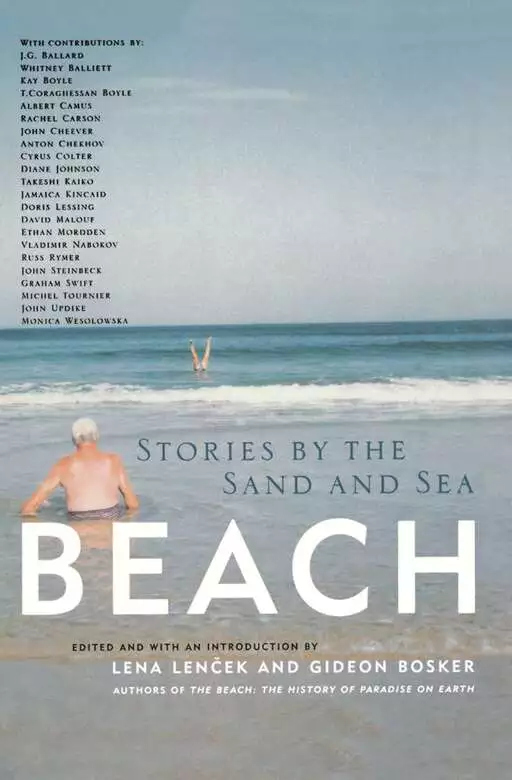

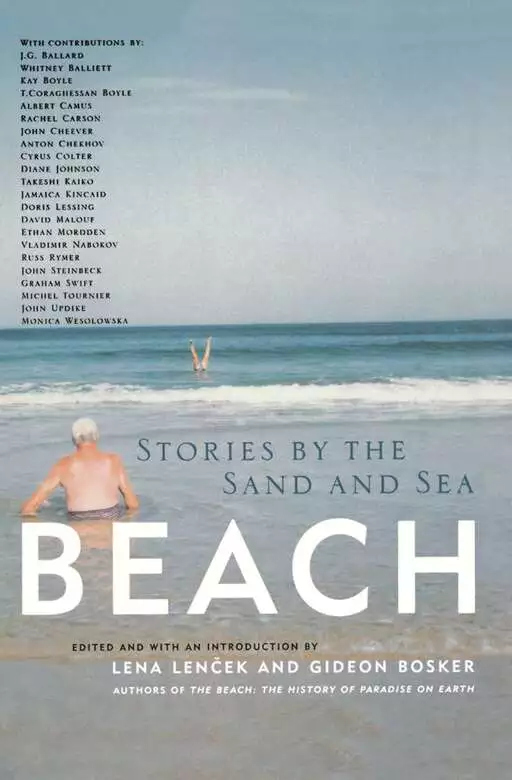

Beach

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

J. D. Salinger's "A Perfect Day for Bananafish," John Cheever's "Goodbye, My Brother," Doris Lessing's "Through the Tunnel": These and dozens of other beloved stories share the beach as their setting. In fact, it is remarkable how many of the finest writers have set stories and novels in whole or in part at the beach -- and how often they use this locale to explore the great themes of love, loss, death, family, and redemption. Beach brings together, for the first time, the very best of this literary tradition, including stories, novel excerpts, and narrative nonfiction.

Release date: July 21, 2009

Publisher: Da Capo Press

Print pages: 358

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Beach

Lena Lencek

It’s water time! Half submerged, at one with the great blue-green aqueous mystery below, you bob in the waves, something between fish, fowl, and terrestrial biped. The rest of you, exposed to sun and air from the neck up, swivels now one direction—toward the wide horizon—now the other, back to the shore, checking to see how far the tide has carried you from your day’s place on the beach. You’re on sensory overload, and you haven’t even broken any laws. You feel at one with the world—perhaps because the soothing riff of breakers, the rock and roll of waves, and the yielding warmth subliminally recall our secure uterine life before life.

