Paul

Blood everywhere.

Slick across the bright white tiles of the bank’s floor, arced up the equally pristine wall behind him, a warm spray across his eyes. Paul Glenn’s boot sucked against the ground and left a perfect red impression of its sole as he staggered back a step. Screams and wails punctuated the air, the entire thing gone to shit in seconds.

“What now?” he screamed at his brother.

James Glenn’s eyes were wide and white, the only part of his face visible, the rest concealed by a thick black ski mask. But those eyes were wild with excitement more than shock. He looked pleased. Paul imagined his teeth bared in a manic grin behind the wool.

“Cops’ll be here in seconds,” Deanna McKeirnan said. “We gotta bounce. Right now.” Her face was tight with shock, hands trembling where she gripped her shotgun, but she remained stoic even as Paul felt his mind threatening to spiral away.

He stood halfway between the door and the body of the old bank guard who had tried to be a hero. Andrew, according to one of the staff who had yelled his name as James Glenn’s shotgun reduced his head to burger mince and blood. So much blood.

“We have to go!” Paul said, sobs threatening his voice.

“Not until we have the money, or what the fuck is all this for?” James spat. “Let’s move, get them to open the safe.”

Rick Dawson remained by the door, his eyes as white as James’s, shotgun at port arms. “He’s right, man.” His voice was level, calm, and Paul was glad of the support. Rick seemed the only one still his normal self. Something about that made Paul’s teeth itch.

Sirens wailed in the distance.

“We really fucked this up,” Deanna said. Kind of her to say ‘we’ when it had all been James. “Let’s go, try again another time. Or we’ll all go down.”

“FUCK!” James’s body vibrated, rock hard in frustration.

Bank customers cowered on the floor, some sobbed, one man’s grey pants had darkened with a wide spread of piss as he lay spattered with the guard’s blood and brains. A stark white shard of bone was caught in his hair. Must be the guard’s skull, Paul thought stupidly. Tellers and staff behind the glass had gone into shutdown, obviously someone already tripped the alarm. Paul looked left and right, his legs twitching with a barely suppressed urge to bolt. Should he run, leave them all and make a break for his own safety? No one will get hurt, James had said. The guns will scare everyone, we’ll take the cash and run. Small town banks have big money and little security. They’d driven for hours from western Sydney to this particular one, chosen after so much deliberation, if James were to be believed. He claimed he’d studied their position, size, number of customers, estimated their value.

And now it was all over in an instant, James’s shotgun barking murder. Paul tried to blink the guard’s blood from his eyes, his ski mask must be soaked in it. He’d been standing not three feet from the man, yelling at him to put down the gun. Outnumbered four to one, the old man had refused and James had stepped up to within a metre, levelled two barrels, and fired. Almost like he’d wanted to kill someone today more than he’d wanted the money. Paul derailed the thought when pictures of Imogen and the little boy rose in his mind’s eye. He couldn’t think about that now. But maybe… He looked at his brother’s wild eyes and cursed. Was all this a reaction to Imogen?

“Those sirens are getting nearer,” Deanna said, her voice iron hard. She stared at James with an intensity that made Paul’s skin crawl. He wanted so badly to run.

“Drop your weapons!”

They spun around. Two uniformed cops in the doorway, both with service pistols levelled, panning quickly left and right, trying to cover them all. Glock 22s, Paul thought dumbly. New South Wales Police carry Glock 22 pistols. He had no idea why or how he knew that. He froze. They must be street cops, just passing. Just lucky. Now they stood between him and freedom. Shit had turned to shitter. How could this day get any worse? Never think that, a tiny voice said in his mind, and he pushed it away.

Time slowed as Paul realised the police were watching him, James and Deanna. They hadn’t seen Rick yet, still by the door.

Rick, raising his shotgun, slowly like he was underwater. His eyes widening through the letterbox of his ski mask.

Paul’s mouth started to form the word “No!”

Someone on the floor yelled, “Beside you!”

Rick’s shotgun boomed and the nearest cop’s neck and shoulder exploded in blood and flesh, stark white bone suddenly, horrifyingly visible, as he jerked sideways into his partner. The first cop slumped, ragdoll dead, as his partner turned and fired. More screams punched the air, Rick Dawson grunted in pain and shock, one hand slapping to his gut as he sat down heavily, and James’s shotgun exploded again. The second cop flew backwards out the door, slamming into the pavement in a spray of blood. People outside flying away in a sudden frenzy, like a startled flock of birds.

