- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Outlander meets post-Civil War unrest in this nonstop sequel to Sawbones.

Laura Elliston and William Kindle are on the run—from the Army and from every miscreant in the West eager to claim the $500 bounty for Laura’s capture as their own. But the danger isn’t just from those pursuing them. Laura and Kindle have demons of their own and a past that won’t stay dead. Exhausted, scared, scarred, and surrounded by enemies, neither realize the greatest danger is yet to come.

Release date: May 23, 2017

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

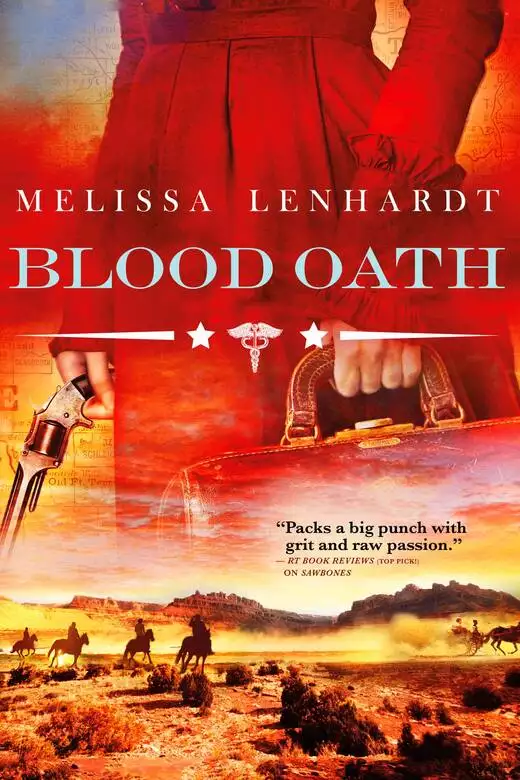

Blood Oath

Melissa Lenhardt

“Hail the camp!”

His appearance was no more or less disheveled and dirty than the other men who happened upon us, but his stench was astonishing, stronger than the smoke from the fire that lit his grimy features. His was not a countenance to inspire confidence in innocent travelers, let alone us. The left side of his face seemed to be sliding down, away from a jutting cheekbone and a brown leather eye patch. When he spoke, only the right side of his mouth moved. Though brief, I saw recognition in his right eye before he assumed the mien of a lonely traveler begging for frontier hospitality always given—and often regretted.

“Saw your fire ’n’ hoped to share it with you, if I might.”

“Of course, and welcome,” Kindle said.

“Enloe’s the name. Oscar Enloe.”

“Picket your horse, and join us.”

“Already done. Picketed him back there with yours. Nice gray you got there. Don’t suppose he’s for sale.”

“Not today.”

Enloe glanced around the camp, a dry, wide creek bed with steep banks, which offered a modicum of protection from the southern wind gusting across the plains. Our fire flickered and guttered as Enloe sat on the hard, cracked ground with exaggerated difficulty and a great sigh. He placed his rifle across his lap and nestled his saddlebags between his bowed legs.

“Well, it figures. Every time I see a good piece of horseflesh he’s either not for sale or I don’t have the money. Turns out it’s both in this case.” Enloe’s laugh went up and down the scale before dying away in a little hum. His crooked smile revealed a small set of rotten teeth that ended at the incisor on the left side. He removed his hat and bent his head to rustle in his saddlebag, giving us a clear view of his scarred, hairless scalp. I cut my eyes to Kindle and saw the barest of acknowledgments in the dip of his chin. His gaze never left our guest.

Enloe lifted his head, expecting a reaction, and was disappointed he did not receive one. I imagine he enjoyed telling the story of how he survived a scalping, since so few men did so. I was curious but held my tongue, as I had every time we met a stranger. Tonight silence was a tax on my willpower, the strongest indication yet I was slowly coming out of the fog I’d been in for weeks.

Enloe pulled a jar out of his bag. “Boiled eggs. Bought ’em in Sherman two days ago. Like one?” He motioned to me with the jar. I shook my head no.

“Dontcha speak?”

“No, he doesn’t,” Kindle said.

“Why not?”

“He’s deaf.”

Enloe’s head jerked back. “Looked like he understood me well enough.”