Or perhaps it is the knowledge that the ocean is the wellspring of all organisms, and that the beach is the stage on which our ancestors first crawled into history. Slowly, you surrender to the rhythm and your mind goes as blank as the sky. You swim a few strokes, turn on to your back and float, letting the energy of the waves pass around and through you. After a while, you find your legs, shuffle out of the water, and flop onto a towel in a coma of ecstasy. Your head settles back into a sand pillow. A doze, perhaps, or, more likely, you adjust your sunglasses, angle the visor on your cap, open your book, and settle into nirvana. Beach bum goes beach brain. “There is rapture on the lonely shore,” wrote the British Romantic Lord Byron who, not coincidentally, was one of the greatest swimmers of all time. “There is society where none intrudes/ By the deep Sea, and music in its roar:/ I love not man the less, but Nature more.”

Ever since the British invented the beach holiday in the early eighteenth century, bathers have been packing books for a day by the sea. Back then, beachgoers were likely to also be armed with collapsible sun bonnets, watercolors, slippers, gloves, scarves, bizarre flotational devices, and parasols for their therapeutic sojourn—in winter, no less—on the North Sea. Healthy and wealthy young males took off on a Grand Tour to the shores of the Mediterranean, where they consulted leather-bound volumes of Homer and Virgil, and, later, Byron and Swinburne, as they gazed out over the sea and rhapsodized about the power and majesty of nature. In the nineteenth century, under a watery, winter sun, capacious beach chairs on the boardwalk at Deauville or Brighton would fill with readers tucked into novels by Austen, Flaubert, or Dickens.

The contents of the beach bag may have changed dramatically over the last two hundred years, but one item remains constant: the reading material. Books and beaches go together like gin and tonics, fish and chips, sun and tan. Look around a crowded beach—Bondi or Copacabana, Coney Island or St. Tropez, Hatteras or Miami, Laguna or the Hamptons—and you’ll see enough books to stock a respectable town library. People who ordinarily limit their reading to the backs of cereal boxes and stock market quotes are nose-deep in bestsellers, romances, and classics. What accounts for such bibliophilia? We like to think it’s the fact that on a purely psycho-sensory level, geology makes the beach a perfect site on which to unpack fantasies of pleasure and pain, glory and gain, and to tease out of hiding deep insecurities and secret, megalomaniacal passions. Put briefly, the beach makes us think, dream, and de-repress.

Storytellers since time immemorial have recognized this fact and given us a virtually inexhaustible supply of tales set on the beach. These are stories that explore the marvelous, aberrant things that humans do when they come to the shifting border of earth, water and sky, where all the elements that make up life come together, and where birth and death, creation and destruction are on permanent display. The very sand under our feet takes us far back in time and place. As Walter Benjamin wrote, “Nothing is more epic than the sea.”

Coming to grips with the uncertainties of existence, our ancestors concocted myths of beauties and beasts, gods and demons, heavenly rewards and divine retribution—all staged on the beach. Homer, Hesiod, Pindar,Virgil, Ovid, and countless, nameless bards have spun plots of supernatural metamorphoses, erotic transgressions, fateful loves, irresolvable strife, and miraculous homecomings that are lifted directly from the script of nature. In the feelings stirred by the perpetual shifting of land, water, sand, and clouds, the beach has inspired profound and beautiful poetry and prose. As Herman Melville wrote in Moby Dick, “There is, one knows not what sweet mystery about this sea, whose gently awful stirrings speak of some hidden soul beneath.”

Literary representations of the beach are as nuanced and myriad as its topography. The Biblical account of the Deluge, for example, casts the shore as a scarred, ravaged, and defiled landscape that bears the imprint of a wrathful divinity wreaking catastrophic judgment on a sinful humanity. At the other pole, the Greeks and Romans, and later, the writers of the Enlightenment, picture the beach as a paradise, uncorrupted by civilization, and inhabited by innocent, sensuous, and noble savages. Throughout the Middle Ages, the seashore figured as battleground and treacherous boundary where raiders unleashed rapine and terror, inspiring ballads that told of bold abductions and merciless appropriations.

