- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Ethan Wate used to think of Gatlin, the small Southern town he had always called home, as a place where nothing ever changed. Then he met mysterious newcomer Lena Duchannes, who revealed a secret world that had been hidden in plain sight all along. A Gatlin that harbored ancient secrets beneath its moss-covered oaks and cracked sidewalks. A Gatlin where a curse has marked Lena's family of powerful Supernaturals for generations. A Gatlin where impossible, magical, life-altering events happen.

Sometimes life-ending.

Together they can face anything Gatlin throws at them, but after suffering a tragic loss, Lena starts to pull away, keeping secrets that test their relationship. And now that Ethan's eyes have been opened to the darker side of Gatlin, there's no going back. Haunted by strange visions only he can see, Ethan is pulled deeper into his town's tangled history and finds himself caught up in the dangerous network of underground passageways endlessly crisscrossing the South, where nothing is as it seems.

Sometimes life-ending.

Together they can face anything Gatlin throws at them, but after suffering a tragic loss, Lena starts to pull away, keeping secrets that test their relationship. And now that Ethan's eyes have been opened to the darker side of Gatlin, there's no going back. Haunted by strange visions only he can see, Ethan is pulled deeper into his town's tangled history and finds himself caught up in the dangerous network of underground passageways endlessly crisscrossing the South, where nothing is as it seems.

Release date: October 12, 2010

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

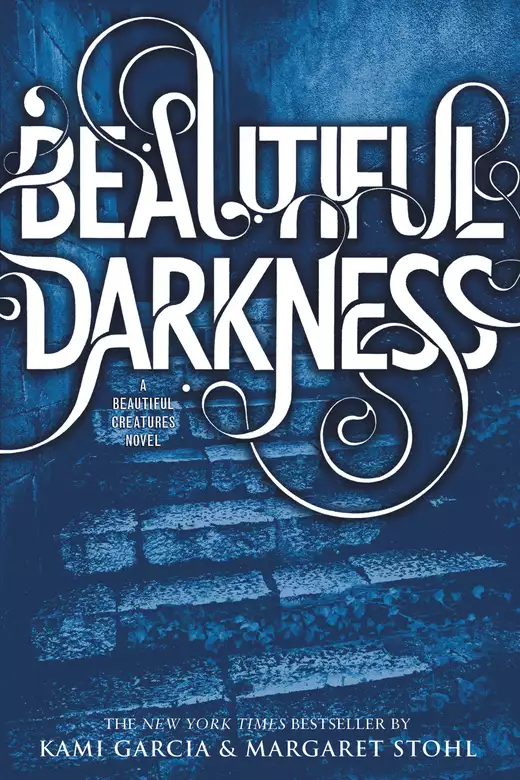

Beautiful Darkness

Kami Garcia

I used to think our town, buried in the South Carolina backwoods, stuck in the muddy bottom of the Santee River valley, was

the middle of nowhere. A place where nothing ever happened and nothing would ever change. Just like yesterday, the unblinking

sun would rise and set over the town of Gatlin without bothering to kick up so much as a breeze. Tomorrow my neighbors would

be rocking on their porches, heat and gossip and familiarity melting like ice cubes into their sweet tea, as they had for

more than a hundred years. Around here, our traditions were so traditional it was hard to put a finger on them. They were

woven into everything we did or, more often, didn’t do. You could be born or married or buried, and the Methodists kept right

on singing.

Sundays were for church, Mondays for doing the marketing at the Stop & Shop, the only grocery store in town. The rest of the week involved a whole lot of nothing and a little more pie, if you were lucky enough to live with someone like my family’s

housekeeper, Amma, who won the bake-off at the county fair every year. Old four-fingered Miss Monroe still taught cotillion,

one empty finger of her white-gloved hand flapping as she sashayed down the dance floor with the debutantes. Maybelline Sutter

was still cutting hair at the Snip ’n’ Curl, though she had lost most of her eyesight around the same time she turned seventy,

and now she forgot to put the guard down on the clippers half the time, shearing a skunk stripe up the back of your head.

Carlton Eaton never failed, rain or shine, to open your mail before he delivered it. If the news was bad, he would break it

to you himself. Better to hear it from one of your own.

This town owned us, that was the good and the bad of it. It knew every inch of us, every sin, every secret, every scab. Which

was why most people never bothered to leave, and why the ones who did never came back. Before I met Lena that would have been

me, five minutes after I graduated from Jackson High. Gone.

Then I fell in love with a Caster girl.

She showed me there was another world within the cracks of our uneven sidewalks. One that had been there all along, hidden

in plain sight. Lena’s Gatlin was a place where things happened—impossible, supernatural, life-altering things.

Sometimes life-ending.

While regular folks were busy cutting back their rosebushes or picking past worm-eaten peaches at the roadside stand, Light

and Dark Casters with unique and powerful gifts were locked in an eternal struggle—a supernatural civil war without any

hope of a white flag waving. Lena’s Gatlin was home to Demons and danger and a curse that had marked her family for more than a hundred years. And the closer I got to Lena, the

closer her Gatlin came to mine.

A few months ago, I believed nothing would ever change in this town. Now I knew better, and I only wished it was true.

Because the second I fell in love with a Caster girl, no one I loved was safe. Lena thought she was the only one cursed, but

she was wrong.

It was our curse now.

The rain dripping off the brim of Amma’s best black hat. Lena’s bare knees hitting the thick mud in front of the grave. The

pinpricks on the back of my neck that came from standing too close to so many of Macon’s kind. Incubuses—Demons who fed

off the memories and dreams of Mortals, like me, as we slept. The sound they made, unlike anything else in the universe, when

they ripped open the last bit of dark sky and disappeared just before dawn. As if they were a pack of black crows, taking

off from a power line in perfect unison.

That was Macon’s funeral.

I could remember the details as if it had happened yesterday, even though it was hard to believe some of it had happened at

all. Funerals were tricky like that. And life, I guess. The important parts you blocked out altogether, but the random, slanted

moments haunted you, replaying over and over in your mind.

What I could remember: Amma waking me up in the dark to get to His Garden of Perpetual Peace before dawn. Lena frozen and

shattered, wanting to freeze and shatter everything around her. Darkness in the sky and in half the people standing around

the grave, the ones who weren’t people at all.

