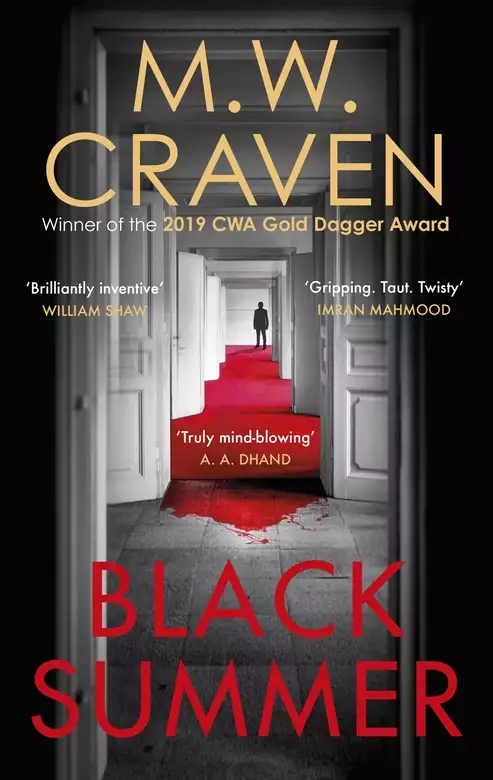

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

After The Puppet Show, a new storm is coming . . .

Jared Keaton, chef to the stars. Charming. Charismatic. Psychopath . . . He's currently serving a life sentence for the brutal murder of his daughter, Elizabeth. Her body was never found and Keaton was convicted largely on the testimony of Detective Sergeant Washington Poe.

So when a young woman staggers into a remote police station with irrefutable evidence that she is Elizabeth Keaton, Poe finds himself on the wrong end of an investigation, one that could cost him much more than his career.

Helped by the only person he trusts, the brilliant but socially awkward Tilly Bradshaw, Poe races to answer the only question that matters: how can someone be both dead and alive at the same time?

And then Elizabeth goes missing again - and all paths of investigation lead back to Poe.

Release date: June 20, 2019

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 399

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Black Summer

M.W. Craven

It is six inches long and weighs less than an ounce. Its head is grey, its throat is pale yellow and its plumage a delightful orange. It has a stubby pink beak and its eyes shine like glass peppercorns. Its staccato chirping brings a smile to all who hear it.

It is a thing of remarkable beauty.

Most people, when they see an ortolan bunting, want to keep it as a pet.

Not everyone.

Some people don’t see its beauty.

Some people see something else.

Because the other remarkable thing about the ortolan bunting is that it’s the main ingredient in the most sadistic dish in the world. A dish that demands the tiny songbird is not only killed, it is tortured …

The chef had bought two, a month earlier. You can’t shoot ortolans without destroying them, so she’d paid a man to net them. He’d charged her one hundred euros each. A steep price but the fines if he’d been caught were far steeper.

She’d taken them home and fattened them up the way the cooks at Roman banquets had done: by stabbing out their eyes. For the two ortolans, day turned into night.

And at night they fed.

For a month they gorged on millet, grapes and figs. They quadrupled in size. Fat enough to eat.

A dish fit for a king.

Or an old friend.

When the call came she’d taken them over the Channel herself.

She’d disembarked at Dover and driven all night to a restaurant in Cumbria called Bullace & Sloe.

Her two diners could not have been more of a contrast.

One man wore a fine suit with a high collar. It looked oriental in design. His shirt was stiff and white and his cufflinks were pure gold. He appeared cultured and at ease. He had an affable smile and would have raised the tone of any dining room in the world.

The other man wore mud-spattered jeans and a wet jacket. His boots dripped dirty water onto the dining room floor. He looked as though he’d been dragged through a gorse bush backwards. Even in the low light of the flickering candles he looked nervous and fidgety. Desperate.

A waiter approached their table and presented the birds in the copper pots they’d been roasted in.

‘I think you’ll enjoy this dish,’ the man in the suit said. ‘It’s a songbird called the ortolan bunting. Chef Jégado brought them over from Paris herself, and not fifteen minutes ago she drowned them in brandy …’

His companion stared at the bird: it was toe-sized and spitting in its own fat. He looked up. ‘What do you mean, “drowned”?’