“We’re out!” James yelled and ran, jumping over the dead cop and pulling open the door of their stolen car parked right outside. Deanna was behind him, but Rick struggled, had only managed to rise onto one knee, scarlet leaking between the fingers of the hand he pressed to his stomach.

“Fucker got me,” he said weakly.

Paul grabbed him around the back with his free arm and hauled him up. “Come on, man, come on!” Rick was a big guy, tall and heavy. It was some effort to move him. Paul’s guts were water, a sharp headache of panic speared between his eyes.

They stagger-ran out the door, Rick’s grunts of pain muffled through clenched teeth. The sirens were nearer, James yelling at them to Get in, get in!

Deanna, in the front passenger seat, leaned over and pushed open the back door. Paul drove Rick forward, into the seat, scrambled in behind him. James peeled out, Paul’s boot toes skipping against the asphalt as he nearly fell right back out again. Deanna grabbed his waistband over the back of the seat, Rick somehow held onto his arm, and he hauled himself in. The door slammed as James swerved the old dark blue Ford Fairlane sedan across honking oncoming traffic, through a red light, and away. Paul turned on one knee, looked out the back window. People ran back and forth. The cop outside lay in a widening pool of blood, stark against the pale grey footpath. But no police cars appeared as James swerved again, took a turn, and started putting buildings and distance between them and the debacle of a job that was supposed to be a cakewalk.

Leigh

Leigh Moore caught Rueben’s eye in the rear view mirror as she drove, rolled her eyes towards her husband, Grant, in the passenger seat. Her son smiled, shook his head. Such a grown-up gesture, her little boy a teenager now. How could he be thirteen? He had even started to look like a man, hints of adult physique showing through, a slight narrowing of the face, thickening of the shoulders. She missed her little boy so much, even while she was proud of the young man he was becoming.

“That joke wasn’t funny the first four hundred and nineteen times, Dad,” Rueben said, smirking.

“You people don’t understand good comedy,” Grant said. “Do they, Dad?”

Clay sat forward from his seat beside Rueben. “Son, I’m gonna be honest with you. As a dad, I think it’s my duty. You aren’t any good at the jokes.”

Grant barked a laugh. “That was your joke, Dad!”

“Yeah, and when I tell it, it’s funny. Stick to hotel management, son.”

“Says the retired hotel manager.”

Clay sat back. “I gave it all to you for a reason. Might be I’ll start up my comedy career any time now. Hey, I could do a Friday night slot in the bar once we open up!”

Leigh, Grant, and Rueben all made noises of amusement and horror.

“Gramps, I’ll admit you’re funnier than Dad, but you’re no comedian either.”

Clay mocked a hurt look as Grant said, “Hey!”

“Don’t miss the turn now,” Clay said, pointing.

The sign for the turnoff had become half overgrown with blue gum tree branches, but Leigh would know the way in the dark or fog or any other conditions, as would Grant. He’d been coming up here since he was born, when Clay ran the place with Molly. Leigh had been coming for the past eighteen years, since she and Grant had been together. Fifteen years since their marriage in the hotel they all called their home.

At least, their most-of-the-year home. “It’s not worth opening in the real winter,” Clay had explained decades before. “Too far from the snowfields for the ski tourism and not enough regular trade in the cold months to pay the bills. Better financial sense to take a break in the city.” Molly had never liked going back to the city, but she did it for Clay. And Grant had enjoyed it as a kid too. Now it was valuable for Rueben to spend some time away from the hotel.

But so quickly the time passed. Perhaps it was Molly’s death that made Leigh maudlin, the first time back since Clay’s wife fell to breast cancer six months before. But they were all young and hale, even Clay himself a powerful seventy-one years old. Like the trees they drove past he still stood strong, even if he did complain a lot about his arthritic hip. She couldn’t ever imagine him going, but she’d felt the same way about her mother-in-law, and how quickly that had changed. She chanced a glance at Grant, wondering again how he was really coping with his mother’s death. Like his father. Clay and Grant were equally closed books emotionally.

