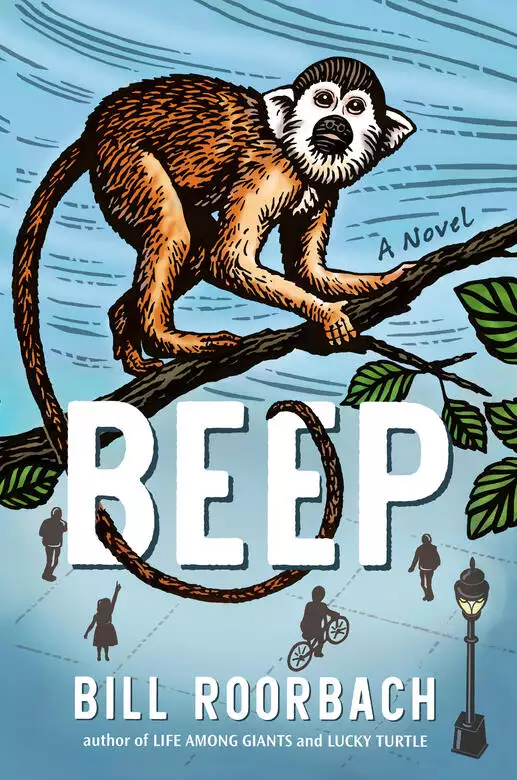

I am Beep, monkey.

I live in the world of monkeys near saltwater on the sunset side of the vast beyond. We have relations and ancestors all the way across to the sunrise side, so the old uncles say, impassable mountains in between. One of the mountains supposedly smokes, even spits fire! Legends, prophecy: somemonkey crossed over those fearsome peaks in some unexplained way to here, separating monkeydom. But, you see, a monkey one day will come along whose accidental courage will reunite us, even save the world and not only find him a mate—quest enough, we all agree. Anyway, it’s all the stuff of long discussion while mutually grooming in deep shade these hot afternoons, well fed: how could it be, that monkeys got where we are? Babies believe the legends, the old uncles believe the prophecy, but I’m a grownup now, or nearly, and on to grownup things.

I like this river we live near partly because the goers don’t come here much, except to look at the birds, our beautiful and distant cousins. I think the goers study them to perfect their own flight, which is messy, loud, and marks the sky with criss-crossing plumes. It’s the goers that make the world need saving, the old uncles say, more and more of them all the time, more and more imposing. I have noticed this even in my mere short life.

But some you-mens seem okay. Many are pleasing to look at, with fabulous black cushions of hair, or golden hair long as orchid tendrils, others with tresses red as sunsets. Once on the beach a large male caused a sensation among us—he was nearly hairy as a howler, once the peel was removed. And many you-mens are pleasant, unthreatening, a certain burbling of spirit. Some you-mens even call forth food from the land: these we call growers and consider cousins, if cautiously. But many again, the goers, we call them, are pure terror: loud, careless, unaware of the lives their sudden movements end. My old cousin Pooop got his name for his aim as the worst of them walked under us oblivious. But Pooop is dead. He climbed in their terrible black vines, lightning vines, we call them, lightning that burned that monkey so badly he smoked on the goer-stone below, that hard black stuff the goers use to make their go-ways, hot as sun.

Lately I have been so restless. The aunts observe me and say so: Beep restless. My mother, called Peep, all mine these three rainy seasons, has an infant at her breast suddenly, my breast, and on her back when we travel, my back. Mother-my-own pushes me away and for a joke calls me a punk-monkey and truly, I feel like one, ready to curse all the girl cousins aiming their rumps at me, insulting! The aunts, too, mean to me, like I’m not Swee-Beep anymore but one of the old uncles who spend their time in lonesome cogitation.

So, I go to the wise one with his many rainy seasons, one for each finger and each toe, imagine how old! I speak of my restlessness, my agitation, the busy mind.

And he holds my eye a long uncomfortable time, says, “At your age I left my inland troupe and climbed through the treetops entirely alone for ten sunsets, imagine how far, imagine how big this water when first I spotted it from the Windy Tree! I, your ancient own uncle, had never tasted the salty sea! And this troupe, now my own, came the very next morning for the Windy Tree days, and there was a particular lass that smelled like afterlife and haven’t I stayed here among us since, and now around me my children and my grandchildren and my great-grandchildren and even great-great—you are one.”

