- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

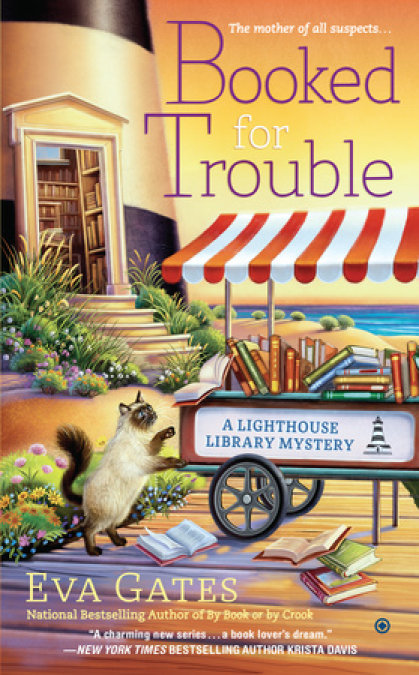

Lucy has finally found her bliss as a librarian and resident of the Bodie Island Lighthouse. She loves walking on the beach, passing her evenings with the local book club, bonding with the library cat, Charles, and enjoying the attention of not one, but two eligible men. But then her socialite mother, Suzanne, unexpectedly drops in, determined to move Lucy back to Boston and reunite her with her ex-fiancé.

To make matters worse, Suzanne picks a very public fight at the local hotel with her former classmate Karen Kivas. So, when Karen turns up dead outside the library the next morning, Suzanne is immediately at the top of the suspect list. Now Lucy must hunt down a dangerous killer before the authorities throw the book at her poor mother.

Release date: September 1, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Booked for Trouble

Eva Gates

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Chapter 1

I love my mother. Truly, I do. She’s never shown me anything but love, although she’s tempered it by criticism perhaps once too often. She believes in me, I think, although she’s not exactly averse to pointing out that I’d be better off if I did things her way. She’s a kind, generous person. At least, that is, to those she doesn’t consider to be in competition with her for some vaguely defined goal, or else watch out—she’ll carry a grudge to the grave. She may be stiff and formal and sometimes overly concerned with the observance of proper behavior, but she’s also adventurous and well traveled. And above all, her love of her children knows no bounds.

I do love my mother.

I just wish she weren’t bearing down on me at this moment, face beaming, arms outstretched.

“Surprise, darling!” she cried.

It was a surprise all right. My heart sank into my stomach and I forced out a smile of my own. I’d been living in the Outer Banks of North Carolina for a short time, making a new life for myself away from the social respectability of my parents’ circle in Boston, and here she was.

“Hi, Mom,” I said as I was enveloped in a hug. It was a real hug, too. Hearty and all-embracing, complete with vigorous slaps on the back. When it came to her children, Mom allowed herself to forget she was a Boston society matron. I loved her for that, too.

I pulled myself out of the embrace. “What are you doing here, Mom?”

“I’ve come for a short vacation and to see how you’re settling in.” She lifted her arms to indicate not only the Outer Banks but the Lighthouse Library, where I worked and lived. “Isn’t this charming? I haven’t been in this building since it was renovated.”

“You were here before it became a library?” I asked with some astonishment. When the historic Bodie Island Lighthouse had no longer been needed for its original function as a manually operated light, it had slowly crumbled into disrepair. Then, in a stroke of what I considered absolute genius, it was renovated and turned into a public library. High above, the great first-order Fresnel lens flashed in the night to guide ships at sea, while down below books were read and cherished.

“Of course I was,” Mom said. “Oh, I can remember some wild nights, let me tell you. Sneaking around in the dark, trying to break into the lighthouse. Up to all sorts of mischief.” She must have read something in my face. “I was young once, Lucy. Although it sometimes seems like another lifetime.”

She looked so dejected all of a sudden that I reached out and touched her arm. “It’s nice to see you, Mom.”

“You must be Mrs. Richardson.” Ronald, one of my colleagues, extended his hand. He was a short man in his midforties with a shock of curly white hair. He wore blue-and-red-striped Bermuda shorts, a short-sleeved denim shirt, and a colorful tie featuring the antics of Mickey Mouse. “The resemblance is remarkable,” he said. “Although if I hadn’t heard Lucy call you Mom, I’d have thought you were sisters.”