But behind all that, there was something I couldn’t remember. It was there, lingering in the back of my mind. I had been trying

to think of it since Lena’s birthday, her Sixteenth Moon, the night Macon died.

The only thing I knew was that it was something I needed to remember.

The morning of the funeral it was pitch-black outside, but patches of moonlight were shining through the clouds into my open

window. My room was freezing, and I didn’t care. I had left my window open the last two nights since Macon died, like he might

just show up in my room and sit down in my swivel chair and stay awhile.

I remembered the night I saw him standing by my window, in the dark. That’s when I found out what he was. Not a vampire or

some mythological creature from a book, as I had suspected, but a real Demon. One who could have chosen to feed on blood,

but chose my dreams instead.

Macon Melchizedek Ravenwood. To the folks around here, he was Old Man Ravenwood, the town recluse. He was also Lena’s uncle,

and the only father she had ever known.

I was getting dressed in the dark when I felt the warm pull from inside that meant Lena was there.

L?

Lena spoke up from the depths of my mind, as close as anyone could be and about as far away. Kelting, our unspoken form of

communication. The whispering language Casters like her had shared long before my bedroom had been declared south of the Mason-Dixon

Line. It was the secret language of intimacy and necessity, born in a time when being different could get you burned at the

stake. It was a language we shouldn’t have been able to share, because I was a Mortal. But for some inexplicable reason we

could, and it was the language we used to speak the unspoken and the unspeakable.

I can’t do this. I’m not going.

I gave up on my tie and sat back down on my bed, the ancient mattress springs crying out beneath me.

You have to go. You won’t forgive yourself if you don’t.

For a second, she didn’t respond.

You don’t know how it feels.

I do.

I remembered when I was the one sitting on my bed afraid to get up, afraid to put on my suit and join the prayer circle and

sing Abide With Me and ride in the grim parade of headlights through town to the cemetery to bury my mother. I was afraid it would make it real.

I couldn’t stand to think about it, but I opened my mind and showed Lena.…

You can’t go, but you don’t have a choice, because Amma puts her hand on your arm and leads you into the car, into the pew,

into the pity parade. Even though it hurts to move, like your whole body aches from some kind of fever. Your eyes stop on

the mumbling faces in front of you, but you can’t actually hear what anyone is saying. Not over the screaming in your head.

So you let them put their hand on your arm, you get in the car, and it happens. Because you can make it through this if someone says you can.

I put my head in my hands.

Ethan—

I’m saying you can, L.

I shoved my fists into my eyes, and they were wet. I flipped on my light and stared at the bare bulb, refusing to blink until

I seared away the tears.

Ethan, I’m scared.

I’m right here. I’m not going anywhere.

There weren’t any more words as I went back to fumbling with my tie, but I could feel Lena there, as if she was sitting in

the corner of my room. The house seemed empty with my father gone, and I heard Amma in the hall. A second later, she was standing

quietly in the doorway clutching her good purse. Her dark eyes searched mine, and her tiny frame seemed tall, though she didn’t

even reach my shoulder. She was the grandmother I never had, and the only mother I had left now.

I stared at the empty chair next to my window, where she had laid out my good suit a little less than a year ago, then back

into the bare lightbulb of my bedside lamp.

Amma held out her hand, and I handed her my tie. Sometimes it felt like Lena wasn’t the only one who could read my mind.

I offered Amma my arm as we made our way up the muddy hill to His Garden of Perpetual Peace. The sky was dark, and the rain

started before we reached the top of the rise. Amma was in her most respectable funeral dress, with a wide hat that shielded

most of her face from the rain, except for the bit of white lace collar escaping beneath the brim. It was fastened at the neck with her best cameo, a sign of respect. I had seen it all last

April, just as I had felt her good gloves on my arm, supporting me up this hill once before. This time I couldn’t tell which

one of us was doing the supporting.

I still wasn’t sure why Macon wanted to be buried in the Gatlin cemetery, considering the way folks in this town felt about

him. But according to Gramma, Lena’s grandmother, Macon left strict instructions specifically requesting to be buried here.

He purchased the plot himself, years ago. Lena’s family hadn’t seemed happy about it, but Gramma had put her foot down. They

were going to respect his wishes, like any good Southern family.

Lena? I’m here.

I know.

I could feel my voice calming her, as if I had wrapped my arms around her. I looked up the hill, where the awning for the

graveside service would be. It would look the same as any other Gatlin funeral, which was ironic, considering it was Macon’s.

It wasn’t yet daylight, and I could barely make out a few shapes in the distance. They were all crooked, all different. The

ancient, uneven rows of tiny headstones standing at the graves of children, the overgrown family crypts, the crumbling white

obelisks honoring fallen Confederate soldiers, marked with small brass crosses. Even General Jubal A. Early, whose statue

watched over the General’s Green in the center of town, was buried here. We made our way around the family plot of a few lesser-known

Moultries, which had been there for so long the smooth magnolia trunk at the edge of the plot had grown into the side of the

tallest stone marker, making them indistinguishable.

And sacred. They were all sacred, which meant we had reached the oldest part of the graveyard. I knew from my mother, the

first word carved into any old headstone in Gatlin was Sacred. But as we got closer and my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I knew where the muddy gravel path was leading. I remembered

where it passed the stone memorial bench at the grassy slope, dotted with magnolias. I remembered my father sitting on that

bench, unable to speak or move.

My feet wouldn’t go any farther, because they had figured out the same thing I had. Macon’s Garden of Perpetual Peace was

only a magnolia away from my mother’s.

The twisting roads run straight between us.

It was a sappy line from an even sappier poem I had written Lena for Valentine’s Day. But here in the graveyard, it was true.

Who would have thought our parents, or the closest thing Lena had to one, would be neighbors in the grave?

Amma took my hand, leading me to Macon’s massive plot. “Steady now.”

We stepped inside the waist-high black railing around his gravesite, which in Gatlin was reserved for the perimeters of only

the best plots, like a white picket fence for the dead. Sometimes it actually was a white picket fence. This one was wrought

iron, the crooked door shoved open into the overgrown grass. Macon’s plot seemed to carry with it an atmosphere of its own,

like Macon himself.