She made the turn and started up a narrower road, the journey into the deeper bush starting to take shape. Still more than another hour to go, but it always felt like the home stretch when they left the highway behind not far from Enden and headed up into the steep hills of the National Park.

Rueben keyed his walkie-talkie. “Hey, Uncle Simon, you copy.”

“Go ahead, Nephew One.”

Leigh smiled. Her brother and Marcus might be childless, but they were great with her son. They would make great dads one day, perhaps. She’d asked once if they planned that and Simon had been circumspect. She thought perhaps he was keen, but Marcus maybe needed convincing. She wouldn’t interfere, it was their business. Regardless, she hoped.

“Who’s funnier, Dad or Gramps?”

“Well, that’s a tough one, champ.” Simon made some noises of thought.

Leigh glanced up in the mirror as a curve in the road started to obscure the highway and saw Simon’s bronze Toyota turn in and follow them up the hill. She could just make out Marcus behind the wheel, Simon holding the walkie talkie in front of his mouth.

“You know, it’s like asking which is tastier, cabbage or broccoli,” Simon said, his voice tinny over the small speaker. “I mean, they aren’t either a good steak or a tasty donut, you know what I mean?”

Rueben laughed and Clay and Grant both made noises of outrage.

“He does have a good point,” Leigh said, grinning at her husband. Grant just shook his head.

“Maybe don’t distract those two back there,” Clay said. “Maybe they’ll take a wrong turn.”

“They’re right behind us and it’s one road all the way now!” Leigh said. “Besides, they’ve both been coming up here almost as long as us.”

“Yeah, but your brother is easily distracted.” Clay smiled at her, waiting for the baited hook to catch.

Leigh shook her head. “Enough, Clay. Remember how we just established you’re not funny? Leave him alone.” One slip-up, years ago, and Clay wouldn’t let it go. Rueben was right, the old man was no comedian, if for no other reason than he never updated his jokes. The ones he had were all as old and rusty as garden tools left in the rain. It was kind of endearing, in its own infuriating way, but it was still infuriating. “Besides, Marcus is driving.”

“Simon left that hose running one time,” Grant said, and Leigh was grateful for his support. “The water damage wasn’t even that bad.”

“The tank was empty though, and it took half a season to refill.”

“And Simon hardly showered for a month in contrition!” Leigh said.

“I remember the smell,” Grant said. “You all remember? Oh man, we made sure he did all the outside work that season.”

Clay grinned and sat back into the seat. Leigh shook her head, but couldn’t suppress a smile. Smug bastard, he loved to stir for no reason other than the sport of it. But he never bullied, she reflected. She was grateful for that. It was an important distinction. Rueben had been dealing with bullies and it was a contributing factor to him being home-schooled, though the main reason would always be their divided life. Spending most of the year at the hotel, remote from anything, made accessing an education difficult. Rueben seemed to be dealing with it well, but Leigh struggled with the guilt of his isolation. It was on them, her and Grant, that Rueben’s life was so far removed from that of most kids. He spent almost his whole life in the company of this same small band of adults, and the constantly revolving sets of guests. Still, a lot of them brought kids along and Rueben assured them he loved the life. She needed to talk to Grant about it again. Rueben needed to spend more time among his peers, especially now. He wasn’t a kid any more, things changed. She and Grant had argued about it again and again, but her husband refused to be swayed. Roo should be at high school, surrounded by teens like himself. But then there was the bullying. She shook her head, once again lost for a good answer.

The car sank into a silence, the whirr of tyres on asphalt and a gentle hum from the engine the only sounds. The four of them could never agree on what music to play, so no music was the democratic decision. Leigh appreciated the meditative result. It was good to spend time with only your thoughts, healthy for the mind. She hoped the others got the same benefit, whether they realised it or not.

The road climbed, the trees becoming greener as winter slowly gave up its grip begrudgingly to spring. Green leaf and bud would start to burst forth within the next few weeks, hikers and fishers would arrive. The Hotel did a good trade in walking and fishing tourists. Eagle Hotel was a family-friendly, holiday-oriented place. They got a lot of couples looking for romantic getaways in “the most remote hotel in New South Wales.” A bold, and largely spurious claim. Several places around the state tried to hold the title for themselves, and it was a blatant lie, probably for most of them. But Leigh was comfortable enough with the tag line. They were definitely in the top ten. Maybe.

“Hey, Nephew One, copy.”