Sentimental writers—from Addison, Burke, Macpherson, to Zhukovsky and Karamzin—sang the merits of uninhabited, rugged seashores for meditating on mortality, vanity, and the sublime. To Romantic poets, infatuated with the sea as the mirror of a psychologized nature, the beach spoke both of our wrenching solitude and our intimate connection with the universe and its elements. The beach has aroused wonder and curiosity, fear, awe, and exaltation in the minds and hearts of the world’s greatest thinkers, artists, and scientists. Modernists, like Joseph Conrad, Virginia Woolf, Thomas Mann, and James Joyce, saw the beach as the place where the scattered flotsam and jetsam of our subconscious washed up into consciousness and where we struggle to compose coherent narratives from the hopelessly scrambled fragments of our lives.

But, above all, the beach is where we have our most intense sexual experiences. After all, the inherent sensuality of the beach stimulates a thundering chromatic scale of sensations—tactile, visual, olfactory, gustatory, and kinetic. Every age and stage of our lives has its own fixed experience of the beach: courtship, honeymoon, parenthood, divorce, retirement. Budding adolescents discover the hidden bonus of the beach as a theater of erotic delights as they train their voyeuristic gaze on vast expanses of naked human flesh. Young men and women display their bodies in joyful mating rituals, while honeymooners embrace in the shade of solitary palapas, in musky oceanside motels, or luxurious beach hideaways. Mature conjugal love comes to renew itself—licitly, or more often, illicitly—by the sea. The divorced and the chronically mis-mated come for sexual renewal, and for one more chance on the erotic merry-go-around. In the end, there is an irreducible simplicity to life at the beach, which T. S. Eliot articulated when, in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” he pondered: “Do I dare to eat a peach? / I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.”

This anthology of great beach stories seeks to bring pleasure—sensual, aesthetic, and intellectual—to the glorious practice of reading on the beach. If there was a single principle guiding our selection of pieces, it was the idea that taken together, they should capture the torments and the ecstasies, the crises and epiphanies which so often transpire on the beach, the life-transforming moments, the rituals of family, love and friendship to which the beach plays host. From dozens and dozens of narratives, we’ve selected the most evocative and intelligent, the most revelatory sketches, and we’ve then submitted these to the goose-bumps-on-the-nape test recommended by Vladimir Nabokov as the most reliable guide to aesthetic perfection.

When it came to the final cut, the selections that raised the hairs on the backs of our necks, regardless of how often we’d read them, announced themselves as our “must haves.” Such, for example, are Rachel Carson’s incantatory “The Marginal World,” surely one of the most luminous pieces of writing on natural science, and John Steinbeck’s description, from Cannery Row, of the secret life of the tide pool, rendered with the sweeping scope and measured rhythm of Homeric epic.

Many of the stories evoke the entirely sensual happiness of Albert Camus’ sun-drenched “unconquerable summer” that culminates inevitably in some sort of apocalyptic expulsion from Eden. Such is T. Coraghessan Boyle’s glimpse at the Rabelaisian indulgences of mass-tourism. His “Mexico” wickedly charts the peripety of a gringo’s quest for R and R—Romance and Relaxation—in a south-of-the-border resort awash in gua-camole, margaritas, and sweat. Jamaica Kincaid’s chronicle of a torrid affair starts with the premise that the lover’s “mouth was like an island in the sea that was his face” and goes on to explore the sensual intelligence that lurks at the heart of hedonism. In Cyrus Colter’s “The Beach Umbrella,” the beach itself is the provocateur that seduces an upright, henpecked family man into lying and cheating just so that he too can have a little bit of that groin-tingling, gin-swilling, hip-swiveling bit of paradise that sprouts every Sunday on Chicago’s Thirty-first Street Beach.

Ever since imperial Rome, when seaside resorts such as Baiae attracted profligates, loose women, gamblers and gourmands to its sparkling shores, the beach has been synonymous with dissipation, hedonism, and vice. Every coastal nation has had its “dirty weekend destination,” a place of immorality and indolence, commercial sex and infidelity. The British had their Brighton, the French their Monte Carlo, the Americans, their Coney Island and Jersey shore, and the Russians their Yalta—where Anton Chekhov set, with consummate delicacy, “The Lady with the Pet Dog.”

