- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

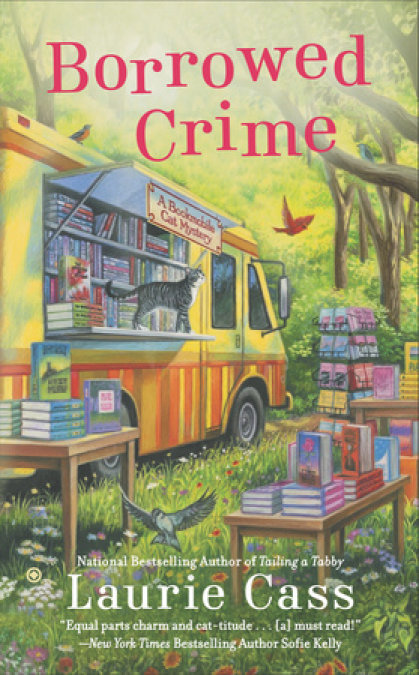

Synopsis

Librarian Minnie Hamilton spreads the joy of reading throughout Chilson, Michigan, with her bookmobile, but she doesn't ride alone. Her rescue cat, Eddie, and a group of volunteers are always on board to deliver cheer—until one of her helpers gets checked out for good . . .

When Minnie loses a grant that was supposed to keep the bookmobile running, she's worried her pet project could come to its final page. But she's determined to keep her patrons—and Eddie's fans—happy and well read. She just needs her boss, Stephen to see things her way, and make sure he doesn't see Eddie. The library director doesn't exactly know about the bookmobile's furry co-pilot.

But when a volunteer dies on the bookmobile's route, Minnie finds her traveling library in an even more precarious position. Although the death was originally ruled a hunting accident, a growing stack of clues is pointing towards murder. It's up to Minnie and Eddie to find the killer, and fast—before the best chapter of her life comes to a messy close . . .

Release date: March 3, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Borrowed Crime

Laurie Cass

Praise for the Bookmobile Cat Mysteries

Also by Laurie Cass

OBSIDIAN

Chapter 1

Some people are practically born knowing what they want to do with their lives. People like my older brother, who had his life plan scrawled out on a piece of paper by age seven, are the kind of folks who move from one goal to another, ticking things off their lists and achieving Big Things.

Other people wander through their early years without a clear path in mind, but still end up where they should have been all along. These would be people like my best friend, Kristen, who enjoyed high school chemistry so much that when the college-major decision came up, biochemistry seemed the obvious choice, and she ended up with a PhD. As it turned out, however, she did not enjoy working for a large pharmaceutical company, so she quit, came home to northern Michigan, kicked around ideas about what to do with the rest of her life, and opened up Three Seasons, which quickly became one of the finest restaurants in the region.

Then there’s me.

From age ten I knew I wanted to be a librarian, but beyond that I had no course charted out for my life. When I found a posting for assistant director at the district library in Chilson, Michigan, not long after I was handed my master’s degree in library and information science, though, I felt a ping of fate.

Chilson is a small tourist town in the northwest part of Michigan’s lower peninsula. It was where I’d spent childhood summers with my aunt Frances. It was where I’d met Kristen. It is a land of lakes and hills and has a laid-back atmosphere where “business casual” means “clean jeans and a shirt without too many wrinkles.” It was my favorite place in the entire world, and getting my dream job in a dream location was something I could not possibly have planned.

Of course, there were drawbacks, and that wasn’t even counting the facts that at thirty-three I was never going to grow past the five-foot mark, that my curly black hair was never going to straighten, and that I didn’t know how my beloved new bookmobile would handle the upcoming winter.

“He’s doing it again, Minnie,” Aunt Frances said.

We were sitting in her kitchen, because although the dining room that overlooked the tree-filled backyard was a lovely place to eat during the warm months, when the weather grew cooler, chill drafts curled around our ankles and the two of us beat a happy retreat to the warmth of the kitchen.

In summer, though, the kitchen wasn’t nearly big enough, because in June through August my aunt took in boarders. Six, to be exact: three female and three male, each of whom was single and unattached.