Mom beamed. I didn’t mind being told I looked thirty years older than I was; really I didn’t. Ronald was our children’s librarian, and a nice man with a warm, generous heart. He’d only told Mom what she wanted to hear. And, I had to admit, Mom looked mighty darn good. Weekly spa visits, a personal trainer, regular tennis games, and the consumption of truckloads of serums and creams (and, perhaps, a tiny nip and tuck here and there) only accented her natural beauty. She was dressed in a navy blue Ralph Lauren blazer over a blindingly white T-shirt and white capris. Her carefully cut and dyed ash-blond hair curled around her chin, and small hoop earrings were in her ears. Her gold jewelry was, as always, restrained, but spoke of money well spent.

I, on the other hand, looked like the harassed librarian I was. Only the horn-rimmed glasses on a lanyard and a gray bun at the back of my head were missing. My unruly mop of dark curls had been pulled back into a ragged ponytail this morning, because I hadn’t gotten up in time to wash it. I wore my summer work outfit of black pants cut slightly above the ankle, ballet flats, and a crisp blue short-sleeved shirt, tucked out. I hadn’t gotten around to washing the shirt after the last time I’d worn it, and hoped there were no stains so tiny I hadn’t noticed—because Mom would. I made the introductions. “Suzanne Richardson, meet Ronald Burkowski, the best children’s librarian in the state.”

“My pleasure,” Mom said, before turning her attention back to me. “Why don’t you give me the grand tour, dear?”

“I’m working right now.”

She waved her hand at that trifle.

“You go ahead, Lucy,” Ronald said. “My next group doesn’t start for fifteen minutes. I’ll watch the shop while you take your mom around the place. But,” he added, “don’t go upstairs yet. I want to show her the children’s library myself.”

Mom laughed, charmed. Ronald smiled back, equally charmed.

I refrained from rolling my eyes as she slipped her arm though mine. “Come on,” I said. “I’ll show you the Austen books, and then introduce you to my boss.”

“Is he as delightful as your Ronald?”

“He’s not my Ronald, and Bertie is a she.” I liked Bertie very much, but if there was one thing she was not, it was delightful.

I proudly escorted Mom to view the Bodie Island Lighthouse Library’s pride and joy: a complete set of Jane Austen first editions. The six books, plus Miss Austen’s own notebook, were on loan to us for a few more weeks this summer. They rested in a tabletop cabinet handcrafted specifically to hold them, tucked into a small alcove lit by a soft white light. The exhibit had proved to be successful beyond the wildest dreams of Bertie and the library board. Not to mention the local craftspeople and business owners when crowds of eager literary tourists began flooding into the Nags Head area.

“I’d love to have a peek at Jane Austen’s notebook,” Mom said. “Written in her own handwriting—imagine.”

“I’ll get the key when we meet Bertie. I’m sure we can make an exception in your case and let you hold it.” We’d learned the hard way to keep the cabinet locked at all times and to secure the only copy of the key on Bertie’s person. She’d told me that if the library caught fire in the night, I had permission to break the glass and grab the books. Otherwise, only she could open it.

Bertie was in her office, chewing on the end of a pencil as she studied her computer screen. I gave the open door a light tap. Bertie looked up, obviously pleased at the interruption. I knew she was going over the budget this morning. Charles, another of our staff members, occupied the single visitor’s chair. He stretched lazily and gave Mom the once-over.

Neither he nor Mom appeared to be at all impressed with what they saw.

The edges of Charles’s mouth turned up into the slightest sneer and he rubbed at his face. Then, very rudely, he went back to his nap.

“Oh,” Mom said, “a cat. How . . . nice.”

Bertie got to her feet and came out from behind her desk. I made the introductions, and the women shook hands.

“I hope you’re taking care of my only daughter,” Mom said. Behind her back, I rolled my eyes. Bertie noticed, but she didn’t react.

“Lucy’s taking care of us. She’s a joy to work with and I consider myself, and the library, very lucky to have her.”

Mom smiled in the same way she had at parent-teacher interview day.

I’m thirty years old and have a master’s in library science, but to Mom I’m still twelve and being praised for getting an A plus on my essay on the Brontë sisters. I felt myself smiling. In that, she was probably no different from most mothers.

