I awake.

Her face is the first thing I see.

“Hey, are you okay?”

Wispy blonde hair swept over the side of her head past her left ear, right side shaved. Green eyes, long lashes. Small silver nose stud, left nostril. Robin’s-egg-blue hoodie. Looming above her are ashy pine trees, naked, stripped of green and bark, pale-white ghost trees like skeletal fingers pointing accusingly at the sky.

“How many fingers am I holding up?” she asks, still filling up my vision, like she and the trees and the sky are the only things in the world.

“You’re . . . you’re not holding any fingers up,” I say. My voice is that of a stranger, totally unknown to me.

A monster steps into view behind her. He’s some kind of crab thing, with spiny legs where each ear should be. He has a computer interface blinking in the center of his chest, wires curving out and going to his back. As monsters go, he’s pretty short.

“Is he dead?” Crab-Face asks.

She rolls her eyes without looking back at him. “You just heard him talk, dummy.”

The crab monster removes its head to reveal a brown-haired kid with glasses underneath, four or five years younger than the girl, but with the same green eyes. “Don’t call me a dummy, dummy. Look at his skin. He looks like a zombie’s ghost.”

I raise my hands in front of my face. The fingers sticking out of my fingerless biker gloves are indeed chalk white and deader looking than the dead trees creaking overhead. My breath catches in my throat.

“Oh my gosh, look at his eyes!” The boy staggers back. “He’s got red eyes! Zombie ghost vampire!”

“You know, Clark, you don’t have to say out loud literally every single thing that pops into your head, right? You’re gonna freak him out.” She stands up and reaches out her hand to help me up. “Ignore my brother. It’s what I do. I’m Kalea.”

I get up. It’s harder than I thought it would be. The ground is extremely uneven. When I’m on my feet, I look around and see why. The ghost trees on the edges of the clearing got off lucky. All around me are smashed trees, some charred and blackened, some reduced to gray, powdery, ashen versions of their former selves. Some are still steaming; some are still smoking. It’s hard not to notice that the flattened trees all radiate out from me, where I’d been lying. I’m literally at the center of this.

“Yo, man!” Clark snaps his fingers inside the plastic claw covering his hand. “My sister just told you her name, now you’re supposed to tell her your name. That’s how we usually do things in, you know, nonundead society.”

“Clark!” Kalea snaps at him, but then looks back at me and says, more gently, “What . . . is your name?”

It’s a perfectly normal question. One everyone above the age of two should know the answer to. But it beats me. I look down at myself, as if there are answers there. I am wearing dark-green cargo pants, spotted here

and there with ash. I put my hands in my many pockets. They’re all empty. I touch my chest. I’m wearing a black T-shirt with no logo.

My chest tightens with panic. My brain buzzes with questions for which it has no answers. I feel dizzy all of a sudden, like I woke up on the top of a tall cliff, and in the act of waking, I’m going to stumble over the edge accidentally.

Is this what it feels like to be born? To have everything come at you, all at once, with no preparation or warning? Is that why all babies come out crying?

It’s hard to keep my feet under me. I stagger, but she’s there, and she grabs onto me. I’m ashamed. I try to look anywhere but her eyes, but she moves her face with mine until I don’t have a choice.

“It’s okay. Hey! Look at me. It’s gonna be okay. Let’s get you back to the road where we can call for help.”

“C’mon, Kalea, what about our movie?” Clark whines.

“Jeez, Clark, can’t you see he’s in trouble? Forget the movie. Just grab our stuff and we’ll come back to shoot tomorrow.” She squeezes my hand in hers and leads me stumbling across the fallen trees.

“I’ve got Scouts tomorrow,” Clark mutters but turns, grabs a bucket full of little men—action figures?—and a collapsed tripod off the ground, and follows us.

The devastation of the clearing doesn’t last long. Within minutes we’re surrounded by trees, bushes, the trickle of a brook, the rustling of squirrels chasing each other overhead, blue jays squawking out the boundaries of their territory.

“I’ve been coming into these woods all my life,” Kalea is saying, “and I’ve never seen a section flattened like that. That wasn’t there last week. You see what did that?”

I shake my head. There’s just nothing there. “I don’t know anything that happened before you woke me up.”

“Ooh, boy. You don’t look that hurt, and you seem to be walking fine, but I guess we should call an ambulance. Service out here stinks, but once we get to the road, I’ll call nine-one-one. Okay?”

Not knowing what else to do, I nod.

I could let go of her hand, but I don’t.

We emerge from the woods into an empty parking area with a trio of picnic tables in

the side grass. The sun is dipping low and red near the tree line. The sight is stunning to me, whose entire life story has only lasted ten minutes.