‘It’s how you get brandy into their lungs.’

‘That’s barbaric.’

The man in the suit smiled. He’d heard this all before when he’d worked in France. ‘We throw live lobsters into boiling water. We rip the claws off living crabs. We force-feed geese for foie gras. There is suffering in every bite of an animal we take, no?’

‘It’s not legal then,’ the man in jeans countered.

‘We all have legal problems. Yours are more serious than mine, I think? Eat the bird, don’t eat the bird, it is all the same to me. But, if you decide to, do as I do. It will create a scent-tent and hide your gluttony from God.’

The man in the suit placed a starched, blood-red napkin over his head and put the bird in his mouth. Only its head remained outside. He bit down and the head fell onto his plate.

The ortolan was scalding hot. For a minute the man in the suit did nothing but rest it on his tongue and take small, rapid breaths to cool it. The delicious fat began to melt down his throat.

He sighed in appreciation. It had been six years since he’d been able to dine like this. He chewed into the bird. An explosion of fat, guts, bones and blood filled his mouth. The sweet flesh and bitter entrails were sublime. The grease that coated the roof of his mouth was breathtaking. Sharp bones pierced his gums and his own blood seasoned the meat.

It was almost overwhelming.

And finally his teeth penetrated the ortolan’s lungs. His mouth was flooded with the delicious Armagnac.

The man in the jeans didn’t touch his bird. He couldn’t see the man in the suit’s face – it was still under the napkin – but he heard the crunch of bones and his sighs of pleasure.

It took fifteen minutes for the man in the suit to finish eating the songbird. When he emerged from underneath his napkin, he wiped away the blood that was dribbling down his chin and smiled at his guest.

The man in the wet jeans spoke, and the man in the suit listened. After a while, and for the first time that evening, the man in the suit showed a hint of annoyance. Fear flashed across his perfectly composed face.

‘It’s an interesting story,’ the man in the suit said. ‘But alas, one we can’t continue, I’m afraid. It seems there are others joining us.’

The man in the wet jeans turned around. There was a figure dressed in an ordinary, workaday suit standing at the door. A uniformed police officer was by his side.

‘So close.’ The man in the suit shook his head and beckoned the police officers inside.

The plainclothes officer approached the table. ‘Sir, could you come with us, please?’

The man in jeans, his eyes darting, searched for a way out. The waiter and the chef were both in the kitchen so they would block his escape.

The uniformed officer extended his baton.

‘Don’t do anything stupid, sir,’ the plainclothes officer said.

‘Too late for that,’ the man in jeans snarled. He grabbed a half-full wine bottle by the neck and held it in front of him like a club. Its contents sluiced down his still-damp shirt.

It was a Mexican stand-off.

The man in the suit watched it unfold, the smile never leaving his face.

‘You have to let me explain!’ the man in jeans hissed.

‘You’ll get your chance tomorrow,’ said the plainclothes officer.

The uniformed policeman moved to the man’s left.

The kitchen door opened. The waiter walked out. He was holding a platter of oysters. He saw what was happening and dropped the metal dish in surprise. Ice cubes and shellfish scattered across the flagged floor.

It was the distraction they needed. The uniformed officer went low; the plainclothes officer went high. The baton took the man behind the knees and the plainclothes officer’s punch caught him on the jaw.

The man in jeans collapsed. The uniformed officer knelt on his back, pushed his head into the flagstone floor and handcuffed him.

‘Washington Poe,’ the plainclothes officer said, ‘I’m arresting you on suspicion of murder. You do not have to say anything, but it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something that you later rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence.’

The blue light has gone out in rural England. Grand old Victorian police stations have been consigned to history, reduced in number and replaced by modern, well-equipped and soulless centres of excellence.

And gone too is the local bobby. They now only exist in the minds of those who yearn for a rural idyll. These days, police officers mostly see their patch through the windows of a patrol car.

Tesco has twice as many twenty-four-hour shops as the police have twenty-four-hour stations.

Nowhere has been hit harder than Cumbria. A county of almost three thousand square miles – geographically, the third-largest in England – has just five full-time police stations.