“I hear you, Uncle Si.”

“Marcus said he wants to teach you to make proper Chinese spring rolls this year.”

Marcus’s voice came over. “My old Grandma Cheng taught me and I want to teach you. That okay?”

Rueben looked up, caught Leigh’s eye in the mirror and grinned. “Sure thing!” he said into the walkie-talkie. “But why now?”

“I’ve been trying to get that recipe out of him for years!” Leigh said.

“Marcus said he just wants to piss off my sister,” Simon said.

“Hey!” Marcus’s voice was muffled and there was a scuffling sound, then his voice came over stronger. “Leigh, I know you want my recipe, but I gave you most of my stuff already. And you watch me cook at the hotel all the time. Roo, this is something special, my gift to you, okay? I wanna make sure someone has it for the next generation, and I want you to have something special from my grandma. That’s how we do things.”

“Give me that back.” Simon’s voice came back clearer. “So yeah, that and it’ll piss off my sister. That’s okay, right, champ?”

“Everyone’s happy!” Rueben said with a laugh, reaching forward to squeeze his mum’s shoulder. Leigh shook her head.

“And I’m going to teach you how to fix the engine in that old truck up there,” Simon said. “You want to learn about motors?”

“Hell, yeah!”

“It’s all home schooling, right, Sis?”

Rueben reached through from the back, his thumb depressed on the talk button. “Yes, I suppose it is,” Leigh said into the walkie. “Now you both concentrate on driving, we don’t want any accidents in the last few kilometres.”

“Check, check, over and out, rubber duck, ten-four!”

Rueben pulled the walkie-talkie back. “Uncle Si, cut it out! You sound old when you do that.”

“Holy crap, really? I don’t want to sound like your dad!”

“Hey!” Grant barked.

“You people are all crazy,” Clay said.

“Signing off,” Rueben said, and pocketed the walkie-talkie. He leaned forward between the seats. “I’m hungry.”

“All that talk of spring rolls. We’re out of snacks, sweetie. The rest of the supplies are in the trailer with Simon and Marcus, so you’ll have to wait.”

“We could pull over.”

Leigh laughed. “We’re only half an hour away. I know you have a metabolism like a race car right now, but you’ll live.”

“Sure, fine. I’ll just waste away back here.”

He slumped back into his seat, but gave her a crooked grin in the mirror. She caught sight of Clay digging in his jacket pocket and he slipped Rueben something. Her son’s eyes brightened and he shared a quick hushed conversation with his grandfather, then started into the candy bar the old man had given him. Leigh pretended not to notice, her heart warm at the closeness Clay and Rueben shared. She and Grant got on well with their son for the most part even if they did have their own differences, but Clay had a special connection with his grandson. He had since the boy was born, some spark secret to them that she and Grant would never really understand, let alone share. Part of her was jealous of it, but a larger part remained happy. For all his life among adults instead of others his own age, he had something there with Clay most kids would never know.

She realised with all the chatter that she’d driven right by the Hickman’s place, and silently cursed. She’d meant to swing in and let them know the family was back, as she’d forgotten to call before they left. The Hickmans always watched the place in the off-season, as much as the weather would allow at least. Never mind, she’d call them later, or maybe in the morning. There was no rush.

Before long the sign for the hotel appeared, the 2 km marker. Grant made sure everyone had noticed before drawing a deep breath.

“Dad, come on,” Rueben said.

“Two kilometres, why is it so far?” Grant asked proudly.

“Every damn time.” Rueben looked at Clay. “You used to do this to him, right? This is called the cycle of abuse.”

“Yeah, but like I said, it was funny when I did it.”

Grant laughed along with them. “It really wasn’t, Dad. Even I’ll admit that’s never funny after a drive this long.”

Minutes later Leigh turned in through the carved gates of the hotel and up a long winding, well-maintained dirt driveway. As the hotel came into view, a strange sensation settled in her stomach. The excitement of coming back was there as she’d expected, but something else too. Something greasy and disquieting squirmed inside her. The tyres crunched on gravel as they drove into the grounds proper.