My aunt had an extensive interview process for her summer folks. Though she told the prospective boarders that she wanted to determine compatibility for the unusual living arrangements (the boarders cooked Saturday breakfast), she was actually starting her process of secret matchmaking. No one ever knew that they were being set up, and, in her years of taking in boarders, she’d failed only once, and even that wasn’t a complete failure.

But that had been last summer, back in the days of warmth and sunshine and a town busy with tourists. Now, in early November, the summer residents were long gone, the tourists wouldn’t be back until late May, and my aunt and I were rattling around in a house far too big for two, even with most of the upstairs rooms closed off.

Of course, sometimes it wasn’t nearly big enough for three, considering the nature of the third.

“Do you hear him?” Aunt Frances asked.

I did. I started to stand, but she waved me down. “Finish your breakfast. I’ll clean up his mess after the two of you leave. It’s not—”

“Mrr.”

Eddie, my black-and-white tabby cat, padded into the room and jumped onto my lap. His head poked up over the tabletop and he reached forward.

“Not a chance, pal.” I moved the bowl of oatmeal out of his reach. “You know the rules.”

Aunt Frances laughed. “He may know the rules, but I don’t think he has any intention of following them.”

Gently, I pushed at his head, trying to make him lie down, but he pushed it back up.

Down I pushed.

Up he came.

Down.

Up.

Down.

“You know he’s going to win,” Aunt Frances said.

“Shhh, don’t let him know.”

“From the noises we just heard, I’d say he already won the battle with the toilet paper.”

In summer, I lived at a marina on a small houseboat, but Eddie and I moved to the boardinghouse after my aunt’s guests were gone and the weather started to turn. Since then, Eddie had discovered that his new favorite toy was the roll of toilet paper in the kitchen’s half bath. And to Eddie, a toy couldn’t be a favorite unless he did his best to destroy it. Happily, toilet paper wasn’t expensive. At least in small quantities.

“You know,” I told the top of his head, “even things that aren’t expensive can get that way if you have to buy them new every day.”

Eddie had gone through bouts of destructiveness with paper products all summer long, and it looked as if the trend was going to continue. What he’d be like in the winter, I didn’t know, because I’d only had Eddie since late April.

I’d gone for a walk on an unseasonably warm day and found myself wandering through the local cemetery, enjoying the view of Janay Lake. My calm reverie had been broken by the appearance of a cat, who had materialized next to the gravesite of Alonzo Tillotson, born 1847, died 1926.

Though I’d assumed the cat had a home and had tried to shoo him away, he’d followed me back into town and charmed the socks off me by purring and rubbing up against my ankles.

I’d taken him to the vet, where I’d been told that my new friend was about two years old and needed ear drops. I’d run a Found notice in the newspaper, but even though I’d dutifully paid for a normal-sized advertisement instead of the tiny one I would have preferred, no one had called. Eddie was mine.

Or I was his. One of those.

“I’ll stop and stock up on my way home.” I got up and took our dishes to the white porcelain sink, which was so old it was trendy again. I’d seen similar ones in antiques stores selling for bizarrely large sums of money and realized that my aunt could make a fortune by taking the boardinghouse apart and selling it bit by bit. Of course, then she wouldn’t have anywhere to live. Besides, she loved the place, despite its drafty windows and problematic plumbing. And so did I.

“Do we need anything else from the store?” There was no answer. I looked over my shoulder and saw Aunt Frances still sitting, her elbows planted on the old oak table, her chin in her hands and her gaze on Eddie.

My cat was sitting in the middle of the spot I’d vacated. He was looking back at Aunt Frances with an intense, yellow-eyed stare. I knew that stare well, and it often meant trouble.

“You know,” my aunt said in a faraway voice, “I think it would be nice to get Eddie his own chair.”

Trouble, my friends, right here in the boardinghouse kitchen.

I went back to the table and gave my feline friend a gentle push, sending him to the floor. Aunt Frances started to protest, but I shook my head. “He got you again,” I said. “Beware of the power of the cat. He was trying to convince you to cater to his every whim, and he would have sucked you in if I hadn’t interfered.”

Aunt Frances laughed and got up from the table. I could tell she didn’t quite believe me. Well, I didn’t quite believe me, either, but what other explanation was there for lying awake in the middle of the night, desperately wanting to straighten your legs but not doing so because straightening them would disturb a cat’s sleep? I also didn’t believe that Eddie’s brain grasped more than a handful of human words, but there were times when it seemed as if he understood life better than I did.

My aunt, being eight inches taller than I, was a much better candidate for putting away the dishes, so I washed while she dried.

“Did you get a card from Kristen yesterday?” Aunt Frances asked.

I grinned. Indeed, I had. My best friend worked hard in her restaurant from spring through fall, then hightailed it south. The restaurant’s closing date had more to do with the weather forecast than anything else, and she studied the early-snowfall predictions of the Farmer’s Almanac all summer.

One mid-October morning, she’d tromped into the library and flung herself into my office’s guest chair. “I’m out of here,” she’d announced.

I’d glanced up from my computer. “A little early, isn’t it?” She didn’t usually close the restaurant until the first week of November. Then she drove to Key West, where she tended bar on the weekends and did absolutely nothing during the week. Come spring, after I e-mailed her pictures of melted snow and ice-free lakes, she would return, refreshed and ready for another summer of hard work. It wasn’t a life I would have wanted, but it suited her perfectly. “What’s the rush?” I asked.

She slouched in the chair, sticking her long legs out into the middle of the room. At six foot, with straight blond hair, Kristen was my physical opposite. We were opposites in other ways, too, come to think of it, the most obvious of which was that I wasn’t interested in cooking anything more complicated than canned soup, while about the only food Kristen didn’t try to improve was an apple. And even then she’d often slice it up, add a touch of lemon juice, and serve it with chunks of a cheese variety I couldn’t pronounce.

“Supposed to snow week after next,” she said. “I’ve talked it over with the staff, and they’re okay with closing down early. It was a good summer, but ‘good’ means ‘a lot of work.’ They’re tired, and I don’t want to push them.”

It wasn’t just her staff that was tired. I studied the droop of her broad shoulders and the fatigue scoring lines into her face.

“What about Scruffy?” I asked.

Last summer, I’d accidentally started a romance between Kristen and Scruffy Gronkowski, a very nice man who was anything but untidy. He was the only person I knew under the age of sixty who took the time to iron creases into his pants, and he was also the producer of a cooking show that was occasionally filmed in Chilson because the host, Trock Farrand, owned a house nearby.

She grinned. “He’s at Trock’s house, trying to figure out how to fit my restaurant into next year’s schedule.”

Jumping to my feet, I flung my arms out and ran to her, shrieking for joy all the way. She laughed and hugged me hard. “Mid-July, he thinks, so it could be a nutso-busy zoo the rest of the summer.”

Kristen’s restaurant was doing well, but having it appear on a national cooking show could zoom it past the marginally profitable zone and into a place where she could think about hiring a manager. Not that she would—she was too hands-on—but there’s a big difference between not wanting to and not being able to.

“And how does Mr. Scruff feel about your Key West destination?” I asked.

She looked at me, all wide-eyed and innocent, a look she hadn’t been able to pull off even when she had been innocent. “Oh, I didn’t tell you? He’s planning to come down for Christmas.”

I whistled. Or tried to. Whistling wasn’t one of my most developed skills. “That sounds serious.”

“Now, don’t go all wedding dress on me,” Kristen said. “My mother’s bad enough. Scruffy just hates the snow.” And that was all she’d say, no matter how sneaky I was about trying to get more information out of her.

The night before she left, we sat in her restaurant’s empty kitchen, eating the last crème brûlée in the place and drinking a bottle of her best champagne.

“Postcards,” she said suddenly.

Since we’d been guessing how long the new downtown gift shop would last—my estimate was less than a year—I blinked at her. “What?”

“Postcards. Key West is full of them.” She topped off our glasses with more bubbly. “I’ll send you a postcard every week.” She smiled, showing her white teeth, and for a moment she bore a striking resemblance to a great white shark.

“A Scruffy report?” I asked. We’d be e-mailing or texting practically every day, but the thought of getting a postcard in my mailbox was appealing.

“Maybe. But only if I get Tucker updates.”

The good-looking, blond, and tall (but not too tall) Dr. Tucker Kleinow and I had been dating since last summer. Though we’d hit a stumbling block when we discovered his allergic reaction to cats in general and Eddie in particular, our relationship was progressing nicely, thanks to Tucker’s willingness to take an allergy medication when he was Eddie-bound. “Deal.” I held up my glass, and we toasted our pact.

Now that I’d received two postcards, I was realizing what had lain beneath her sharklike smile. Postcard number one had been a picture of blue skies and sandy beaches. On the back she’d written Key West, a steady eighty-one degrees. Chilson, forty-five and dropping. Sucker.

Aunt Frances had stuck it up with a thumbtack on the doorframe to the living room, where, in a few weeks, it would be surrounded by Christmas cards. She was amused by the whole thing and had been wondering if Kristen would keep it up all winter.

Now I nodded toward my backpack, which was sitting on the end of the kitchen counter. “The new one’s in the outside pocket. Go ahead and take it out.”

Postcard number two had been a picture of blue skies and sandy beaches. On the back she’d written Key West, eighty degrees and sunny. Chilson, snow coming soon. Eww.

But Kristen knew that I didn’t mind winter. I actually liked it. Soft and white, it transformed the world into something completely different, something fresh and clean and unexpected.

I stood there, my hands in the soapy water, daydreaming ahead to skiing and skating and snowshoeing. All sorts of activities that started with the letter S were done on a substance that also started with an S, namely snow, and—

“Mrr!”

I jumped. “Right,” I said, nodding. “We need to get going, don’t we?”

From his perch on my chair, Eddie looked straight at me. I didn’t need a cat interpreter to know that he was saying, Well, duh.

Aunt Frances returned the last bowl to the glass-front cabinets. “Do you think Eddie would like a half wall? About so high”—she held her hand at waist level—“and about three feet long. I’ve been thinking about taking out this door between the dining room and the kitchen for some time. It’ll open up the space nicely. Maybe this is the year to do it.”

Smiling, I dried my hands on the blue-and-white hand towel. “You think?”

She eyed the area of interest. “It’s not a load-bearing wall. A sledge and a flat bar will take it down in no time. Then a little framing, a little drywall work, and a little trim. Shouldn’t take long.”

I snorted. “Have you ever heard that story about the shoemaker’s children—you know, the ones who didn’t have any shoes?”

My loving aunt whirled her drying towel into a tight spiral and popped me lightly with the end of it. “Out, you horrible child,” she said, laughing. “Out right now, or you’ll be late for work.”

“Mrr.”

And since they were both right, I grabbed my backpack, which was full of appropriate provisions for cat and human, and headed out.

* * *

I paused at the front closet to pull on my coat, boots, and gloves, and went outside into the dark of the predawn morning. But as I stepped off the wide front porch, empty of the summer swing that had been stored away, I saw that the world wasn’t completely dark.

The sky was gray and was forecast to stay that way for the foreseeable future, but the ground was covered with a light dusting of white.

My heart sang with pure pleasure. Maybe by February I’d be tired of the cold, and maybe come March I’d be tired of brushing snow off my car, but at this moment I was enchanted with the sprinkling of fairy dust.

Humming to myself, I started my car, set the defroster to high, and got the ice scraper from the floor of the backseat, where I’d put it at the end of September, because you just never knew.

The ice scraper had a long handle and a brush, and it had been a gift from my father when I’d bought my first car. He’d wrapped it himself, the bright yellow and red paper tight against the plastic, revealing the object’s shape so obviously that a five-year-old could have guessed what it was, and had handed it to me with gravitas. “Don’t ever take it out of your car,” he’d said solemnly. “Keep it in your trunk during the summer, on the floor of the backseat all winter.”

It wasn’t a bad idea—as a matter of fact, it was a pretty good one—and it had only taken me five years and one early snowstorm to start taking my dad’s advice.

As I brushed the snow off the car’s hood, I heard the sound of a door shutting. Which was odd, because it wasn’t even seven thirty, and the only year-round people in the neighborhood were retirees who tended to stay inside until the morning got as bright as it was going to get. The vast majority of homes in this part of Chilson belonged to summer people. They might come up at Thanksgiving, a week at Christmas, and perhaps Presidents’ Day weekend, but mostly the houses sat quiet and dark, waiting for the warmth of May to bring them back to life.

I turned and saw something completely unexpected.