“I thought so.”

“It’s time to urinate as the grown ones do, urinate upon your hands and your feet and make your mark wherever you go—you’ve seen this practice—just don’t do it here, for here is my place to mark, and your other old uncles, if I let them, and there are too many of us, and the mademoiselles too few, all of them claimed double and triple and some more than that. We uncles await any new females, and we know they will come. They will come from the other old troupes from far inland, and some may have seen the hills, or come from the river, that way, and one day one will come who has seen the smoking mountain, even the sunrise ocean, and the sprawling verticals of the goers, all right angles rising, which I call wrong angles, and she will be queen, for she will reunite the ancient troupes.”

“Oh, uncle, those are myths, and we have no queen.”

“Myths, eh? You’ve seen the you-men enclaves, all the boxes!”

“Enclaves?”

“Their dwellings, their gatherments!”

“Ah, you mean the billages?”

“Yes, the billages. They have further separated monkeydom! Even I have seen places where the you-mens are so numerous and their dwellings so packed together that no trees can grow, or none of consequence, and no monkey can cross. You’ve seen them kill the trees. You saw it at the turn of the water.” He didn’t point but only tilted his head, aimed his gaze that way.

I said, “They made the ground hard.”

“And so hot.”

“I’ve seen hills,” I said.

“I remember. You were with us when the fruit wouldn’t come and we ventured. And that’s the way I would go if I were young again, back into the hills, as far as your arms and legs and the forest can take you, find one of the inland troupes, find one of the inland ladies tired of inland uncles and piss your way in, new troupe. And then perhaps your babies will continue toward the sunrise when it’s their turn, and then their babies, and then many through generations, always toward morning, and finally our clan will once again unite. Because when we do, the great universe will change, you’ll see. A queen, you’ll see.”

Such grand language. Meant to inspire. But I knew what my old wise great-great-grandfather was up to—he was trying to get rid of me as he would any young male coming of age.

“But when,” I said. “When do I go.”

“Today is always the right day.”

Wisdom.

So back to my mother to say farewell, but she just scolded me—baby sleeping, the very breast upon which I once. And to my aunts, who were all up high in today’s tree because of a flush of tasty pinkish bugs, and who turned their backs to me. And to my cousins, fewer today than yesterday, one-by-one gone out into the great forest and whatever lay beyond, which was more forest, from what I’d seen, or denser you-men gatherments, and after that nothing but impassable mountains, if you believed the legends, mountains full of the cries of all the scary things. Animals we didn’t know. Birds that ate monkeys, Pooop said—and this a monkey believed, because one of our own old uncles had been carried off just a handful of seasons before, biting and kicking all the way, died when he was dropped, torn apart and eaten where he lay, savage beak. From high in the sky he’d cried out—they’d all heard it, the monkeys in that generation, many still with us—“I see the smoking mountain!”

Now the troupe intones that very thing when somemonkey is extremely sick: He sees the smoking mountain.

Maybe I will be the one to see the smoking mountain but also stay alive, return to tell the tale, a girl monkey on my arm! A queen, and why not?

Popular monkey Laugh hugged me tight. She would stay—a new monkey had claimed her, and his name was Blue. He dropped down from the very height of today’s roost, a great mango tree in flower. “Do I scent urine on your hands?” he bellowed.

I demurred, but it was true, the urge had been unspeakable.

Laugh was the monkey I would most want to mate, very long tail, fine hands, neck long, eyes wide and amused, scent intoxicating, but my older sister.

“I’m going to find the smoking mountain,” I said.

And they chided me, chided me, turned their backs. I climbed high as I could, high as the highest branch that could hold me, stood tall upon it as it swayed, ocean that way, river this way, more ocean that way. But forest toward the sunrise, promise of hills, and so that direction I proceeded, the chiding of Laugh and Blue and all the cousins and my aunts and the old uncles and even my mother fading behind me, shadow of a predator bird to chase me back in under the canopy and back safe into monkey world.

I ran hand-and-foot down the longest branches and onward to branches interlaced, leaping any gaps, eye out for snakes, for cats on the ground, for bullet ants and scorpions, for poison frogs, for you-mens (especially goers!), swung arm-to-arm and flew across the gaps, brachiating it’s called, tail for balance, dropping, climbing, hands quick and fingers quicker for good things to eat: there’s a kind of grasshopper I like, and always termites, and here and there a blue lizard, which are slow and best flavor. And in the pockets of branches sips of water, nothing wanting but rest.

And so I kept the afternoon sun on my back, traveled high up in the canopy as the boldest monkeys do, leapt and swung and dove and climbed and made my way toward the sunrise. “May it ever recede!” was one travel prayer of the uncles, not one I was saying. Five trees, five more, the ignoble constructions of the goers beneath me now, this box and that, silly things impossible to understand, their treeless expanses, that hot black rock, the machines going and going, coming and coming, or resting by a dwelling, often in pairs. The canids of the goers barked, co-opted into whatever life this was, silly overweight wolves.

Five more trees again, and then five and five and five and five till nothing in the world smelled the same, and there were no more you-men dwellings, just a hot black go-way, their machines awake and roaring, grunting, hissing, farting. I’d been this far as a small. So I knew there would be a crossing that way—a monkey never forgets the way—and five more trees and five and five and five and there it was, the bluevine, we called it, but we knew it was not a vine or branch but the work of a you-men, one of the rare ones who meant to help us, to keep us off their lightning vines, a grower, likely, who’d kindly tight-braided several blue strands of some non-monkey material to make one thick blue vine, pulled taut in some way across the go-way from this grand tree to that one, thus spanning the impossible gap where the branches of friendly leafies could no longer reach one another, and so very thoughtfully creating a monkey crossing.

I availed myself gratefully, crossed the bluevine over the danger-way and back into forest, sense of a new district. In a great wrestling-fig that had overtopped its host tree I paused a long time, finally got up the nerve to climb. So high, that one, and the ever-present danger of birds, snakes, howlers. I, Beep, saw into the next valley. And then past it, though a gap unimaginably far away, a kind of vision: the hills that the old ones said came before mountains. The great fig was the furthest place I’d ever been, the furthest I could go and still know how to get back to my troupe. I could still hear the chiding of my sisters and cousins, my mother cross and rejecting, the useless gossip of the old uncles, the insults of the new males, nattering fops and dandies arriving every day.

Well, goodbye to all that.

I lingered in the fig, watched the good world a long time, those hills so promising but so far away, a kind of haze that made it all seem to fade and fade again, the greens going lighter, the blue of the sky lighter, too, till it was all one thing: destiny.

If I would be a true monkey, it was time. I took deep breaths. I greeted the hills, turning my eyes to each. I chided all the things behind me. I honored all the things ahead. I pissed carefully on each foot, then each hand, patted my fur with it, sharp smell and wild, me and we, and continued on: all the territory forward was mine.

Hungry Monkey. Each season had its foods and the troupe knew where to go to find them in abundance, or where to go and what to do if abundance failed. But the troupe knowing and I, Beep, knowing were two different things. I found that I’d confused troupe and Beep. I was, though, something even on my own, and real enough, if diminished. But here were some leaves we monkeys have always liked the taste of. And here a hurry of ants, ugh, that formic flavor, but eat. Not so much fruit, not as yet. I heard a toucan and called to her: “Toucan help this monkey.”

She said, “Nope, nope,” but then there she was, that bill like a big crab claw, and colorful.

“What’s to eat,” I said.

And she looked me over, said, “Some fine termites that way. Caught a lizard. No fruit if that’s your pleasure.” Her bill clattered: “Nope, none. Nope, nope, nope, nope, nope, nope, nope.”

Lizards aplenty, but not the good blue ones, just the big greenies, too squirmy for me, if I could even catch one. Termites though. I thanked the bird, and she clattered her bill. And had not lied. The termite mound was enormous, like a pillar of stone, unassailable, but the termite traffic was heavy and I just took a seat near one of their routes and plucked and ate them as they came and went, sharp little sweet things, oblivious of one another, so it seemed, crunchy.

“Fuck!” they’d cry when I bit them, an emotion that rippled through the entire colony. And then scarce.

