The Thousand Eyes

I doubt South Jersey’s ever been called The Land Where No One Dies, but according to my painter friend, Barney, who lives near Dividing Creek on the edge of the marshland leading to the Delaware, back in the early ’60s—out there amid the two mile stretch of cattails, quaking islands, and rivulets—there was a lounge called The Thousand Eyes, and there was a performer who sang there every Wednesday night, advertised on a hand-painted billboard along the northbound lane to Money Island as Ronnie Dunn, The Voice of Death.

Barney heard all about it from another local painter, Merle. Old Merle was getting on in years, and I’d see him, myself, when driving through Milville, creeping along the sidewalk in his tattered beret, talking to himself. He swore that his apartment was haunted. Still, Barney said he never doubted what Merle told him. The reason he trusted him was that a few years back he’d asked him if he’d ever been married. The old man said, “Once, for a few months, to a charming young blonde, Eloise. It lasted through spring and summer, but come fall she up and fled. Left me a note, saying my breath stinks and my dick’s too small.” Barney vouched for the former, and then added “Do you think somebody who’d tell you something like that would lie to you?”

Anyway. Merle was in his late 20s and it was 1966. He was living by himself in the top-floor apartment of a half-abandoned building in the town of Shell Pile. Even though the floorboards creaked, the paint curled, the windows let in the cold, and every hinge groaned, the place was big, with plenty of room to paint and live. He scrounged together an existence between doing odd jobs around town and working a few shifts when he had to loading trucks at the sand factory. If he had to travel any distance, he rode a rusted old bike with a basket and pedal brakes. He ate very little, twice a day, and blew most of his income on cigarettes, liquor, and weed. The most important thing to him was that he had plenty of time to paint. As long as he had that, he was happy.

At the time, he was working on a series of paintings depicting the bars in South Jersey. He’d go to one, have a few drinks, take some shots with his Polaroid Swinger and then go back to his place and paint an interior scene with patrons and barkeep, bottles and bubbling neon signs. Barney explained Merle’s style as “Edward Hicks meets Edward Hopper in a bare-knuckle match.” Still, he was a hard worker, and before long he’d been to all the bars in the area and painted scenes from each. He liked the individual paintings in the series, but overall he felt something was missing.

Then one day when he splurged for lunch and had a burger and fries at Jack’s Diner, served as they always were back then on a piece of wax paper instead of a plate, he overheard the conversation of the old couple in the booth behind his and realized what it was that was missing from his series.

“The Thousand Eyes,” he heard her say, and instantly it struck him that he’d not painted it.

“I heard it’s impossible to get to,” the old man said.

“Nah, I had Doris at the liquor store draw me a map.”

“That’s where you want to go for our fortieth, some mildewed old cocktail lounge sinking into the Delaware?”

“I want to hear that singer who’s there on Wednesday night, Ronnie Dunn. He’s got a record that they play on the local station ‘Fond Wanderer.’”

“Wait a second,” he said. “That’s the ‘word of doom’ guy.”

“The Voice of Death.”

“Who wants to hear the voice of death?” he said.

“You know, it’s a gimmick. Mysterious.”

Their food came then and Merle paid and left.

He’d heard about the Thousand Eyes since he’d moved to Shell Pile, but he’d never been there. It advertised only late at night on the local radio with a snappy jingle, “No one cries at the Thousand Eyes.” The place came up in conversation around town quite often, but he’d only met a handful of people who’d actually been. The shift manager at the sand factory told him, “I drank out there one afternoon during low tide. If a shit took a shit, that’s what it would smell like. I almost hallucinated.”

There was a woman he met at one of the bars he was photographing who told him that she heard, and now believed, that only certain people were called to see Ronnie Dunn perform. The singer sent out secret invitations through his song on the radio. If one was for you, you would find the Thousand Eyes; if not, you wouldn’t. “I’ve been out there three times with my girlfriends, and three times we got lost,” she said. “A couple of people supposedly went to look for it and never came back.”

“Is that true?” asked Merle.

“I guess so,” she said.

Luckily, Doris at the liquor store didn’t mind at all drawing Merle a map.

So on a Wednesday night in September, he took off on his bike, camera around his neck, pedaling west toward the river. Doris figured by bike the trip would take him about an hour and a half. He was to look for Frog Road off Jericho, and then head west following Glass Eel Creek, looking for a spot where a packed-dirt path led off on the right into the cattails and bramble. She told him the Army Corps of Engineers built the road back in the early ’50s when they were trying to eradicate mosquitos. The sunset was rich in pink and the weather was cool. Merle rode fast, excited by the prospect of finally finishing what he’d started.

