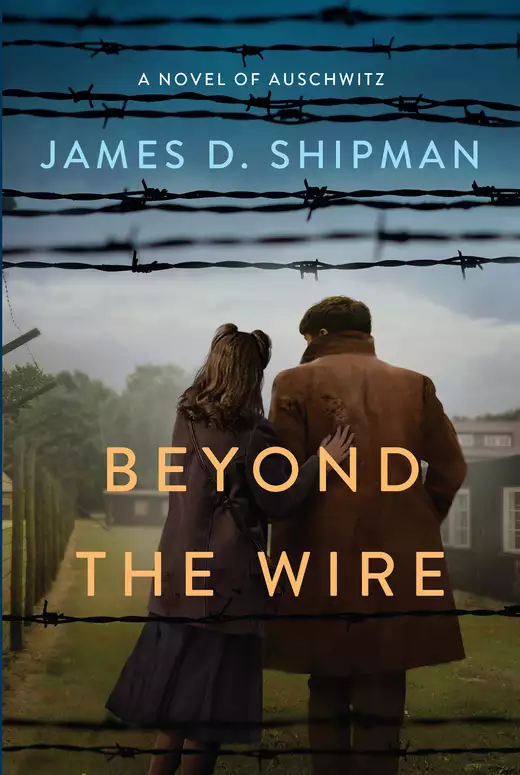

Beyond the Wire

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

October 1944: In the long, narrow undressing rooms in Auschwitz-Birkenau, prisoner Jakub Bak toils under the scrutiny of SS guards. Like other members of the Sonderkommando, Jakub was selected on arrival for an unthinkable job: sorting through the clothes of the dead and moving their bodies from the gas chambers to the crematoriums. Jakub clings to the promise he made to his murdered father—to live, at any cost—and to the moments he is able to spend in the company of Anna, imprisoned in the women's camp.

Every morning, Anna marches miles to the union munitions factory where she works alongside other prisoners. Even Jakub doesn't know that she and a few other women have been taking the ultimate risk, smuggling trace amounts of gunpowder back in their clothing. A bold plan is brewing to revolt against the SS and liberate the camp. Jakub, pressured to join the resistance, knows that any uprising faces impossible odds. Added to this already stark choice is another desperate reality—the risk from informers who see their only chance of survival in betraying their fellow Jews.

Powerfully moving and unflinching in its authenticity, Beyond the Wire tells of the women and men who, though outnumbered and outgunned, fought to free themselves, sparking a brilliant flash of light and hope amidst the darkest evil that humans can conceive.

Release date: January 25, 2022

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Beyond the Wire

James D. Shipman

He was so thin that his frame felt stretched, his skin translucent like paper. He looked over his matchbook arms swimming in an ocean of sleeves. Jakub reached up and ran his hand over his head, feeling the stubble. He’d possessed a mop of unruly reddish-brown hair, but it was gone, shorn off by the Nazis— who needed it for the felt slippers of U-boat crews, or some such madness. Another casualty of this hell.

All quiet now. The Zyklon B had done its work. Another thousand candles snuffed out. He shook his head. Mustn’t think of that right now. When his clothing stack was head high, he jerked the pile from the bench and stumbled to a nearby cart, easing the cumbersome load inside. If the fabric toppled over, he’d have to start again, and he might get a beating for it if a guard was nearby.

Schmidt was here today. The worst German of all. He looked like a child in his SS uniform. He was missing his upper middle teeth and his words whistled and slurred when he spoke. His cheeks were deeply pocked. When Jakub had first arrived in Auschwitz, he’d felt sorry for the man’s unpleasant features. That hadn’t lasted long. On the first day he’d watched the SS sergeant shove two workers into the gas chamber—killing them just for fun in a game the Nazi called “the lottery.” He played it most days he was stationed here. Jakub wished that Schmidt were all he had to worry about, but amusements were just one of a thousand ways to die.

Up and down the long, narrow undressing room, the Sonderkommando labored, each prisoner rushing about, head down, avoiding the attention of the SS.

“Hurry up, you worms!” shouted Schmidt. “There’s another group waiting. Get things put away double-quick or I’ll send the lot of you in for your own special treatment.”

Jakub dashed to another stack, eyes on his feet. The room was nearly cleared out now. He clutched the handle of the cart when he was finished and struggled toward the door. Another prisoner hurried up, crashing into him and nearly knocking him over. It was Tomasz.

“I’m not letting you take all the best jobs,” his friend whispered. “Still alive I see.”

“I am,” whispered Jakub. “But for how long? Only God knows.”

Tomasz chuckled grimly. “Always the philosopher. You’re still breathing this moment, that’s what matters. Tomorrow you could be up the chimney, so why worry?”

“I’m going to survive this,” insisted Jakub, gritting his teeth.

“Sure you will, boy, sure you will. If anyone can, it’s you. As for me, I’m just trying to live until tonight.” Tomasz leaned in closer, looking up at his friend. He wasn’t much older than Jakub, but he had the fierce, weathered features of a Warsaw tough. “Do you have anything?”

“A watch. A little money. I couldn’t count it.”

“The watch any good?”

“Gold, I think.”

Tomasz whistled. “That alone will get us through. And a bit more than that.”

“How are you fixed?”

Tomasz smiled. “It’s been a good morning. I’ve got three gold coins. Good-sized ones. Old Russian ones I think. A couple biscuits too. I’ve one for you when we get around the corner.” They pushed the cart through a set of double doors and turned to the left. For a few seconds they were unobserved, and Tomasz shoved his hand in Jakub’s pocket, leaving behind a lumpy object.

“Thanks, I’m starving.”

“Aren’t we all, my boy? But we manage a hell of a lot better than those poor bastards in the main camp.”

Jakub nodded. “And they hate us for it, and for handling the living and the dead.”

“Bah,” scoffed Tomasz. “What choice do we have? I don’t remember filling out an application, do you? They can get all high-and-mighty about what we must do, but that’s not why they dislike us. It’s our access to things that help us survive that they hate.”

“I’d be dead already without the extra food,” admitted Jakub. “Still, that might be better than living like this.”

“There you go again, thinking. No good doing any of that in here. It’s grab the goods, eat what you can, and trade for a little fun. No point worrying about anything beyond that. A bullet or that gas yonder is just a mistake away.”

“Speaking of that, Schmidt’s in a mood today.”

“Watch that one,” warned Tomasz. “He’s a snake inside a wolf inside a demon.”

“He looks half devil,” said Jakub.

“More like a rat to me. But one with a deadly bite.”

They reached the end of the corridor and pushed the cart up a ramp to the outside. The undressing room and gas chamber in Crematorium II were located in the basement, necessitating a laborious trip up to the ground floor. They couldn’t talk now because there were guards present. They strained at the weight of the thing as they shoved it up, spurred by the shouts and orders of the waiting SS. They reached the top and recovered their breath for a moment as one of the Germans picked at the stacks with a baton. After satisfying himself that there was nothing smuggled inside, he ordered Jakub and Tomasz to load the clothing into a waiting truck. They moved on the double-quick, stacking the articles in the back. Fortunately, the bed was nearly full, so they didn’t have to climb in and out. In a few minutes they were done, and they scurried down the ramp with the encouragement of a couple blows to the back from the Germans who screamed at them to hurry.

“I hardly feel them anymore,” muttered Tomasz. “The bastards.” He leaned closer and whispered, “The Russians will hit these Nazi pricks even harder, I think.”

“If they ever get here.”

“They will. Have faith. But whether we are alive or just some dust by then, that we will have to see about.”

They reached the basement and pushed through the doors to the undressing room. There was already a new group of arrivals there, starting to undress. Jakub hesitated.

“What are you doing?” Tomasz asked.

“I don’t want to go back there. Can’t we wait?”

Tomasz looked around. “Too risky. Maybe if Schmidt wasn’t there today. But that bastard is looking for any chance.” He shoved the cart along. “Let’s go. Just a few minutes and they’ll be gone.”

Jakub reluctantly followed him. The room was crammed with bodies. They were men, elderly, with a sprinkling of young children. Most of them were removing their clothes, unaware of the death that awaited them a few meters away. But there were a few who looked around, fear in their eyes, watching the guards, looking for answers.

“Excuse me,” a well-dressed man said, stepping up to Jakub. He looked like a professor, with his thoughtful eyes and peppered hair. “What’s going on in here?”

“Nothing,” Jakub responded. “It’s just a quick delousing and then you’ll get your work uniform and barracks assignment.”

“Are you telling me the truth?” he persisted.

The man’s eyes were searching his, pleading for answers. Jakub turned away, trying to avoid him, but he felt a hand on his arm.

“Please,” the man said. “I just want the truth.”