“He reads lips.”

“You don’t say?” Enloe shrugged, as if it wasn’t any business of his. “Want one?”

“Thank you,” Kindle said.

Enloe opened the jar, fished out a pickled egg with his dirty hands, and handed it to Kindle, along with the tangy scent of vinegar. Kindle thanked him and ate half in one bite. “What’s the news in Sherman?”

“Where’d you come from?” Enloe shoved an entire egg into his mouth. I watched in fascination as he ate on one side and somehow managed to keep the egg from falling out of the gaping, unmovable left side.

“Arkansas. Heading to Fort Worth.”

“Fort Worth?” He spewed bits of egg out of his mouth. Some hung in his beard. “Ain’t nothing worth doing or seeing in Fort Worth. Wyoming’s where the action is.”

“I’m not much for prospecting. Looking to get a plot of land and make a go of it.”

“This here your son?” Enloe’s eye narrowed at me.

“Brother.”

“Well, bringing an idiot to the frontier ain’t the smartest thing I ever heard. He won’t be able to hear when the Kioway come raiding, now will he?”

“I’ve heard tell the Army protects the settlers.”

Enloe laughed derisively. “Fucking Army ain’t worth a tinker’s damn. Except those niggers. Now, there’s the perfect soldier. Those white officers order them to charge and they do ’cause they’re too stupid to do anything but blindly follow orders. Can’t think for themselves. Redskins mistake it for bravery and won’t go up against them.” The corner of Kindle’s eye twitched, and I knew it took great resolve to not contradict Enloe.

Enloe brought out a bottle of whisky, pulled the cork, and drank deeply from the corner of his mouth. “If you’re expectin’ the Army to protect you, better turn right around and go back to Arkansas.” He narrowed his eyes. “You’re awfully well-spoken for an Arkansan.”

“Our mother was a teacher.”

He nodded slowly. “Suppose you’ve heard about the excitement in Fort Richardson.”

“No.”

“Surely you heard about the Warren Wagon Train Massacre? You do got papers in Arkansas, dontchee? Suppose not many a you hillbillies can read it.” I doubted Oscar Enloe knew a G from a C.

“We heard about it,” Kindle said. “Did they catch the Indians?”

“They did. Sherman himself, though it was pure luck. The redskins were at Sill, bragging about it. Well, Sherman didn’t give a damn about the Indian Peace Policy and arrested ’em. Shocked he didn’t put ’em on trial right there and tighten the noose himself. They sent them to Jacksboro to stand trial. One of ’em tried to get away and was shot in the back. One less redskin to worry about, I say. Other two were convicted, ’course.” Enloe held out his whisky. “Want some?”

Kindle refused. I held out my hand. Enloe ignored my knobby fingers wrapping around the bottle, foreign to me even now, weeks later, and turned his attention to Kindle. I drank from the bottle and held the rotgut in my mouth, barely resisting the urge to spit it into the fire. It was whisky in name only. The liquid scorched my throat as I swallowed, burned a hole in my stomach. I held the back of my hand to my mouth and saw Enloe watching me with a knowing smirk. Keeping my eyes on him, I drank another swallow, didn’t wince as it made its way down, and kept the bottle. I only hoped it would numb the pain before Enloe tried to kill us.

Kindle didn’t move, flinch, or take his eyes from Enloe. His rifle lay on the ground next to him, out of reach. Neither moved. “You’d think the massacre and hanging Injuns would be enough to be going on with, but that ain’t even the most interesting story outta Jacksboro,” Enloe said.

“No?”

“Jacksboro was overflowin’ with people there celebrating, wanting to see those two redskins hang. Gov’nor killed their fun, staying their execution. I imagine they’ve turned their attention now to the fugitives.”

“Fugitives?”

“The Murderess and the Major, that’s what the newspaper’s calling them. Catchy name, at that.”

“Never heard of ’em.”

“Woman who survived the massacre, turns out she’s out here on the run. ’Course, she ain’t alone in that, is she? Heh-heh. Supposed to have saved the Major right after the massacre, but we have it from his nigger soldiers so it’s probably a lie.”

I bristled and drank more of Enloe’s whisky to avoid speaking.