“Are you staying with Ellen?” Bertie asked, referring to Mom’s sister.

“I’m at the Ocean Side.” Mom always stayed at the Ocean Side, one of the finest (and most expensive) hotels on this stretch of the coast. “I haven’t been to the hotel yet, Lucy. I wanted to stop by and let you know I’ve arrived. Why don’t you come with me and help me check in?”

“I’m working,” I said. Work was a concept Mom pretended to be unfamiliar with.

“Go ahead, Lucy,” Bertie said. “Take the rest of the afternoon off. You’ve been putting in so many extra hours—you deserve it.”

“But . . .”

“I’ll take the circulation desk.”

Between Mom’s wanting me to come with her and Bertie’s wanting to escape budget drudgery, I could hardly say no, now, could I?

Not wanting to be left alone, Charles roused himself and leapt off the chair. He rubbed himself against Mom’s leg. She tried to unobtrusively push him away. Charles didn’t care to be pushed., He was a big cat. A gorgeous Himalayan with a mass of tan-and-white fur, pointy ears, and a mischievous tan-and-white face. We walked down the hallway, while Mom tried not to trip over the animal weaving between her feet.

“Did you drive all the way down today?” I asked. Mom loved to drive, and she’d often jump into her car and take off for a few days, giving the family no notice. “Me time” or “road trip,” she called it. As I got older, I began to realize that “me time” usually corresponded with my dad’s dark moods.

“I spent a couple of days in New York, left there this morning.”

“New York,” Bertie said, almost dreamily. “I haven’t been there for ages. How was it?”

“Marvelous,” Mom said. “I did some shopping, saw a play.”

I grabbed my bag from the staff break room, leaving Mom and Bertie to talk about the delights to be found in New York City.

When I reappeared, Ronald had joined the conversation. He was from New York and had been a professional actor before giving that up to become a librarian. Broadway’s loss, I thought. Ronald loved nothing more than putting on dramatic presentations with the kids. Ronald’s children’s programs were one of the most popular things at the Lighthouse Library.

“I’d enjoy showing you what we’ve done with what little space we have, Suzanne,” he said. “If you have time, that is.”

“Of course, I do,” Mom said. “I’m on vacation after all.”

“You go on up,” Bertie said. “I’ll take the desk and then show Suzanne the notebook.”

Mom linked her arm though Ronald’s. The children’s library is on the second level. We climbed up the spiral iron stairs, while Charles ran ahead, leaping nimbly from side to side and balancing perfectly on the railing, his huge bushy tail held high.

The children’s room was a riot of color and soft fabrics. The space was small, but Ronald had divided it into sections: primary-color beanbags for sitting on, stuffed animals and cartoon characters, and bright plastic tables for the little children; pastel shades and sports team posters for the preteens; darker colors, larger chairs, and big maps on the walls for the teenagers. A scale model of an eighteenth-century sailing ship sat in the deep alcove of the room’s single window, overlooking the sea.

Mom clapped her hands. “This is marvelous. I have to bring my grandchildren here one day.”

“They’d be more than welcome,” Ronald said, clearly pleased by her enthusiasm.

“Has anyone seen— Oh, sorry. Didn’t know you had company.” The fourth member of our library team, Charlene, came into the room. Tiny blue buds were stuck in her ears and a cord ran down to disappear into her pocket. Charlene was our reference librarian, and when she was working, she enjoyed listening to music. What she considered music, anyway.

I made the introductions.

“You drove all the way down from Boston by yourself?” Charlene said. “That’s quite a trip. What do you do when you’re driving?”

“Will you look at the time?” I said. “Better be off, Mom. Thanks for the tour, Ronald.”

Mom gave me a questioning look. As well she might, but she’d be grateful to me later if I could get her out of here. Charlene was hugely intelligent, a hard worker, and an absolute darling. I adored her, but for some totally unfathomable reason her passion in life was . . .

“I can lend you some CDs if you’d like, Suzanne. I find that you can really get into new music when you’re alone on the open road.”

“That would be nice of you,” Mom said.

“Only on the condition, of course,” Charlene said with a grin, “that you write back and tell me which ones you liked the best and what you’d like to hear from my collection next. I’ll start you off with Nicki Minaj and maybe Kanye West.”

“Who?” Mom said in all innocence.

