- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

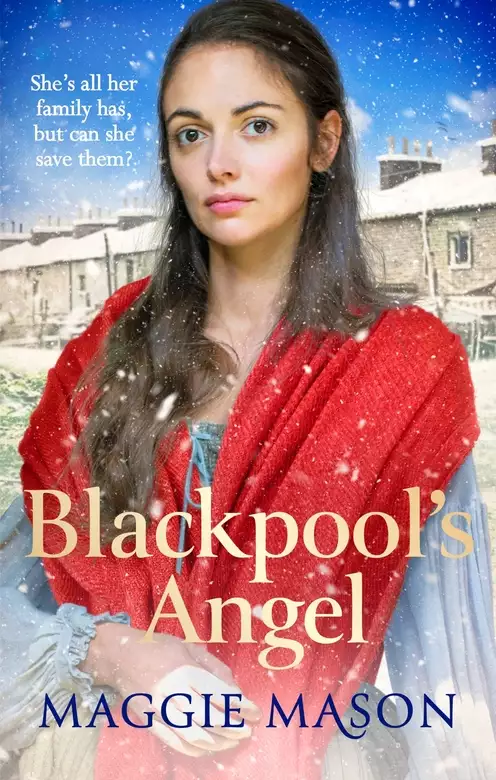

Synopsis

Blackpool, 1893

Tilly has come a long way from the run-down tenements in which she grew up. She has a small but comfortable home, a loving, handsome husband, two beautiful little'uns — Babs and Beth — and she earns herself a little money weaving wicker baskets. Life is good.

Until the day Tilly returns home to find a policeman standing on her doorstep. Her Arthur won't be coming home tonight — nor any night — having fallen to his death whilst working on Blackpool tower. Suddenly Tilly is her daughters' sole protector, and she's never felt more alone.

With the threat of destitution nipping at their heels, Tilly struggles to make ends meet and keep a roof over her girls' heads. In a town run by men Tilly has to ask herself what she's willing to do to keep her family together and safe — and will it be enough?

The perfect listen for fans of Mary Wood, Kitty Neale, Val Wood and Nadine Dorries

Release date: April 7, 2020

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blackpool's Angel

Maggie Mason

Next week, the first week in September, four-year-old Barbara and Elizabeth, or Babs and Beth, as she and Arthur called them, were to start their lessons at the Church of England free school. Tilly was filled with great pride at this – her own young ’uns, learning to read and write! She couldn’t believe it. Eeh, that’s sommat I’ve allus wanted to do. But there wasn’t a chance with me Aunt Mildred thinking that learning such skills weren’t for the likes of poor folk like us.

The pain of her Aunt Mildred’s passing a year ago ground into Tilly. For all her old-fashioned thinking, her aunt had been a kindly soul and had taken Tilly in when her parents died from typhus in 1868. Tilly had been just a few months old.

‘Learn a trade that’ll stand you in good stead, lass. It’s the only way,’ Aunt Mildred had said. And to that end she’d passed on her weaving skills and now Tilly could make anything out of hedgerow pickings and grass – from baskets to hats, cots to plant-pot holders and mats. And all intricately designed using different-coloured materials. But willow was what she most loved working with. Not easy to come by, but sometimes traders had some to sell when they came up to Blackpool from the southern counties, especially Somerset. The finest willow came from there.

Tilly sighed as she thought of how Arthur would never let her put these skills to helping to earn money for the family. Not that they needed it now, but there had been some lean times. He had his sayings did Arthur, aye, and he stuck by them. ‘I’m the breadwinner, lass, not you,’ he’d say if she broached the subject of selling some of her baskets. ‘You’re me wife, you keep me house clean, cook me meals, bring up our young ’uns and aye, see to me needs in our bed.’

This last thought gave Tilly a pleasurable twinge. Arthur said she was made for loving, and she always enjoyed it when he took her to him.

Tossing her thick raven-coloured hair away from her face to cool the heat that had risen within her, Tilly knew she had all that men desired in her voluptuous curves. Of medium height, her breasts were larger than most women’s. Her tiny waist accentuated this.

‘By, lass, God gave it all to you,’ her Aunt Mildred would say. ‘What with your beauty, and them flashing dark eyes, you’ll have trouble knocking at your door. Don’t you be bringing it to my door, though, and that’s a warning.’

Tilly smiled. Aunt Mildred had a way of scolding you that made you giggle rather than feel chastised.