“The truth is you better get undressed,” snapped Schmidt, who had noticed the exchange and rushed up to them. He looked Jakub over, his lips curling in a twisted grin. “Perhaps you should do the same, Bak.”

“I’m working, sir,” said Jakub. “This man asked me a question.”

“And that one question took all this time?” asked the SS guard. “You’re going soft, Bak. Surely there are others who can handle this task more efficiently. I think you better join this gentleman for the delousing, since you’ve become such fast friends.”

“Sir, I—”

“Get undressed!” Schmidt shouted, cracking Jakub on the shoulder with a wooden truncheon. “Looks like you just won my lottery for today, Bak.”

“Now, now, sir,” interjected Tomasz, sprinting up to intervene. “I’ve got something important to show you. Something I’ve just come across.”

Schmidt’s face flushed with anger. “Watch it, Lis. Unless you want to go with them.”

“Sir, I know you’re going to want to see this.” Tomasz never raised his voice but spoke in a calm, measured tone, almost a whisper.

Schmidt hesitated, staring hard at Jakub. He could feel his heart threatening to explode out of his chest. The guard took a step toward him, his eyes glaring. Jakub thought he would strike him. Instead, he took a deep breath and turned to Tomasz. “Well, what is it?”

“Not something for prying eyes, sir.”

Schmidt glanced at Jakub for a moment longer, running his fingers along his jaw as if contemplating something. “Fine. Let’s step over to the ramp.” He turned back to Jakub. “Get back to work, Bak, before I change my mind!” he commanded.

Jakub rushed to the clothing, folding madly, his hands shaking. The new group of victims was already marching to the gas chamber. He stacked the fabric, keeping his eyes down. He was too terrified to search the stuff for anything valuable. He’d forfeited another life. How many more times could he dodge death?

His friend returned, standing next to him and grabbing a handful of clothing. “You cost me all that gold,” whispered Tomasz. “Luckiest thing I’ve found in a while. I could have bought a whole sausage and a dozen loaves of bread. You owe me big-time.”

“Thank you,” he managed to say. “You saved my life.”

“No, I saved your life again,” said Tomasz. “You owe me for that as well.”

Jakub thought of the old man, of the room full of people who were just here. Their lives were already expiring in the adjacent chamber. “Perhaps I should have gone with them,” he said. “Truly, Tomasz, I don’t know how much more of this I can take.”

“You’ll endure all that’s thrown at you, until you’re out of chances,” said Tomasz. “You don’t only owe me. Remember what your father made you promise.”

“I don’t want to think of Papa right now.”

“You don’t have to. But don’t forget, our families are gone. Everything that mattered to us is already up that chimney. You’re all I have. You’re like a brother, Jakub. The nearest thing I’ve got left, and I’m not losing you to your brooding guilt. Now get your ass moving! Remember, we’ve the fence to look forward to!”

The work was done. After a half-hour roll call in the frozen evening air, Jakub and Tomasz marched with the others up two flights of stairs to the attic. Long lines of bunks stretched the length of the room. A single stove burned in the corner, emitting a feeble warmth. This would never have kept more than a portion of the space heated, but the crematorium fires below did just that.

Jakub walked over to one of the narrow windows and stared out past the wire that separated Crematorium II from the main camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Row after row of long squat buildings stretched out into the distance. The camp was named Birkenau after the nearby birch trees.

Jakub retrieved a dirty iron bowl from his bunk and marched over with the others to the supper line. A prisoner dished him out a half serving of watery turnip soup and a slice of bread. Jakub returned to the bunk he shared with Tomasz. There was no mattress and no pillow, and they had only a thin blanket to share. He could hardly remember what it felt like to sleep in a real bed. He sat on the edge and was soon joined by his friend.

“Hardly worth the effort, is it?” Tomasz asked, glancing down at their meager supper. He shrugged. “Still, every little bit helps.”

Jakub reached into his pocket and pulled out the biscuit. It was hard as a rock and terribly stale, but he dipped the bread into his soup, softening it for a few seconds before he attempted to eat it. Tomasz retrieved a chunk of salami about the size of two fingers. He tore the meat in two and handed some to Jakub. “There you are, my friend. This will sustain you.”

Jakub shook his head. “That’s for you.”

Tomasz laughed. “Nonsense. Share and share alike between the two of us.” He slapped Jakub on the arm. “If I don’t feed you today, who will I have to bother tomorrow?”

Jakub laughed and accepted the meat. He took half of the piece in one bite, relishing the flavor. He closed his eyes. He remembered his mother’s cooking, the Sunday meals out in Kraków cafés, all the wonderful dishes he’d ever eaten. “Thank you,” he said.

“Don’t mention it. But you’re in charge of the main course tomorrow so you’d better get busy. And don’t forget, you owe me three gold coins and two lives.”

“The gold I should be able to come up with. The lives are a little tougher.”

Tomasz leaned in closer. “Speaking of gold,” he whispered, looking around to make sure nobody was watching them too closely. “Let’s have a look at that watch.”

Jakub retrieved the object from his pocket. It was indeed gold, eighteen karats according to the inscription underneath the dial. The face said Mido from Switzerland. The band was gold as well, a thick, flashy affair that likely came off the wrist of a wealthy businessman.

Tomasz whistled. “Some rich bastard must have been holding on to this. That’s worth more than my coins, I’ll bet.”

“You take it then,” said Jakub, offering it to his friend.

Tomasz shook his head. “Hide it. I know just who to sell it to. We’ll have a feast. We might be able to get ahold of a little booze as well. But I don’t have time to organize that tonight. And for God’s sake don’t bring that to the fence; those Nazi jackals will sniff it out and we’ll get nothing for it.”

“I don’t have anything else except a few zlotys.”

“Don’t worry, I have you covered. I’ll add it to the tab.”

“If we make it out of here, I’ll have to spend the rest of my life paying you back,” said Jakub.

Tomasz shook his head. “No, my boy, a decade should do it.” He looked down at their empty bowls. “Enough of this slop. Shall we get going? The fence awaits.”

Jakub nodded and set his bowl aside. He glanced around for a moment to make sure nobody was looking, then he tucked his gold watch under the middle of the blanket, smoothing it out so nobody would see that something was hidden there. He stood up, arching his back to try to drive out some of the soreness that plagued his back and limbs. He lumbered forward and followed Tomasz toward the door.

He was blocked about halfway across the attic. Two men stepped out into his way.

“Not now,” protested Tomasz. “We’ve an appointment at the fence.”

“This won’t take long,” said one of them, a thick, muscular fellow with a bullet forehead. “The boss wants a word with young Jakub here.”

“Well, Jakub doesn’t want a word with him,” said Tomasz.

“Let him speak for himself.”

Jakub looked at the messengers. They were twice his size. He couldn’t push his way through them and he didn’t want a fight. “I’ll catch up.”

His friend hesitated and then nodded. “I’ll pay the fee up front. You know which guard. He’ll be expecting you.”

Jakub watched Tomasz go. He turned back. “All right, whatever this is, let’s get it over with.”

The men led Jakub back into the far corner of the attic. A figure sat in a lower bunk, conversing with another prisoner. Roch Laska, Jakub recognized him right away. He wasn’t much older than Jakub but it was the facial features that set him apart. Even with shorn hair, he was easily the most handsome man in the barracks, his chiseled features accented by a long red scar extending from eye to chin—a bullet wound it was said he’d caught fighting in the Polish army as a junior officer during the German invasion.

“Ah, Bak, so glad you could join me. Won’t you have a seat?” He offered the place next to him. The other inmate, seeing the gesture, scurried away.

“No, thank you,” said Jakub, on his guard. “I’ll stand.”

“Your decision,” said Roch, shrugging. “Do you know why I’ve asked you to meet with me?”

“I can guess.”

Roch stared up at him for a few moments, rubbing his chin. “You’re a bit of a conundrum to me, Bak, I must admit.”

“How so?”

“Well, I’ve brought this topic up before, but I have to try again. Why won’t you join us?”

Jakub looked away. He didn’t want this tonight. He just wanted to make it to the fence and forget all of this for a little while.

“That’s not an answer,” said Roch after a while. “I’ve watched you a long time, Bak. You’re a hard worker, brave, kind. You’re everything we’re looking for. We’ve already invited you twice, correct?”

Jakub nodded.

“But each time you’ve refused. It’s odd to me. A strong young man like you.” He leaned forward. “To be honest with you, there’s word going around that you might be a coward, or worse yet, a collaborator.”

“I would never work with the Germans.” He felt his face flush and his insides burn.

“Don’t worry,” said Roch, waving his hand as if dismissing the idea. “I’ve had you checked out. We know you aren’t one of those. But what does that mean? Are you a coward?”

Jakub bristled. “I’m not afraid. At least not more than anyone else. I just don’t see the point of your group. That’s all.”

“How so?”

“You say you are going to resist the Germans? With what? You have no weapons, nothing to fight with.”

“You don’t know everything. And we’re working on that.”

“But there’s only a few hundred of us in here. Even if we managed to get ahold of a few pistols or something, it would be suicide to take on the SS.”

Roch nodded. “True enough. But there are thousands in the main camp. Tens of thousands maybe.”

Jakub scoffed. “Those scarecrows. They’re at death’s door. At least most of them are. They’d do no good for anyone.”

Roch’s eyes hardened. “So, we shouldn’t try to save them? You think we’re better than they are? Why, because we can steal a coin or two and feed ourselves? You don’t think we owe anything to anyone else?”

“Look, Roch. I’d join with you if there was a point, but I’m not going to risk my life when there’s no chance it will come to any good. I intend to survive, if there’s any chance to do so. I haven’t joined your group because I think you’re going to all get yourselves killed. And for nothing.”

“That’s your friend Tomasz talking,” said Roch.

“I can make up my own mind.”

“So, you’re just going to keep on taking care of yourself? Waltzing through the camp with Tomasz as if you’re on your way to a Warsaw theater show?”

“I wouldn’t know anything about that, I’m from Kraków.”

Roch smiled. “I see there’s no point with you. At least not yet.” He shrugged, waving his hand in dismissal. “You can go, Bak. But think about what I said. I understand surviving for survival’s sake. But there’s more to the world than our own little skins. We owe something to all those little candles we lead into the gas chamber. And to the scarecrows in the main camp. We are the only men here in decent shape. The only ones who could put up a fight. That gives us power . . . and responsibility.”

“Power? What power?”

“Even a little freedom is something.” He waved his hand at Jakub. “Go on now. Go have your fun. I’m not saying we don’t all deserve a little pleasure in this hell. But think on what I said. And don’t be a stranger, Bak. I’m expecting you to come around. Think on it, will you?”

Jakub nodded. He walked out and started toward the fence. He tried to summon some excitement, but the joy had seeped out of the evening. Roch’s words echoed through his mind. Resistance. He looked at the guards, their automatic machine pistols, holding vicious dogs straining at the leash. What could they do against these men of steel?

As he approached the fence, he could tell immediately something was wrong. The guard, Himmel, whom Tomasz was going to bribe, wasn’t there. There were two SS here, and Jakub wasn’t familiar with either of them. Jakub looked around for Himmel, but the man was nowhere to be found. The guards were eyeing him suspiciously. One of them took a step toward him, mouth half open, ready to question him.

Jakub turned and scampered away as quickly as he could. He expected a shout for him to halt, but none came. He made it back to his building, his heart in his throat. There would be no fence tonight. Roch had held him up too long. He kicked the wall, cursing with frustration. Another day of death and desperation in Auschwitz, and not even the fence to shine a little light on him. He slumped up the stairs to his bunk, damning the resistance and the stupidity of Roch’s reckless hope.

SS Obersturmführer Hans Krupp sat impatiently in the outer office waiting for the Birkenau Lagerführer to summon him. He checked his watch again. He’d already been here a half hour. How dare Kramer keep him waiting this long! The bastard. He suspected he knew what this was about.

Finally, the Kommandant stepped out of the office and fixed Hans with a steely stare. The Birkenau commander possessed criminal features, with squinted eyes and a flat forehead. Hans stood and delivered Kramer the Hitler salute.

“Ach, Krupp, come in. I’m sorry I had to keep you waiting.” His face didn’t look sorry at all. “What can be done about all this paperwork?” he muttered, not putting any real effort into making his excuse carry weight.

Hans followed him into an office in the main guardhouse overlooking the arched “Death Gate.” Hans looked out over the rail line that split the camp. At the far end a kilometer away Crematoriums II and III were partially visible behind the trees. To the left, along the fence line, was the penal company and the infamous Block 25, the “Death Block.” To the right of these were the rows of barracks constituting the women’s camp. Farther on, across the wide gap of the railroad, and occupying a much larger space, were the men’s camp, the Gypsy camp, and the family camp. And beyond them in the far distance were Crematoriums IV and V, along with the buildings where the clothing and personal items of the gassing victims were sorted and collected. This area was called “Canada” by the inmates because of the almost mythical association it had as a place of wealth and treasure.