Inside the railing stood Lena’s family: Gramma, Aunt Del, Uncle Barclay, Reece, Ryan, and Macon’s mother, Arelia, under the

black canopy on one side of the carved black casket. On the other side, a group of men and a woman in a long black coat kept

their distance from both the casket and the canopy, standing shoulder to shoulder in the rain. They were all bone-dry. It was like a church wedding split by an aisle down the middle,

where the relatives of the bride line up opposite the relatives of the groom like two warring clans. There was an old man

at one end of the casket, standing next to Lena. Amma and I stood at the other end, just inside the canopy.

Amma’s grip on my arm tightened, and she pulled the gold charm she always wore out from underneath her blouse and rubbed it

between her fingers. Amma was more than superstitious. She was a Seer, from generations of women who read tarot cards and

communed with spirits, and Amma had a charm or a doll for everything. This one was for protection. I stared at the Incubuses

in front of us, the rain running off their shoulders without leaving a trace. I hoped they were the kind that only fed on

dreams.

I tried to look away, but it wasn’t easy. There was something about an Incubus that drew you in like a spider’s web, like

any good predator. In the dark, you couldn’t see their black eyes, and they almost looked like a bunch of regular guys. A

few of them were dressed the way Macon always had, dark suits and expensive-looking overcoats. One or two looked more like

construction workers on their way to get a beer after work, in jeans and work boots, their hands shoved in the pockets of

their jackets. The woman was probably a Succubus. I had read about them, mostly in comics, and I thought they were just old

wives’ tales, like werewolves. But I knew I was wrong because she was standing in the rain, dry as the rest of them.

The Incubuses were a sharp contrast to Lena’s family, cloaked in iridescent black fabric that caught what little light there was and refracted it, as if they were the source themselves. I had never seen them like this before. It was a strange

sight, especially considering the strict dress code for women at Southern funerals.

In the center of it all was Lena. The way she looked was the opposite of magical. She stood in front of the casket with her

fingers quietly resting upon it, as if Macon was somehow holding her hand. She was dressed in the same shimmering material

as the rest of her family, but it hung on her like a shadow. Her black hair was twisted into a tight knot, not a trademark

curl in sight. She looked broken and out of place, like she was standing on the wrong side of the aisle.

Like she belonged with Macon’s other family, standing in the rain.

Lena?

She lifted her head, and her eyes met mine. Since her birthday, when one of her eyes had turned a shade of gold while the

other remained deep green, the colors had combined to create a shade unlike anything I’d ever seen. Almost hazel at times,

and unnaturally golden at others. Now they looked more hazel, dull and pained. I couldn’t stand it. I wanted to pick her up

and carry her away.

I can get the Volvo, and we can drive down the coast all the way to Savannah. We can hide out at my Aunt Caroline’s.

I took another step closer to her. Her family was crowded around the casket, and I couldn’t get to Lena without walking past

the line of Incubuses, but I didn’t care.

Ethan, stop! It’s not safe—

A tall Incubus with a scar running down the length of his face, like the mark of a savage animal attack, turned his head to look at me. The air seemed to ripple through the space between us, like I had chucked a stone into a lake. It hit me, knocking

the wind out of my lungs as if I’d been punched, but I couldn’t react because I felt paralyzed—my limbs numb and useless.

Ethan!

Amma’s eyes narrowed, but before she could take a step the Succubus put her hand on Scarface’s shoulder and squeezed it, almost

imperceptibly. Instantly, I was released from his hold, and the blood rushed back into my limbs. Amma gave her a grateful

nod, but the woman with the long hair and the longer coat ignored her, disappearing back into line with the rest of them.

The Incubus with the brutal scar turned and winked at me. I got the message, even without the words. See you in your dreams.

I was still holding my breath when a white-haired gentleman, in an old-fashioned suit and string tie, stepped up to the coffin.

His eyes were a dark contrast to his hair, which made him seem like some creepy character from an old black and white movie.

“The Gravecaster,” Amma whispered. He looked more like the gravedigger.

He touched the smooth black wood, and a carved crest on the top of the coffin began to glow with a golden light. It looked

like some old coat of arms, the kind of thing you saw at a museum or in a castle. I saw a tree with great spreading boughs,

and a bird. Beneath it there was a carved sun, and a crescent moon.

“Macon Ravenwood of the House of Ravenwood, of Raven and Oak, Air and Earth. Darkness and Light.” He took his hand from the coffin, and the light followed, leaving the casket dark again.

“Is that Macon?” I whispered to Amma.

“The light’s symbolic. There’s nothin’ in that box. Wasn’t anythin’ left to bury. That’s the way with Macon’s kind—ashes

to ashes and dust to dust, like us. Just a whole lot quicker.”

The Gravecaster’s voice rose up again. “Who consecrates this soul into the Otherworld?”

Lena’s family stepped forward. “We do,” they said in unison, everyone except Lena. She stood there staring down at the dirt.

“As do we.” The Incubuses moved closer to the casket.

“Then let him be Cast to the world beyond. Redi in pace, ad Ignem Atrum ex quo venisti.” The Gravecaster held the light high over his head, and it flared brighter. “Go in peace, back to the Dark Fire from where

you came.” He threw the light into the air, and sparks showered down onto the coffin, searing into the wood where they fell.

As if on cue, Lena’s family and the Incubuses threw their hands into the air, releasing tiny silver objects not much bigger

than quarters, which rained down onto Macon’s coffin amidst the gold flames. The sky was starting to change color, from the

black of night to the blue before the sunrise. I strained to see what the objects were, but it was too dark.

“His dictis, solutus est. With these words, he is free.”

An almost blinding white light emanated from the casket. I could barely see the Gravecaster a few feet in front of me, as

if his voice was transporting us and we were no longer standing over a gravesite in Gatlin.

Uncle Macon! No!

The light flashed, like lightning striking, and died out. We were all back in the circle, looking at a mound of dirt and flowers. The burial was over. The coffin was gone. Aunt Del put

her arms protectively around Reece and Ryan.

Macon was gone.

Lena fell forward onto her knees in the muddy grass.

The gate around Macon’s plot slammed shut behind her, without so much as a finger touching it. This wasn’t over for her. No

one was going anywhere.

Lena?

The rain started to pick up almost immediately, the weather still tethered to her powers as a Natural, the ultimate elemental

in the Caster world. She pulled herself to her feet.