Alston, in the North Pennines, the highest market town in the country, never stood a chance. Its police station, a large and beautiful detached building, was sold in 2012 and replaced with a police desk. On the fourth Wednesday of the month, a member of the Eden Rural neighbourhood policing team – designated as ‘problem solvers’ – would drive all the way up there, sit behind a desk in the library and listen to people complain.

Problem Solver Constable Graham Alsop hated the fourth Wednesday of the month. He also hated being called a problem solver. Some of the gripes he was forced to listen to were so mind-numbingly petty, so headbangingly intractable, he felt the town sometimes had the collective intelligence of fish bait.

He didn’t need to go back further than a month to find a good example of what he had to put up with. An elderly gent had approached him and dumped a full bag of dog turds on his desk. Fucking dog turds. The man had said he was sick of finding them in with his prize-winning Lady Penzance roses. Claimed his neighbour was letting her gimpy dachshund defecate all over them as revenge for beating her in the village show. He’d demanded that Alsop take them to the ‘lab’ for DNA testing. He’d seemed surprised to find out there was no ‘lab’, nor was there a dog DNA database that could compare one turd against another. It was a civil matter and the constable accordingly advised him to see a solicitor. And he was to take his bag of shit with him. Of course, if it escalated into an infamous dog-turd murder, Problem Solver Constable Alsop would have some explaining to do, but some risks were worth taking.

That said, it was an easy day. The library opened at nine and, until the first reading group arrived an hour later, Alsop and the library staff usually had the place to themselves. Plenty of time for tea and toast before the lunatics arrived.

And that morning he even had a plan. He would read his paper then wander across to the deli for some Alston cheese. One of the librarians was going to teach him how to make a soufflé. And Alsop reckoned baking a cheese soufflé for his long-suffering wife would be the perfect way to soften her up before telling her about his proposed golfing trip to Portugal.

It was a good plan.

But the thing about plans is that they can turn into a bag of turds in the blink of an eye.

At first he thought the girl was doing the walk of shame, sloping back home after a night in someone else’s bed. She wore a woollen hat, a plain, long-sleeved T-shirt and black leggings. She was limping, her progress uneven and faltering. Her cheap trainers scuffed on the carpet.

She stood in the middle of the library and looked around. She didn’t seem to have any particular book in mind. Her eyes ran over children’s fiction, then local history, then autobiographies. Probably a ruse so she could use the toilets. A quick wash, maybe a line of coke, then a taxi back to Carlisle. Alston didn’t have a resident student population but parties still happened.

But … for most of his career Alsop had been a beat cop in Carlisle city centre and he still had all the right instincts.

Something was a bit off.

His initial assessment had been wrong. The girl didn’t look ashamed, she looked scared. Her eyes flitted back and forth, searching for something. She squinted through the dust floating lazily in the air, never settling on any one thing for more than a second. But the books, neatly arranged, spines out and in alphabetical order, weren’t holding her interest. She was checking out the library staff, dismissing each one as soon as she laid eyes on them.

When she saw him, Alsop knew his morning was no longer going to be about baking the perfect soufflé. He was the reason she was there. She limped over to his desk, her face contorting with the effort. She stood in front of him, draping her left arm across her skinny frame and grabbing her right elbow. Her head tilted to one side. It would have been cute if it weren’t so disturbing.

‘Are you the police?’ Her voice was flat.

‘Not all of them, no,’ he replied.

She didn’t smile at the flippant remark. Didn’t respond at all. Alsop studied her, trying to get a clue, a heads-up as to what was about to happen. Because he was under no illusion: something was about to happen.

The girl was exhausted. Her tired brown eyes were set back in bruised, shrunken sockets. The hair that poked out from underneath her hat was tangled, limp and lifeless. It framed a harsh face. Her pallid cheekbones were pronounced and the grime on her skin was broken by tear tracks. White gunk had formed around a mouth surrounded by spots. And she was skinny. Not skinny in a fashion model kind of way. Gaunt. Malnourished.

Alsop walked round to the other side of his desk, pulled out a seat and offered it to her. She sank into it gratefully. He returned to his own seat, steepled his fingers and rested his chin on them. ‘Now, love, what can I do for you?’ He was an old-school cop and had no use for the gender-neutral forms of address he was supposed to use.