‘Ma, Ma, look.’ Babs and Beth’s heads were just visible above the tall grass of the field. As she walked towards them, she looked over to where they were pointing and knew the same wonderment that lit their faces at the sight of the tower. A feeling of pride in her Arthur for being one of the workers fitting together the huge iron structure assailed her. Almost finished, the Blackpool Eiffel Tower, as it was known on account of it being modelled on the Eiffel Tower in Paris, now stood at over three hundred feet high.

It was the mayor, John Bickerstaffe, who started it all, or so they say, but all that didn’t matter. It was her Arthur getting a job on the building of it that mattered. For that had changed their fortunes. They’d moved from the boarding house in Albert Street that housed a dozen or so families, to their own two up, two down terraced house in Enfield Road, North Shore.

Every thought of Arthur warmed her. Their love for one another knew no bounds. Arthur had been brought up in Enfield Road, just a couple of streets from her. She’d known him all her life, and they’d played together as young ’uns, knowing then that one day they would marry.

Tilly laughed as she looked down at the twins playing with a worm they’d dug up; she never ceased to be amazed at their enjoyment in everyday things.

‘Gather yourselves, me lasses, we’re to head for home. Your da’ll be in by the time we get back, and I’ve that lovely stew on the hob waiting for us all.’

Tying the vines into a bundle, Tilly slung them over her shoulder and began the mile walk over the fields to her home. In the distance she could see the sea sparkly in the August sun. Blue and calm today, it could whip up to a churning, angry crashing of waves as quickly as a nod of the head if it had a mind to.

Blackpool had changed a lot over the last few years. Visitors from all over came to ‘take the waters’, as the posters put it, which meant folk dipping themselves in the mostly freezing Irish Sea, believing it could heal all manner of ailments. Whether it could or not, Tilly didn’t know – but she hadn’t much faith in it doing so as those who lived in Blackpool ailed just as much as the rest of the country.

But for all that, she knew that the idea brought folk flocking and folk brought money and Blackpool was prospering. Guest houses and hotels were springing up all the time, which bode well for Arthur’s continued employment once the tower was completed.

Life was good, and Tilly was grateful; even her sadness at not being able to have any more children didn’t mar her feeling of everything being all right with her world. She had her twins and her being damaged inside by their birth wasn’t the end of the world. Nothing about her had been impaired otherwise, and she and her Arthur could make love till the cows came home without worry of increasing their family to the extent that they would suffer poverty, as happened with a lot of folk. Look at her best friend, Liz. Five young ’uns under eight and she had her belly up again. The lass was worn out and she never knew where their next meal was coming from.

Tilly and Liz had been friends since childhood. Liz still lived in her mam’s house a couple of streets away from Enfield Road. Badly in need of repair, it was a damp, cold place at the best of times.

Thinking of Liz, Tilly determined to call in on her way home and made a detour as she came into Blackpool.

When Liz opened the door to greet her a sea of faces surrounded her, all eager to see who was visiting. Shooing her brood away, and hitching the youngest higher on her hip, Liz, as always, showed how glad she was that Tilly had called round. ‘Eeh, lass, it’s good to see you. I have the pot on, and some tea that I got this morning – I’ll make us a cuppa. Mind, I’ve naw milk, but it’ll be hot and sweet as I’ve got a bag of sugar an’ all.’

‘That’ll be welcome, Liz, though I ain’t got long.’

‘Put your bundle down. Eeh, look at the young ’uns, they look worn out. Have you been trundling them over the fields again, Tilly?’

‘Aye, we’ve had a grand day.’

Liz looked tired. The vibrant girl she’d once been had gone. Her fair, always unruly, curly hair looked wiry and lacklustre. Her skin that used to glow was now pale and seemed as though it was pulled tight over her cheekbones. Her once sparkling blue eyes now looked grey and weary and were sunk into dark sockets.

Tilly looked around her as she stepped inside. Despite her poverty, Liz kept her little house clean and tidy. Threadbare rugs were brushed to within an inch of their life, and the floors beneath scrubbed till the flagstones had a sheen on them. Remnants of Liz’s mam’s furniture – a scrubbed wooden table, and two big armchairs each side of the fire – looked fresh with a crisp white cloth covering the centre of the table and antimacassars of white cotton draping the arms and backs of the brown chairs. ‘Sit yourself down, lass. I won’t be a mo.’

Glad to take the weight off her feet, Tilly sank into the chair. Beth and Babs had found renewed energy with the prospect of playing with Liz’s lot and were soon out in the backyard with them, leaving the little living room a peaceful haven.