Lena! This isn’t going to change anything!

The air filled with hundreds of cheap white carnations and plastic flowers and palmetto fronds and flags from every grave

visited in the last month, all flying loose in the air, tumbling airborne down the hill. Fifty years from now, folks in town

would still be talking about the day the wind almost blew down every magnolia in His Garden of Perpetual Peace. The gale came

on so fierce and fast, it was a slap in the face to everyone there, a hit so hard you had to stagger to stay on your feet.

Only Lena stood straight and tall, holding fast to the stone marker next to her. Her hair had unraveled from its awkward knot

and whipped in the air around her. She was no longer all darkness and shadow. She was the opposite—the one bright spot in

the storm, as if the yellowish-gold lightning splitting the sky above us was emanating from her body. Boo Radley, Macon’s

dog, whimpered and flattened his ears at Lena’s feet.

He wouldn’t want this, L.

Lena put her face in her hands, and a sudden gust blew the canopy out from where it was staked in the wet earth, sending it tumbling backward down the hill.

Gramma stepped in front of Lena, closed her eyes, and touched a single finger to her granddaughter’s cheek. The moment she

touched Lena, everything stopped, and I knew Gramma had used her abilities as an Empath to absorb Lena’s powers temporarily.

But she couldn’t absorb Lena’s anger. None of us were strong enough to do that.

The wind died down, and the rain slowed to a drizzle. Gramma pulled her hand away from Lena and opened her eyes.

The Succubus, looking unusually disheveled, stared up at the sky. “It’s almost sunrise.” The sun was beginning to burn its

way up through the clouds and over the horizon, scattering odd splinters of light and life across the uneven rows of headstones.

Nothing else had to be said. The Incubuses started to dematerialize, the sound of suction filling the air. Ripping was how

I thought of it, the way they pulled open the sky and disappeared.

I started to walk toward Lena, but Amma yanked my arm. “What? They’re gone.”

“Not all a them. Look—”

She was right. At the edge of the plot, there was only one Incubus remaining, leaning against a weathered headstone adorned

with a weeping angel. He looked older than I was, maybe nineteen, with short, black hair and the same pale skin as the rest

of his kind. But unlike the other Incubuses, he hadn’t disappeared before the dawn. As I watched him, he moved out from under

the shadow of the oak directly into the bright morning light, with his eyes closed and his face tilted toward the sun, as

if it was only shining for him.

Amma was wrong. He couldn’t be one of them. He stood there basking in the sunlight, an impossibility for an Incubus.

What was he? And what was he doing here?

He moved closer and caught my eye, as if he could feel me watching him. That’s when I saw his eyes. They weren’t the black

eyes of an Incubus.

They were Caster green.

He stopped in front of Lena, jamming his hands in his pockets, tipping his head slightly. Not a bow, but an awkward show of

deference, which somehow seemed more honest. He had crossed the invisible aisle, and in a moment of real Southern gentility,

he could have been the son of Macon Ravenwood himself. Which made me hate him.

“I’m sorry for your loss.”

He opened her hand and placed a small silver object in it, like the ones everyone had thrown onto Macon’s casket. Her fingers

closed around it. Before I could move a muscle, the unmistakable ripping sound tore through the air, and he was gone.

Ethan?

I saw her legs begin to buckle under the weight of the morning—the loss, the storm, even the final rip in the sky. By the

time I made it to her side and slid my arm under her, she was gone, too. I carried her down the sloping hill, away from Macon

and the cemetery.

She slept curled in my bed, on and off, for a night and a day. She had a few stray twigs matted in her hair, and her face

was still flecked with mud, but she wouldn’t go home to Ravenwood, and no one asked her to. I had given her my oldest, softest

sweatshirt and wrapped her in our thickest patchwork quilt, but she never stopped shivering, even in her sleep. Boo lay at

her feet, and Amma appeared in the doorway every now and then. I sat in the chair by the window, the one I never sat in, and stared

out at the sky. I couldn’t open it, because a storm was still brewing.

As Lena was sleeping, her fingers uncurled. In them was a tiny bird made of silver, a sparrow. A gift from the stranger at

Macon’s funeral. I tried to take it from her hand just as her fingers tightened around it.

Two months later, and I still couldn’t look at a bird without hearing the sound of the sky ripping open.

Four eggs, four strips of bacon, a basket of scratch biscuits (which by Amma’s standard meant a spoon had never touched the

batter), three kinds of freezer jam, and a slab of butter drizzled with honey. And from the smell of it, across the counter

buttermilk batter was separating into squares, turning crisp in the old waffle iron. For the last two months, Amma had been

cooking night and day. The counter was piled high with Pyrex dishes—cheese grits, green bean casserole, fried chicken, and

of course, Bing cherry salad, which was really a fancy name for a Jell-O mold with cherries, pineapple, and Coca-Cola in it.

Past that, I could make out a coconut cake, orange rolls, and what looked like bourbon bread pudding, but I knew there was

more. Since Macon died and my dad left, Amma kept cooking and baking and stacking, as if she could cook her sadness away.

We both knew she couldn’t.

Amma hadn’t gone this dark since my mom died. She’d known Macon Ravenwood a lifetime longer than I had, even longer than Lena.

No matter how unlikely or unpredictable their relationship was, it had meant something to both of them. They were friends,

though I wasn’t sure either of them would’ve admitted it. But I knew the truth. Amma was wearing it all over her face and

stacking it all over our kitchen.

“Got a call from Dr. Summers.” My dad’s psychiatrist. Amma didn’t look up from the waffle iron, and I didn’t point out that

you didn’t actually need to stare at a waffle iron for it to cook the waffles.

“What’d he say?” I studied her back from my seat at the old oak table, her apron strings tied in the middle. I remembered

how many times I had tried to sneak up on her and untie those strings. Amma was so short they hung down almost as long as

the apron itself, and I thought about that for as long as I could. Anything was better than thinking about my father.

“He thinks your daddy’s about ready to come home.”

I held up my empty glass and stared through it, where things looked as distorted as they really were. My dad had been at Blue

Horizons, in Columbia, for two months. After Amma found out about the nonexistent book he was pretending to write all year,

and the “incident,” which is how she referred to my dad nearly jumping off a balcony, she called my Aunt Caroline. My aunt

drove him to Blue Horizons that same day—she called it a spa. The kind of spa you sent your crazy relatives to if they needed

what folks in Gatlin referred to as “individual attention,” or what everyone outside of the South would call therapy.