Where Kalea is is fifty-eight degrees Fahrenheit, or, if you prefer, fourteen degrees Celsius. Where Kalea is is forty-two minutes past nineteen hundred hours, Eastern Daylight Time. Where Kalea is is forty-one degrees twenty-six minutes north, eighty-one degrees eighteen minutes west.

These impressions come to me in a voice that is not a voice, that is in my head without entering through my ears first. I look to Clark to see if he heard it too, but he’s just staring at his feet and grousing about all the famous directors, like Ethan Cohen and Lilly Wachowski, who have supportive siblings who don’t try to ruin their careers single-handedly. “You know, I was absolutely planning on thanking you in my Oscars speech, but now? I’m not so sure.”

I turn back to Kalea, and she has a cell phone to her ear, and that’s when outside data starts flowing inside my head again:

Kalea is calling the numbers nine, one, and one. The request is being routed through a cellular base station approximately eight miles to the southwest, or, if you prefer, 12.87 kilometers.

Request picked up by County Dispatch. Connecting . . .

“Nine-one-one, what is your emergency?” says an actual voice in my head this time, a woman’s voice. The dispatcher’s name is Joelle Newsome. This is the tenth hour of her double shift. I can hear the weariness in her tone.

“Hi, uh, yeah, my name is Kalea Derby? And we found a kid, uh, a boy, like, maybe sixteen? Lying out in a smashed-up part of the Greenwood Glen. He doesn’t know his name or how he got there, and while he doesn’t look like he has any injuries, his skin is really chalky and his eyes are super red. Who knows how long he’s been out there?”

“Is he conscious? Can he walk?”

“Yeah, he’s conscious. He can walk. But we are out in the middle of nowhere, and I don’t have a car, and neither does he—”

“I am sending an ambulance. Please confirm your location.”

“We’re in the Greenwood Glen parking lot, between, uh, Bell and River Road.”

“The ambulance should arrive in about twenty minutes. Keep him sitting up and talking until then.”

“Okay, got it, thanks.” She ends the call and turns to me. “Ambulance should be

here—”

“In twenty minutes,” I say without thinking. “And I should stay sitting up and talking until then.”

“Yeah.” She blinks with a puzzled smile. “You heard that?”

I nod. I choose not to say anything about machine telepathy. She’s returned the phone to her pocket, but it won’t stop talking to me.

Kalea’s favorite contacts are her brother, Clark; her mother, Carrie; and Rosie’s Pizzeria. Mason Miller is in Favorites too, but she hasn’t called him in over a year. Here are videos of Clark blowing up, melting, dismembering, and otherwise tormenting various action figures in various monster costumes. Here’s a photo of her blowing out candles on her sixteenth birthday. Here’s her at the rec center pool with the other lifeguards. Their names, from left to right, are Mason, Liliana, Ruby, and—

That’s enough. Kalea’s phone is an oversharer. I close my eyes and silently tell it to stop deluging me with info. The data stream immediately goes dark.

“Oh no!” Kalea cries when she sees my strained expression. “You’re not feeling—worse, are you?”

“Maybe his guts are all gnarly and messed up inside,” Clark says, but trails off as Kalea shoots him a nasty look.

“No.” I shake my head. “Just a lot going on all at once.”

She laughs and claps me on the shoulder. “Yeah, I bet. Well, help’s on its way. It’s almost over.”

I nod in agreement, even though I don’t believe her.

I sense the ambulance before I see it rounding a bend up the road. Each piece of electronic equipment inside the vehicle pulses or hums with a distinctive frequency, like sections of an orchestra. The defibrillator practically trembles with anticipation: It can’t wait to shock a dead heart back to life. The radio is a gossip, crackling with reports of other people’s misery. The air-powered respirator sits holding its breath.

Both EMTs get out of the ambulance after parking it across three spaces. They are a man and a woman, both with very close-trimmed hair. They roll a gurney out of the back and ask me to get up on it.

“We’re going to strap you in for the ride to the hospital,” the woman says, patting the pillow.

“Strap him in?” Kalea frowns. “Really?”

“Standard procedure,” the man says, “in case he has internal injuries.”

“It’s okay,” I say, and get in. They tie straps around my ankles and wrists.

I say goodbye to Kalea the same way I said hello: with her leaning in puzzled concern over my prone body. “Okay, then. I hope, uh, everything turns out all right. I’d give you my email for you to let me know how it goes, but you don’t have a phone.”

“Don’t worry, I’ll find you,” I say.

Kalea frowns in surprise, and I hastily add, “To thank you, I mean.” Of course I can’t tell her that her own phone has already cheerfully told me without prompting her cell number, email address, street address, and locker number at school (126). It even flashes me a satellite photo of her house before I tell it to cut it out.

“Good luck, Mystery Man.” Clark waves as the EMTs roll me into the back of the ambulance. “We won’t forget you, even though I bet you’re gonna forget us.”

The male EMT sits by my side while the female EMT gets behind the wheel. As the ambulance drives away, I crane my head up and see through the back windows Kalea and Clark still standing in the middle of the street, watching me go as the vehicle turns a bend, and then they disappear behind black birches. I have a sudden pang of separation anxiety, and Kalea’s green eyes float in my memory briefly before fading. They are the first two people I’ve ever met, or at least that I can remember meeting, and it feels profoundly sad to see them go.

The driver speaks into a military-style satellite phone with much better encryption than Kalea’s. It will only talk to me in pops and hisses. I’m pretty sure that if I had the time, I could persuade it to open up, but I don’t have the time.

“Package secured and en route to pickup point,” she says into the phone, then clicks off without waiting for a response.

They are not taking me to a hospital.

I look at the EMT sitting next to me, looking down at me with his cold eyes. I can see a dark dab of blood on the collar of the uniform jacket that’s too big for him. Rodriguez is etched on the name tag of this blonde-haired, blue-eyed man.

I may not have any

memories, but apparently I have instincts.

My instincts say things are about to get messy.

A few kilometers later, I sense sophisticated laser-targeting weapons moving rapidly above me. The encrypted chatter spikes, pinging off satellites high in the sky. Advanced flying machines, gyros or hovers, approach, slowing, preparing to land.

I meet Not-Rodriguez’s gaze with my own.

“Who am I?” I ask.

I’m a little surprised when he chuckles. “You wouldn’t believe me if I told you.”

I can hear the gyros now, barely—they’re definitely gyros—whining above the thrum of the ambulance’s tires. They’re overtaking the ambulance to land in front of it; even now, it’s slowing down.

“I believe you,” I say.

I snap out of all four restraints at the same time effortlessly.

Not-Rodriguez loses the smile. “Tango!” he barks at the driver. He reaches inside his jacket. Everything slows down, as if I’m watching a film of this after the fact, in a small cubicle, studying the footage for strengths and weaknesses, as opposed to experiencing it in real time.

My muddy boot is on Not-Rodriguez’s throat and pinning him back against the cabin before he can draw the pistol out of his jacket. By the time he does, my fingers are already wrapping around it. It’s a Beretta 92FS semiautomatic, standard US military sidearm for decades.

I can’t spell my own name, but I guess I have an encyclopedic recall for guns. Go me.

Not-Rodriguez manages to shoot the floor, but I yank the Beretta out of his hand. The finger that’s in the trigger guard snaps like uncooked spaghetti. I didn’t mean to do that, but I don’t have time to feel bad about it either.

He tries grabbing my throat, pressing against my leg. I smash the pistol into the side of his head, and he goes limp. I drop-kick him to the floor and roll off of the gurney, but when I’m on my feet, I’m looking at a .50-caliber Desert Eagle pointed at me by the driver. The hand cannon kicks with three roars in her hand, I’m punched twice in my chest and once in my arm, and back I go through the doors in the rear of the ambulance and bouncing, tumbling across the hard gravel of a back road.

Finally, I’m able to stick a foot out and stop my backward momentum. Before me

is a big factory or warehouse, long abandoned to graffiti taggers and stone throwers. The sky is alive with giant bugs with three spinning vertical propellers for wings, and they shoot blinding lights down on me.