“Yep, she killed a man in New York City. Her lover, they say, and I believe it. Just like a woman, she lured the Major into fallin’ in love with her. He threw his career away to go off an’ save her from the Comanche, and then sprung her before the Pinkerton could come take her back to New York.”

Enloe put a finger against one nostril and shot a stream of snot onto the ground. “Some think they headed north to the railroad, or maybe south to Mexico. The Pinkerton thought they stayed in the tent city sprung up outside a Jacksboro for the trial. Tore it to pieces one night, searching. Torched a few nigger tents for the hell of it. He’s mad ’cause he was in town that night.”

“What night?”

“The night they escaped. I heard tell he decided to go whoring instead of taking the Murderess into custody as he shoulda. He tore through the tent city like the devil. ’Course, nothing came of it. The Major ain’t stupid.”

“You know him?” Kindle said.

“Nah, but I heard of him. Has a scar down the side of his face, said to be given to him by his brother in the war.”

“The Pinkerton go back East?”

“Can’t very well without his prisoner, now can he?”

I glanced at Kindle, whose expression was closed. Enloe pulled a plug of tobacco from his vest pocket. He tore off a chunk and chewed on it a bit, his gaze never wavering from us. He spit a brown stream into the fire. The spittle sizzled and a log fell. “Wouldya lookit?” He laughed up and down the scale again. “Kinda hot out for a fire.”

“Thought I’d make it easy for you to find us.”

“Didja now?”

“You’ve been shadowing us for three days. You aren’t as good as you think you are.”

“Well, I found you, didn’t I?”

“Oh, you weren’t the first,” Kindle said. Enloe’s smile slipped. “And, you won’t be the last.”

In a smooth, easy motion, Enloe leveled his gun at Kindle. “I seem to have caught you without your gun handy.”

“True. What made you come into Indian Territory? Alone.”

“Who said I’m alone?”

“My scout.”

“What scout?”

“The one who’s been shadowing you for three days. Where’s the Pinkerton?”

“I—”

I heard the tomahawk cut through the air the second before it cleaved Enloe’s skull cleanly down the middle. Blood ran crookedly down his scarred head, like a river cutting through a winding canyon. He tipped over onto his side.

I drank his whisky and watched him die.

Clutching the whisky bottle to my breast with my knotted fingers, I stared at the dead man while the words of my Hippocratic oath ran through my mind.

I will take care that they suffer no hurt or damage.

Little Stick, our Tonkawa scout, placed his foot on Enloe’s shoulder and pulled the ax from Enloe’s head with a sucking, wet squelch. The Indian threw the saddlebags across the fire to Kindle, who rifled through them searching for loot. I thought of my indignation with the Buffalo Soldiers looting after my wagon train was massacred, shook my head, and chuckled.

“What?” Kindle said.

Enloe’s dead eye stared accusingly at me. “Nothing.”

“Laura.” Kindle touched my shoulder, and despite myself, I flinched. He removed his hand. “He would have killed me and taken you.”

“Five men in seven days.” I turned to Kindle. “Did you know I’ve never lost five patients in my life?”

“No.”

“Here I sit, watching a man bleed to death and doing nothing. If my profession wasn’t lost to me because of this”—I lifted my disfigured hand—“it is because I have so thoroughly broken my oath, I cannot call myself a physician.”

“Oaths mean little on the frontier. Here it’s all about survival. Kill or be killed.”

“What a nihilistic life we will lead.”

“It’s better than being dead.”

I watched Little Stick rifle through Enloe’s person, searching for trinkets to trade or possibly give to his family as gifts. “His horse is good enough,” the Indian said. “We can trade him at the next camp we come to.”

“How much longer until we reach your tribe?” Kindle asked.

“Four days.”

I stiffened, the thought of hiding out in a camp of Indians no more reassuring to me seven days on than it was when Kindle told me.

After we escaped Jacksboro, Kindle and I rode hard all night and most of the next day, until we arrived at what remained of the ruined Army camp on the Red River. Six weeks had passed since the Comanche abducted me from the camp and killed all the soldiers escorting me to Fort Sill. With the influx of travelers for the trial of Big Tree and Satanta, the ruins had been scavenged until there was nothing left but a broken wagon and empty crates.