“Great.”

Great. I couldn’t see my dad coming home to Gatlin, walking around town in his duck pajamas. There was enough crazy around here

already between Amma and me, wedged in between the cream-of-grief casseroles I’d be dropping off at First Methodist around

dinnertime, as I did almost every night. I wasn’t an expert on feelings, but Amma’s were all stirred up in cake batter, and

she wasn’t about to share them. She’d rather give away the cake.

I tried to talk to her about it once, the day after the funeral, but she had shut down the conversation before it even started.

“Done is done. Gone is gone. Where Macon Ravenwood is now, not likely we’ll ever see him again, not in this world or the Other.”

She sounded like she’d made her peace with it, but here I was, two months later, still delivering cakes and casseroles. She

had lost the two men in her life the same night—my father and Macon. My dad wasn’t dead, but our kitchen didn’t make those

kinds of distinctions. Like Amma said, gone was gone.

“I’m makin’ waffles. Hope you’re hungry.”

That was probably all I’d hear from her this morning. I picked up the carton of chocolate milk next to my glass and poured

it full out of habit. Amma used to complain when I drank chocolate milk at breakfast. Now she would have cut me up a whole

Tunnel of Fudge cake w

the middle of nowhere. A place where nothing ever happened and nothing would ever change. Just like yesterday, the unblinking

sun would rise and set over the town of Gatlin without bothering to kick up so much as a breeze. Tomorrow my neighbors would

be rocking on their porches, heat and gossip and familiarity melting like ice cubes into their sweet tea, as they had for

more than a hundred years. Around here, our traditions were so traditional it was hard to put a finger on them. They were

woven into everything we did or, more often, didn’t do. You could be born or married or buried, and the Methodists kept right

on singing.

Sundays were for church, Mondays for doing the marketing at the Stop & Shop, the only grocery store in town. The rest of the week involved a whole lot of nothing and a little more pie, if you were lucky enough to live with someone like my family’s

housekeeper, Amma, who won the bake-off at the county fair every year. Old four-fingered Miss Monroe still taught cotillion,

one empty finger of her white-gloved hand flapping as she sashayed down the dance floor with the debutantes. Maybelline Sutter

was still cutting hair at the Snip ’n’ Curl, though she had lost most of her eyesight around the same time she turned seventy,

and now she forgot to put the guard down on the clippers half the time, shearing a skunk stripe up the back of your head.

Carlton Eaton never failed, rain or shine, to open your mail before he delivered it. If the news was bad, he would break it

to you himself. Better to hear it from one of your own.

This town owned us, that was the good and the bad of it. It knew every inch of us, every sin, every secret, every scab. Which

was why most people never bothered to leave, and why the ones who did never came back. Before I met Lena that would have been

me, five minutes after I graduated from Jackson High. Gone.

Then I fell in love with a Caster girl.

She showed me there was another world within the cracks of our uneven sidewalks. One that had been there all along, hidden

in plain sight. Lena’s Gatlin was a place where things happened—impossible, supernatural, life-altering things.

Sometimes life-ending.

While regular folks were busy cutting back their rosebushes or picking past worm-eaten peaches at the roadside stand, Light

and Dark Casters with unique and powerful gifts were locked in an eternal struggle—a supernatural civil war without any

hope of a white flag waving. Lena’s Gatlin was home to Demons and danger and a curse that had marked her family for more than a hundred years. And the closer I got to Lena, the

closer her Gatlin came to mine.

A few months ago, I believed nothing would ever change in this town. Now I knew better, and I only wished it was true.

Because the second I fell in love with a Caster girl, no one I loved was safe. Lena thought she was the only one cursed, but

she was wrong.

It was our curse now.

The rain dripping off the brim of Amma’s best black hat. Lena’s bare knees hitting the thick mud in front of the grave. The

pinpricks on the back of my neck that came from standing too close to so many of Macon’s kind. Incubuses—Demons who fed

off the memories and dreams of Mortals, like me, as we slept. The sound they made, unlike anything else in the universe, when

they ripped open the last bit of dark sky and disappeared just before dawn. As if they were a pack of black crows, taking

off from a power line in perfect unison.

That was Macon’s funeral.

I could remember the details as if it had happened yesterday, even though it was hard to believe some of it had happened at

all. Funerals were tricky like that. And life, I guess. The important parts you blocked out altogether, but the random, slanted

moments haunted you, replaying over and over in your mind.

What I could remember: Amma waking me up in the dark to get to His Garden of Perpetual Peace before dawn. Lena frozen and

shattered, wanting to freeze and shatter everything around her. Darkness in the sky and in half the people standing around

the grave, the ones who weren’t people at all.

But behind all that, there was something I couldn’t remember. It was there, lingering in the back of my mind. I had been trying

to think of it since Lena’s birthday, her Sixteenth Moon, the night Macon died.

The only thing I knew was that it was something I needed to remember.

The morning of the funeral it was pitch-black outside, but patches of moonlight were shining through the clouds into my open

window. My room was freezing, and I didn’t care. I had left my window open the last two nights since Macon died, like he might

just show up in my room and sit down in my swivel chair and stay awhile.

I remembered the night I saw him standing by my window, in the dark. That’s when I found out what he was. Not a vampire or

some mythological creature from a book, as I had suspected, but a real Demon. One who could have chosen to feed on blood,

but chose my dreams instead.

Macon Melchizedek Ravenwood. To the folks around here, he was Old Man Ravenwood, the town recluse. He was also Lena’s uncle,

and the only father she had ever known.

I was getting dressed in the dark when I felt the warm pull from inside that meant Lena was there.

L?

Lena spoke up from the depths of my mind, as close as anyone could be and about as far away. Kelting, our unspoken form of

communication. The whispering language Casters like her had shared long before my bedroom had been declared south of the Mason-Dixon

Line. It was the secret language of intimacy and necessity, born in a time when being different could get you burned at the

stake. It was a language we shouldn’t have been able to share, because I was a Mortal. But for some inexplicable reason we

could, and it was the language we used to speak the unspoken and the unspeakable.