Charlene’s passion in life was hip-hop and rap music. Nothing wrong with that. Except for the fact that she was on a mission to convert the rest of us. No amount of protest could persuade her that we weren’t on the verge of conversion.

“I’ll run and make a list of what you might like right now,” Charlene said. “I’ll bring the CDs in tomorrow.” She darted out of the room, clearly delighted to have found a willing subject. Mom was so polite that she would make an attempt to listen to the records. And then she’d feel obliged to write to Charlene with her thanks. Thus opening the floodgate of further recommendations.

“You’re doomed,” I said.

“Nicky who?” Mom said. “Is that the young Estonian concert violinist everyone’s raving about?”

Ronald swallowed a laugh.

Footsteps pounded on the stairs and two girls burst into the library, followed by their mother.

“Phoebe. Dallas,” Ronald said. “Great to see you.” The younger girl dived into the pile of beanbags, while the older dropped to a crouch to examine the rows of books.

“Ronald,” the woman said, “I have a bone to pick with you.” She paid Mom and me not the slightest bit of attention. The look on my mother’s face was priceless. Suzanne Wyatt Richardson was not accustomed to being ignored.

“What would that be, Mrs. Peterson?” Ronald asked sweetly.

“Chris Bernfoot had the nerve to tell me that you recommended a seventh-grade book to her Madison. Madison’s six months younger than Phoebe. If she is reading seventh-grade material, then why isn’t . . .”

I gestured to Mom and headed for the door.

“That was incredibly rude,” Mom said as we descended the stairs. “Do you know that frightful woman?”

“Oh, yes. Mrs. Peterson is one of our most regular patrons. She is a devoted and doting mother to her five daughters. Devoted, I might add, to the exclusion of everyone and everything else in the world. She takes it as a personal affront when Ronald spends time with any other kids.” Despite their mother’s excessive attention, the five Peterson daughters were growing up to be great girls. I figured Ronald had a lot to do with that.

More running, laughing children passed us on the stairs.

“Did you like the children’s library?” Bertie asked Mom.

“Totally delightful,” Mom said.

“Now, let me show you our pride and joy. Although only temporary, I fear.” Bertie unlocked the Austen cabinet with great flourish. I handed Mom the white gloves used to handle the valuable books, and indicated she could pick up the notebook. It was, of course, a precious and fragile thing, about four inches square and an inch thick, with a faded and worn leather cover. Mom opened the book. The hand was small, the writing faded with the passage of years. Mom smiled. “How marvelous.” She carefully returned it to its place, and Bertie turned the key in the lock.

We stood quietly for a moment, no one saying anything. Then Mom shook the sentiment off, almost like a dog emerging from the surf, and said, “We’ll take my car, Lucy. I’ll bring you back.”

We said good-bye to Bertie and headed for the door. As I reached for the knob, it flew open as if propelled by a force of nature. A woman about my age, all sharp bones and jutting angles, stood in the doorway. She spotted the bag tossed over my shoulder. “Lucy,” she said. “Surely you aren’t leaving work in the middle of the day.”

“As a matter of fact, I am,” I said, shoving Mom out the door. “Gotta run. Catch you later, Louise Jane.” I dragged my mom down the path.

“Are we suddenly in some sort of a hurry?”

“Nope.” I loved living in the Outer Banks and I loved working at the Lighthouse Library. My colleagues seemed to like working with me and I was making friends. But there is always a bug in the ointment, and Louise Jane was a skinny, lantern-jawed fly buzzing around my jar.

Mom’s eye-popping silver Mercedes-Benz SLK stood out among the sturdy American vans and practical Japanese compacts pulling into the parking lot, bringing kids for the summer afternoon preteens program. Since she’d been in New York for a couple of days, she’d probably done a lot of shopping. More than would have fit into the suitcase-sized trunk of the two-seater convertible. She must have told the stores to send everything to the house.

“How’s Dad?” I asked.

“Busy. Some silly deal with some silly Canadian oil company has run into problems.”

My dad was a lawyer, partner in Richardson Lewiston, one of Boston’s top corporate law firms. “You know your father. Always working.” Mom gave me a strained smile. Outside, in the brilliant North Carolina summer sun, I saw the fine lines edged into the delicate skin around her eyes and mouth.