Illicit doings, however, did nothing to diminish the beach’s reputation as a site for life-changing transitions, practically miraculous in nature, both religious and therapeutic. The theme of spiritual conversion informs Takeshi Kaiko’s “The Duel,” in which a young man comes to the sea to learn the unyielding law of life: kill or be killed, eat or be eaten. Diane Johnson’s “Great Barrier Reef” gives a sardonic twist to the image of the beach as the threshold of spiritual renewal. Here the beach is a tawdry outpost filled with ugly natives selling ugly souvenirs to ugly tourists, and the sea, seductively beautiful, enticingly warm, is in fact, “ riddled with poisonous creatures, deadly toxins, and sharks.” For Michel Tournier, the continual cycles of construction and deconstruction, revelation and concealment which transpire on the beach proffer the formula of regeneration to a couple in crisis. In “The Midnight Love Feast,” a philosophical dialogue on the nature of marriage, Tournier argues that the ideal condition of matrimony, like that of the beach, lies in its ephemerality. This same suspension of the ordinary underwrites the reconciliation between brothers and the cementing of family in Ethan Mordden’s “I Read My Nephew Stories.”

Like the proverbial pharmacon—a potent death-or-life dealing medical agent—the beach can both heal and harm. Such is the case in Vladimir Nabokov’s “Perfection” in which the Bolshevik Revolution deposits a meek, neurasthenic Russian on a Baltic beach with nothing but the clothes on his back and some mental baggage left over from a first-rate university education. As his adolescent ward soaks in the vital forces of the sun and the sea, the displaced tutor languishes and eventually perishes. More typical are the stories that render the beach as the symbolic setting for rites of passage, quasi-miraculous encounters with the self that are staged as near-death experiences. Graham Swift’s “Learning to Swim” shows us this ritual from the perspective of parents vying for formative control of their child. In Doris Lessing’s “Through the Tunnel,” the young boy’s epiphanic feat is a purely private act of self-generation, complete with passage through a figurative, submarine birth canal.

As Jonathan Raban so aptly put it, “The beach is a marginal place where marginal people congregate and respectable people come to do marginal things.” In John Cheever’s “Goodbye, My Brother,” blood lust and criminality swim to the genteel surface of sociability and erupt in a fratricidal encounter on the beach. Kay Boyle, in “Black Boy,” shows us the beach as a special place apart, where barriers of race and age and status are suspended and where unmediated encounters with other individuals are momentarily stripped of their social status. In “Turtle Turtle,” Monica Wesolowska describes the yearning and discontent of a coffee-colored Mayan Mexican, rocked by the sea, day in day out, staring with envy at gringo Mandarins as they debouche from fiberglass sailboats, buxom blondes in tow, beer and dope in hand, throwing money into the sea. Wesolowska has entered the mind of the disenfranchised, autochtonous noble savage reaching for the silver stud in the colonizer’s nostril, dreaming of becoming one of the Chucks or Bobs or Bills who seasonally migrate to the warm Mexican beaches to mate and perform enigmatic cultural rituals.

Whitney Balliett’s “A Floor of Flounders” offers one of the most enchanting portraits we’ve ever read of the marginal beach bum, the prototypical old man by the sea, who mediates the profligacy and simplicity of the beach to all urban comers, known and unknown. Against his “piscatorial idyll,” David Malouf’s “A Change of Scene” resonates as a sinister antithesis. As political upheaval touches a perfect Mediterranean island, it not only splinters the delicate harmony between outsider and native, but fractures the psychic integrity and sense of cultural continuity which the protagonists sought and fleetingly found in their littoral refuge. One of the sweetest and, for us, most exciting finds was the selection “Ancestral Houses” from Russ Rymer’s non-fictional American Beach, which reconstructs the lost world of a unique Black coastal resort, as presented through the haunting presence of master raconteur MaVynee Betsch.

Finally, we think that every anthology needs a bit of a chuckle and self-parody. So, for good measure, we’ve thrown in J. G. Ballard’s sci-fi “The Largest Theme Park in the World,” which explodes the fantasy of the endless summer by tracking the implications of a hypothetical “totalitarian system based on leisure” that fills the beaches of the world with professional hedonists. And a book of stories set at the beach would be seriously deficient if it were to omit the subject of the lifeguard, that icon of virile pulchritude who has preside at beaches, fueling female fantasies and, occasionally, descending, Perseus-like, to snatch a drowning swimmer from the jaws of death. John Updike’s “Lifeguard” inverts the usual optic according to which the tanned Adonis on the pedestal is the mute object of our gaze, and presents him instead from the inside out, as a delusional Narcissus scrutinizing our bloated, flawed, and dimpled bodies with arch distaste.

Compiling this anthology has given us the greatest pleasure. We hope that it will inspire in you, as it does in us, the depth of feeling and wonder that lies at the very core of the beach experience. If, in turning the pages of this book, you catch the distant perfume of the sea and, like Mary Betsch in Rymer’s American Beach, glimpse “the shape of sanctuary” in the image of the beach, then we will have succeeded in our goal.

—LENA LENČEK AND GIDEON BOSKER

the edge of the sea is a strange and beautiful place. All through the long history of Earth it has been an area of unrest where waves have broken heavily against the land, where the tides have pressed forward over the continents, receded, and then returned. For no two successive days is the shore line precisely the same. Not only do the tides advance and retreat in their eternal rhythms, but the level of the sea itself is never at rest. It rises or falls as the glaciers melt or grow, as the floor of the deep ocean basins shifts under its increasing load of sediments, or as the earth’s crust along the continental margins warps up or down in adjustment to strain and tension. Today a little more land may belong to the sea, tomorrow a little less. Always the edge of the sea remains an elusive and indefinable boundary.

The shore has a dual nature, changing with the swing of the tides, belonging now to the land, now to the sea. On the ebb tide it knows the harsh extremes of the land world, being exposed to heat and cold, to wind, to rain and drying sun. On the flood tide it is a water world, returning briefly to the relative stability of the open sea.

Only the most hardy and adaptable can survive in a region so mutable, yet the area between the tide lines is crowded with plants and animals. In this difficult world of the shore, life displays its enormous toughness and vitality by occupying almost every conceivable niche. Visibly, it carpets the intertidal rocks; or half hidden, it descends into fissures and crevices, or hides under boulders, or lurks in the wet gloom of sea caves. Invisibly, where the casual observer would say there is no life, it lies deep in the sand, in burrows and tubes and passageways. It tunnels into solid rock and bores into peat and clay. It encrusts weeds or drifting spars or the hard, chitinous shell of a lobster. It exists minutely, as the film of bacteria that spreads over a rock surface or a wharf piling; as spheres of protozoa, small as pinpricks, sparkling at the surface of the sea; and as Lilliputian beings swimming through dark pools that lie between the grains of sand.

The shore is an ancient world, for as long as there has been an earth and sea there has been this place of the meeting of land and water. Yet it is a world that keeps alive the sense of continuing creation and of the relentless drive of life. Each time that I enter it, I gain some new awareness of its beauty and its deeper meanings, sensing that intricate fabric of life by which one creature is linked with another, and each with its surroundings.

In my thoughts of the shore, one place stands apart for its revelation of exquisite beauty. It is a pool hidden within a cave that one can visit only rarely and briefly when the lowest of the year’s low tides fall below it, and perhaps from that very fact it acquires some of its special beauty. Choosing such a tide, I hoped for a glimpse of the pool. The ebb was to fall early in the morning. I knew that if the wind held from the northwest and no interfering swell ran in from a distant storm the level of the sea should drop below the entrance to the pool. There had been sudden ominous showers in the night, with rain like handfuls of gravel flung on the roof. When I looked out into the early morning the sky was full of a gray dawn light but the sun had not yet risen. Water and air were pallid. Across the bay the moon was a luminous disc in the western sky, suspended above the dim line of distant shore—the full August moon, drawing the tide to the low, low levels of the threshold of the alien sea world. As I watched, a gull flew by, above the spruces. Its breast was rosy with the light of the uprisen sun. The day was, after all, to be fair.