I can’t do this. I’m not going.

I gave up on my tie and sat back down on my bed, the ancient mattress springs crying out beneath me.

You have to go. You won’t forgive yourself if you don’t.

For a second, she didn’t respond.

You don’t know how it feels.

I do.

I remembered when I was the one sitting on my bed afraid to get up, afraid to put on my suit and join the prayer circle and

sing Abide With Me and ride in the grim parade of headlights through town to the cemetery to bury my mother. I was afraid it would make it real.

I couldn’t stand to think about it, but I opened my mind and showed Lena.…

You can’t go, but you don’t have a choice, because Amma puts her hand on your arm and leads you into the car, into the pew,

into the pity parade. Even though it hurts to move, like your whole body aches from some kind of fever. Your eyes stop on

the mumbling faces in front of you, but you can’t actually hear what anyone is saying. Not over the screaming in your head.

So you let them put their hand on your arm, you get in the car, and it happens. Because you can make it through this if someone says you can.

I put my head in my hands.

Ethan—

I’m saying you can, L.

I shoved my fists into my eyes, and they were wet. I flipped on my light and stared at the bare bulb, refusing to blink until

I seared away the tears.

Ethan, I’m scared.

I’m right here. I’m not going anywhere.

There weren’t any more words as I went back to fumbling with my tie, but I could feel Lena there, as if she was sitting in

the corner of my room. The house seemed empty with my father gone, and I heard Amma in the hall. A second later, she was standing

quietly in the doorway clutching her good purse. Her dark eyes searched mine, and her tiny frame seemed tall, though she didn’t

even reach my shoulder. She was the grandmother I never had, and the only mother I had left now.

I stared at the empty chair next to my window, where she had laid out my good suit a little less than a year ago, then back

into the bare lightbulb of my bedside lamp.

Amma held out her hand, and I handed her my tie. Sometimes it felt like Lena wasn’t the only one who could read my mind.

I offered Amma my arm as we made our way up the muddy hill to His Garden of Perpetual Peace. The sky was dark, and the rain

started before we reached the top of the rise. Amma was in her most respectable funeral dress, with a wide hat that shielded

most of her face from the rain, except for the bit of white lace collar escaping beneath the brim. It was fastened at the neck with her best cameo, a sign of respect. I had seen it all last

April, just as I had felt her good gloves on my arm, supporting me up this hill once before. This time I couldn’t tell which

one of us was doing the supporting.

I still wasn’t sure why Macon wanted to be buried in the Gatlin cemetery, considering the way folks in this town felt about

him. But according to Gramma, Lena’s grandmother, Macon left strict instructions specifically requesting to be buried here.

He purchased the plot himself, years ago. Lena’s family hadn’t seemed happy about it, but Gramma had put her foot down. They

were going to respect his wishes, like any good Southern family.

Lena? I’m here.

I know.

I could feel my voice calming her, as if I had wrapped my arms around her. I looked up the hill, where the awning for the

graveside service would be. It would look the same as any other Gatlin funeral, which was ironic, considering it was Macon’s.

It wasn’t yet daylight, and I could barely make out a few shapes in the distance. They were all crooked, all different. The

ancient, uneven rows of tiny headstones standing at the graves of children, the overgrown family crypts, the crumbling white

obelisks honoring fallen Confederate soldiers, marked with small brass crosses. Even General Jubal A. Early, whose statue

watched over the General’s Green in the center of town, was buried here. We made our way around the family plot of a few lesser-known

Moultries, which had been there for so long the smooth magnolia trunk at the edge of the plot had grown into the side of the

tallest stone marker, making them indistinguishable.

And sacred. They were all sacred, which meant we had reached the oldest part of the graveyard. I knew from my mother, the

first word carved into any old headstone in Gatlin was Sacred. But as we got closer and my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I knew where the muddy gravel path was leading. I remembered

where it passed the stone memorial bench at the grassy slope, dotted with magnolias. I remembered my father sitting on that

bench, unable to speak or move.

My feet wouldn’t go any farther, because they had figured out the same thing I had. Macon’s Garden of Perpetual Peace was

only a magnolia away from my mother’s.

The twisting roads run straight between us.

It was a sappy line from an even sappier poem I had written Lena for Valentine’s Day. But here in the graveyard, it was true.

Who would have thought our parents, or the closest thing Lena had to one, would be neighbors in the grave?

Amma took my hand, leading me to Macon’s massive plot. “Steady now.”

We stepped inside the waist-high black railing around his gravesite, which in Gatlin was reserved for the perimeters of only

the best plots, like a white picket fence for the dead. Sometimes it actually was a white picket fence. This one was wrought

iron, the crooked door shoved open into the overgrown grass. Macon’s plot seemed to carry with it an atmosphere of its own,

like Macon himself.

Inside the railing stood Lena’s family: Gramma, Aunt Del, Uncle Barclay, Reece, Ryan, and Macon’s mother, Arelia, under the

black canopy on one side of the carved black casket. On the other side, a group of men and a woman in a long black coat kept

their distance from both the casket and the canopy, standing shoulder to shoulder in the rain. They were all bone-dry. It was like a church wedding split by an aisle down the middle,

where the relatives of the bride line up opposite the relatives of the groom like two warring clans. There was an old man

at one end of the casket, standing next to Lena. Amma and I stood at the other end, just inside the canopy.

Amma’s grip on my arm tightened, and she pulled the gold charm she always wore out from underneath her blouse and rubbed it

between her fingers. Amma was more than superstitious. She was a Seer, from generations of women who read tarot cards and

communed with spirits, and Amma had a charm or a doll for everything. This one was for protection. I stared at the Incubuses

in front of us, the rain running off their shoulders without leaving a trace. I hoped they were the kind that only fed on

dreams.

I tried to look away, but it wasn’t easy. There was something about an Incubus that drew you in like a spider’s web, like

any good predator. In the dark, you couldn’t see their black eyes, and they almost looked like a bunch of regular guys. A

few of them were dressed the way Macon always had, dark suits and expensive-looking overcoats. One or two looked more like

construction workers on their way to get a beer after work, in jeans and work boots, their hands shoved in the pockets of

their jackets. The woman was probably a Succubus. I had read about them, mostly in comics, and I thought they were just old

wives’ tales, like werewolves. But I knew I was wrong because she was standing in the rain, dry as the rest of them.

The Incubuses were a sharp contrast to Lena’s family, cloaked in iridescent black fabric that caught what little light there was and refracted it, as if they were the source themselves. I had never seen them like this before. It was a strange

sight, especially considering the strict dress code for women at Southern funerals.

In the center of it all was Lena. The way she looked was the opposite of magical. She stood in front of the casket with her

fingers quietly resting upon it, as if Macon was somehow holding her hand. She was dressed in the same shimmering material

as the rest of her family, but it hung on her like a shadow. Her black hair was twisted into a tight knot, not a trademark

curl in sight. She looked broken and out of place, like she was standing on the wrong side of the aisle.

Like she belonged with Macon’s other family, standing in the rain.

Lena?

She lifted her head, and her eyes met mine. Since her birthday, when one of her eyes had turned a shade of gold while the

other remained deep green, the colors had combined to create a shade unlike anything I’d ever seen. Almost hazel at times,

and unnaturally golden at others. Now they looked more hazel, dull and pained. I couldn’t stand it. I wanted to pick her up

and carry her away.

I can get the Volvo, and we can drive down the coast all the way to Savannah. We can hide out at my Aunt Caroline’s.

I took another step closer to her. Her family was crowded around the casket, and I couldn’t get to Lena without walking past

the line of Incubuses, but I didn’t care.

Ethan, stop! It’s not safe—

A tall Incubus with a scar running down the length of his face, like the mark of a savage animal attack, turned his head to look at me. The air seemed to ripple through the space between us, like I had chucked a stone into a lake. It hit me, knocking

the wind out of my lungs as if I’d been punched, but I couldn’t react because I felt paralyzed—my limbs numb and useless.

Ethan!

Amma’s eyes narrowed, but before she could take a step the Succubus put her hand on Scarface’s shoulder and squeezed it, almost

imperceptibly. Instantly, I was released from his hold, and the blood rushed back into my limbs. Amma gave her a grateful

nod, but the woman with the long hair and the longer coat ignored her, disappearing back into line with the rest of them.

The Incubus with the brutal scar turned and winked at me. I got the message, even without the words. See you in your dreams.

I was still holding my breath when a white-haired gentleman, in an old-fashioned suit and string tie, stepped up to the coffin.

His eyes were a dark contrast to his hair, which made him seem like some creepy character from an old black and white movie.

“The Gravecaster,” Amma whispered. He looked more like the gravedigger.

He touched the smooth black wood, and a carved crest on the top of the coffin began to glow with a golden light. It looked

like some old coat of arms, the kind of thing you saw at a museum or in a castle. I saw a tree with great spreading boughs,

and a bird. Beneath it there was a carved sun, and a crescent moon.

“Macon Ravenwood of the House of Ravenwood, of Raven and Oak, Air and Earth. Darkness and Light.” He took his hand from the coffin, and the light followed, leaving the casket dark again.

“Is that Macon?” I whispered to Amma.

“The light’s symbolic. There’s nothin’ in that box. Wasn’t anythin’ left to bury. That’s the way with Macon’s kind—ashes

to ashes and dust to dust, like us. Just a whole lot quicker.”

The Gravecaster’s voice rose up again. “Who consecrates this soul into the Otherworld?”

Lena’s family stepped forward. “We do,” they said in unison, everyone except Lena. She stood there staring down at the dirt.

“As do we.” The Incubuses moved closer to the casket.

“Then let him be Cast to the world beyond. Redi in pace, ad Ignem Atrum ex quo venisti.” The Gravecaster held the light high over his head, and it flared brighter. “Go in peace, back to the Dark Fire from where

you came.” He threw the light into the air, and sparks showered down onto the coffin, searing into the wood where they fell.

As if on cue, Lena’s family and the Incubuses threw their hands into the air, releasing tiny silver objects not much bigger

than quarters, which rained down onto Macon’s coffin amidst the gold flames. The sky was starting to change color, from the

black of night to the blue before the sunrise. I strained to see what the objects were, but it was too dark.

“His dictis, solutus est. With these words, he is free.”

An almost blinding white light emanated from the casket. I could barely see the Gravecaster a few feet in front of me, as

if his voice was transporting us and we were no longer standing over a gravesite in Gatlin.

Uncle Macon! No!

The light flashed, like lightning striking, and died out. We were all back in the circle, looking at a mound of dirt and flowers. The burial was over. The coffin was gone. Aunt Del put

her arms protectively around Reece and Ryan.

Macon was gone.

Lena fell forward onto her knees in the muddy grass.

The gate around Macon’s plot slammed shut behind her, without so much as a finger touching it. This wasn’t over for her. No

one was going anywhere.

Lena?

The rain started to pick up almost immediately, the weather still tethered to her powers as a Natural, the ultimate elemental

in the Caster world. She pulled herself to her feet.

Lena! This isn’t going to change anything!

The air filled with hundreds of cheap white carnations and plastic flowers and palmetto fronds and flags from every grave

visited in the last month, all flying loose in the air, tumbling airborne down the hill. Fifty years from now, folks in town

would still be talking about the day the wind almost blew down every magnolia in His Garden of Perpetual Peace. The gale came

on so fierce and fast, it was a slap in the face to everyone there, a hit so hard you had to stagger to stay on your feet.

Only Lena stood straight and tall, holding fast to the stone marker next to her. Her hair had unraveled from its awkward knot

and whipped in the air around her. She was no longer all darkness and shadow. She was the opposite—the one bright spot in

the storm, as if the yellowish-gold lightning splitting the sky above us was emanating from her body. Boo Radley, Macon’s

dog, whimpered and flattened his ears at Lena’s feet.

He wouldn’t want this, L.

Lena put her face in her hands, and a sudden gust blew the canopy out from where it was staked in the wet earth, sending it tumbling backward down the hill.

Gramma stepped in front of Lena, closed her eyes, and touched a single finger to her granddaughter’s cheek. The moment she

touched Lena, everything stopped, and I knew Gramma had used her abilities as an Empath to absorb Lena’s powers temporarily.

But she couldn’t absorb Lena’s anger. None of us were strong enough to do that.

The wind died down, and the rain slowed to a drizzle. Gramma pulled her hand away from Lena and opened her eyes.

The Succubus, looking unusually disheveled, stared up at the sky. “It’s almost sunrise.” The sun was beginning to burn its

way up through the clouds and over the horizon, scattering odd splinters of light and life across the uneven rows of headstones.

Nothing else had to be said. The Incubuses started to dematerialize, the sound of suction filling the air. Ripping was how

I thought of it, the way they pulled open the sky and disappeared.

I started to walk toward Lena, but Amma yanked my arm. “What? They’re gone.”

“Not all a them. Look—”

She was right. At the edge of the plot, there was only one Incubus remaining, leaning against a weathered headstone adorned

with a weeping angel. He looked older than I was, maybe nineteen, with short, black hair and the same pale skin as the rest

of his kind. But unlike the other Incubuses, he hadn’t disappeared before the dawn. As I watched him, he moved out from under

the shadow of the oak directly into the bright morning light, with his eyes closed and his face tilted toward the sun, as

if it was only shining for him.

Amma was wrong. He couldn’t be one of them. He stood there basking in the sunlight, an impossibility for an Incubus.

What was he? And what was he doing here?

He moved closer and caught my eye, as if he could feel me watching him. That’s when I saw his eyes. They weren’t the black

eyes of an Incubus.

They were Caster green.

He stopped in front of Lena, jamming his hands in his pockets, tipping his head slightly. Not a bow, but an awkward show of

deference, which somehow seemed more honest. He had crossed the invisible aisle, and in a moment of real Southern gentility,

he could have been the son of Macon Ravenwood himself. Which made me hate him.

“I’m sorry for your loss.”

He opened her hand and placed a small silver object in it, like the ones everyone had thrown onto Macon’s casket. Her fingers

closed around it. Before I could move a muscle, the unmistakable ripping sound tore through the air, and he was gone.

Ethan?

I saw her legs begin to buckle under the weight of the morning—the loss, the storm, even the final rip in the sky. By the

time I made it to her side and slid my arm under her, she was gone, too. I carried her down the sloping hill, away from Macon

and the cemetery.

She slept curled in my bed, on and off, for a night and a day. She had a few stray twigs matted in her hair, and her face

was still flecked with mud, but she wouldn’t go home to Ravenwood, and no one asked her to. I had given her my oldest, softest

sweatshirt and wrapped her in our thickest patchwork quilt, but she never stopped shivering, even in her sleep. Boo lay at

her feet, and Amma appeared in the doorway every now and then. I sat in the chair by the window, the one I never sat in, and stared

out at the sky. I couldn’t open it, because a storm was still brewing.

As Lena was sleeping, her fingers uncurled. In them was a tiny bird made of silver, a sparrow. A gift from the stranger at

Macon’s funeral. I tried to take it from her hand just as her fingers tightened around it.

Two months later, and I still couldn’t look at a bird without hearing the sound of the sky ripping open.

Four eggs, four strips of bacon, a basket of scratch biscuits (which by Amma’s standard meant a spoon had never touched the

batter), three kinds of freezer jam, and a slab of butter drizzled with honey. And from the smell of it, across the counter

buttermilk batter was separating into squares, turning crisp in the old waffle iron. For the last two months, Amma had been

cooking night and day. The counter was piled high with Pyrex dishes—cheese grits, green bean casserole, fried chicken, and

of course, Bing cherry salad, which was really a fancy name for a Jell-O mold with cherries, pineapple, and Coca-Cola in it.

Past that, I could make out a coconut cake, orange rolls, and what looked like bourbon bread pudding, but I knew there was

more. Since Macon died and my dad left, Amma kept cooking and baking and stacking, as if she could cook her sadness away.

We both knew she couldn’t.

Amma hadn’t gone this dark since my mom died. She’d known Macon Ravenwood a lifetime longer than I had, even longer than Lena.

No matter how unlikely or unpredictable their relationship was, it had meant something to both of them. They were friends,

though I wasn’t sure either of them would’ve admitted it. But I knew the truth. Amma was wearing it all over her face and

stacking it all over our kitchen.

“Got a call from Dr. Summers.” My dad’s psychiatrist. Amma didn’t look up from the waffle iron, and I didn’t point out that

you didn’t actually need to stare at a waffle iron for it to cook the waffles.

“What’d he say?” I studied her back from my seat at the old oak table, her apron strings tied in the middle. I remembered

how many times I had tried to sneak up on her and untie those strings. Amma was so short they hung down almost as long as

the apron itself, and I thought about that for as long as I could. Anything was better than thinking about my father.

“He thinks your daddy’s about ready to come home.”

I held up my empty glass and stared through it, where things looked as distorted as they really were. My dad had been at Blue

Horizons, in Columbia, for two months. After Amma found out about the nonexistent book he was pretending to write all year,

and the “incident,” which is how she referred to my dad nearly jumping off a balcony, she called my Aunt Caroline. My aunt

drove him to Blue Horizons that same day—she called it a spa. The kind of spa you sent your crazy relatives to if they needed

what folks in Gatlin referred to as “individual attention,” or what everyone outside of the South would call therapy.

“Great.”

Great. I couldn’t see my dad coming home to Gatlin, walking around town in his duck pajamas. There was enough crazy around here

already between Amma and me, wedged in between the cream-of-grief casseroles I’d be dropping off at First Methodist around

dinnertime, as I did almost every night. I wasn’t an expert on feelings, but Amma’s were all stirred up in cake batter, and

she wasn’t about to share them. She’d rather give away the cake.

I tried to talk to her about it once, the day after the funeral, but she had shut down the conversation before it even started.

“Done is done. Gone is gone. Where Macon Ravenwood is now, not likely we’ll ever see him again, not in this world or the Other.”

She sounded like she’d made her peace with it, but here I was, two months later, still delivering cakes and casseroles. She

had lost the two men in her life the same night—my father and Macon. My dad wasn’t dead, but our kitchen didn’t make those

kinds of distinctions. Like Amma said, gone was gone.

“I’m makin’ waffles. Hope you’re hungry.”

That was probably all I’d hear from her this morning. I picked up the carton of chocolate milk next to my glass and poured

it full out of habit. Amma used to complain when I drank chocolate milk at breakfast. Now she would have cut me up a whole

Tunnel of Fudge cake w

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved