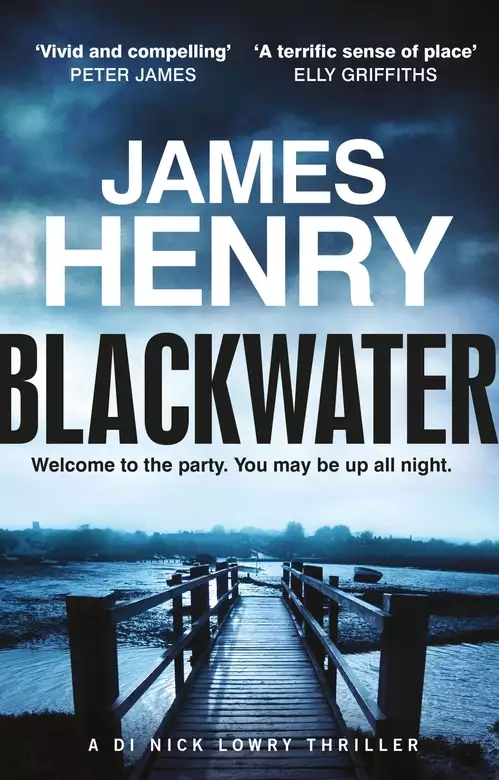

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

'A fast-moving thriller. I was totally absorbed by it' ELLY GRIFFITHS

'Vivid and compelling, with great evocation of the 1980s period' PETER JAMES

'A masterclass in place and landscape' CHRISTIE WATSON

January 1983, Blackwater Estuary

A new year brings a new danger to the Essex shoreline. An illicit shipment, bound for Colchester - 100 kilograms of powder that will frantically accelerate tensions in the historic town, and leave its own murderous trace.

Detective Inspector Nick Lowry, and his fellow officers Daniel Kenton and Jane Gabriel must now develop a tolerance to one another, and show their own substance, to save Britain's oldest settlement from a new, unsettling enemy.

PERFECT FOR FANS OF PETER JAMES AND STUART MACBRIDE.

Release date: July 14, 2016

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blackwater

James Henry

10.45 p.m., Friday, New Year’s Eve, 31st December, 1982 Blackwater Estuary, Essex

Though they couldn’t have been travelling at more than six knots, the din when they unexpectedly beached the boat was horrific. The older man’s panic subsided once the racket of the small outboard motor was silenced and he realized they weren’t going to sink; that they had in fact run aground. Now all was quiet. And eerily dark.

‘Jesus, weren’t expecting that,’ his younger companion said, shaken.

Boyd grunted. He flashed the torch uncertainly around them. He couldn’t see a thing in this fog. The boat gave unsteadily as he moved to the stern, water lapping gently at the hull. They must have hit a sandbank.

‘Right, Felix, you go first,’ he said. The boat rocked as his companion hauled one of the two rucksacks on to his back.

The late-night tide, being a high one, must have drained quickly, as if a plug had been pulled. He sensed they were far from their planned destination and cursed quietly. He should have known the boat was too small to hold its own against a strong ebb tide. They had been travelling for what felt like hours; a more powerful engine would have had them here quicker, before the tide had run. But where was ‘here’, exactly? There were no lights visible on the shore. He had thought originally the foul weather would give them extra cover under which to land, but he had not foreseen the possibility of getting lost.

‘You comin’, Jace?’ Felix called, already ashore and invisible in the icy darkness, though he couldn’t have been more than a few feet away.

Boyd hauled the second army rucksack on to his back, making the waist straps secure, almost toppling with the weight. He let out a groan. Fifty kilos was, unsurprisingly, fifty kilos.

‘Come on!’ Felix called again, his footsteps crunching over what must be oyster shells.

‘Right, here goes.’ He drew in a breath that was pure sea mist before clambering off the tender and – Christ! – into freezing-cold water up to his waist. The boat had swung with the tide and he’d misjudged which side to jump. The sudden ice-chill caused a wave of panic; he waded desperately towards his companion’s torch, fearing for his cargo, which, though vacuum-packed, he couldn’t risk getting damp.

‘Fucking ’ell, mate! What you doin’, garn swimmin’?’ The small torch beam bounced erratically in his direction.

‘Piss off!’ Boyd spat breathlessly, infuriated at the piercing cold numbing his groin. Regaining his composure, he looked desperately around him, but could see nothing. ‘Where the fuck . . . ?’ he muttered. Turning to the right, he could just make out faint lights twinkling in the mist, like dimmed Christmas-tree lights, but that was . . . too far away? He’d anticipated lights to the west, not to the east. This wasn’t good – they must be way off course. He reached into his snorkel-jacket pocket for the compass, his numb fingers unable to differentiate the various objects: lighter, knife, keys – there, he had it. But he’d left his torch behind. Fuck. It was only a torch, though, and he wasn’t going back.

‘Give me that!’ he snapped quietly, though the caution was unnecessary – he could have screamed and nobody would have heard. He flashed the torch beam on the compass, the sudden brightness off the glass hurting his eyes and causing him to blink rapidly. ‘Brightlingsea? Must be . . .’

‘We lost, skipper?’ He felt his accomplice’s warm breath at his ear.

‘No. Just further east than I thought. And very, very late. The tide must have carried us. Poxy boat. We’re off East Mersea – on the mudflats, at least half a mile from the beach and two miles east of where we should be. We haven’t a hope of making the meet tonight – or seeing anyone else, for that matter.’ He turned sharply, directing the torch into the young man’s brown eyes, the pupils shrinking in alarm. ‘There’s only you, me and one hundred kilos of high-class party powder.’

-1-

1 a.m., Saturday, Colchester CID, Queen Street

The telephone’s sudden ring jolted DI Nick Lowry awake and he knocked over a mug of coffee. Lowry, thirty-nine, ex-Divisional athletic and boxing champion, was too big for the 1950s wooden desk he’d slumped asleep on, and he started as the cold liquid reached his prone elbow. Realizing where he was, he yawned and scratched his dark brown hair, glancing sheepishly at his younger colleague, opposite, who was scribbling notes under a grimy Anglepoise lamp.

The telephone had stopped ringing. He checked his watch. He was late. Very late. He’d been expecting a call from his in-laws – hours ago – to summon him to collect his son from their house. They’d taken him to a panto in London starring Rod Hull and Emu. He’d told them he’d be working late so they should call him at Queen Street once they got back to their place in Lexden. Perhaps that had been them on the phone – but why so late? Traffic, snow, accident – the possibilities raced through his mind in ascending order of potential danger and parental panic rose in his throat. Shit, why did he have to nod off!

‘Made a mess there,’ DC Daniel Kenton tutted, without looking up from his paperwork, his glasses sliding precariously close to the edge of his nose. Kenton was twenty-five and far too young to be wearing specs that made him look quite so studious. University educated, Kenton was considered to be exactly what the force needed in the modern age, according to Essex County HQ. And, though County’s dictate on progress was not always Colchester Chief Superintendent Sparks’s view on progress, in young Kenton they did in fact meet, for Kenton could box, and box well. Not that you’d guess it to look at CID’s most recent recruit. He flicked back his too-long foppish hair in a vaguely feminine way; Lowry thought him too big a lad to carry it off. Kenton probably thought it made him look intellectual.

‘What were you doing, letting me doze off like that?’ Lowry yawned, shuddering involuntarily in the cold of the Victorian building. ‘What’s happened to Matthew? I should’ve heard from him ages ago!’

‘Don’t panic. Your son is in Lexden with your wife’s parents. The night sergeant took the message. They’ve only just got back. Fog on the A12.’

Lowry grunted with relief. ‘What are you even doing here at this time of night? No New Year’s Eve parties for you?’

Kenton looked up from his writing, taking off his glasses to reveal handsome, boyish features. ‘No. Making the most of it now things appear to have quietened down, so I’m getting the paperwork on the Mersea post-office job out of the way.’

‘Right, well, no point me hanging around here,’ said Lowry flatly, getting up. Just then, the phone started to ring again.

Kenton was meticulously fitting the cap on what Lowry knew to be an expensive fountain pen – a graduation present. ‘Aren’t you going to answer that?’ he said. ‘The night sergeant knows you’re still here. It can’t be anything as bad as last night.’