She didn’t answer. Just stared through him. He may as well have not been there.

That was OK, though. He was used to dealing with the public and knew that people gave up things in their own time.

‘Tell you what, why don’t we start with an easy one? Why don’t we start with your name?’

She blinked and seemed to snap out of whatever trance she’d been in, but it looked like the concept of a name was alien to her.

‘You know what a name is? Everyone’s got one, right?’

She still didn’t smile.

But she did tell him what she was called.

And Alsop knew he was in trouble.

They all were.

An old Cherokee said to his grandson who’d come to him filled with hate for someone: ‘Let me tell you a story. I too have felt hate for those who have done me wrong. But hate wears you down and does not hurt those who have hurt you. It is like taking poison and wishing your enemy would die. I’ve struggled with these feelings many times. It is as if there are two wolves inside me, fighting to dominate my spirit. One wolf is good and does no harm. He lives in harmony with everyone around him, and he takes no offence when none is intended.’

‘What about the other wolf, Grandfather?’

‘Ah,’ the old man replied. ‘The other wolf is bad. He is filled with anger. The smallest thing sets him off into fits of temper. He cannot think properly because his anger and hate are so great. And it is a helpless anger, for it cannot change anything.’

The boy looked into his grandfather’s eyes. ‘Which wolf wins, Grandfather?’

The old man smiled. ‘The one I feed.’

Detective Sergeant Washington Poe had been thinking about the old Cherokee fable recently. All his life he’d been feeding the bad wolf. He’d thought he’d known why. His mother leaving him when he was an infant had made him an angry child, and the feeling of abandonment had never disappeared. It had occasionally grown fainter, but rarely long enough for him to make it through a whole night without bolting awake, trembling.

And now he knew that his anger had been based on a lie.

Poe had been conceived when his mother was raped at a diplomatic party in Washington, DC. She hadn’t abandoned him at all. And, like a warning label, she’d named him Washington so she’d have the courage to leave. She was terrified she wouldn’t be able to hide her revulsion when the image of her rapist began to appear on her son’s face.

The man who had raised him, the man he’d called Dad for nearly forty years, wasn’t his biological father. That honour belonged to someone else.

Since he’d discovered the truth, his anger and resentment had morphed into a white-hot rage, a burning need for retribution. That his mother had died before he’d found out added to his sense of raw injustice. Something inside him had crumbled to dust recently.

For a while, he’d had the distraction of the Immolation Man Inquiry. He’d been a key witness and had spent days giving evidence to committees and at public hearings. But now it was over. Poe’s testimony, along with the evidence that he and everyone else involved in the case had uncovered, had ensured the right result: the Immolation Man’s story was verified and in the public domain. Poe had won but it was a hollow victory. What he’d learned about his mother had blunted any satisfaction of a job well done.

Someone asked him a question and he jolted back to the present. He tried to focus on what was happening. He was representing the Serious Crime Analysis Section at a departmental budget meeting. It took place every three months and, for reasons long forgotten, it was always on a Saturday. Section heads usually attended it, but when he’d been the temporary detective inspector he’d delegated the duty to his detective sergeant, Stephanie Flynn. When she’d taken over the DI reins on a permanent basis, and their roles had been reversed, she’d taken a perverse delight in doing the same to him. Now he had to go to London every quarter, not her. He didn’t appreciate the irony, although he did like being a sergeant again. It was the optimum balance between power and responsibility. And being an inspector had never sat well with him. The rank always sounded as though it should be prefaced with ‘ticket’, or ‘lavatory’.

‘I’m sorry, what?’

‘We’re discussing quarterly projections, Sergeant Poe. DI Flynn has asked for a three per cent increase in SCAS’s overtime budget. Do you know why?’

Poe did. He usually didn’t. Usually he kept his mouth shut and relied on Flynn’s paperwork being thorough enough to not warrant further examination. He picked up the document. It fell to pieces. Poe silently cursed the admin assistant who’d prepared it for him. If papers were supposed to be together, then staple them. Paperclips were for hippies and people with commitment issues. He gathered them up but couldn’t tell if they were in the right order. The words and page numbers were a blurry mess. He removed his reading glasses from his top pocket. They were a new thing. A reminder that he wasn’t a young man any more. Not that he needed reminding – these days he clicked when he walked. When he found himself holding documents farther and farther away from his eyes, he decided to take the plunge and get tested. Now he couldn’t drink coffee without his glasses steaming up. He couldn’t lie on his side and read in bed. He’d forget they were there and knock them off. He’d forget they weren’t there and jab himself in the eye when he tried to adjust them. And no matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t keep them clean.

He rubbed them on his tie now. He might as well have wiped them on some chips. He squinted through the smudge and familiarised himself with the document.

‘It’s because of the Immolation Man case. Myself, Analyst Bradshaw and DI Flynn were in Cumbria for some time and most of the OT budget was used up. She wanted to spread the cost rather than hit you with a large deficit at the end of the financial year.’

‘Makes sense,’ the meeting’s chair said. ‘Anyone want to add anything? I suppose we could argue that it falls under the LOOB provisions.’

By the time Poe had failed to locate LOOB in his internal database of nonsensical acronyms, the discussion had moved on to an additional funding request from the transnational organised crime unit. They were struggling to cope with the threat of Entity B. Not a lot was known about them. They didn’t run bouncers or women. They didn’t have dealers on street corners. They did, however, control the supply routes the underworld used. If a Chinese illegal was working off debt in a south London brothel, the chances were it was Entity B taking the biggest cut of her takings. If a mid-level heroin supplier in Arbroath was cutting his product with brick dust, then the pure stuff almost certainly came from an Entity B supply chain. If another Russian state-sponsored assassination occurred on British soil, it was likely the killer had been smuggled in and out of the country by Entity B.

But … managing Entity B was someone else’s job. His was to catch serial killers and help solve apparently motiveless crimes. Something he hadn’t spent too much time thinking about lately. He stopped himself subsiding back into thoughts of revenge and retribution. He didn’t want to keep feeding the bad wolf. Instead he turned on his phone to see if there were any news alerts about Storm Wendy. It was all the media were talking about. A summer storm was rare. A storm of this supposed magnitude was a once in a generation event.

While he waited for his BlackBerry to power up, he examined his reflection in the blackened screen. A sullen, grizzled face with bleary, bloodshot eyes squinted back – the inevitable by-product of neglect, insomnia and self-pity.

The screen changed from black mirror to colourful apps, most of which he didn’t recognise and wouldn’t use if he did. He had three missed calls and a text message, all from Flynn. He was on-call so should have had his BlackBerry switched on, but in the National Crime Agency if you got a reputation for answering your phone, it never stopped ringing. He read the text: Call me as soon as you get this.

That didn’t sound good. Poe made his excuses and left the room. The office manager directed him towards an empty desk. He dialled Flynn and she answered on the first ring.

‘Poe, you need to contact Detective Superintendent Gamble immediately. He’s waiting for your call.’

‘Gamble? What’s he want?’

Gamble worked for Cumbria Constabulary and had been the senior investigating officer on the Immolation Man case. He’d been demoted one rank when the dust settled and the finger-pointing began. Poe knew Gamble considered himself lucky to still have a job. Although they hadn’t always seen eye-to-eye, they’d parted on good terms. Their paths had crossed occasionally during the inquiry, but it was over now. There was no obvious reason for them to talk.

‘He wouldn’t tell me, which makes me think it may not be about the Immolation Man,’ Flynn replied.

Poe had left Cumbria Constabulary five years ago. His home was still there but if anything had happened to it, it would be a uniformed constable from the Kendal station calling, not the superintendent from Major Crimes. And anyway, his home was four solid walls of unrendered Lakeland stone, a slate roof and not much else. There wasn’t really anything that could happen to it.

‘OK, I’ll call him.’

She gave him Gamble’s number. ‘Let me know?’

‘Will do.’

Poe hung up and dialled Gamble. Like Flynn, he answered on the first ring.

‘Sir, it’s DS Poe. I got a message to ring you.’

‘Poe, we have a problem.’

Poe, we have a problem. Five words he never tired of hearing.

Flynn had arranged for him to get the first available train to Cumbria. He had an hour before it left. The tickets would be waiting for him at Euston. He had no idea what was up; Gamble wouldn’t tell him anything more over the phone.

Poe made his train with fifteen minutes to spare. London to Penrith was just over three hours and he spent the time on his phone, searching for anything in the news that might hint at what he was about to step into. He found nothing out of the ordinary. Storm Wendy continued to dominate the local and national press. It was still a week away but had already wreaked havoc on the other side of the Atlantic.

A uniformed officer waited for him at Penrith and he was whisked off to Carleton Hall – Cumbria Police’s headquarters building. Ten minutes later he was taken to Conference Room B. It was a large room, full of character. Poe thought it might have once been the Carleton family’s dining room. It had the original, ornate fireplace, a carved mantelpiece and tall, impractical windows. A long conference table dominated the room.

Detective Superintendent Gamble was already there. A detective Poe thought he remembered from his days on the local force sat beside him.

They both looked up. Poe got the impression he’d interrupted something. The detective’s expression was flat and neutral. He had a large file in front of him. He closed it and put it face down.

Poe nodded a hello. Gamble returned it, the other man didn’t. Gamble stood and shook his hand. Poe noticed him glance down.

‘How is it?’ Gamble asked.

The skin on Poe’s right hand was shiny and scarred. A permanent reminder of what happens when you grab a cast-iron radiator in a house fire. He’d been trying to get the Immolation Man out of a burning farmhouse at the time. He flexed it and said, ‘Not bad. Got most of the feeling back.’

‘Coffee?’

Poe declined. He’d already had too much and he was feeling jittery.

‘I think you already know DC Andrew Rigg,’ Gamble said. ‘He has some questions about one of your older cases.’

Rigg had been in uniform when Poe was with CID. Tall and gangly, with buck teeth that occasionally earned him the nickname Plug, Poe remembered him as a solid cop.

‘What’s going on?’

Rigg wouldn’t meet his eyes, which was strange. They’d never been friends but there’d never been hostility between them.

‘Tell me about the Elizabeth Keaton investigation, Sergeant Poe,’ he said.

Elizabeth Keaton …

Why wasn’t he surprised?

‘It was the last major case I worked up here,’ Poe said. ‘Started as a high-risk missing person. Her father had called 999 from his restaurant. He was in hysterics saying his daughter hadn’t returned home.’

Rigg looked at his notes. ‘It was a suspected abduction?’

‘Not immediately.’

‘Not what it says here. According to the file, abduction was discussed very early on.’

Poe nodded. ‘The file says that because it’s what Jared Keaton was saying.’

Gamble’s brow furrowed. ‘I was attached to the Met back then, and I don’t want to second-guess what happened, but might there have been some pandering? We don’t usually let relatives dictate our lines of enquiry.’

Shrugging, Poe said, ‘Most relatives don’t cook for the prime minister.’

At the time of his daughter’s disappearance, Jared Keaton was the owner of Cumbria’s only three-Michelin-starred restaurant: Bullace & Sloe. He was a celebrity chef who counted film stars, rock icons and ex-presidents as his patrons. He’d cooked for the Queen and he’d cooked for Nelson Mandela. When a chef with three Michelin stars spoke, important people listened.

‘So it was pandering?’

‘No. The file said what Keaton wanted it to say. We investigated Elizabeth Keaton’s disappearance the same way we would every other young girl’s: seriously and with an open mind.’

Gamble nodded, satisfied with Poe’s explanation. ‘Go on.’

‘She should have called him for a lift back from the restaurant, but he’d fallen asleep watching the television and hadn’t woken until the early hours. It was then he noticed that she hadn’t returned home.’

‘She worked there?’

‘Front-of-house and accounts. Dealt with suppliers and the payroll, that type of thing. She was also responsible for closing up at the end of the night.’

‘She was still a teenager. Wasn’t she a bit young for all that responsibility?’

‘You know her mother died in a car crash?’

Rigg nodded.

‘She took over from her.’

‘So, she never called him for a lift?’

Poe knew the file was thorough. Knew that Rigg was doing what every good cop did: asking questions to which he already knew the answers. It still rankled, though. The investigation might have headed down the wrong road initially, but it quickly about-turned.

‘Not according to Keaton. He said the phone would have woken him.’

‘Bullace & Sloe was only a short . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...