He found the path and took it out into the marsh, cutting through stretches of cattail, stretches of soggy earth dotted with green. He passed into a small wood, all its trees twisted and stunted by the salt content in the water. Stopping and resting for a moment, he took a deep breath. The call of mourning doves and the breeze in the dying leaves gave him a chill of loneliness. As he got back to pedaling, he wondered how lonely it would feel there in the dark on the way home. On the other side of a clutch of white sand dunes, he descended and crossed a wooden bridge over what looked like deep water. Beyond it sat the Thousand Eyes, majestic in its grandiose molder. A Victorian structure with a wraparound porch and a splintering wooden cupola over the entrance.

The dirt path became the dirt parking lot of the place. Situated at the spot where one turned into the other there was a large sign held up by two 4x4’s planted in the ground. The only writing it held was in the very bottom right corner; otherwise it was a big rectangle of eyes on a violet background. Carefully rendered peepers of all sizes with lids and lashes, staring, squinting, popping and red, sad and blue. In the corner it said, “These one thousand eyes were painted by Lew Pharo.” Pharo was one of the local painters, and Merle knew him. He couldn’t recall Lew ever speaking of this job, though.

Beneath the signature, there was a vertical list in smaller script—No Bare Feet, No Pets, No Foul Language, No Spitting, No Cameras! Merle hid his bike in the cattails at the edge of the parking lot and then took his jacket off and wrapped it around the camera. Darkness swamped the marsh as he took the splintered steps to the entrance. He opened the glass door, and when he closed it the sound echoed through the place. His footsteps set the floorboards to squealing down a dim hallway. Off to his right, he saw a pair of doors flung open on a large room lined on two sides by windows. A lit tea candle sat on every table, and beyond there was a dance floor and a low stage with a curtain behind it. As he entered, the bar came into view off to the left.

There was a guy behind it wearing a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up and a black bow tie. He had a lit cigarette in the corner of his mouth. When he caught sight of Merle, he called in a puff of smoke, “Step right up.” An older man and woman sat at the bar, drinking martinis. “What’ll it be, sailor?” the bartender said.

“Vodka on the rocks,” said Merle.

“A purist.”

“Is Ronnie Dunn performing tonight?”

The woman turned and said “Yes” before the bartender could answer.

Merle wondered if the old couple were the same people from Jack’s Diner. His drink came and he said, “So, did you name this place after the Bobby Vee song?”

“This place has been here long before that song ever came to be,” said the bartender. “In fact, that song was written by two women and a guy. The guy, Ben Weisman, who wrote songs for Elvis and dozens of other stars, came in here one night, and that’s where they got the title for ‘The Night Has a Thousand Eyes.’”

“For real?” said Merle.

“Yeah, there was this housewife from Passaic, Florence Greenberg, who started a record company around 1960, Tiara Records. She was on vacation down here that summer, visiting relatives, and Weisman flew into Philly and drove down here to try to sell her some songs for her artists. Greenberg’s niece, Doris, gave them directions to the Thousand Eyes as a place to get away, and they spent the afternoon into the night, doing business right at this bar. I was tending bar that night, and I clearly remember Weisman at one point asking Greenberg, ‘What rhymes with eyes?’” The bartender took a deep drag on his cigarette to emphasize the profundity and blew it out at the ceiling.

After another round had been served, the bartender said, “You folks better get your seats for the show. It’s gonna get crowded in here in a few minutes.” Merle thanked him, took his drink and balled-up jacket, and chose a table set off in the back by the wall from where he could take the whole scene in at once. He sat there, staring into the light of the candle on the table, sipping his vodka, feeling for the first time the damp chill of the place, when a thought popped into his head. First it struck him that he hadn’t seen Lew Pharo in a long while, and then came the memory flash that Pharo was, in fact, dead. It all came back—Lew had suddenly gone blind, couldn’t paint, and shot himself in the head.

He smelled low tide, heard the cars pull up in the parking lot. The patrons shuffled in. That night the Thousand Eyes drew six couples in rumpled finery, a pair of girls a little younger than Merle, a creepy-looking guy with a wicked underbite, and a crazy woman in flowing pink gauze who danced to her chair. A waiter appeared and took orders. Merle was still trying to figure out, since he had to use the flash, how he was going to get a shot. He wondered how serious they were about No Cameras.

By 8:30, everyone was juiced. The waiter had been twice to Merle’s table and the bartender put on the jukebox a string of Jay Black and the Americans tunes. The crazy lady in pink and the guy with the underbite took to the dance floor and did a dramatic fake tango to “Cara Mia” and everybody applauded. Finally at 9:00, the house lights went down, and then out. A few moments later a spotlight appeared on the 12-inch raised platform at the edge of the dance floor. It was the waiter with a microphone hooked to a small sound system strapped to a hand truck. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said into the mic, which sparked with feedback, “now the moment you’ve all been waiting for.” While he spoke, two guys rolled a very small piano onto the stage from behind a curtain.