‘So, what are you thinking of making this time, lass? By, your house is full of beautiful baskets and the like, I’ve a wonder you can fit any more in.’

Telling Liz of her plans, Tilly was soon full of the twins starting school. ‘I can’t believe it, we didn’t get the chance, did we, Liz? I were working in Dottie’s sweet shop by the time I were ten, and that were me lot. I learnt how to count, though, and was good with the money transactions, even though I couldn’t read and write. And you fared no better – with your ma taking in washing from the guest houses, you were allus turning that mangle.’

‘I have the muscles to prove it an’ all, but I ain’t ever been interested in learning. And I ain’t bothered if me kids do or not. It’ll only be more expense for me. More often than not I keep our Alfie at home. He’s more use scouting around for what he can make from the tourists. Polishing their shoes, or carrying their bags with their bathing stuff in. He comes home with a good few pennies most days.’

Tilly didn’t say anything to this, but she felt the pity of it as, to her mind, an education was a way of opening up the world to the young ’uns and helping them to make more of themselves, though she knew the Alfies of this world would flourish in Blackpool, educated or not.

This thought hadn’t died when he came in the door. ‘Hello, Aunty Tilly. I’ve sommat as you’ll like. I’ve been helping in a rock factory today. I walked into that shop on the prom asking for work and they took me in the back and set me on. I helped to roll the rock an’ all, and they let me have some bags of the chippings when they cut it. I can sell you a bag of bits for Babs and Beth for a penny.’

Liz gently cuffed the cheeky eight-year-old Alfie around the ear. ‘Oy, what’re you up to? You didn’t steal them bits, did you?’

‘Naw, Ma, I were given them, and I did such a good job, helping to keep the floors clean and fetching and carrying the bags of sugar, besides having a turn at the rolling, that I got meself a regular job. Two days a week. Me earnings will be sixpence and pickings of the bits that break off during the cutting.’

‘Eeh, lad. Eeh, me little Alfie, come here, and let me give you a hug.’

‘Gerroff, Ma. Don’t come all sloppy over me.’

‘I’ll buy a bag off you, Alfie, it’ll be a treat for me girls.’

‘Ta, Aunt Tilly. Here you go. I’ve five bags altogether. I’ll let me sisters and brothers share one, but the other four I’m going to sell down the prom tomorrow as that’s going to be the sideline of me job. I should make a pretty penny or two that way.’

‘By, lad,’ Liz looked with pride at her eldest son, ‘you never cease to amaze me. Now, don’t let your da knaw, or he’ll be after you to give him some money for his drink.’

‘I’ll keep it secret from him, Ma, and you’ve to make sure the young ’uns do an’ all. I’ll start a stash in that tin I have under me bed, but you can help yourself from it whenever you need to. And I’ll cough up me sixpence to you an’ all.’

‘You’re a good lad, Alfie. You’re worth twice what your da is, the lazy sod. He’s away to his bed at this minute. He came in tipsy again. Lost his job and spent his pay-out on the way home. I’m at me wits’ end with him.’

As Alfie went out the back door, Tilly had the feeling that he didn’t want to hear about his da as Liz hadn’t finished talking before he’d disappeared. ‘How do you cope, Liz, love?’

‘I don’t. I live in fear of being evicted as I’m behind with me rent. And feeding me brood is difficult. Alfie’s little offerings help and Larry’s coming up to seven now, so he can bring a ha’penny in now and again running errands for them in the street, and he’s good with numbers an’ all. I don’t knaw how, or where he gets that talent from, but he helps at Dottie’s sweet shop now. He fills little bags with an ounce of toffees so they’re ready for selling rather than old Dottie having to do the job as the customers come in. But she’s a mean old cuss and only gives him a farthing now and again.’

‘She was allus like that when I worked for her. Look, Liz, I can help you out, lass. I have enough in me purse for your rent – for this week, anyroad.’ Tilly dug her purse out from the pocket of her frock and handed some coins to Liz.

‘Naw, lass, I – I mean, are you sure?’

‘Aye, I am, and I’ve a big pot of stew on at home. If you give me a pan and send Alfie and Larry with me, I’ll fill it for you. They’ll manage a handle each to get it back here. If not, I’ll put it on the pram and they can wheel it round, how’s that, eh?’

‘Eeh, Tilly, that’d be a godsend. I’ve some bread baked off an’ all. I can easily fill their bellies with stew and bread.’