I had pulled my horse to an abrupt stop and stared at the wreckage. “We’re heading north?”

Kindle reined his horse back to me. He gave his horse his head and rested his hands on the saddle horn. “Northeast. To Independence, Missouri.”

I narrowed my eyes. “Through Indian Country?”

Kindle nodded slowly.

“No. Absolutely not.”

“Laura, I expect a dozen or more men left Jacksboro this morning, on our trail. The last place they expect us to go is through Indian Country.”

“It’s the last place I want to go.”

“Most will expect us to head to the railroad in Fort Worth. Sherman, maybe. A few will head south to Austin. But my picture will be all over the papers, and yours as well. Every railroad station in the state will be on high alert for us. The only direction that’s less likely than north is west, through the Comancheria.”

My head throbbed behind my eyes. “What’s in Independence?”

“Options. The railroad east or west. The Oregon Trail. The river to New Orleans. We can go wherever you want from there.”

“How are we going to get across Indian Country without being scalped or kidnapped?”

Little Stick emerged from the darkness, as if cued by a stage director.

“You cannot be serious.”

“We cannot do this alone, Laura. Little Stick will scout for us, ahead and behind. He will be with us little, only at night camp.”

I shook my head and looked away, trying to hide my tears of fear and frustration.

“Laura. We need another man, another gun, another person to take a watch at night.”

“I can shoot.”

“And very well. But, do you know how to speak Comanche? Cheyenne? Ute?” I shook my head. “Me, either. He will translate for us. He will be a modicum of protection from other Indians.”

“A modicum?”

“The Tonkawas don’t have many Indian friends these days.”

“Lovely.”

“He’s scouted for the Army for years. We can trust him.”

I sighed. “You can trust him. I’ll trust you.”

And, so here we were, seven days later, with five dead men and Little Stick grabbing the ankle of the last to drag him off to God only knew where.

“Wait.” I walked around the fire and removed Enloe’s eye patch. I washed the blood off with the leftover rotgut and handed it to Kindle.

“No one’s looking for a bearded Army officer with an eye patch.”

He stared at the bit of leather with distaste. “I suppose you’re right.”

I held the whisky out to Little Stick. He took it with a nod of thanks and set to his task.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “There isn’t enough for him to get drunk on.”

Kindle nodded, and with a half smile said, “You’re warming up to him.”

“No, I’m making sure he has no incentive to kill me, rape me, or turn me in. If a couple of sips of rotgut will buy another day of safety, I guess it’s a good bargain.” I took the eye patch from Kindle. “Here, let me.” He held the patch against his eye while I tied the leather strings behind his head. He adjusted it and said, “How do I look?”

With his salt-and-pepper week-old beard obscuring his scar, hat flattened hair, and face smudged with dirt, it was difficult to see the man I fell in love with. “Disreputable.”

He donned his hat and pulled it low. His one eye was barely discernible beneath the brim, waking the memory of a man staring at me across Lost Creek. I removed his hat. “Too much like your brother.”

Slowly, Kindle removed the bit of leather. His brother’s ghost descended like a curtain. John Kindle—or Cotter Black as he was known west of the Mississippi—couldn’t have separated us more completely if he was physically between us, grinning and laughing at how his plan to make me and his brother suffer had worked so perfectly.

Little Stick returned, holding a long, headless snake in his hand. “Dinner,” he said. The dead snake twisted and squirmed in the Tonkawa’s hand, and I tried not to vomit.

“Will it ever stop moving?”

Chunks of the skinned snake lay on a flat rock in the middle of the fire, twisting back and forth, though it was long dead and cooked through.

“When it gets to your stomach,” Kindle said. “Maybe.” Little Stick chuckled and bit into the piece he held.

I covered my mouth and pulled a piece of hardtack from my saddlebag. I longed for Maureen’s thick, savory Irish stew, for the warmth of our New York kitchen, for the sound of her humming her favorite tune as she worked, sometimes singing the Gaelic words softly to herself. I would stand in the hallway and listen, knowing she would stop as soon as I entered the kitchen, look up, and after a brief expression of irritation at being interrupted, her face would clear into a smile, and she would sing the stanza she made up for me.