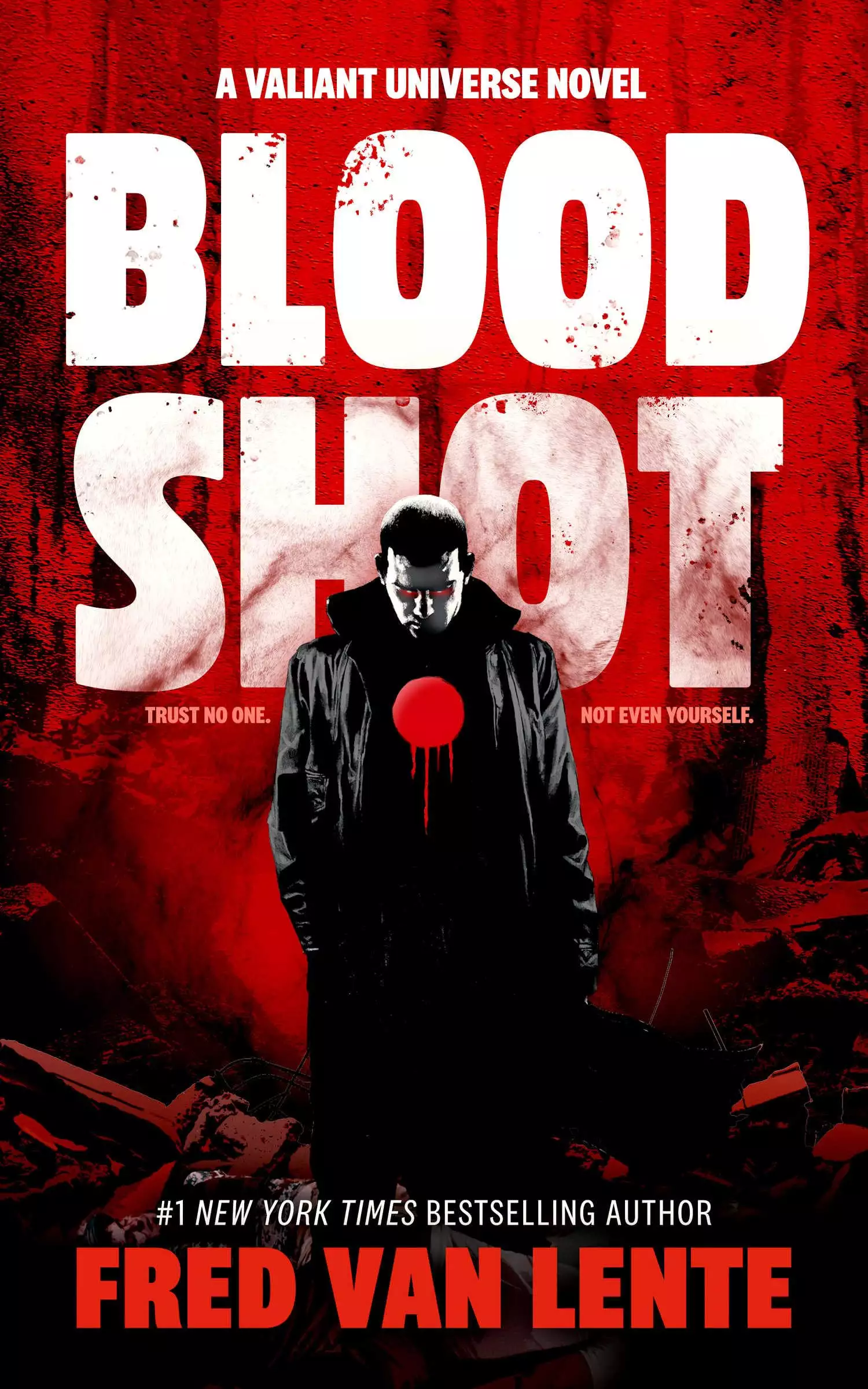

“Bloodshot,” booms a bullhorn overhead, “there’s nowhere to run. This doesn’t have to be hard. Surrender now and let us get you some help.”

These guys murdered at least one, probably two, ambulance drivers to snatch me up. Trusting them to help me is not on the table.

I’ve managed to hold on to the Beretta. I grip it tighter and sprint toward the giant brick hulk in front of me. The voice from the loudspeaker begins to say a swear word but is cut off by the sudden high whine of an M134 NATO Minigun spinning to life from its open side compartment. The big barrel spits bullets at me, but I manage to outrun the gunner’s arm and dive through the giant yawning cavity of the loading dock before I get hit.

That time, I mean. The female not-EMT already shot me three times. My chest and arm sting, and I look down at my wounds and nearly cry out at what I see:

The blood spilling out of the smoking holes in my T-shirt changes its mind midstream and starts crawling back up into my body through those same holes. The wounds then pucker like lipless mouths and close, sealing up altogether as if my injury were just a bad dream from which I’ve already woken up.

A chill runs down my spine that I’m sure I won’t heal so easily from.

“Who am I?” may not be the right question to ask myself.

“What am I?” could be the more important one.

The gyros shine their floodlights through what’s left of the windows in this dump, everywhere except where I am. There are four individual floods, so I guess there must be at least four birds in the air around the warehouse, but the creepy thing is they don’t make any more noise than the wind through the trees. They’re so quiet the thuds and grunts of the men landing on the roof three stories above me are louder than the aircraft they’re jumping from.

Once again, I don’t have thoughts; I have impulses. My body knows better than my brain about, well, everything, apparently, and it’s screaming at me to move. They’re expecting me to hide. The bugs circle the warehouse perimeter with their lights, thinking they’ve boxed me inside. The men with guns (I don’t see the guns, but come on, they're

there) are rappelling down one by one, gathering on the roof in a show of force to come down and flush me out. They’re expecting to overwhelm me with numbers.

I see a rusty ladder that has not totally rotted away from the wall leading up to the catwalk overhead. I take a running start, leap halfway up to grab the rungs, and scamper the rest of the way like I’m half-spider. I put a foot up on the railing of the catwalk and leap straight up through the skylight above.

I explode out onto the roof in a hail of frosted glass. There are six of them already on the roof, with two more coming down from cables dangling from the gyros overhead. They’re wearing full-body armor and face-plated helmets so I can’t see their expressions when I show up.

But I can see myself in the reflections of their visors, and I look pretty darn scary to me.

I land right on the first guy, ...