I climbed into the passenger seat of the car, and we roared off in an impressive display of engine power.

I knew perfectly well that Mom had not come for a visit, or to see that I was settling in nicely. She’d come to try to take me home.

Chapter 2

I pushed thoughts of Boston aside and stared out the window as the SLK pulled out of the lighthouse road onto the highway that wound through the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. It was a perfect Outer Banks summer day of blue sky, soft breeze, and warm sunshine. Not to mention plenty of tourists. Gulls circled overhead and sand drifted onto the road, but the ocean itself was hidden behind dunes and scruffy vegetation struggling to survive in the sea air and poor soil. The top of the car was down, and I took my hair out of its ponytail to let the wind, heavy with salt spray, blow through it. Mom chatted about the play she’d seen in New York, and I made the occasional grunt to indicate I was listening. After a few miles, the highway splits: left to the bridge to Roanoke Island and the charming town of Manteo, right to Nags Head and towns to the north.

We went right, down Virginia Dare Trail, past rows of brightly colored beach houses perched high on stilts to provide views over the dunes (and place them above hurricane waters), and hotels, restaurants, bars, and shops catering to summer visitors. Soon Mom slowed and turned down a private drive. Sea oats and beach grass gave way to a pebbled parking area outlined by huge pots overflowing with flowers in controlled colors of purple, white, and yellow. The hotel had been built in the 1950s but made to look much older, constructed in the memory of a grand old Southern plantation: three stories, painted a pale yellow, with a wide white veranda wrapping around three sides, a long balcony on the upper floors, framed in white Greek-style pillars. To the side of the building, I caught a glimpse of the weather-stained boardwalk leading to the ocean.

The car pulled to a stop in front of the wide, curving staircase, and the valet, dressed in a uniform of forest green jacket and knee-length breeches, rushed to open Mom’s door. I clambered out without assistance. Mom tossed the valet her keys, leaving him to bring in her bags, and we mounted the stairs. While Mom checked in, I glanced around. I hadn’t been here in many years. When my brothers and I were children, we used to come to the Outer Banks every summer to stay with Mom’s sister, Ellen, and Ellen’s husband, Amos. I still think of those lazy, happy summers as the best days of my life. Dad had never accompanied us—work, of course—and Mom had come less often as we got older. She never stayed at Ellen and Amos’s house, where she would have been welcome, but always here. Always alone.

More me time, I guess.

Mom and Aunt Ellen came from a family of small means. My granddad had been a fisherman. His father had deserted the family when my granddad was only days old, but my great-grandmother had worked hard and raised her only child well. She’d died long before I was born and I’ve always been sorry not to have known her. My mom’s mother, another hard worker, had been a cashier in a shop. I thought those were roots to be proud of, but Mom was never anything but ashamed of her hardscrabble origins.

I glanced around the hotel lobby. Marble floors, rich red carpets, wood-paneled walls, gleaming brass accents, lush palm trees in brass pots. Only one clerk was behind the reception desk and two people were ahead of Mom in the line. She was tapping the toe of her left espadrille impatiently. I leaned up against a wall. Plaster and paint were peeling where the ceiling met the wall. When I looked closer, I could see stains on the rugs, hairline cracks in the baseboards, a bad gouge in one wall, and a thick layer of dust coating the wide leaves of the potted palms.

The flowers on the round table in the center of the room were not fresh, but fading silk, covered in more dust. An air of neglect hung over the place, along with the overly strong scent of cleaning liquid. I wondered if the hotel was in financial trouble or merely trying to implement “efficiencies.”

A van pulled up in front, and through the streaked glass doors, I saw a pack of almost identically dressed, camera-toting Japanese tourists spill out. The receptionist gave a quick glance out the window. Her shoulders visibly slumped and I sensed that no one would be rushing to help her check the new arrivals in.

“Suzanne Richardson,” Mom announced. It was her turn at the desk. The receptionist switched her smile back on and said, “Mrs. Richardson, good afternoon.”

Mom joined me, key card in hand, a minute later. “I swear the service here gets worse every time I come.”

She’d been given a room on the second floor, and the elevator whisked us up. Now that I’d noticed signs of poor repair, I was seeing them everywhere. Scratched paint, a missing section of baseboard, ripped wallpaper, cracks in the elevator mirrors. Small and unobtrusive, but things like that didn’t stay small—or unobtrusive—for long.