‘Aye, and if you mix up some dumplings, you can boil the stew up to cook them in.’

‘I’ll do that. I’ve got some lard, and plenty of flour. They’re things I allus keep in as I can do a multitude of things with them to feed the young ’uns.’

‘Don’t ever go short, Liz, I’m allus telling you, as I’d give you owt that you need.’

‘I knaw, you’re a good friend.’

‘I mean it. Send one of the young ’uns round to mine if you need owt, and if I’ve got it, you can have it. Now, I’m to get meself away. I’ll have Arthur in afore I knaw it. I’ll see you later, lass. Take care.’

Tilly wanted to add that Liz should try to dodge some of the blows that came her way, as she hadn’t missed the bruises on Liz’s arm. A sigh escaped her. How was it that Eddie had turned out like he had? Though she had to admit, he was always aggressive as a young ’un. She remembered how the four of them, Arthur, Eddie, Liz and herself, would play snobs, a game they played with stones. They’d start with five, four on the ground and one in their hand. They’d toss the one in their hand and try to pick up others before they had to catch the one they had thrown in the air, all having a good time, giggling and teasing, but Eddie would spoil it. Especially if he was losing. He’d kick the stones away, saying it was a daft game. Once Eddie had beaten Arthur up when he’d challenged him to stop being babyish. That had been a changing point in their friendship and had taken a long time to mend. Eddie’s family had moved away the next year, somewhere down the Midlands, and Tilly had thought that was that, but he came back looking for Liz a few years later and, against Tilly’s advice, Liz fell for him and they married. Eddie was idle. He never kept a job for long, even though there was an abundance of jobs in Blackpool for young men. And what with his temper, his drinking, and aye, his womanising, he led poor Liz a merry dance that she didn’t deserve.

As Tilly turned the corner, she was surprised to see a man talking to Mrs Haggerty and Mrs Brown, her neighbours. The three were standing outside Tilly’s door. Something about them made her blood run cold.

‘Are you all right, Aunt Tilly? You’ve gone very white.’

Tilly couldn’t answer Alfie. She held Babs and Beth’s hands tighter as if clinging on to them would ward off the dread in her.

Mrs Brown saw her at that moment. Her head shook from side to side. ‘Eeh, me lass, me poor lass.’

Tilly couldn’t speak. She stared at the two women. How she’d walked the last ten or so yards towards them she didn’t know.

‘Mrs Ramsbottom?’

Tilly nodded at the man. He looked official, with his bowler hat and long black coat. ‘I’m afraid I—’

‘Let her get inside, man.’ Mrs Haggerty came forward as she said this and took Tilly’s arm. ‘You, Alfie, mind the young ’uns for a mo, there’s a good lad. Keep them playing, we have sommat to tell your Aunt Tilly. And you, Larry, run and fetch your ma. Tell her Mrs Haggerty told her to come as your Aunt Tilly will need her.’

‘What? Why … ?’ Tilly could hardly voice the words. She had a feeling inside her that her world was coming to an end.

‘Come on, lass. Let’s get you inside.’

Propelled forward, Tilly went into her house. For some reason she couldn’t fathom, nothing about it seemed familiar to her anymore. The usually welcoming living room that led off the street, with its cosy chairs and sofa in beige and brown, and cream rug, covering the polished brown linoleum, looked as though they didn’t belong. And she wanted to take her hand and push her shining brass ornaments off the mantle shelf and have them clatter to the floor. Why she should feel like this she didn’t know.

‘What’s happened? Is … is it Arthur? Naw, don’t let it be. Naaaaw.’

‘Sit down, lass. There’s been an accident. The gentleman will tell you.’

With this from Mrs Brown, Tilly felt herself being gently steered towards one of the chairs, but she didn’t want to sit in that one. That one was Arthur’s and he’d be in soon to sit in it himself.

‘I’m very sorry to tell you this, missus, but, well, the scaffolding gave way and … well, Mr Ramsbottom fell …’

Whatever else he said was drowned out by her moaning scream. A sound that assaulted her own ears and revealed the truth to her that there was such a thing as a broken heart. She felt hers split in two when he uttered the words, ‘killed instantly.’

The last three days had passed in a haze of weeping and dealing with folk coming in and out of the house. During that time the inquest had also been opened and adjourned, and she had been granted the right to bury her Arthur.

His body now lay in an open coffin on the table at the back of the living room. The sun streamed through the windows and lit his beautiful face. It didn’t matter to Tilly that that face was broken; she knew in her mind the contours of how it always had been – the clear-cut cheekbones and the square chin. The overly big nose, that didn’t detract from how handsome Arthur had been … Had been. No, No, I want my Arthur back. I don’t want him dead.

Looking down at him, Tilly wanted to make him all better. To put the crooked, flattened nose back into place, and to heal the slash across his cheek. Touching him, she wasn’t repelled by how cold he was, but wanted to get in beside him and warm him up. Cuddle him to her and soothe the pain she knew he must have felt on impact as his bones crumbled and he took his last breath.

Fifty feet he fell. Fifty feet that would have taken seconds to pass and yet, what fear Arthur must have felt in that time. Stroking his waxen cheek, Tilly whispered her love for him. A cough behind her made her want to scream. She didn’t want the lid to be put on the coffin. That would be final. Her Arthur would be gone forever, encased in a wooden box, feet beneath the earth. Never again would she be able to see him, touch him …

A hand took her arm. ‘Come on, lass, let the men do their job. Say goodbye to Arthur.’

Liz’s voice didn’t sound like Liz’s voice. Her throat sounded sore. Her nose blocked. She too had cried buckets these last days. Holding Tilly, rocking her, trying to give and receive comfort. But there was no comfort, only a black pit that held a future that Tilly didn’t want to acknowledge. A cold future with no Arthur. One in which she would never again be held by him, kissed by him. The sound she’d made many times came from her once more. A long drawn-out moan that hurt her lungs and rasped her throat, but she let herself be moved away, let herself be held. Supported by the hateful Eddie, who’d at least shown some decency towards her these last days, she stepped outside.

There, the sun shone and though there was a stillness in the folk that lined the street, the rest of the world carried on unaware of her pain. Birds sang. Horses’ hooves resounded on the tarmac of Devonshire Road that ran along the bottom of their street. And then the horses of the dray that would take Arthur to his final resting place in Layton fidgeted. One snorted loudly. All a rude intrusion into her world of grief.

Looking up the street, she saw Babs and Beth wave to her. Mrs Lipton, their teacher-to-be, had offered to collect them and keep them for the day. Tilly waved back and, as she did, she had the feeling that they too would leave her. Panic gripped her. She wanted to run to them and hold them to her and never let them go, but Eddie’s arm tightening on her waist stopped her. Repulsion shivered through her. She pulled away from him. No one noticed as at that moment the undertakers stepped out of the house bearing Arthur’s coffin.

Everything passed in a daze after that and it seemed like no time had gone by before it was all over – the service, the burial, and the wake held in the church hall. Now Tilly found herself sitting alone, with the ticking of Aunt Mildred’s mantle-shelf clock filling the space around her. Her thoughts were of despair. The cost of the funeral had all but taken the money she’d had in the rainy-day pot that stood next to the clock, but when she’d squirrelled away the odd copper here and there, she hadn’t had any thoughts that there would be this kind of day to pay for.

Getting up and shaking the pot, the pennies rattled around inside. There’d hardly be enough to pay one week’s rent, let alone buy food, though she comforted herself on this last as she had a well-stocked cupboard. But how to get money after that? Even if she could get hold of some wicker and make some baskets, she couldn’t make enough to start up as a trader – she’d need at least ten wicker items to even think of going down to the beach to sell. Besides, the season would be over in a few weeks; already those who owned the houses on the promenade were beginning to close them up.

Jobs would be scarce then too, as most traders would close their stalls. And what of the twins? Who would look after them while she worked? Liz had her plate full and she didn’t know who else she could ask.

A knock on the door made her jump. She glanced at the clock – ten past ten, no one had ever visited her at this hour!

Opening the door, she had to step back as Eddie lolled towards her, his clothes and his breath stinking of beer and fags. His voice slurred. ‘I called on me way shome to shee if yoush all right, darling?’

With her heart pounding a fear around her, Tilly held on to the door trying to prevent him from coming inside, but his weight as he leant on it was too much for her. ‘I’m fine, Eddie, ta. Now, take yourself home, it’s late and Liz will be looking out for you.’

‘That cold fish. I desherve shomeone better. Shomeone warm like you. I could keep you happy like Arthur did. He told me you liked it, he shaid you and him did it every night. Liz only letsh me near her now and again. I go to Prossie Pam a lot. She knowsh how to get a man going. But I could come here, and then you wouldn’t mish Arthur sho much.’

Horrified, Tilly stepped further into the room as Eddie leered at her. ‘Please go. I don’t want you. I wouldn’t let you touch me, you filthy animal.’ With her temper rising, her fear left her, and she reached for the poker that was kept by the hearth. ‘Come near me and you’ll get a wallop with this. You’re disgusting, Eddie Philpot. Me Arthur’s not cold in his grave and you – his supposed friend – makes a pass at his missus. You should be ashamed of yourself. Get out! Go on. Get out!’

Eddie stared at her for a moment, his stance one of a sober man now. ‘Well, p’raps itsh too soon, but I knaw you’re going to yearn for it, and I’ll be ready, me darling. Just give me the nod.’

‘That’ll be never. You’re me friend’s man. And I don’t want you or any man. Now go, Eddie, just go.’

He went out of the door, leaving Tilly shivering from head to toe. Dropping the poker, she ran to the door and turned the key. The strength went from her body at the sound of the lock clunking into place. She leant her back against the door, but her legs gave way and she slumped to the floor. The same moan she’d hollered so many times these last days came from her as her body gave way to a deluge of tears she couldn’t stop. Eddie had just made her troubles threefold as she knew he wouldn’t give up. Oh, Arthur, Arthur. I knaw it would have been lads’ talk, but of all the folk to share our intimate details with, you shouldn’t have chosen Eddie. ‘Oh, God, help me, help me.’

It was a few days later before Tilly ventured out. She’d had callers, but Liz hadn’t been to see her, and this had worried her as to what Eddie might have said about the incident. Had he feared in the light of the next morning that she would tell Liz what had happened, and, not liking the fact that she’d rejected him, chosen to discredit her? Tilly could think of no other reason why Liz wouldn’t come around to see how she was and to offer her help. But today, she had to take the twins to their lessons in St Paul’s on Edgerton Road and had decided she would go and see Liz before going home.

As she arrived in Fairfield Road, her nerves almost got the better of her and she hesitated before turning down Liz’s street. Taking a deep breath, Tilly knew she had to do this. Having no communication with her friend was too much to bear on top of everything else that weighed her down.

Trepidation shivered through her as she opened Liz’s door and called out. As Liz stood up from the chair she’d been sitting in, her whole demeanour spoke of her anger.

‘Liz, I—Oh, Liz, it weren’t my doing, I took the poker to him, I did … I’d never, I mean … Oh, Liz, please believe me.’

‘Take your word over me husband’s, you mean, eh? And accept that me husband made a pass at you? Naw, Tilly. I’ve allus had a jealousy in me where you’re concerned. Me Eddie allus fancied you more than he did me when we were young ’uns, and now, the minute you’re a free woman, you entice him. I’m proud of how he resisted you and came home to me. He offered you help, Tilly. He called in to see as you were all right, and all you wanted was the comfort of him in your bed, and with you just having buried your poor Arthur. You should be ashamed of yourself.’

‘It weren’t like that, Liz. It weren’t.’

‘I think as you’d do best to leave. Me and you have been friends since we were born, and aye, you’ve been a good friend to me in me time of need, but to do this to me, when you knaw as me Eddie is one to stray and how much that hurts me? Well, I can’t forgive you, Tilly, and I never will.’

‘It’s Eddie you should never forgive. I’ve done nowt. He called on me with the intention of lying with me. How he could think I’d even fancy him, or anyone for that matter, when me heart’s broken from me losing me lovely Arthur, I don’t knaw. Eddie’s a wrong ’un and allus has been. He don’t deserve you, Liz. But … but I – I don’t knaw how I’m going to manage without you. Help me, Liz. If you never do owt for me again, help me at this time in me life.’

For a moment Liz looked unbending. Her arms were folded across her chest. Her body was stiff, making her protruding belly look bigger than usual. But a tear seeped from the corner of her eye, and Tilly realised that to accept the true version of events – that her Eddie had tried to seduce her best friend – would cause such pain to Liz that it wasn’t that she didn’t believe, she just couldn’t allow herself to.

Walking out of the door, Tilly hoped against hope that Liz would call out to her, but she didn’t.

To have her heart broken twice in such a short time was unbearable to Tilly. But she lifted her head high in case Liz was watching through the window and walked on unsteady legs towards her home.

Loneliness engulfed her once she closed the door on the world. Making it to Arthur’s chair, she snuggled into it, trying to feel his presence and gain comfort, remembering how often he’d sit here and say, ‘Come and sit on me lap, lass, and let’s have a cuddle.’ And how he would start to tickle her until she was crying with. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...