mosquitoes with the other.

“How about some speed, George? Get us away from these mozzies. And knock off this shittery about ghosts. You’re creepin’ the hell outta me.”

Polty grunted, giving a little shrug like he knew better, and then rolled on more throttle. The added speed did little good. Mosquitoes and tiny biting midges the locals called “no-seem-ums” followed the boat in great black clouds, pulsing and morphing like specters on unseen currents of chilly air.

Lola slapped herself on the neck. “That footage that’s supposed to be Jacobi,” she yelled above the sound of chattering water. “Where was that taken?”

“A half mile upriver,” Polty shouted back. “Near as I can tell, he was fishing.” He hooked a thumb toward the bank and then caught his ballcap before it blew off. “There’s a derelict camp in the woods not far from here.”

Lola dabbed at the fly bite on her lip. “What sort of camp?”

“A bunch of end-of-days whack jobs followed their prophet out here in the late nineties.” Polty let up on the gas, slowing a hair so they could hear each other better. “Ten or twelve of ’em pretty much invaded, preppin’ for the shit to hit the fan on Y2K. This is all Native corporation land, so they had to have some connection. I think one of the main dude’s disciples was half Yupik. The place was a going concern for a while, chickens, greenhouses, some goats, a commune, if you want to call it that. Folks from St. Mary’s would trade for fresh eggs and such—”

“What happened?” Lola asked.

“Not a damned thing,” Polty said. “The earth kept spinnin’ on Y2K plus one. I guess the prophet got sick of the bugs and went back to his dental practice in Chicago. The entire group evaporated as quick as they’d come.”

“But they left the cabins intact?” Cutter mused, waving away a fly.

“Yep,” Polty said. “Good place to spend the winter if you’re running from the law. Kids used to go out there, but everybody says it’s haunted now.”

“Jacobi’s file says he’s spent plenty of time in the woods,” Cutter pondered. “He’s enough of an outdoorsman to survive if push came to shove.”

“Hmmm,” Polty said. “This is a push-comes-to-shove kind of place.”

“You got that right,” Lola said, more relaxed now that she’d dispatched the moose flies and only had to deal with 2 million other biting bugs. “I’ll bet ninety percent of my Academy classmates are sitting in court right now or serving civil papers—” She froze, eyes locked on the far bank some seventy-five yards upriver on the left.

“What have you got?” Cutter whispered.

Lola shot him a glance, turned back to the bank. “You didn’t see that?”

“Jacobi?”

“No,” she said, still peering at the trees. “A Native girl.”

The VPSO smacked the side of his boat. “I told you!”

“It wasn’t a ghost,” Lola said.

“A kid from one of the fish camps, maybe,” Cutter mused.

Polty shook his head. “Nobody’s out at fish camp yet. What’d she look like? This Native girl?”

“Young,” Lola said. “Dark hair, ten, twelve years old.”

“Purple hoodie?”

Lola nodded. “I thought you didn’t see her.”

“I didn’t,” Polty said. “Winnie Tomaganak was wearin’ a purple hoodie when the river got her.”

Cutter shrugged on his daypack, while Polty gunned the throttle, coaxing the little boat up on step.

“Get on the sat phone,” he shouted to Lola. “Let the Troopers know where we are and what we’ve got.”

Lola wedged herself beside the rail and unfolded the satellite phone’s antenna. She plugged one ear with her free hand while she spoke. All the while, she stared so hard at the trees, Cutter imagined they might burst into flames. He liked that kind of focus. It reminded him of himself.

Polty threw the outboard into reverse as he neared the bank, slowing. The bow scraped bottom at the same moment Lola ended her phone call.

“Troopers are an hour and a half out,” Lola said, hushing her voice in the abrupt absence of the deafening outboard. “They want George to stay with the boat.”

“Screw that!” Polty said. He’d gotten past the idea that Lola had seen a ghost. “I was the one who had to look Gladys Tomaganak in the eye and tell her we were callin’ off the search for her daughter. No way I’m waitin’ by the damned boat.”

“No worries, George.” She gave him a wink. “I told ‘em we needed you as a guide.” M4 carbine in hand, she nodded to Cutter, letting him know she was ready. One of the first things he’d taught her was that a sidearm was for emergencies. If chances were good there might actually be a gunfight, you took a long gun. That went double in the bush, miles or even days from any backup.

Cutter jumped out of the boat first, tying the bow line to the base of a stout spruce, while Lola covered the woods, rifle at the ready. The VPSO took a quick moment to detach the black rubber fuel hose that connected the outboard to the plastic tank and hid it behind a clump of willows. The last thing they wanted was to be stranded by someone who decided to borrow their skiff.

The muddy ground along the bank was a perfect track-trap. He found the girl’s trail almost immediately and followed it into the trees. Twenty feet inside the forest, he paused, stooping low to study the tracks more closely. Lola provided overwatch, scanning the shadows, rifle up to her shoulder. The muzzle went where she looked.

Rain began to fall in earnest, pattering the carpet of dead leaves that littered the forest floor.

“Talk to me, boss.” Lola kept her voice low. She chanced a quick glance at the ground, then got back on the rifle. “Whatcha got?”

“New set of tracks,” Cutter said. “Large. Over top of the girl’s.”

“Over top? That means . . .”

“Yep. He’s behind her.” Cutter stood. “Did she make eye contact with you?”

“I don’t think so,” Lola said. “Looked as though she might have heard the boat and was coming out to wave us down. She was turned sideways, though, looking into the trees. You think she’s running from Jacobi?”

“She’s running from someone.” Cutter nodded at the tracks. “If this is Jacobi, then . . .”

Lola glanced over her shoulder at the VPSO. “Our guy’s got no history of resisting arrest, but he’s obviously dangerous, and he doesn’t want to be found. I’m a little concerned about you being out here with no gun if things go sideways.”

“Don’t you worry about me,” Polty said. “I’ll be fine.”

Cutter wiped the rain off his face. “I have an extra pistol if it comes to that.”

He carried his grandfather’s Colt Python, as well as a small Glock 27. The .357 Magnum made more sense in the bush, but the Glock kept him in line with Marshals Service firearms policy. He gave the trees ahead a nod. “The abandoned Y2K camp is through here?”

Polty looked around, then back toward the river, getting his bearings. “We passed it already, maybe a half mile back from where we first saw the girl.”

The three fell into a plodding rhythm. Cutter worked the ground, while Lola and Polty served, respectively, as overwatch and rear guard. There was a strong possibility that they weren’t dealing with a lone fugitive. If it was Jacobi, someone had to have dropped him off and brought him supplies. As this was all Native corporation land, Cutter guessed that someone might even live nearby.

Individual tracks became harder to discern the farther they got from the river. Birch and poplar leaves carpeted the spongy ground. Mottled and slimy with rot, they’d spent the past winter under several feet of snow and now let off the sickly-sweet odor of decay. Here and there, patches of ground had obviously been turned from a traveling foot, but it was often difficult to tell if the creature that foot belonged to had two legs or four. The girl’s movements zigged and zagged, cutting around trees, even backtracking a few times to start off in an entirely new direction. The way the ground was kicked up suggested that she was running most of the time—as was the man behind her.

A stream, some three feet wide, crossed their path a hundred yards in from the river, providing a natural funnel, as well as a few yards of mud for more distinct tracks. Mostly moose and wolf, but human tracks too. Water flowed into the impressions as Cutter studied them, indicating that they’d only recently been made.

He hopped over the stream, taking care not to disturb any tracks or slip in the snotty leaves, then stopped to read the ground on the other side.

Lola cleared the water with an easy leap and came up behind him. “What is it?” A cloud of vapor blossomed from her lips on the chilly air. A raindrop hung from the tip of her nose.

Cutter pointed to a clear line of the larger set of prints that were relatively free of leaves and forest litter. “His left foot pivots slightly and leans in . . . here . . .”

“Checking over his shoulder?” Lola offered.

“That’s right,” Cutter said. “But look. He takes two more steps and—”

“The tracks turn,” Lola said, cutting him off. “He spun around completely and walked backward a couple of strides.” She glanced ahead and then checked the tracks again. “You think he has a rifle.”

“That’s my guess,” Cutter said.

Lola quickly explained their exchange to a puzzled George Polty. “Ever notice how when you look behind you when you’re carrying a long gun, you almost always turn all the way around and walk backward for a step or two, as opposed to just glancing over your shoulder, like you do when you’re unarmed?”

The VPSO mulled it over. “I never thought about it. But I guess that’s true. You want the gun to go where you’re looking.”

Cutter was already moving again, bounding quickly to the next visible track, confirming he was on the right line, then repeating the process. If this girl was on the run, he wanted to close the distance before Jacobi caught up with her.

Lola trotted behind him. “So our guy has a gun and knows he’s being followed. He can’t be that far . . .” She paused, hissing to get Cutter’s attention. “Smell that?”

Cutter took a deep breath, then pointed the same direction the tracks were going. “Woodsmoke. Wind’s in our faces, so—”

A hoarse voice from the shadows to the left caused Cutter to freeze. He resisted the urge to raise the short shotgun, not wanting to escalate the situation into something worse than it was—which was already bad enough. He had no target—yet.

“Damn right the wind is in your face,” the voice said, rough, like rusted barbed wire—or someone who rarely spoke. “While you focus on a whiff of woodsmoke, I creep up from downwind—”

“And?” Teariki’s Kiwi accent came through, making it sound like “ind.”

“What . . . what do you mean?” the voice asked, more than a little bewildered at the sudden challenge. He sounded too old to be their fugitive.

“What do you mean?” Lola asked. “You creep up from downwind and do what? What is your plan exactly?”

The voice mumbled, “Don’t you worry about my plan. I’m telling you now, leave that little girl alone.”

“We need to talk to a man named Jacobi,” Cutter said. “But if it’s the missing Tomaganak girl you’re talking about—”

“So, you’re not friends with that bald guy?”

“Bald guy?” Lola said.

“The one chasin’ the kid.”

“We are not,” Cutter said, gritting his teeth. “Listen—”

“You troopers?” the voice demanded, growing more agitated by the moment.

“US Marshals,” Cutter said.

“You looking for me?”

“Your name Jacobi?”

“It is not.”

“Then we are not,” Cutter said. “Now knock it off and show yourself! I’ve got no time for this.”

Pattering rain and the distant churning of the river made it impossible to pinpoint where the voice was coming from.

“Put your weapons on the ground,” the voice said.

“Yeah.” Cutter shook his head. “We’re not doing that.” He turned slowly to peer into the dense foliage. Nothing.

“What’s your name?” Lola asked, friendly, like they’d just met on the trail.

“Capt . . . Tom . . . Tom Walker . . .”

“Hey,” Polty said. “I’ve heard of you!” He turned to Cutter. “Captain Walker was a soldier at Fort Wainwright. Came out here and disappeared into the woods.” He turned and addressed the bushes. “People said you died a couple of winters ago—”

“They were mistaken—”

“Listen up, Tom,” Cutter said. “We have a child in trouble. Get out here and tell us what you know. If you’ve got a weapon, don’t point it our way.”

The brush rustled a scant fifteen yards to Cutter’s ten o’clock. A gaunt man wearing faded Carhartt coveralls and a backward ballcap stepped out of the scrub. The rifle clutched in his hands looked like an ancient military Mauser—the kind the Spanish used against the Rough Riders from the San Juan Heights. Cutter had taken fire from more than one such rifle in Afghanistan, and knew from experience that the old ones were plenty deadly. He guessed Tom Walker to be in his early fifties, but his eyes shone with a fierce intensity that made him seem younger than he probably was. Living rough had weathered his bronze skin, giving it the shiny, varnished look common to those exposed to long hours of wind. A flyaway gray beard stuck out in all directions, like he didn’t own a mirror or didn’t give a damn. He clutched the rifle down by his thigh, forward of the action, his finger well away from the trigger. Even so, Cutter gestured with the shorty shotgun, hurrying things along.

“Set your gun on the ground.”

“Why? I’m not your guy. The VPSO just told you he’s heard of me.”

“He’s right,” Polty said. “Captain Tom Walker’s kinda famous in this area. We can trust him.”

“I’m not in the trusting business.” Cutter kept his voice low. He stood completely still. “Put down the rifle. Do it now.”

The man complied. Lola moved in and cleared it, popping out the rounds and shoving them in the pocket of her rain jacket. The chamber had been empty, a good sign. She brought the rifle with her when she rejoined Cutter, and then leaned it against a tree behind them, before turning to watch the woods behind them.

“Captain?” Cutter gave a curt nod. He wanted to get moving, but had to deal with one problem at a time.

Walker gave a groaning nod. “14th Cav scout. 172nd SBCT.”

“Ranger Regiment,” Cutter said, introducing himself as he eyed the man. “I did a fair amount of work with cavalry scouts in Afghanistan.”

“Iraq,” Walker said, leaving it at that.

“When?”

“Oh-five through oh-six.”

Cutter knew the 172nd had seen a year-and-a-half deployment in 2005 through 2006, with twenty-six killed in action and over three hundred wounded.

He changed the subject. “You described the man who came through here as bald. What else?”

Walker shrugged. “Heavy, especially for living out here as long as he has.”

Cutter and Lola exchanged a glance.

“Maybe Jacobi shaved his head,” she said.

“How tall would you say he is?” Cutter asked.

“Shorter than me,” Walker said. “A few inches shy of six feet.”

“That’s not Jacobi,” Lola said.

“Where would the girl have gone?” Cutter asked. “Since she was running.”

Walker slumped. “He’s already got her. I assumed you were friends of his.”

“Let’s go,” Lola fumed through clenched teeth. “I don’t give a shit who he is.”

“Agreed.” Cutter scanned the ground, a familiar worry roiling his gut. He looked up at Walker. “Did this bald guy see you?”

“No. He grabbed the kid and just kept going. Dragged her into the trees. I was about to challenge him, when I heard y’all coming up the trail. He either didn’t care that you were behind him or didn’t realize it. I thought I could . . . Anyway, it seemed smarter to stay hidden and work out a plan to save her than get myself shot and leave her to that guy.”

“Which way did he take her?”

Walker pointed south. “Toward his camp. An old compound.”

“The Y2K cabins,” Polty said.

“That’s right,” Walker said. “I used it as a winter place for years, until the new guy turned up last fall and claimed it. He’s bad news, that one. Hangs monofilament with fishhooks around his compound. Son of a bitch nearly blinded me.”

Cutter rubbed the rain out of his face with a forearm and studied the ground again, letting it tell him as much of the story as possible as he came up with the bones of a plan.

“You ever see him with a gun?”

“First time I saw him at all was today,” Walker said. “And yeah, he has a rifle. I’ve heard him shooting it for a couple of months. A big bore from the sounds of it. None of my business. I leave people alone. They leave me alone.”

Cutter searched the trail until he found a clear impression of one of the larger tracks. He stooped beside it, leaving Lola and the VPSO to watch Walker.

“I don’t get it,” Lola said. “This guy’s been around for months, and you’ve never made contact with him?”

Walker gave a resigned shake of his head. “I left Fairbanks to be by myself. Got no use for people—less so for those who try to gouge my eyes out with fishhooks.”

“But you’ve seen the girl before today?” Lola asked.

“She stole some of my supplies a couple of days ago. I tried to talk to her—”

Polty looked as though he’d been slapped. “There were search parties banging up and down this river. You didn’t think to flag down a boat. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...