Across the street, a figure was standing on the front porch, zipping up his coat and pulling on gloves. It was Otto Bingham, the house’s new owner. At least I assumed it was him; Aunt Frances had heard that a gentleman by that name had purchased the house a few weeks ago, but she’d never met him. Though she’d gone over to the white clapboard house two or three times to introduce herself, he’d never been home.

“Good morning!” I smiled and waved, thinking that I’d have to tell Aunt Frances that I’d had an Otto sighting. The light from the porch illuminated a man who looked, at this distance, like he was in his mid-sixties and on the bonus end of the Handsome bell curve.

“The snow’s pretty, isn’t it?” I asked.

He looked at me, squinting, then gave a curt nod and went back inside his house, shutting the door firmly behind him.

I stared after him, then shrugged. Maybe the guy hated snow, which would be silly for someone who’d just moved to this part of Michigan, but you never knew what made people do things.

Then I put thoughts of my aunt’s curmudgeonly neighbor out of my head, gave the car’s windshield one last brush, and headed back up the porch stairs for the cat carrier.

Because it was a bookmobile day, and no bookmobile day could be complete without the bookmobile cat.

* * *

“What I don’t understand,” Denise Slade said, “is why you feel the need to keep Eddie such a secret.”

I glanced over at my newest bookmobile volunteer, then went back to concentrating on my driving. When the road was wide and straight and dry, piloting the thirty-one-foot-long vehicle was a joy and a delight. However, most of the roads in Tonedagana County were narrow and curving, and today they were wet with slushy early snow. Then again, poor road conditions were part of life Up North, and I was mentally prepared to deal with whatever Mother Nature tossed my way. But I wasn’t so sure I was prepared to deal with Denise.

Denise was one of those stocky, energetic women who volunteered for multiple worthy organizations. She’d helped out with area environmental groups, she’d spent time on the local PTA, she’d baked cookies for the Red Cross blood drives, and she was now president of the local Friends of the Library, a volunteer group that raised funds for library projects and donated innumerable hours to helping out at library events.

Though she’d ruffled more than a few feathers with her take-charge attitude and her voice, which I’d heard described as the kind that goes straight into your teeth, I’d always gotten along fine with Denise.

Then again, that could have been due to the simple fact that I hadn’t spent much time with her.

“Eddie,” I said, “was a stowaway on the bookmobile’s maiden voyage. He followed me from the houseboat”—the marina where I moored the boat in summer was a ten-minute walk from the library— “and snuck on board when I was out doing the morning inspection.”

“Well, I know all that.” Denise looked at the cat carrier strapped down next to her feet. “And I know that you didn’t take him out again until that poor little Brynn Wilbanks cried to see the bookmobile kitty.” She paused and slid a glance over to me. “How is she these days?”

“Great,” I said, smiling. “She’s doing just great.” My smile filled me to overflowing, because five-year-old Brynn was still in remission from leukemia. She was doing so well that her mother had enrolled her in kindergarten, and the bookmobile would soon be making a stop at Brynn’s elementary school.

“Good to hear.” Denise nodded. “So, I get why Eddie started coming on the bookmobile, what with Brynn and so many other people liking him. What I don’t get is why you have to keep him a secret from your boss. Keeping secrets from Stephen is a bad idea, Minnie. Trust me on this one.”

I stifled a sigh and yearned for what could not be. My summer volunteer, Thessie, had been a perfect match for the bookmobile, for Eddie, and for me. She was funny, intelligent, and tall enough to reach the bookmobile’s top shelves without having to get on her tiptoes. She was also a senior in high school and aiming for a college major in library science. Bookmobile life would be perfect if Thessie would only drop out of school. If only she would bury her ambitions, to ride on the bookmobile for no pay and no benefits and absolutely no future.

“What’s so funny?” Denise asked.

“Just trying to picture Stephen covered with Eddie hair.”

She leaned forward and reached through the wire door to pet the feline under discussion. “You do have a lot of it, Mr. Edward.”

“Mrr.”

Hmm. Denise was a little pushy and a little too sure of herself when the circumstances didn’t warrant it, but she was a cat person, and Eddie seemed to like her. Maybe he knew something I didn’t.