The rail line itself was the central and focal point of the camp. This was the place where trains unloaded thousands of people at a time. Here they were sorted by an SS officer near the tracks. If he moved his thumb one way, the unlucky person joined the line of about 90 percent of the new arrivals, and would be immediately marched a few hundred meters to Crematorium II or across the tracks to Crematorium III, where they were undressed and gassed. A wave in the other direction and a person had renewed life and would be tattooed and processed into the camp for labor.

Hans thought of this past summer when Kramer had just arrived at the camp. Birkenau at the time groaned under the flurry of activity as the Jews of Hungary arrived and disappeared. Hundreds of thousands of them were liquidated. Nobody knew how many for sure. The new Kommandant had been too busy during this harvest to do much administration within the camp, Hans knew, but recently the transports had slowed down and Kramer turned his eyes inward, looking for new objects of his frenetic attention among the German staff.

The office they sat in now was a modest one. A steel desk was pushed against the wall. Cheap wood paneling covered the walls. An oversized portrait of Adolf Hitler loomed above and behind the chair where Kramer perched. The camp commander thumbed through a file folder with Krupp’s name on it.

“So, you’ve been here since 1942 it looks like? Ja?”

Hans nodded in answer. “I came when the camp was just getting going.”

“You were promoted to head of security in the Birkenau camp in January this last year? Correct?”

“Correct.”

“Hmm. A few months before I arrived. To be honest, I’d like to have made that decision myself, but we don’t get everything we ask for.”

Hans ignored the implied insult. “You came at a chaotic time, sir. What with the Hungarians arriving in droves.”

“I doubt you could find a Jew in all of Hungary today,” joked Kramer. “Colonel Eichmann did his work well.”

“He always does.”

“Which brings me to your work.” Kramer frowned over the paperwork, running his finger down some official report. “Ah, yes, here it is. I want to talk to you about this Edek and Mala escape.”

Hans thought this might come up. “What about it, sir?”

“I read the details. A messy business. It seems there were a lot of inmates involved. Prisoners with low numbers. And hints that some of our own men might have helped them.”

Hans knew what Kramer meant by low numbers. Each permanent inmate, those who were not immediately gassed, was given a sequentially numbered tattoo. Inmates with low numbers, often a German criminal or non-Jewish Pole, were people who arrived in the camp several years before and had managed to survive the almost impossible conditions in the camp. These men, and some women, now formed a kind of camp elite.

“Well, Krupp? Were SS involved in the escape?”

“Only rumors I’m sure, sir.”

“Perhaps. But how did the two of them manage to get so far?”

Hans shrugged. “The camp complex is huge, sir. Some of these prisoners have been around a long time and have garnered quite a bit of influence. Given enough time, it’s not surprising what they figure out. And I would point out, sir, they were caught after all.”

“Yes, they were, but I’m not worried about the last escape, I’m concerned about the next one. You’re right about the prisoners. There are far too many of them, and a troubling number who’ve managed to make it so long. Still, that’s a problem we will sort out in the long run. What I’m focused on today is the astounding lack of progress that you seem to have made in infiltrating their numbers.”

Hans hadn’t expected this. “What do you mean, sir?”

“I’m talking about spies, Krupp. With so many influential prisoners, why don’t you have more informants? I don’t want to find out about escapes after they happen. I want to catch prisoners before they’ve even acted. That way, nobody will be tempted to even try it.”

“We always have a system of informants, sir. However, they tend to ferret out the snitches,” responded Hans. “And they dispose of them.”

Kramer’s face reddened. “So, the prisoners run things here? Is that it? I don’t care what happens to these little weasels. But we need the information. I don’t want to hear that they are killing off informants so we can’t get what we need. If one dies, secure two more. Good God, Krupp, they are starving and they have no possessions. There is no hope of them ever leaving here. How hard is it to get a few of them to squeal in exchange for a little food or protection?”

“I’ll double our efforts immediately.”

“Excellent. I’ll expect a full report in the next few days, listing all the new contacts and what information you’ve gleaned from them. Now go, Krupp, I’ve other matters to attend to.”

Kramer didn’t even look up or salute. Hans seethed with anger, but he controlled himself and stomped to the doorway.

“And Krupp . . .”

He stopped, turning to the Lagerführer. “Ja?”

“If there is another escape, it will be your head. Understood?”

Hans nodded and left. Checking his watch, he realized he only had another half hour in his shift. He spat on the ground and headed to the exit. Forget it. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...