Later, as I stood above the tide near the entrance to the pool, the promise of that rosy light was sustained. From the base of the steep wall of rock on which I stood, a moss-covered ledge jutted seaward into deep water. In the surge at the rim of the ledge the dark fronds of oarweeds swayed, smooth and gleaming as leather. The projecting ledge was the path to the small hidden cave and its pool. Occasionally a swell, stronger than the rest, rolled smoothly over the rim and broke in foam against the cliff. But the intervals between such swells were long enough to admit me to the ledge and long enough for a glimpse of that fairy pool, so seldom and so briefly exposed.

And so I knelt on the wet carpet of sea moss and looked back into the dark cavern that held the pool in a shallow basin. The floor of the cave was only a few inches below the roof, and a mirror had been created in which all that grew on the ceiling was reflected in the still water below.

Under water that was clear as glass the pool was carpeted with green sponge. Gray patches of sea squirts glistened on the ceiling and colonies of soft coral were a pale apricot color. In the moment when I looked into the cave a little elfin starfish hung down, suspended by the merest thread, perhaps by only a single tube foot. It reached down to touch its own reflection, so perfectly delineated that there might have been, not one starfish, but two. The beauty of the reflected images and of the limpid pool itself was the poignant beauty of things that are ephemeral, existing only until the sea should return to fill the little cave.

Whenever I go down into this magical zone of the low water of the spring tides, I look for the most delicately beautiful of all the shore’s inhabitants—flowers that are not plant but animal, blooming on the threshold of the deeper sea. In that fairy cave I was not disappointed. Hanging from its roof were the pendent flowers of the hydroid Tubularia, pale pink, fringed and delicate as the wind flower. Here were creatures so exquisitely fashioned that they seemed unreal, their beauty too fragile to exist in a world of crushing force. Yet every detail was. functionally useful, every stalk and hydranth and petal-like tentacle fashioned for dealing with the realities of existence. I knew that they were merely waiting, in that moment of the tide’s ebbing, for the return of the sea. Then in the rush of water, in the surge of surf and the pressure of the incoming tide, the delicate flower heads would stir with life. They would sway on their slender stalks, and their long tentacles would sweep the returning water, finding in it all that they needed for life.

And so in that enchanted place on the threshold of the sea the realities that possessed my mind were far from those of the land world I had left an hour before. In a different way the same sense of remoteness and of a world apart came to me in a twilight hour on a great beach on the coast of Georgia. I had come down after sunset and walked far out over sands that lay wet and gleaming, to the very edge of the retreating sea. Looking back across that immense flat, crossed by winding, water-filled gullies and here and there holding shallow pools left by the tide, I was filled with awareness that this intertidal area, although abandoned briefly and rhythmically by the sea, is always reclaimed by the rising tide. There at the edge of low water the beach with its reminders of the land seemed far away. The only sounds were those of the wind and the sea and the birds. There was one sound of wind moving over water, and another of water sliding over the sand and tumbling down the faces of its own wave forms. The flats were astir with birds, and the voice of the willet rang insistently. One of them stood at the edge of the water and gave its loud, urgent cry; an answer came from far up the beach and the two birds flew to join each other.

The flats took on a mysterious quality as dusk approached and the last evening light was reflected from the scattered pools and creeks. Then birds became only dark shadows, with no color discernible. Sanderlings scurried across the beach like little ghosts, and here and there the darker forms of the willets stood out. Often I could come very close to them before they would start up in alarm—the sanderlings running, the willets flying up, crying. Black skimmers flew along the ocean’s edge silhouetted against the dull, metallic gleam, or they went flitting above the sand like large, dimly seen moths. Sometimes they “skimmed” the winding creeks of tidal water, where little spreading surface ripples marked the presence of small fish.

The shore at night is a different world, in which the very darkness that hides the distractions of daylight brings into sharper focus the elemental realities. Once, exploring the night beach, I surprised a small ghost crab in the searching beam of my torch. He was lying in a pit he had dug just above the surf, as though watching the sea and waiting. The blackness of the night possessed water, air, and beach. It was the darkness of an older world, before Man. There was no sound but the all-enveloping, primeval sounds of wind blowing over water and sand, and of waves crashing on the beach. There was no other visible life—just one small crab near the sea. I have seen hundreds of ghost crabs in other settings, but suddenly I was filled with the odd sensation that for the first time I knew the creature in its own world—that I understood, as never before, the essence of its being. In that moment time was suspended; the world to which I belonged did not exist and I might have been an onlooker from outer space. The little crab alone with the sea became a symbol that stood for life itself—for the delicate, destructible, yet incredibly vital force that somehow holds its place amid the harsh realities of the inorganic world.

The sense of creation comes with memories of a southern coast, where the sea and the mangroves, working together, are building a wilderness of thousands of small islands off the southwestern coast of Florida, separated from each other by a tortuous pattern of bays, lagoons, and narrow waterways. I remember a winter day when the sky was blue and drenched with sunlight; though there was no wind one was conscious of flowing air like cold clear crystal. I had landed on the surf-washed tip of one of those islands, and then worked my way around to the sheltered bay side. There I found the tide far out, exposing the broad mud flat of a cove bordered by the mangroves with their twisted branches, their glossy leaves, and their long prop roots reaching down, grasping and holding the mud, building the land out a little more, then again a little more.

The mud flats were strewn with the shells of that small, exquisitely colored mollusk, the rose tellin, looking like scattered petals of pink roses. There must have been a colony nearby, living buried just under the surface of the mud. At first the only creature visible was a small heron in gray and rusty plumage—a reddish egret that waded across the flat with the stealthy, hesitant movements of its kind. But other land creatures had been there, for a line of fresh tracks wound in and out among the mangrove roots, marking the path of a raccoon feeding on the oysters that gripped the supporting roots with projections from their shells. Soon I found the tracks of a shore bird, probably a sanderling, and followed them a little; then they turned toward the water and were lost, for the tide had erased them and made them as though they had never been.

Looking out over the cove I felt a strong sense of the inter-changeability of land and sea in this marginal world of the shore, and of the links between the life of the two. There was also an awareness of the past and of the continuing flow of time, obliterating much that had gone before, as the sea had that morning washed away the tracks of the bird.

The sequence and meaning of the drift of time were quietly summarized in the existence of hundreds of small snails—the mangrove periwinkles—browsing on the branches and roots of the trees. Once their ancestors had been sea dwellers, bound to the salt waters by every tie of their life processes. Little by little over the thousands and millions of years the ties had been broken, the snails had adjusted themselves to life out of water, and now today they were living many feet above the tide to which they only occasionally returned. And perhaps, who could say how many ages hence, there would be in their descendants not even this gesture of remembrance for the sea.

The spiral shells of other snails—these quite minute—left winding tracks on the mud as they moved about in search of food. They were horn shells, and when I saw them I had a nostalgic moment when I wished I might see what Audubon saw, a century and more ago. For such little horn shells were the food of the flamingo, once so numerous on this coast, and when I half closed my eyes I could almost imagine a flock of these magnificent flame birds feeding in that cove, filling it with their color. It was a mere yesterday in the life of the earth that they were there; in nature, time and space are relative matters, perhaps most truly perceived subjectively in occasional flashes of insight, sparked by such a magical hour and place.

There is a common thread that links these scenes and memories the spectacle of life in all its varied manifestations as it has appeared, evolved, and sometimes died out. Underlying the beauty of the spectacle there is meaning and significance. It is the elusiveness of that meaning that haunts us, that sends us again and again into the natural world where the key to the riddle is hidden. It sends us back to the edge of the sea, where the drama of life played its first scene on earth and perhaps even its prelude; where the forces of evolution are at work today, as they have been since the appearance of what we know as life: and where the spectacle of living creatures faced by the cosmic realities of their world is crystal clear.

the creation of a united Europe, so long desired and so bitterly contested, had certain unexpected consequences. The fulfilment of this age-old dream was a cause of justified celebration, of countless street festivals, banquets and speeches of self-. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...