Denise sighed. “Well, I hope you know what you’re doing with Stephen and all. I mean, I won’t say anything to anyone, but I have to say it’s no wonder you’re having trouble getting people to volunteer. What are you going to do on the days I can’t come out? Because I can’t promise I’ll be able to come with you every time.”

My half smile faded. I stopped thinking about my stick-to-the-rules boss, a man who wore a tie to work every day even though there was no reason to do so, a man who seemed to delight in giving me unachievable goals, a man who wouldn’t blink at firing me if he found I’d been giving bookmobile rides to a creature full of hair and dander. I stopped thinking about all of that and concentrated on keeping my voice calm when I really wanted to shout. Loudly.

“Denise,” I said, “you told me you could help out until next spring. You said you had nothing else going on and that you’d be glad to help keep the bookmobile running.”

“I did?”

She sounded puzzled, and I glanced over. She was pushing her short, smooth brown hair back behind her ears and frowning slightly, deepening the lines that were starting to form in her face.

“Yes, you did,” I said. “Please tell me you haven’t made any other commitments. I just finished the new schedule and I don’t want to have to cancel any stops.”

Making the winter bookmobile schedule had driven me to chocolate more than once. I’d made up the summer schedule with no problems whatsoever, and had blithely assumed that fall would be the same way. My blithe spirit was no longer. Despite my best intentions, the new schedule wasn’t anywhere close to what it had been in summer. But at least I now knew to contact schools and day-care centers in May about their fall programming.

And I also knew that I really needed to find money to hire a part-time bookmobile clerk instead of relying on volunteers.

Back in the days when I’d put together the bookmobile funding and worked though operation issues, the library board had laid down one cast-in-stone rule: no driving alone. I’d agreed readily, and had been happy enough to comply with their policy. Well, I’d once had to count Eddie as my bookmobile companion, but that had been a onetime thing.

Denise laughed. “Don’t be such a worrywart. I’m going to volunteer a few hours a week at the nursing home, is all. Most of the time I’ll be able to work around the bookmobile schedule.”

Most of the time? “And what happens if you can’t?” My voice was going all Librarian. “Denise, if there aren’t two people on the bookmobile, we can’t go out. I need to know in advance if you can’t make a trip. A week, at least.”

“Don’t worry,” she said. “It’ll be fine.”

I wasn’t worrying; I was thinking.

It was easy to convince folks that the bookmobile was a worthwhile cause for volunteering; all I had to do was give them a quick tour of our three thousand books, CDs, DVDs, and magazines, and tell them about the happy smiles on every face that came aboard. Selling people on how important the bookmobile was to the hundreds of people in the county who couldn’t get to Chilson, home to the only brick-and-mortar library in the county, was the easy part.

The problem was, since Thessie had gone back to school, I’d had a number of people excited about riding along. Unfortunately, almost all had canceled for various reasons, and I’d had to cleverly winnow out a few who I felt might not keep the Eddie secret. Denise was the sole survivor.

What I needed was to hire someone. Or, more accurately, what I needed was to find the funds to hire someone. Until then, I had to rely on volunteers. And if Denise wasn’t going to be reliable, I’d have to find someone else. Only who?

Thinking hard, I tapped my fingers on the steering wheel. Thought some more. Tapped. Thought.

Then the sun broke through the clouds, skidding bright light across the countryside, and I stopped thinking so hard. It was turning into a beautiful day. Why ruin it with thinking too much?

“Wow. Did you see that?” Denise stretched forward, looking up. “That was one huge woodpecker!”

“Pileated,” I said confidently. It was a newly formed confidence, because I hadn’t known diddly about birds until I started driving the bookmobile. But now that I was out and about so much, I was using the bookmobile’s copy of Birds of Michigan on a regular basis. The two weeks when someone had checked it out had been two very long weeks.

“Really?” Denise twisted in her seat, tracking the bird. “That’s neat. I bet you see a lot of nature stuff. Have you ever come close to hitting a deer?”

“No, and I hope I never do.”

She laughed. “You mean ‘not yet.’ It’s just the way things are. And deer season starts on Saturday. When those rifle hunters get out in the woods, the deer will start moving around.”

I wasn’t going to worry about that, either.

Denise was looking around, checking out the wooded roadside. “I wish I had my boo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...