Leigh smiled despite the mild discomfort. The sight of Eagle Hotel always warmed her. It stood tall and proud, surrounded by bush on all sides, the centre a double-height atrium lounge room with wide verandas front and back, the steep gabled roof pointing into the slate cloudy sky. Either side, two stories stretched out like arms with perpendicular roofs, on the right the fourteen guest rooms, six below, eight above, each with their own bathroom. On the left, the large dining room and kitchen on the ground level with the Moore family private quarters above. Simon and Marcus stayed in the small single-bedroom guest cottage across the driveway from the kitchen, backed up into the gum trees there. It was a good arrangement.

The hotel was dark, but at first glance seemed to have weathered the winter well, no obvious signs of damage. A full inspection would be the first job after they’d eaten. The weathered wooden walls, dark tiled roofs, windows each with a small gable of their own, seemed warm despite the obvious lack of occupancy. That was familiarity at work, she knew. Once they’d got the heating on and the lights on and the fireplaces blazing, the place would be like a giant house-shaped hug in the wilderness. If only Leigh could shake off the sudden concern, inexplicable but present, that sat in her gut.

She drove between the hotel and the small guest cottage, crunching across gravel to park in the space behind the kitchen, in front of a huge triple garage of wooden weatherboard and shingled roof. Simon and Marcus had caught up and pulled in right behind them. They’d put the cars into the garages after unloading the trailers, and then Grant would fire up the old pick-up and head an hour and a bit back the way they’d come for more supplies in Enden once a quick assessment had been done. Then a couple of weeks of airing out and fixing damage before the handful of local staff arrived, and guests soon after that.

As the six of them emerged from the cars and stretched, breath clouding in the frosty air, smiling at each other, Leigh said, “Simon, just grab the green bag for now. We can all have a late lunch first, then get to work.”

“I’ll get it,” Marcus said, and leaned back into the Toyota.

Leigh unlocked the back door and they went into the huge kitchen, smells of metal and polish, dust and cold, plus the indefinable familiar scent of the hotel, wrapping them up immediately.

“I’ll get some sandwiches made,” Leigh said. “Roo, will you wash out the pot and get some coffee on? Run the water first, check it comes clean from the tanks. Your dad can check the bore later.”

“Sure, Mum. And when we’ve eaten I want to go and check out the tree house, okay?”

“You can help us unload the cars first.”

“Awwww, Mum…”

Before she could insist, Grant put a hand on her shoulder. “The lad’s been cooped up in the car for hours. He’s too young for that. Let him go run and exercise. We can manage the unloading.”

Rueben whooped and ran across the kitchen to the coffee pot.

“You’re too soft on him,” Leigh said.

Grant kissed her cheek. “Sure, I’m the softie.”

“Go and turn the water and power on.”

“Sure.”

“Stop the canoodling and get with the sandwich-making!” Clay said. “I’m too old to wait this long for lunch. I might keel over dead while you two neck.”

Leigh smiled, taking bread from the bag. “Calm your farm, Clay. No one’s dying today.”

Clay

“You okay, old sword?”

Clay smiled. Only Molly ever called him that, had since they first met. That party a lifetime ago and he’d seen the brunette beauty in the gingham dress and said hi, asked her name.

I’m Molly Taylor. You?

Clarence Moore, but my friends call me Clay.

She’d laughed, high and fresh. Claymore? Like the Scottish sword?

I guess. He hadn’t known what she was talking about, but looked it up later.

There she stood in the Eagle Hotel kitchen, near the door to the big dining room, hands on her hips, head tilted like always when she was about to dispense some wisdom whether you liked it or not. Clay smiled, stood up to stroll toward her.

“I’m gonna stretch my legs, look over the downstairs,” he said.

Leigh didn’t turn around from the counter. “I’ll holler when lunch is ready.”

Clay walked past Molly, heard Grant banging around in the utility room as he passed the door. He strolled through into the dining room. It was still and dark, curtains all drawn, chairs upended on tables. It smelled dusty. He began pulling open the curtains, flooding the big space with wan late-winter light, automatically checking for signs of leaks, broken glass, like he had so many times before. The winter in the mountains could be harsh.

“I’m okay,” he said softly. He knew she wasn’t really there, but he had the sight. He saw… things. She’d had it too, in life. It had cemented their relationship.

“You are not okay, my love. You could rarely lie to me before. You sure as hell can’t now.”

Clay laughed, reaching for another curtain, then winced. He put a hand to his hip. Damn his aging body, the vagaries of time. His mind remained young and vibrant, his desires and dreams lived on, but there was a hole in his life where Molly had been, and a dozen aches and pains permanently reminding him he probably wasn’t far behind her. “I miss you, is all.”

“And?”

He turned to her. How he wanted to hold her, feel her, smell her, again. Tears filled his lower lids. “I do miss you so.”

“I know. I miss you too. But you’re scared of something else.”

“You gonna make me say it?”

She smiled at him, head tilted again. She had aged so well, fine features, brunette turned iron grey, still formidable. He was pleased she appeared this way, not like at the end, when breast cancer had reduced her to bones and tears.

“Dammit, woman.” He grinned, but his insides were ice water, had been since they’d pulled in and he’d seen the old place again. The first time without her. “We took such a risk buying this place.”

“But we made it wonderful.”

“And now you’re gone.”

“But you’re still here.”

Clay shook his head. “I’m not enough.”

“You’ve always been enough. More than enough.”

“It was you, Molly. Always you. You’re the strength.”

She smiled. “My sweet, sharp sword. You know better.”

“I’m scared it’ll happen again.”

“How can it? That was then, one horrible time, and we sent him away.”

“But he might come back.”

“He hasn’t for what? Fifty years? He’s gone, I promise.”

Clay nodded, stared at the floor. He was gone, true. But Clay had always feared the thing that night was a symptom, not the cause. With Molly around, he felt he had a way to fight anything that might come along. With her gone, he felt vulnerable. Alone.

“It’s been half a century, old sword. You just miss me, that’s all. Don’t try to make it about something else.”

He sighed, wandered through the dining room, past the stairs leading up to the family’s private quarters, the door closed at the top. He stared into the empty, cold stones of the massive dining room hearth. “It was bad.”

She stood at his shoulder, so close, but an infinity away. “Yes. It was bad. But we fixed it no problem, remember? We finished it, easily enough in the end, and completely.”

He walked past the hearth, through the wide double doors into the huge, high-ceilinged main lounge. The counterpart of the dining hearth stood equally cold and dark on this side. Sheets like ghosts lay over all the couches and armchairs. Photographs of the area, historical and modern, adorned the walls, fans hung inert from the dark wooden cross beams high above. Two wood columns, each some two feet square, evenly spaced in the centre of the room, added structural strength to the high, wide atrium roof. Clay stared up between them, remembering a night with terrible shadows. He shook himself. Molly was right, he’d lived here almost fifty seasons since with not a care. Maybe it was just grief.

Light poured in through tall gable windows above the small box of the reception office at the front, where the main doors led in. He pulled open the curtains below them, next to the office, revealing sliding doors that let out onto the large front veranda. They’d remove all the covers, open the doors and windows, go into the other wing and air out all the bedrooms soon enough. Maybe it would seem less daunting when it was freshened, warmed. When it had emerged from its winter stasis to be a home again. A welcoming hotel. Ready for people. He dimly registered the green exit signs lighting up as Grant put the power on.

He went to the bar along the back wall of the big room, sat on one of the stools in front of dark, polished wood. His eyes fell, as they always did, on a large black and white photo. He and Molly so young, so long ago, when they had opened that first day. A brass plaque underneath read Clay and Molly Moore welcome you to Eagle Hotel. Nearly fifty years ago. They were so very young, and already they’d endured so much. And beaten it. They were valiant, invincible, eternal. Now an invisible corruption of cells had taken Molly away, and time itself ate his bones.

“What do I do, Molly? If something starts again?”

“It won’t.”

“You’re not here. And Grant’s never had the sight, he can’t help.”

“Perhaps you should call Cindy if you’re so concerned?”

Clay smiled sadly, shook his head. “Grant’s sister has the sight and could help, but she still won’t admit it.”

“She came when I was sick. And to my funeral.”

“Yes. But she won’t come here, you know that. Never here again. She hated the hotel, the home-schooling. She felt the history of this place. What happened even before we came. Even though it was so long before she was born.”

Molly nodded, looked at the ground. “She always said this place was bad.”

“We tried to prove to her it was fine.”

“I wish we could have found some common ground with her over that.”

Clay nodded. “Our daughter will talk to me occasionally on the phone, but that’s all.”

“Even now I’m gone?”

Clay laughed softly. “I think perhaps we’re more estranged now you’re gone.”