I carried on traveling for an orange fistful of sunsets, slept in the protection of trees from kingdoms I knew well, the inner canopy comforting, the soft song of tree mind. In the day I got some rest, perhaps not enough, here and there a pause in a sunny break (but watch for falcons, Beep—none of the old uncles to stand sentry and sound the alarm, and this monkey jumpy—but it was only some shiny you-men roarbird the once, a large leaf falling the next), no sound or sign of monkeys like me—just the stubid howlers making their show, far away, and here and there the shit of the mean ones, which we called punks and the you-mens called spy-dirt monkeys, so the rumor went, why? Their eyes were not cast toward the ground, and they weren’t we: we were the monkeys.

Leaping a gap to a proper vine I spotted a squadron of peccaries in a wallow far below. I climbed down closer and watched them. Eventually they took notice of me, and we shouted insults back and forth (they are very funny, these fellows, and viewed from above flat as mango pits), traveled over them through my branches an afternoon, slow going and calm, laughing at their jokes, resting when they did, and surely enough they arrived at a place with sour plantains, short, thick ones like a grower’s fingers. They’d shown me the way so I helped them, knocked bunches down from the trees, saving out the ripest for me, and gobbled the bitter things as the tayassuid did. In the heat of the midday then, well stuffed, I slept on a thick branch ignoring their shouts for more. Of course I’m a lazy monkey! And you are pigs! (Peccaries hate to be called pigs!) You call those insults? Try harder! They thought I’d throw down more if they managed to anger me. And truly, once I woke, it was fun to bean a couple of them with the hardest and most unripe fruits. They’d jump and shriek and all the others would laugh. Some say they’re smart as monkeys, nope. We spent the whole afternoon unto evening at it, and then we all of us slept, each at our level: mud for them, mid-canopy me. In the morning I fed them a little more, and beaned a couple of the loud ones, shat on a snoozer’s head—don’t sleep late in monkey world!—ate a few more plantains myself, dropped as many bunches as I could to the forest floor for the peccaries, and then, well rested and well fed, also much amused, carried on, their comical shouts and laughter and fellowship behind me.

The landscape was climbing now. Ah, terrain! So, I’d made it to the hills! Nomonkey had ever been so far, I thought, only the Ancestor. I listened for our voices, but none, only the sobering cry of a forest eagle and somewhere a terrible, thundering bellow—one of the goers, no doubt, the constant cracks and pops and clangs and snarls and explosions of their handiwork.

Our trees, the mother trees of monkey life, climbed a hillside, and I climbed with them, flinging myself across the gaps, catching swinging branches as the wind rose, finally again to a crest and then the highest tree, and another view—a grower billage, but with many goers clattering their way through, so much commotion. But the trees inter-groped and without climbing too high (and thus into the open), I kept moving in the direction of sunrise, afternoon sun on my back that is, amused with all that went on below. Until I came to a place where the goers kept their rolling machines, just a vast black wasteland, as if fire had come and turned everything to rock. And the trees—few and far apart, mostly palms, which do monkeys little good, especially traveling monkeys, especially this one alone.

And hungry again.

I reversed course, found thicker forest, unpleasant wafts and whiffs of you-men, large numbers of their dwellings, those boxes. Curious, I examined more than one, no single color predominant, surrounded by unknown shrubbens all isolated and alone, a sorrowful keening. And lots of the black rock, which seemed bedding for the rolling machines. And crossed a brook, found a drink in a crook, came to a beautiful wrestling-fig tree, rested a while. Down below, yet another dwelling of a goer family, fake pond, again the forced confinement of plants, it seemed, poor shrubbens.

Suddenly I noticed a pretty you-men tween sitting in a contraption eating something off a piece of tree chopped flat and set on stilts. I sniffed voluptuously: pineapple! One of the main reasons for the monkey fondness of growers. The lean tween ate like a monkey, hand to mouth very fast, and if a piece fell on the ground retrieved it, stuffed her mouth.

There’d be none left!

A scare tactic was in order. I jumped from my hiding branch and right onto the wood plane in front of her. It shook on its stilts. But instead of shrieking and knocking over the contraption and running away on rubber feet leaving the pineapple for me, she only laughed.

“Mr. Nilsson,” she said clearly.

One thing everymonkey knows is that the goers and growers aren’t too bright, and can make no sense of us. I pointed to my mouth: sign was the best way.

“Hungry?” she said.

Litt. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved