- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

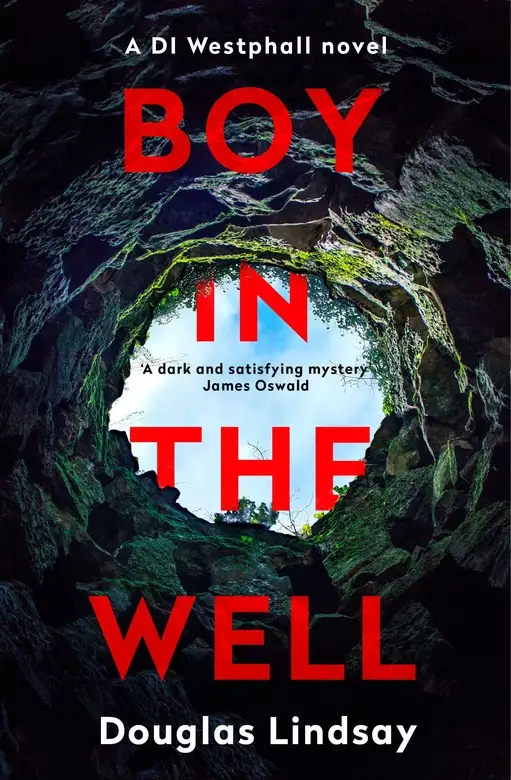

Book 2 in the DI Westphall series.

The body of a young boy is discovered at the bottom of a well that has been sealed for 200 years.

Yet the corpse is only days old....

Soon, similarities from an old crime emerge, and DI Ben Westphall must look to the past to piece together the dark and twisted events taking place in the present.

Release date: May 30, 2019

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Boy in the Well

Douglas Lindsay

Alarm. Eyes open. First look at the morning. Reach out and silence the noise.

Ten-minute snooze set, but I won’t need it. Lie in the grey light of dawn, staring at the ceiling, and right away it’s there. Depression.

No particular reason. Just one of those things that comes with the day. Any given day. Like one of those old blues songs. Woke up this morning . . . In my case, however, I don’t tick any of the old blues men’s boxes. No woman putting me down, no trouble with the law, no drink, no drugs, no long, lonely journeys on the railroad.

There was a time there, for a few years even, when I never felt like this. However, it seems to be coming more often these days, and every now and again has become once or twice a week.

Last week Mary, on the front desk, told me I needed a wife.

Sit up, legs over the side of the bed. Late enough in the year to be sleeping with the curtains open. Early November, looking out at the tops of houses, trees behind, the ridge of the hills beyond obscured by low cloud. The feeling of apprehension still sits in the middle of my head, drip-feeding lethargy through the rest of me.

Finally stand up, stretch, and into the morning routine, which as ever ends with me sitting at the small table in the kitchen, listening to Good Morning Scotland, eating fried eggs on toast and drinking coffee. Some days feeling enthusiastic, some days feeling indifferent, some days like today, a weight on my shoulders, wondering what’s about to happen.

Into the station at just after 08:30. Nod at Mary as I walk past, but know that I’m not going to escape so easily. She either has a radar for this kind of thing, or else the signs of my melancholia are obvious to everyone, and she’s the only person comfortable enough to talk to me about it.

‘Inspector,’ she says.

‘Mary.’

I smile, slow down, try to look more enthusiastic for the day.

‘Anything happen in our one-horse town overnight?’

She narrows her eyes slightly, seeing through my attempt at casual conversation.

‘Assault outside the Horseman,’ she says, ‘but it was two hours after closing, so there’s no need to speak to Robbie.’

I lift my eyebrow in question, and she says, ‘Tom Arnold. He was kept in the Memorial overnight for observation. Head smashed against the wall, but he’ll likely get out this morning. Broken finger, a few cuts and bruises.’

‘Right. So I presume we have Debbie in custody?’

Mary smiles ruefully and nods.

We used to spend our time waiting for the inevitable break-up between those two, and the joke at the station was that when it finally happened, crime in the town would be cut in half and several of us would lose our jobs.

Time passes, however, and we’ve come to realise that they’re going nowhere. They fight and make up in a repetitive ritual, and sometimes the police are called, and sometimes it ends with one of them in hospital.

Tom and Debbie Arnold live in a large, old house on the edge of town on the Strathpeffer Road – convenient for the police station, it has been noted – and they never bother anyone else. At least there’s that. It is, however, just unutterably depressing as we watch the decline and fall, the worsening of the rift, hoping one of them will finally have the strength and sense to walk out, but knowing that when it ends it will end in the fight that goes too far, leaving one of them dead.

There was a moment, about a year after I’d been on the job. It was early morning, and I’d gone for a walk out of town on a spring day, the smell of the Highlands still fresh, new and welcoming. (Not that the sense of that ever leaves you.) I’d stopped to get a bacon roll at a van on the corner of Gladstone – a business that sadly didn’t last, despite the custom we sent its way – and was finishing off the roll as I was walking in the direction of Strathpeffer, beyond the last of the houses out on that road.

Unexpected movement to my left made me turn and look towards Knockfarrel, the hump that rises between the two towns. There were two people running towards me in what appeared, at first sight, to be a scene of Pythonesque comedy. At the front there was a man, bare-chested, unshaven, hair wild, running full pelt down the hill. Tom Arnold. Debbie was about ten yards further behind, brandishing a frying pan.

I stopped to watch, torn between walking off and leaving them to it, intervening, or being a casual spectator to this seemingly comic act. Seemingly comic, because while the scene had been taken straight from the world of seventies TV comedy, this being the real world, were she to have caught him and actually hit him over the head with the frying pan, no one would have been laughing.

With one hand on the top wire of the fence, Tom jumped over, and then he was running down the street towards me. Debbie took a little longer to negotiate the hurdle, and so fell a few yards further back.

As he passed me, the worry on Tom’s face eased for a second. He looked at me, nodded, said, ‘Inspector,’ and then continued on his way. Another couple of seconds, and then Debbie was upon me. She did the same, slowing slightly, as though slowing down might mean the police not noticing that she was actively chasing someone with a frying pan with intent to commit assault, said, ‘Nice morning,’ and kept on running.

It was perfect, and amusing in its way, and I would have loved to let them get on with it. But I was the police officer amongst the three of us. I was the adult.

I watched her for a moment and then said, just loudly enough for her to hear, ‘Debbie . . .’

She didn’t turn immediately but I could see the break in her stride. She kept running for a second, another two, three, four strides, and then finally she slowed and stopped, turning back to face me, as Tom ran on, past his own front door, not noticing that his wife was no longer in pursuit.

We looked at each other, Mrs Arnold and I, and then she said, ‘I wasn’t really going to hit him.’

The moment passed. No one was assaulted that day.

Soon enough it came though, and for years now we’ve all watched the grotesque implosion, and one day it will be over, one of them dead, one of them in prison.

‘Nothing else of interest?’ I ask, and Mary shakes her head.

For a few seconds, I wait to see if she’s going to give me any words of advice, or admonition for living alone and not sharing myself with anyone else. When it thankfully doesn’t come, I nod and walk on through to the office.

Most people already in, except Chief Inspector Quinn, who’s in Inverness for the day. Nod at a few of my colleagues in the open-plan, over to the other side, and there’s Detective Sergeant Sutherland, in the seat that used to be DI Natterson’s, a doughnut in one hand, a cup of coffee in the other, as ever at this time in the morning.

We were due to get another DI to replace Nat, but it never happened, and the replacement inspector became a sergeant. However, another sergeant post was cut so, ultimately, when it had all panned out, and the dominos had fallen, we lost an inspector and gained an administrative assistant, Police Scotland saving £34,500 a year in the process.

Sutherland smiles and nods, I return the nod and then look around the office, and on out the window, wondering what to do first.

‘All right?’ says Sutherland, through the last of the doughnut, before taking a tissue to his lips.

‘Yeah,’ I say, hands in pockets, looking out at the clouds above the rooftops across the street, and then turning to the coffee machine. Take a moment, decide to get the second cup of the day, ease myself into things and see if I can shake the feeling of gloom that still sits like a black ball in the middle of my head.

‘You all right for coffee?’ I say to him, and he lifts the mug in response, indicating it’s still half full.

‘We heading out to the Meachers’ today?’ I ask.

Fraud case, small-time, involving old European Union money. The call came from Glasgow, asking us to make some enquiries. So far it’s going slowly, but no one seems to mind.

‘Yep,’ he says, ‘should be free after eleven, if that’s good.’

‘Yep,’ I say, and turn away, walking over to the coffee machine. Constable Fisher passes by and we say hello.

And so the day begins, and just this once it turns out that my waking feeling of dread and despondency at the day is not misplaced. Soon the herald of bad news arrives, and we won’t be going to the Meachers’ place, and Glasgow and Brussels, and whoever else is asking, will just have to wait.

Chapter 10

It didn’t take long.

I’m standing at Constable Fisher’s shoulder, looking at the screen as she moves quickly down a Twitter feed.

#boyinthewell

Not yet two hours in, the social media feeds are jammed. Not so many phone calls, and the bulk of those that have come in have been quickly discounted. Some remain outstanding after the initial call, but gradually, one, two or three further calls down the line, the lead ends.

As yet, in fact, nothing has been put through from Inverness. Nothing concrete. Nothing with even the potential to become concrete.

‘What’s that?’ I say, noticing an unusual line, out of tune with all the other expressions of interest, shock, amusement and horror.

‘It’s a song, sir. REM. “The Boy in the Well”,’ says Sutherland.

‘I don’t know it,’ I say.

Fisher shakes her head, indicating her own unfamiliarity. I look at Sutherland, who’s standing next to me, a cup of tea in his hand.

‘Thought about that as soon as we found him, sir,’ he says. ‘Song was in my head. Usual kind of REM obtuse lyric, but it’s not actually about a boy in a well.’

‘It’s a metaphor?’

‘It’s a metaphor,’ he repeats.

‘What’s it a metaphor for?’

‘Being stuck in a shit life, trying to get out.’

‘Not our boy, then?’

‘Definitely not.’

‘Should I check it out?’

He shakes his head. ‘I’ll keep an ear out for anything coming in that’s reminiscent of the song.’

‘Thanks.’

Fisher jumps back to the top, looking at the latest tweets, a new batch every few seconds. On the left-hand side of the screen, the UK trends, the current list of top ten most popular items. #boyinthewell is third on the list. It was fifth when we started looking.

I don’t think we’ve been standing here long, but it’s hard to tell. How quickly one becomes wrapped up in the banality of social media.

Poor kid. Thoughts and prayers with the family. #boyinthewell

Looks like wee Ryan, Danny’s boy. Saw him last night tho, so #probablynotRyan #boyinthewell

#boyinthewell Fuck’s sake, people r cunts

Looks like Madeleine McCann lol #boyinthewell

#boyinthewell less people should be talking shite and should be looking at this. More to this than meets the eye. #conspiracy

Sad for the kid. Should of been a warning sign on the well. Someone at the council gettin his baws felt. #boyinthewell

‘Can you reply to that lady and tell her it should be fewer people?’

Fisher turns, about to object, then sees that I’m joking and smiles.

‘I’ll correct should of been while I’m at it,’ she says. ‘People on the Internet would be delighted to find that the grammar police were literally the police.’

Share the joke, then turn away with a shake of the head.

‘All right, enough, Fish, thanks. Just get rid of it for the moment, leave it to Inverness.’

‘Yes, sir,’ she says, and she closes the screen.

Sutherland and I walk back to our desks, Sutherland draining his mug of tea as we go. I feel restless. We need something to happen. We need the definitive lead, the phone call, the visit.

‘We should get back out there,’ I say, as he sits down at his desk, and I remain standing, unable to think about mundanely getting on with work.

‘The well?’

‘Yep. The ladder’s been fitted, so we can go down and have a look. If we’re going to have to wait for a positive ID, it at least gives us time to concentrate on this. And we can have another word with the happy farming couple while we’re there.’

Sutherland nods, glances at his monitor, quickly gets back to his feet.

Last look over at Fisher, to see if she’s about to turn and give me some new piece of news, worthy of the station’s attention. She’s on the phone, but her demeanour is not one of urgency.

‘Think we’ll fit down the well at the same time?’ says Sutherland, lifting his jacket and walking beside me as we head out the office.

‘With the amount of doughnuts you eat?’ I say.

He laughs, then says, ‘That’s bullying, by the way. That’ll be going in the office survey. You know what the chief’s like when the BHD scores go up.’

And we’re walking past Mary, smile and nod, and on out the station.

Despite the glib remarks on the way out, we quickly settle into sombre humour on the road to the farm. No words exchanged. Usually we’d be poring over the details of the case, but there are currently so few details to talk about that the discussion seems redundant.

All we currently have is a dead child, and we don’t know the identity of his parents. There’s very little lightness there.

We do the same as the day before, parking at the bottom of the fields, rather than driving round and up the driveway towards the farmhouse. Get out the car, doors closed, stand and survey the surroundings for a moment.

Late morning, the freshness of the new day still lingering. Very still up here, on the side of the hill. For a moment, not even the sound of a distant car, no wind to move the last of the leaves in the trees. A lone gull cries somewhere away to our right. The Cromarty Firth lies grey and still beneath us, just over a mile away, across fields and scattered homes. As ever, there is little happening out on the water. No blue sky, but the clouds are high and light, and the rain that was promised still some hours away.

I turn and look up the hill, across the fields, to the farmhouse and to the tent set up around the well. I can see Catriona Napier, sitting on the steps at the front of the house, working away at something in her hands. The only other person in sight is Constable Ross, standing outside the small white tent.

‘Seems kind of quiet,’ I say. ‘When did we take the other officers off the watch?’

‘This morning,’ says Sutherland. ‘Inverness recalled them. Or, more to the point, didn’t replace them when they went off duty.’

Another look around. Roads still quiet.

‘Isn’t it odd that more people haven’t come out? I mean, now that the kid’s become this morning’s Internet sensation?’

Sutherland follows my lead, looking around the area, becoming aware of the silence.

‘Possibly,’ he says. ‘But then, we’re on the Black Isle, sir. These people . . . well, not only are they largely hundreds of miles away, or not even in the UK in the first place, they’re on the Internet. They could be in Culbokie, but it hardly matters. The drama is playing out, there, in front of them, on their phone. Why come and stand in a cold field?’

‘They came yesterday,’ I observe, not convinced by his argument, albeit seeing no other explanation.

I open the gate, he follows me through, closes it behind us, and we start walking up the well-trodden path through the lower field.

‘The boy in the well wasn’t on the Internet yesterday,’ says Sutherland, continuing the discussion. ‘Yesterday, if you wanted to take an interest, you had to be here. Today . . .’ and he lets the sentence go.

‘The media will be back, if nothing else,’ I say.

‘I don’t know. They got their shots already. Their budgets are all just as tight as ours. Why come out to shoot an empty field with nothing going on, when they can use the shots from yesterday. Same field, lots more activity.’

We walk on. In the distance, the silence broken at last, there is the sound of an approaching car.

‘Nevertheless, Sergeant,’ I say, ‘can you get on to Inverness? We’re going to need at least two more officers back out here. If they can’t give them to us, we’ll have to do it.’

‘Yes, boss,’ he says, without any argument.

I walk on, as he takes the phone from his pocket, stopping to make the call. Up the hill, into the next field, look across at Napier but, apart from seeing each other, there’s no acknowledgement from either of us, and then I’m up to the tent by the well, Constable Ross outside.

‘Quiet morning?’ I ask, coming up beside him, then turning to look away, back down the hill.

‘Dead quiet, sir,’ he says.

‘No media?’

‘None.’

‘No onlookers or random passers-by, a car slowing as it drives past?’

‘Couple of cars,’ he says, ‘but nothing of note. They could easily just’ve been people who knew nothing about it, saw the tent, saw me, slowed down as they looked over.’

As we watch the road, a white van comes into view, SKY NEWS emblazoned on the side in red. It slows as it approaches the field, and then stops. The driver looks up at us, glances over his shoulder, and then starts reversing back along the road.

‘Crap, he’s coming up the driveway,’ I say. ‘I’ll stay here, you get over there and make sure Napier gets inside, right now, and don’t let them bug her.’

‘Yes, sir,’ and he’s off, heading over to the farmhouse even before the news van has turned into the driveway.

Still don’t know who it was making the decision to cut back on the amount of officers at the scene, but we’re back up to some sort of proper level of policing now. Those lines of tape that people are happy to step over or under or to push aside have been re-manned, allowing them to serve their purpose.

Inevitably the truth of the situation has turned out somewhere in between what I expected and what Sutherland presumed would be the case. The Internet generation aren’t here, but some locals are back, and the media have reappeared, few though they are in number.

I’m in overalls, ready to go down into the well. The inside of the tent is brightly lit, there is a light at the foot of the well and another fitted into the wall, halfway up. Sutherland is here, as is Constable Ross, who has resumed guard duty outside the tent, although he is standing half in and half out of the doorway, watching me get ready.

‘You want me to go down after you?’ asks Sutherland.

‘If you mean, when I get back up, then yes,’ I say, and he nods. ‘You should see it too, see if you spot anything I’ve missed. You should get togged up, ready to go.’

Sit on the edge of the well, feet over the side. I’m aware that Ross takes a further small step inside the tent, and turn to look at him.

‘You’re not going down yet, sir,’ he says. ‘You need a harness and a helmet.’

I glance at the table, and the equipment I’ve eschewed for the descent.

‘Excellent health and safety points, Alex,’ I say. ‘But I’m good.’

‘You’re not allowed down without the required safety equipment, sir.’

I pause for a moment, those few seconds when I decide what kind of person I’m going to be, then glance at Sutherland, who nods in return.

‘You’ll do better with the torch on the helmet anyway, sir,’ he says, ‘even with the lights in the well. And if anything happens, the harness’ll help us yank you out.’

‘What d’you think’s going to happen?’ I say, but I’ve already swung my legs back over, conceding to the inevitable.

‘You slip, you fall, you break your leg. Mundane,’ he says, ‘but hardly out of the question. And that’s not to mention the fifty or so other horror-movie-type situations that descending into a dark, confined space offer up.’

‘You’re right,’ I say, glibly, ‘give me the harness.’

And five minutes later, here I am, decked out like Constable Cole yesterday, a police expert in some sort of mining or excavation speciality.

‘Gentlemen,’ I say, nod at them both, with an extra look of acknowledgement to Ross, and then start slowly climbing down the ladder.

I’m not going to find anything new, of course. It’s not about that, particularly as the scene has now been compromised by our people, but I need to come down here. Somehow this boy was placed or dumped at the bottom of this well, and the only way to work out how it was done, is to process each possible explanation, all of which starts with Sutherland and me taking a look for ourselves.

I descend slowly, stopping briefly every couple of steps, making a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree examination of the wall. Nothing to see, as slowly the bright light of the circle at the top of the well recedes, and the lights set up within the pit take over.

Down to the halfway mark, the light on the wall at my back as I go past it.

‘Everything all right?’

Sutherland, with the obligatory call.

‘Yep!’ I shout back up, although neither of us really needs to raise our voice.

The temperature drops markedly as I near the bottom. The area where the body was discovered. Tempting to put the cold down to some evil chill, marking the place of death, but it’s logical, that’s all. A hundred feet underground, away from the sun, any warmth in the air in here rising to the top and out and away.

Nevertheless a shiver courses through me from nowhere, and I take a sharp breath as I look around. Shake it off, and focus by looking at the bare walls, the last ring of stones a couple of feet from the bottom, and the well-trampled dirt at the foot of the well.

Looking around, I wonder what became of it. Did the well run dry, or did someone decide that it wasn’t needed any more? The well itself is as much a part of the mystery as the boy, and we need to find out everything we can about it.

I tentatively put my foot down, as though expecting the floor to give way, sending me plummeting into a shaft of freezing water. I stand for a moment, and then start feeling the walls, my hands running over the old stonework. Nothing. No sign of life, no moss, no cobwebs, no worms. Not even the feeling of damp that one might anticipate. I do a full turn, shielding my eyes from the light on the floor as I pass it, inspecting the walls as I go. I begin to feel as though the bright light is impairing me, as though I’d see better with nothing but the light of the headlamp or, perhaps, with no light at all.

Stand still, close my eyes for a moment, but the light is still too bright. Open them again, look around. There’s nothing to see in any case. Bare walls that, prior to the last couple of days, hadn’t been looked upon in decades. Perhaps hundreds of years.

‘Kill the lights, Sergeant,’ I say, looking up to the circle of light, Sutherland’s head in the middle of it.

‘What?’ he shouts back down, much too loudly. The well really isn’t all that deep, and now we’ve been down here and illuminated it, the atmosphere feels completely different from yesterday morning, when Cole descended into the unknown.

I’m sure he heard me anyway. It was more a question of process, than of understanding. Why would I possibly want the lights turned off?

‘Kill the lights,’ I repeat.

My request this time is greeted by silence, and then a moment later he’s gone, and the lights are off.

I stand for a second, adjusting to this new level of dark, but with the area in front of me still illuminated by the headlamp. The quality of the light, and the features now visible in the wall of the well are different, but still, of course, there’s nothing to see. No door, no access, no way in or out.