Lowry glanced at the obstinate phone vibrating on the desk. Not the in-laws, then. His mind flickered back momentarily to the violence of the previous evening. He snapped up the receiver, glaring at the satisfied Kenton as he did so. ‘Lowry.’

‘At last,’ the night sergeant replied. The line was terrible, as though there lay a continent between them instead of a single storey. He could only make out the last word: ‘ . . . body.’

‘Beg pardon?’ Instinctively, he reached for his cigarettes, forgetting he’d given up as of now.

‘A car’s run over a body. The vehicle was travelling at speed. On the Strood.’ This was the local name for the causeway between the mainland and Mersea, an island that lay seven miles to the south of Colchester. It was often hit by high tides, which could cut the five-thousand-strong populace off from the mainland for up to three hours at a time. ‘Wait, why are you calling me?’ Lowry asked. ‘Get the Dodger’s boys out. They can handle an RTA, surely . . . I know it’s late, but still.’

‘The Mersea lads are on it, but this ain’t no RTA – the body is lying in six inches of water. It’s missing its head. And an arm.’

Lowry swallowed hard. ‘The body’s headless?’ Kenton caught his eye.

‘Yep, shaved clean off . . .’

Lowry hung up.

‘Problem?’ Kenton asked disingenuously.

1.10 a.m., Colchester General Hospital, Lexden Road

Jacqui wriggled on the bed and hoicked down her uniform. The mattress let out a sigh, signalling her lover’s imminent departure. The lights remained off. She swung round and felt with her toes on the cold, tiled floor for her shoes; the room was pitch black. She could just make out the luminous marks on her Timex watch. Her break was nearly at an end – she’d have to make for the nurses’ station straight away, no time for a cigarette. She heard the distinctive sound of his trouser zip, always the final step after realigning his shirt and tie.

‘One day we’ll have to try it with the lights on.’ She laughed quietly. But there was no response – instead, a vertical slash of light appeared as the door to the private room opened.

‘Got to go. Bleeper,’ came a whisper from the darkness, and without a pause his slender frame slipped through the crack in the door.

‘Of course. Saved by the bleeper,’ she muttered to herself. She knew what they were doing was risky, but it was still curiously convenient how the bleeper always seemed to go off as soon as they’d finished. She sighed and slid off the bed.

Reclipping her hair hurriedly, she crept out into the green-lit corridor, closing the door softly behind her. She padded along and turned into the dark hospital ward, her heart racing as the thrill of what she had just done resurfaced amid the sterile normality. She stopped short of the light of the nurses’ station to adjust her tights.

‘Jacqueline,’ an authoritative voice barked behind her, causing her to jump. She turned and saw the dour, familiar face of the ward sister.

‘Yes, sister?’ she replied demurely. The sight of her brought her up cold. She fiddled nervously with her wedding ring.

‘Where have you . . . ? Never mind. Private Daley is in Resuscitation.’

One of the young soldiers.

‘Cardiac arrest,’ the sister added. ‘You are needed there.’

Jacqui turned to leave.

‘Nurse, your tunic,’ said the ward sister.

Jacqui adjusted her uniform, feeling herself flush and hoping that the ward sister wouldn’t have spotted it in the low light. The other nurse on duty looked up knowingly from the station desk. Jacqui ignored the smirk forming on her lips.

The sister turned on her heels and marched off at a clip. Jacqui refocused her mind and recalled the injured young soldier admitted during the hectic hours of the previous night. He seemed little more than a boy; she’d almost laughed when she heard he was a soldier. He was nineteen, apparently, but lying there unconscious in a nightgown, bum fluff on his soft cheeks, he looked barely out of puberty. The boy was now in the best possible hands, the very same hands that, only minutes earlier, with a different sense of urgency, had pinned her to a hospital bed. At least, she thought, hurrying past the ward sister towards her patient, Paul had a genuine call this time.

-2-

1.15 a.m., Saturday, The Strood, Mersea Island side

The Land Rover groaned to a halt, throwing Jason Boyd’s unbelted accomplice towards the dashboard with an unpleasant crunch. Ten feet in front of them was a police vehicle, a jam-sandwich Cortina, parked side on where the Strood road met the East Mersea road. Visibility was almost nil, and Boyd hadn’t seen the other car until they were practically on top of its languidly rotating blue light. He threw the vehicle rapidly into reverse and backed up to a respectable distance.

‘Fuck!’ he said under his breath. Fog or no fog, he should have seen the blue light.

‘Nearly cracked me head open,’ Felix moaned, rubbing his forehead.

‘Well, you should belt up, then,’ Boyd retorted unsympathetically. ‘Clunk click and all that bollocks.’ The fluorescent police tape was now just visible, floating in the mist before them. But not much else. Beyond the police car the thick night made the causeway invisible.

‘This is all we need,’ Boyd sighed, lighting a cigarette.

‘Nuisance,’ Felix added.

‘Nuisance? Contact with the Old Bill? More than a nuisance, you plum.’ He shook his head in the dark cab.

‘Where’s the panic, Jace? We just say we’re trying to get home across the Strood . . .’

‘Er, yeah, mate; with what we’re carrying, we better bloody hope so. Maybe the smell of us will put him off hanging around.’

Boyd fidgeted uncomfortably in his mud-covered jeans, now beginning to dry but itching like hell. After trekking across the mudflats for what must have been two miles, they were exhausted; even with a map, it took an age to find their Land Rover in the pitch-black winter. The plan was to land under cover of darkness around six, and be in Colchester by seven; even if they’d got ashore on time, he’d still not allowed enough time for walking by foot – if they ever did this again, the whole approach would need a rethink.

The Land Rover’s ancient idling diesel engine stuttered suddenly, as if choking on the wet, prompting a uniformed officer to materialize out of the gloom.

‘Fuck! He’s coming over!’ Felix exclaimed.

‘Well, just say we’ve been bait-digging, and then stopped off in the pub,’ Boyd said, half wondering if it was worth a try if they were questioned.

There was a rap on the glass. Boyd wound the window down and smiled. A torch beam scanned the cab and settled on Boyd’s face. ‘Happy New Year, officer. Problems?’ he asked, squinting in the light.

‘I’m afraid I have to tell you to turn back.’ The policeman, young and thin-faced, looked chilled to the bone. ‘There’s been a fatality.’

‘Not surprised, in this weather,’ Felix replied.

‘Where are you boys heading this time of night?’ the officer asked.

‘Colchester,’ Boyd answered coolly. ‘We’re just on our way home. We’re not from Mersea.’

‘We’ve been bait-digging,’ Felix said.

Boyd cringed and added quickly, ‘We stopped at the pub, just to warm up, like, before heading off.’

‘Which one?’

Luckily Boyd remembered passing the pub. ‘The Dog and Pheasant . . . we only had the one.’

‘Sure, sure. Need to warm up on a night like this. Well, go back there and knock up old Bob, and he’ll let you stay the night. Say there’s been an incident and the only way off the island is shut.’

‘Thank you, officer,’ Boyd wound up the window hurriedly. ‘Friendly for a copper? Makes a change. That’s that, then,’ he said to Felix. ‘Well, we can’t hang around here drawing attention to ourselves. There’s nothing for it. To the Dog and Pheasant.’

1.45 a.m., Mersea Road

‘Blimey, it’s a real pea-souper,’ Kenton said above the roar of the engine, flicking the wipers on full. Although visibility was poor, he continued accelerating into the dark as they left behind the residential outskirts of Colchester and the orange glow of the street lamps.

‘A pea-souper is a fog. Or smog, to be more accurate, a smog caused by industrial waste, denoted by its colour. Clever lad like you should know that. This –’ Lowry rummaged in the glove compartment for some mints – they might give you sweet breath but, sadly, they did nothing to keep you awake – ‘this is just a mist. A cold one, I’ll grant you.’

The mist thickened as the road dipped through Donyland Woods.

‘Slow down, for Christ’s sake! You can’t see!’ Lowry cried, agitated. He was a bad passenger. Especially in Kenton’s cramped orange sports car.

‘Quitting smoking making you nervous, guv?’

The Triumph accelerated out of the dip.

‘No, it bloody well isn’t. Just slow down. There’s no hurry.’ It felt surreal, travelling in a convertible in these conditions. He was trying his best not to suggest that Kenton might consider fixing the roof.

Kenton eased off a fraction, ‘Not made any New Year’s resolutions myself.’

‘Wouldn’t bother.’ Lowry was giving up for health reasons, having developed a hacking cough. He didn’t give a fig that it was New Year, although the winter weather made it worse. No, it had been just a night like any other, albeit a busy one.

‘Always room from improvement, guv, quality of life—’

‘Don’t start banging on about quality of life at this time of the morning. Get out of the police force if you want quality of life . . . and don’t call me guv. How many times do I have to tell you? I’m not Dixon of Dock Green. Though I’m starting to feel as old as him.’ Lowry looked across at his driver. ‘Actually,’ he continued hesitantly, ‘I have been thinking about trying something new . . .’

‘Yes, giving up the fags.’

‘More than that . . .’

‘Not complaining about my car?’ Kenton prompted, the damp air catching his hair as turned to his passenger.

‘Me not complaining about this heap will improve your quality of life, not mine. No. I’ve decided I need to take up a hobby.’

‘A hobby? What, as in stamp collecting? Making model aeroplanes? That sort of thing?’

Lowry couldn’t make out his colleague’s expression in the dark, though he realized he needn’t fear being ridiculed. Daniel Kenton, for all his joking, was as sound as a pound – if anything, he’d understand.

‘Not quite so sedentary, no, although now I’m getting on a bit, it’s time to pull out of the gaffer’s boxing team. No, something outdoors.’

‘Cycling?’

‘No. Birdwatching.’

‘Ornithology? Crumbs. Sounds a bit . . . well . . .’

‘A bit what?

‘Well . . . Poofy? Was it the wife’s idea, guv?’

‘“Poofy”?’ Lowry said, surprised that someone so educated would use the term. ‘No – I haven’t even told her. It’s just an idea. I caught a programme on the telly and liked the thought of the fresh air, really. No more to it than that – not sure that qualifies me for a change in sexual preference.’

‘Sorry, sir. No offence. I was just wondering what the chief will have to say about it,’ said Kenton. ‘Ditching the boxing is one thing – I mean, you’re getting on and all, but . . .’

‘It’s none of his business.’ A vision of Stephen Sparks, the station’s pugilist chief superintendent, loomed across Lowry’s consciousness.

Kenton knew not to push him further. He was a good lad, Lowry thought, as he watched the tree limbs pass by, stark and white in the lights of the car, occasionally clawing ominously through the fog. Sparks, on the other hand, was not so agreeable. Lowry hadn’t really considered the effect this change in direction might have on the chief; as far as Sparks was concerned, the social side of the force was as crucial as the policing itself, if not more so. And Kenton’s observation was accurate enough: Sparks would more than likely view this harmless, gentle pursuit as on a par with being caught soliciting in public conveniences. But, in truth, he no longer cared; all his life he’d done things for other people. The boxing had started with his father. Even when the old man left them, Lowry had carried on, his need to impress him seamlessly replaced by the fuel of anger. And then the police force – and the shine had gone off that now. When did it happen? If it weren’t for his wife and Matt, he’d have thrown in the job years ago . . .

The Triumph drew to a stop. Kenton killed the engine, and silence descended on them.

‘Though, if it’s fresh air I’m after, there’s bags of it to be had travelling around in this thing with you,’ Lowry said, dispelling thoughts of sports and pastimes as he pulled himself out of the car on to the ice-cold causeway. ‘Watch your step,’ he said to no one in particular, flicking seaweed off his newish shoes. He spun his torch from left to right. On either side of the road there were narrow walkways bordered by two-bar wooden fences that ran the length of causeway. The motorist had hit the body as he came off the island. Lowry shone the torch to the right. Was it conceivable that the body had been brought in by the tide? He stepped up to the fence and looked into the murk of the salt marsh beyond the causeway. He couldn’t see the marshes, but he knew they were there.

‘Could the body have slipped between the gaps of this fence?’ he asked, more of himself than anyone else. He gauged the space between the bars – just short of a foot. Yes, probably.

‘The tide was a high one, guv,’ said a uniformed officer who had suddenly appeared beside Lowry. ‘Fully over the first rail.’

‘Sorry, and you are Constable . . . ?’

‘Jennings, guv, West Mersea.’ That would be why his face was unfamiliar, Lowry thought. He couldn’t keep up with the treadmill of Uniform – they tended not to stick at it so much these days; impatient for promotion. He stepped back from the rail and moved towards the huddle of silhouettes standing underneath an arc lamp in the middle of the road.

The body was male and clothed. It lay sodden and limp on the road. It reminded Lowry of a drunk he’d once found in the pouring rain in the middle of a lane near Tiptree.

‘Do you have a cigarette on you, son, by any chance?’ Lowry asked. The officer shook his head. Lowry shrugged. ‘Where’s the Dodger?’

‘The sergeant clocks off at nine, sir.’ The respect accorded to the station sergeant, a robust sixty-year-old who had manned the Mersea Station for more than thirty years, pleased Lowry. He crouched down and regarded the blanched corpse; his experience hinted it had been in the water for at least twenty-four hours. They needed to get the body to the lab; Lowry gave the signal and stood.

A torch bobbed towards him in the blackness.

‘There’s nothing more we can do tonight.’ Kenton approached, looking ashen under the spotlight. ‘West Mersea police have already scoured the road. No sign of the head.’

‘Sod the head for now.’ Lowry turned round in the darkness. ‘How did this get here?’ he said, tapping the corpse with a now-damp loafer. ‘Did it float in on the tide?’

-3-

1.50 a.m., Saturday, Colchester Garrison HQ, Flagstaff House, Napier Road

CS Stephen Sparks was cursing inwardly. They should have left the dinner party half an hour ago with the last guests, when Antonia had signalled she was ready, and not have had another brandy, as he’d insisted. Blast! The night had been fun, until now. Brigadier Lane stood in the hallway of his spacious quarters, speaking quietly into the telephone and occasionally shooting a glance in Sparks’s direction.

To a casual observer, the brigadier and Sparks might appear to be friends. Over the years, a genial relationship had developed between the two middle-aged men, fostered by social occasions like this evening’s lengthy dinner party. But the surface bonhomie masked a fierce rivalry. They held similar positions within Britain’s oldest-recorded town – Sparks was chief superintendent and Lane was garrison commander – and, while they didn’t compete in their professional lives, each had a deep-rooted need to outshine the other. It was channelled furiously through sports, particularly boxing. Both men had shared a passion for boxing since boyhood and were keen to instil the love of the sport into their respective commands; so, for the past ten years, local policeman and serviceman had met in the ring to batter the hell out of each other. Competition reached such a pitch that, in the Jubilee Year of 1977, the Colchester Services Cup was born, a prize which now glinted tauntingly from the brigadier’s trophy cabinet.

Sparks eyed the surrendered cup they’d lost the previous year before swigging the last of his brandy and replacing the glass heavily on the table. This telephone call could only be bad news. Sparks knew that Brigadier Lane tempered his deep, booming voice only for matters of a serious or upsetting nature. The policeman’s young fiancée shot him a pleading look: must we stay longer? He ignored her and watched as the brigadier replaced the receiver, his head bowed.

‘That was the hospital,’ Lane announced as he re-entered the room. ‘Young Daley . . .’ He rubbed his impressive beard, reluctant to say more in front of his wife and Antonia. But Sparks could read his expression and acknowledged what must have happened in silence. Shit, he’d never expected the lad to die. He’d only jumped off a wall, for Christ’s sake. He shook his head woefully.

‘The other boy has regained consciousness, according to a Dr Bryant,’ the brigadier continued. ‘We’ll have him transferred to the garrison hospital straight away.’

Abbey Fields, the military hospital. That’s the last thing we need, thought Sparks. Once the army had him, the police would never get access.

‘Really? Surely it’s best not to move him. Why not leave him in the General?’

‘Army takes care of its own, Stephen, you know that.’

Yes, only too well. It was because the soldier had been in a critical state that the civilian police had successfully overruled the military police – Lane’s Red Caps – in the first place. The brigadier’s wife got up off the sofa and moved to comfort her husband. As if he cares, thought Sparks – the embarrassment is all that brute will be worried about. And the fact he’s lost a good bantamweight fighter. Daley had a lethal upper cut.

Sparks rose, along with his fiancée.

‘I’m very sorry, John.’

‘Not your fault,’ the brigadier replied. Though, of course, Lane would hold him responsible for allowing yobs to run riot in the high street on New Year’s Eve. ‘Have you caught the little sods yet?’ he demanded.

‘We’re making inquiries. This, of course, ups the ante . . .’

‘Murder?’ piped up Lane’s wife, wide-eyed.

‘Let’s not be too hasty,’ Sparks urged. ‘There’ll be a full investigation.’

‘Damn right there will,’ Lane put in.

Sparks held out Antonia’s coat for her to put on. Yes, he thought, but don’t you go poking your oar in with the local Gestapo. The last thing he wanted was MPs crawling all over this.

‘Right, we must be off. Thank you for a lovely evening.’ Handshakes and kisses were exchanged. ‘I’ll check in at the station on the way home and call you first thing in morning, John.’

Sparks ushered Antonia to the door, his hand a little too firm in the small of her back. ‘Lovely evening, thank you,’ he repeated forcefully as the bitter night air filled the hall. Lane nodded in silence on the threshold, and his wife smiled wanly, aware that the unwelcome news had ruined a pleasant evening.

*

‘Did you have to practically push me out of the front door?’ Antonia shivered as Sparks fumbled with the cap for the de-icer in the VIP parking bay. ‘What was all that about, anyway? What did she mean, “murder”?’ She wrapped herself tightly in her long fur coat.

‘Typical New Year’s Eve trouble – a ruckus between the locals and a bunch of squaddies,’ explained Sparks.

‘And someone was killed? There’s always fighting in town over Christmas, but good heavens, what’s the place coming to?’ she said, appalled.

Sparks bristled. ‘Yes, but this time a dozen or so yobs chased two lads and cornered them at the castle. They jumped from the north wall, not knowing it was a twenty-foot drop. Both are in hospital, and one just died.’

They sat in the Rover in silence. Sparks turned on the blower to de-mist the windscreen. Antonia brushed her lush blond hair from her face.

‘Do we really have to go to the station tonight?’

Sparks ignored her and picked up the radio handset. ‘Get me Lowry,’ he said.

2.45 a.m., Colchester CID, Queen Street

‘Ah, there you are. Just seen Kenton slope off. Where’ve you been?’ Sparks said loudly. As usual, the chief seemed oblivious to the late hour, marching around bright-eyed and energetic in his attic office, as though it were a fresh spring morning. This ability of his to be wide awake at all times grated on Lowry. ‘The night sergeant has filled me in on the obstruction on the Strood.’

‘Kenton’ll be back out there, on the mud at dawn, don’t worry. And I’ve just been phoning to check on my son. He’s sleeping over at my wife’s parents.’

Sparks reached for a bottle from the small, tatty cabinet. The chief wasn’t interested in Lowry’s domestic arrangements, nor, it seemed, in the body on the Strood.

‘We have a problem,’ Sparks continued. ‘Drink?’

Lowry nodded and took the generous measure of the chief’s favourite malt offered to him. Sparks was in civvies: a neatly tailored suit in Prince of Wales check, a white shirt and a navy tie at half-mast. When out of uniform, the older man, with his cropped hair and bulky frame, didn’t look like a copper, especially in a get-up that wouldn’t look out of place on an East End gangster.

‘Cheers.’ He raised the glass. ‘What’s happened?’

‘The soldier boy who fell off the wall in Castle Park is dead.’

‘Oh.’ Lowry didn’t need an explanation. In this town, a soldier’s death was a cause for concern.

Colchester was one of the country’s largest garrison towns. This had been the case since the Roman invasion in ad 43, and every policeman in Queen Street knew the history, to varying degrees. In military conflicts across the ag

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...