I stared at the snake meat Kindle held, meat I’d skinned, gutted, and cooked while he’d taken care of the horses. Little Stick watched, giving me suggestions as my stiff fingers fumbled with squirming snake. My first human dissection came to mind: standing around a body as our professor cut into the dead man’s chest, the two male students next to me fainting, and the other students expecting me to follow. Instead, I stepped toward the body, kept my hands grasped lightly in front of me, and stared resolutely at the incision. The idea that six years later I would be using my surgical skills for my survival rather than another human being’s was absolutely unfathomable.

What a young, ignorant, innocent girl I had been. My experiences posing as a male orderly in the war had hardened me, but nothing prepared me for the West. The frontier had been an abstract, a myth of towering, noble men cutting a trail for civilization created by newspapermen to sell broadsheets, a dream of a better life dangled to poor farmers, the promise of a new start. A promise I bought into only too eagerly, a dream shattered on the banks of the Canadian River, and a myth crushed beneath brutality on a scale unimaginable in the civilized parlors of the East.

“Laura?”

I lifted my gaze to Kindle. “Hmm?”

“Are you sure you don’t want some? Cold camp the next two nights.”

“No, thank you.”

Little Stick finished off the whisky and tossed the bottle into the fire. “We will come to the forest soon. Better game. Less exposure.”

I closed my eyes and sighed. “Trees. How I’ve missed trees.”

From the waist down, Little Stick dressed as an Indian: deerskin pants, breechclout, and moccasins. Over his bare chest he wore a multicolored gentleman’s waistcoat that must have been splendid when new, but was now faded from exposure. The lines and swirls tattooed dark on his face were terrifying in the firelight. Strips of his long hair were braided with cloth and tied with metal trinkets and beads. My eyes were always drawn to the silver thimble on a thin strip of hair braided with yellow calico, and I couldn’t help wondering what woman had died so Little Stick could adorn his hair.

A mostly empty bandolier crossed his chest from left to right and he wore a Colt Walker on his left hip, gun handle pointing forward. An Army kepi embroidered with a horn rounded out his eclectic attire. He was dirty and stank and reminded me of things I longed to forget. But he showed a deference to me—almost a gentleness—I couldn’t understand and did not want.

As he did every night, Little Stick nodded to us, turned, and walked away from the camp. Kindle kicked dirt over the fire, extinguishing it, though a few embers peeked through. Bright stars speckled the moonless carpet of dark sky above us. I wondered if tonight would be the night Kindle would reach for me to quiet my growing worry that Cotter Black’s words had been prophetic.

Kindle sat next to me, close enough to feel his energy, though not close enough to touch. He smiled faintly. “Feeling okay?”

I nodded. Lying to Kindle was easiest when I didn’t speak. “Will they ever stop coming?”

“Eventually.”

“I should go back.”

“It is too late for that.”

“Five men, Kindle, dead because of me.”

“The world will not miss those five men.”

“Possibly.”

None of the dead men would have fit the stereotype of noble frontiersman the Eastern papers pushed. They were all cut from the same dirty mold, with a decided air of desperation hovering around the edges. I’d seen many more men of their ilk while in the West than honorable men. I sat next to one of the few of the latter.

I pulled my knees close and rested my forehead against them. I inhaled deeply, lay my cheek on my knees, and watched Kindle. He leaned back on one elbow, a leg extended toward the smoldering embers, the other bent and holding up his other arm. He rolled a twig of sage in his fingers, brought it to his nose, and inhaled deeply. He closed his eyes and smiled ever so slightly, his face relaxing from the tension of the trail into the countenance I knew so well from Fort Richardson.

He opened his eyes, glanced at me, and covered his embarrassment with a chuckle. He held out his hand and I leaned forward to sniff. The sage’s woodsy, slightly lemon scent brought a smile to my lips as well.

“Calming, isn’t it?” Kindle said.

“Yes.”

“Indians use it for cleansing ceremonies. They also use it for a variety of ailments. Mostly stomach troubles.”

“Do they? And how do you know so much about it?”

“I’ve spent almost six years in the West. You pick these things up.”

“What’s a cleansing ceremony?”

“Different tribes have different names and traditions, but they’re generally the same. When a boy is old enough, he is sent on a vision quest. He’s sent out into the wild alone to commune with the spirits, to get direction. Often times, a boy is given his adult name based on the vision received.”