I reach up and turn off the headlamp, then stand still for a moment in the darkness. Sutherland doesn’t leave me standing there like that for very long, however.

‘Everything all right, sir?’ he shouts down.

I look around, still aware of some vestige of light from up above, the well not deep enough for the bottom to distance itself from the brightness at the top.

‘I need darkness,’ I say, prosaically, once more turning my head upwards. ‘Can you put the wooden cover back over, please?’

‘What?’

‘Sergeant!’

I shout this time.

‘You sure?’

‘Sergeant, put the damn cover on!’

A moment, then the quieter, ‘Yes, boss,’ and his form disappears. I’m staring up at the light of the entrance to the well the whole time, then he returns, resting the roughly made wooden cover – four planks of wood nailed together, not cut into a circle – on the edge of the well.

‘Thanks, Iain. I’ll shout or tug when I want the lights back on.’

‘Right,’ he says, and then the cover is slowly lowered and pushed over, and the light quickly dims, disappearing into nothing, and the darkness is complete.

I stand for another moment, my head still staring up, as though expecting Sutherland to immediately withdraw the cover and ask if I’m sure this is what I want, and then I finally lower my head.

At last the darkness is complete, as deep and chilling as the silence that accompanies it. I stand absolutely still, eyes open, and can see nothing. The wall is no more than two feet in front of me, but it might as well not be there. For all I can see, I could be in the middle of a cavernous, underground hall.

I reach out and touch it, and then slowly circle, my hands on the wall, all the way round, until I’m back, as far as I can tell, in the same position.

The noise of the movement, the sound of my feet and the rustling of the overalls, comes to an end, and silence once again embraces the dark.

I let the silence settle into itself. Eyes still open, but they may as well not be. There is no adjustment to be made in vision down here, no trace of light to reflect off any surface. The darkness will not shift in time, the walls will not slowly creep into view.

I close my eyes, allowing the hush to slowly wrap itself around me.

What can you hear down here, beneath the ground? The workings of the world, the machine that drives the earth . . . Geological forces, grinding and pulling and fighting and squirming in eternal, monotonous rhythm . . . The gurgling of deep magma, the noise conveyed through the strata . . . The sound of a drill, carrying through rock, from hundreds of miles away . . . A vole or a mole or a mouse, squirrelling through the ground, a few yards either side . . .

Nothing. Shallow, inaudible breaths. Cannot even hear the sounds of my own body.

Yesterday morning the unnamed boy was lying down here, dead. His body was dropped into the well, from somewhere. Up there, where the opening was not opened? Or was there some strange fracture in space; he was dropped into another well, another well in another part of the world, and he ended up in here?

I allow myself this thought, something that is as absurd as Lachlan’s suggestion that he could have been down here all this time, his body somehow immaculately preserved. I don’t need to take the thought back up there, into the bright world, of light and sound.

But down here, where I can think, I need to consider all possibilities, if only so I can disregard them and concentrate on what’s left.

I think of the moment when he dropped down. Already dead, his heart already removed, no life, just sound. Forensics found no evidence of him hitting the wall of the well on the way down. A perfect drop. The whoosh of wind, a blur of pale colour, and then the loud, ugly thud as his heartless corpse hit the ground.

I’m standing where he was lying, trying to imagine him, trying to feel him. But of course there’s nothing to feel. He was never alive in this spot. What vestige of life could there be in this place?

And how long does a sound reverberate around a confined space? What is the half-life of a dull thud? Could one stand in silence and detect a noise from ten minutes previously? From an hour ago? A day?

The feel of it? The sense of it? The final, distant, minuscular vibrations. The awareness that this thing had once been here. This sound. This event. It happened not so long ago.

Yet how much noise has there been down here in the past twenty-four hours? People have come and gone, a ladder has been attached to the side of the wall, a body has been removed, pictures have been taken, boots have clumped up and down, words have been spoken, instructions have been shouted, lights shone in long-concealed corners, the equilibrium of a dead body lying at the bottom of a dried-up well has been broken.

No . . .

Silence.

I swallow, move slightly, adjusting my head, suddenly aware of the quickened beat of my heart. That sudden, horrible fear, every nerve end tensed. Listening. Trying to listen harder, in the way that one would run faster or push more vigorously. Standing in silence, ears straining.

The darkness is still complete. The si. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...