A cart loaded with towels, cleaning equipment, and an open garbage bag was parked about halfway down the corridor. A woman came out of a room as we approached, a bundle of sheets wrapped in her arms. She wore the plain gray dress of the housekeeping staff, and her thick black hair was pulled into a knot.

“Karen. Hi,” I said.

“Lucy, what brings you here?” She pushed a wayward lock of hair off her forehead. She glanced at my mom.

“I’d like you to meet—” I began, but Mom was almost dashing down the corridor. “My mom’s visiting.”

“That’s your mother?” Karen asked.

“Yes.”

“Well, well. She’s arrived at last, has she?”

We watched as Mom stuffed the key card into the slot. She shook the door handle, and when nothing happened, she ran the card through again. The door swung open and she disappeared at a rapid clip.

That was uncharacteristically rude. Mom could always be counted on to be polite, although not overly friendly, to waiters and hotel staff.

“What’s she call herself these days?” Karen said, watching the closed door.

“Suzanne Richardson,” I said. “Do you know her?”

“I did. Once.”

It sounded to me as though, if they’d known each other in the past, they hadn’t parted on good terms. I changed the subject. “Are you coming to book club tomorrow? Did you read the book?”

She turned back to me. “Yes, I did. I hope to make it. You know how much I love the book club. But they laid off two more of the maids and that means more work for the rest of us. Then I have to get home and make dinner, and . . .”

Since getting the Austen collection, we’d found—to our considerable surprise—a keen interest in the classics among Outer Banks residents and visitors. So far the classic novel reading club had been a great success, and the members had been able to discuss the chosen novels with much argument and enthusiasm.

“I understand,” I said. I tried to like Karen—I really did—but her constant whining put my teeth on edge. Karen usually stayed after book club to help me clean up. But her real purpose, I thought, was to make sure I knew how hard done by she was.

“I’ll let you get back to your work.” I hurried after Mom.

She’d left the door open for me, and when I came in, she was standing in front of the French doors. The room opened onto a spacious balcony overlooking the beach and the ocean. People splashed in the waves, relaxed in deck chairs, or strolled along the waterline.

“That was rather rude, wasn’t it?” I said. “Karen belongs to my book club and I was going to introduce you.”

“I’m sorry, dear. Perhaps I’m more tired than I realized.” She turned and faced me. “At least the view is as lovely as I remember. Let’s go down for a drink. I’ll unpack later.”

“You have to drive me back to the library.”

“One glass won’t hurt.”

“I guess. If you want, I can take your car and get someone to come back with me to drop it off later.” My mom wasn’t much of a drinker, so I had no problem with her having one now if she wanted. As long as she didn’t try to drive.

She shrugged.

I looked at her closely. A heaviness I’d never seen before lay behind her eyes. “Are you okay, Mom?”

“Perfectly. Why wouldn’t I be, dear? It’s been a long day. Perhaps I’ll have an early dinner tonight. You will join me, of course.”

“Sorry, but I can’t. I’m going out with Josie and some of her friends.”

“You can cancel that.”

“I’d rather not. You and I have lots of time to spend together. Why don’t you come to my book club tomorrow night? You’ll enjoy it. We’re reading Pride and Prejudice.”

“Perhaps. Actually, Lucille, darling, there’s something I’ve been wanting to talk to you about. Let’s go down to the lounge and have a little chat.”

Oh dear.

The lobby bar was filling up with new arrivals, but we were shown to a quiet corner by the window. We settled into two wingback chairs covered in pink chintz. A dark stain marked the back of Mom’s chair and I expected her to refuse to sit there, but she didn’t even seem to notice. We admired the view while we waited for the waitress to arrive. A man dressed in overalls and a large straw hat was sweeping sand off the boardwalk, collecting plant refuse, and tossing it into a bucket at his feet.

“The hotel might be falling down around our ears,” Mom said, “but if they can keep the grounds looking good, I’ll continue to come here.”

“Good afternoon, ladies. Can I get you something to drink?” A smiling waitress appeared at our table. She put down coasters and cocktail napkins.

Mom ordered a glass of Pinot Grigio and I asked for hot tea.

“If I remember

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...