“I talk to her sometimes, but she pretends she can’t hear me. Can’t see me.”

“I guess I’m not surprised.”

Molly sat on the stool beside him, reached out one hand that could never touch him. “Maybe Rueben…”

“I hope so. It sometimes skips a generation, you said. Never two?”

“I wouldn’t say never, but I only ever heard of it skipping one. It missed Grant, but not Cindy, so who knows. Rueben’s around the right age.”

“I’ve been watching. Haven’t seen anything yet.”

Molly nodded softly. “Me too. But soon, I’m sure. He’ll need your guidance.”

Clay shook his head. “Even so, the boy is thirteen. Too young for that kind of responsibility. Too young to fight.”

Molly smiled. “We weren’t so much older. And you won’t have to fight again, no more than we ever did in the years since. Keep the love in sight, be here for each other. The hotel is okay now, has been since before Grant was born. You just miss me, is all. And I miss you too, old sword.”

“It was you who kept the peace here, Moll. I don’t know if I can do it. I tried so hard to convince Grant and Leigh to sell up after you…” He swallowed.

“Died. Say it, my love.”

He nodded, breath stuck behind the grief in his throat. Tears trickled over his wrinkled cheeks. At last he gasped in. “After you died,” he said, the words bitter. “But they wouldn’t listen. They put it down to grief.”

“They’ve been building a life here for a long time now. They plan to go on with that, like we did. And they will. They’ll be okay. One day Rueben will run this place.”

“I hope you’re right.” He looked up, saw her smile, and his heart cleaved again. “I miss you so much, my Molly.”

“I love you.”

“Clay! Lunch!” Leigh’s voice bounced through the big rooms and Clay startled, glanced back over his shoulder.

When he turned back, Molly was gone. If she’d ever been there. Was he really talking to her ghost? Or her memory? Was there even a difference? The sight could be opaque sometimes, despite its clarity. One of the many dichotomies of life.

“Coming!” he called out, and slipped off the stool, wincing again at the deep pain in his hip and an accompanying stab in his knee. “God damn this aging carcass.”

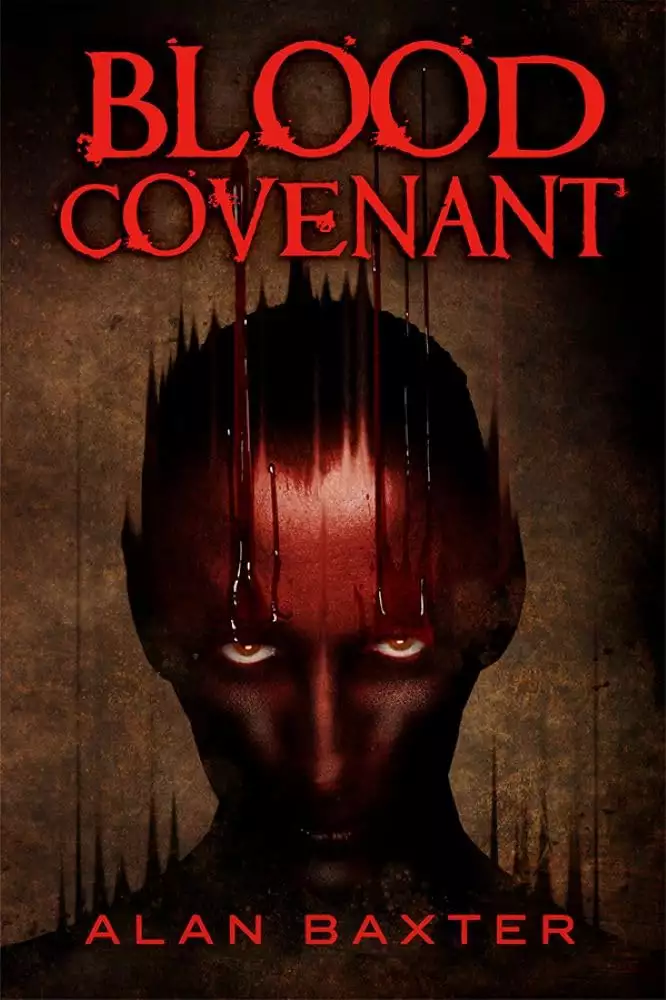

(c) Alan Baxter 2024