“Is that how Little Stick got his name?”

Kindle laughed more heartily than he had in weeks. “No. He was given his name at birth and never outgrew it. It isn’t an exact translation.” Kindle raised his eyebrows and I understood.

“Heavens. Poor Little Stick.” I couldn’t repress a giggle.

“It hasn’t kept him from having two wives and six children.” Kindle waved away Little Stick’s inadequacies. “But, before a brave leaves on his quest, he’s cleansed in a sweat lodge ceremony.” He held out the sage branch. “That’s where the sage comes in.”

“Have you seen one?”

“No.” He scratched at his beard.

“Does it itch?”

“No, but I can’t seem to get out of the habit of scratching it.”

“Do you want me to shave you?” His eyes met mine, and I knew he remembered the night I had shaved him at Fort Richardson, how the world outside fell away. I longed to return to that moment, to do things differently, to make different decisions so we wouldn’t end up in Indian Country, a degraded woman and a disgraced Army officer.

“When we reach Independence.”

I reached out and touched Kindle’s hand. The jolt of electricity I’d felt when I shaved him was there, though faint, buried beneath shame and guilt. Kindle had given me so much and sacrificed everything to save me, and what had I done for him? The one thing I could do for him, he refused to consider. “I have ruined your career and your future. If we return, you could restore your good name, be dishonorably discharged.”

“My good name?” He laughed bitterly and pulled his hand away.

“Very few people know Cotter Black was your brother. Even so, no one will hold him against you, especially since you went after him.”

“There’s so much you don’t know about me, Laura.”

“There is nothing you could tell me that would make me think less of you.”

He met my gaze, and though I could barely see his eyes in the darkness, I could feel their intensity. “I wouldn’t be so sure.”

“Tell me.”

“No.”

“Don’t you trust me?” When he didn’t answer, I dropped my gaze. “I see.”

I stood and smoothed my blanket on the ground, folded it over for cushioning, and lay my head on my saddle, keeping my back to Kindle and the deadened fire. I tried to imagine myself in my bedroom in New York City, my head on a down pillow, sleeping under a blanket stitched together by Maureen. Outside, the lamplighters would be walking on their stilts, lighting the streets for the night. A heavy medical tome would sit on my bedside table, a bookmark saving my place for the next evening or whenever I had a chance to pick it up again. There could be a knock at the door any moment, with Maureen coming to tell me a servant was at the back door, asking for the doctor to come quick.

An owl hooted in the distance. I stared at the bank of the river. It could have easily been the riverbed where the Comanche stopped the first morning after they captured me. Where they spent hours raping and beating me, laughing and talking as they waited their turns. The memory was with me constantly, brought forth in a dozen ways. The sound of running water. The thunder of horses’ hooves. Laughing. Crying. Kindle’s grunt when he heaved a saddle on a horse. The clink of the trinkets in Little Stick’s hair. Little Stick. The stench of unwashed men. Kindle pulling away from my fingers lightly touching his hand.

I lived in a constant state of terror and despair, a scream of frustration always at the back of my throat wanting desperately to be free. I hugged myself to stop the shaking I knew would come despite the warm weather and the residual heat from the dying fire, as the longing for and revulsion of Kindle’s touch warred within me.

East of the Wichita Mountains the plains undulated and rolled off toward the forests and river valleys feeding the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. The swells and valleys of the small hills did little to break up the monotony of traveling across featureless plains with buffalo grass so tall it grazed our horses’ bellies. The constant motion of the buffalo grass, as well as the searing heat of the midday sun and the dry, hot wind blowing from the west, brought on a severe case of nausea. I could hardly remember a time in the last three months when I hadn’t been stricken with either nausea or a headache. I pulled my hat down low on my forehead, drank from my canteen, and kept my complaints to myself. Kindle could do nothing; there wasn’t a tree to rest under in sight.

“What is that song?” Kindle asked.

“Hmm?”

“The song you are humming? What is it?”

“It’s a song Maureen used to sing to me when I was a child. An Irish song. My earliest memory of her was her teaching me the song.”

“She raised you?”

“From the time I was five.. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...