The waiter stepped forward as they brought out a drum set. “As some of you might know, there’s an old Romanian tale about a man who, late in his life, becomes wealthy. This fellow thinks it’s a shame that he won’t live long enough to spend all of his money. His rich friends tell him he should go to The Land Where No One Dies. So he does and takes his wife and daughter with him. Everything there is smooth as silk, plenty of sunshine, plenty of booze, no hangovers. What’s not to love? But then the wealthy man finds out that although no one dies, occasionally someone hears a persistent voice calling them. When they follow it, they never return. He realized this must be the voice of death. When his daughter hears its call, he tries to stop her from following it but he fails. The voice is just too compelling.”

The waiter stopped for a deep breath and then said, “Renowned critics, ladies and gentlemen, have likened the allure of our special guest performer’s voice to the voice in that very tale. So let’s hear it for RRRRRRonnie DUNN, the Voice of Death.” The guys moving the instruments had become the band—a bass, piano, electric guitar, and drum. They played “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” and the stage filled with fog. It crept up around the legs of the players and billowed out onto the dance floor. When it cleared, there stood Ronnie Dunn, mic in hand. The band switched course into the intro for “Fond Wanderer.”

Barney quoted to me Merle’s first-hand impression of the singer. “It looked like they dredged him out of the river. Gray complexion, and kind of barnacles all over his neck and face. His hair was white going yellow like an old wedding dress, and he wore it in a moth-eaten wave. The tux was too tight. Ronnie wasn’t just Dunn, he was well done.” Still, he slowly lifted the mic and sang.

Fond Wanderer, where do you go?

Fond Wanderer, I know you don’t know.

Fond Wanderer, come to me now,

Step into the shadow, and I’ll show you how.

Merle described Dunn’s voice as, “If you took Little Jimmy Scott and Big Ed Townsend and sandwiched Johnny Ray between them and then lit the whole fucking thing on fire, it’d be a little like that.” He said Ronnie was out of tune and behind the count, low, menacing, but sometimes he’d hit a few sweet and beautiful notes. There was a rich resonance to its sound before it even hit the twang of the tinny speaker, like a song echoing down through a metal pipe from some strange other place. Off-putting at first, then intriguing, and eventually its appeal was hard to resist.

Fond Wanderer, please hear my plea.

Fond Wanderer, you can’t ignore me.

Fond Wanderer, it’s over and out,

More like a whimper, less like a shout.

Ronnie creaked around with some mortuary footwork between stanzas and then hopped off the stage and approached the table with the two young women. “You girls busy tonight?” he said into the mic. The band waited for him, keeping the tune going. “Step into the shadow,” he said, “and I’ll show you how.” The young women grimaced, got up and left. The crowd loved it.

Fond Wanderer, can I have this dance?

Fond Wanderer, are you sleepy by chance?

Fond Wanderer, this way’s the door,

Out to the boat waiting down by the shore.

Merle heard the song on the radio enough to know there was another stanza coming. He got the camera and put his jacket on. His strategy, born from momentary intuition, was to approach from the right, sweeping around the tables to that side and getting close to the stage from where he could capture Ronnie, some of the patrons on the dance floor, and the reflection of the tea candles off the mirror and bottles behind the bar. He moved without hesitation.

The flash made the singer lift his arm in front of his eyes and stagger backward, shrieking like a gull. In the fifteen seconds Merle had to let the film develop before he could rip it off and peel it open, the band stopped playing and Ronnie lurched through the spotlight. “You’ve ruined it,” he screamed, going green in the face. Dust fell out of his nose and his hair wave had broken. Abruptly he stopped, looked across to the bartender and yelled, “Don’t just stand there, get the camera. Come on.” The bartender waved to the guys in the band and they put down their instruments and stood up. Merle ran.

He brushed past the couples on the dance floor and was heading toward the double doors. ...

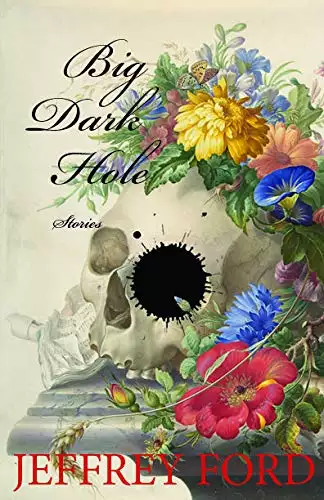

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved