- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

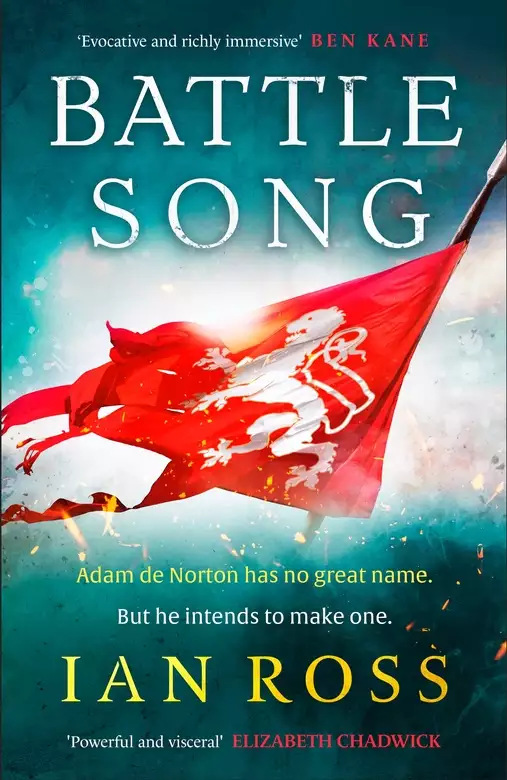

Synopsis

'There is a fury in England that none shall suppress - and when it breaks forth it will shake the throne'

1264

Storm clouds are gathering as Simon de Montfort and the barons of the realm challenge the power of Henry III. The barons demand reform; the crown demands obedience. England is on the brink of civil war.

Adam de Norton, a young squire devoted to the virtues of chivalry, longs only to be knighted, and to win back his father's lands. Then a bloody hunting accident leaves him with a new master: the devilish Sir Robert de Dunstanville, who does not hesitate to use the blackest stratagems in pursuit of victory.

Following Robert overseas, Adam is introduced to the ruthless world of the tournament, where knights compete for glory and riches, and his new master's methods prove brutally effective.

But as England plunges into violence, Robert and Adam must choose a side in a battle that will decide the fate of the kingdom. Will they fight for the king, for de Montfort - or for themselves?

Searingly vivid and richly evocative, Battle Song is tale of friendship and chivalry, rivalry and rebellion, and the medieval world in all its colour and darkness.

(P) 2023 Hodder & Stoughton Limited

Release date: March 30, 2023

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Battle Song

Ian Ross

January 1262

The forty-sixth year of King Henry III

Epiphany’s eve, and snow lay on the slope of the castle mount. Boisterous, alight with spiced ale, the three young men scraped it up with their hands and packed it onto the steps that descended from the upper hall. With their heels they rubbed it to a smooth grey slick. Then they leaned against the railing of the bridge that spanned the moat, breath steaming, curbing their laughter as they waited for their prey.

A figure appeared at the top of the steps, lean and hunched against the cutting breeze as he emerged from the shelter of the hall. He was a squire like them, eighteen years old, with cropped hair and a short tunic. Hurrying down the steps, his arms burdened with folded linens, he did not see the trap until it was too late. Then his foot skated out from beneath him and he was tumbling backwards, the stone step cracking into his spine as he fell. Their laughter was raucous in the frigid air.

‘Look at him!’ the biggest of the three cried. ‘Look at him, writhing like a worm! What’s this worm called?’

‘His name’s Adam de Norton,’ said one of the others.

‘Adam de Nought!’ the big youth said with a grin, dropping from French into the English of the common people. ‘Adam de Nothing – he comes from nothing! Was his father a nothing?’

‘A Welshman killed his father,’ the third of them said, stamping his feet to keep warm.

Sprawled on the icy steps, Adam de Norton felt the pain bursting through him. The humiliation too. The clean linens he had been carrying were scattered in the dirt and the muddy snow; they were cloths for the feasting tables, and he knew he would be punished for spoiling them. Then he heard their words, and fierce anger flared in his blood.

‘Let’s see if this worm can swim,’ the big youth was saying, eager in his malice. ‘Perhaps the moat’s a good place for him?’

‘Leave him, Gerard,’ one of the others said. By his tone, he was already having misgivings about this game. Adam turned his head and blinked; he had considered that one a friend.

The second youth he knew as well, a fellow squire of the household. But the leader, the one who had clearly bullied them into this sport, was a stranger to him. Gerard was stocky and thick-fleshed, with a red face and a snub nose and very small eyes. On his white tunic was sewn a red diagonal cross-lattice. A heraldic device, but Adam did not recognise it; Pleshey was full of strangers who had come for Earl Humphrey’s winter court.

Gerard advanced a pace closer. Adam was still lying on the steps, his muscles bunched. He felt the pain in his back and head, but the ache was fading fast. He knew that Gerard wanted more. He wanted to assert himself, and intimidate his followers.

‘Leave him – someone’s coming!’ said the third squire, but his friend remained sitting on the bridge railing, watching avidly. Gerard took another stamping step towards Adam, reaching down to seize his shoulder.

With a surge, Adam pushed himself upright, darting clear of the young man’s clumsy grab and getting his feet beneath him. Anger drove him; without thinking, he was swinging his fist with the momentum of his movement, a wide reaping blow that smacked meatily into the centre of Gerard’s face.

For a few long moments nobody made a sound. Birds cried harshly from along the moat. Woodsmoke scented the air. Gerard was still standing, bent forward and clutching his face. Spots of blood spattered at his feet, jewel-bright in the snow.

‘By dode!’ he managed to say. ‘He boke by dode!’

The two other squires were motionless, staring in fascinated shock. Then Gerard straightened, let his hands drop from his bloodied face, and roared as he flung himself at Adam.

They went down together, locked in combat. Adam was numb to Gerard’s savage blows on his chest and face. He knew he had to win. His adversary was two stone heavier than him and driven by pain and outraged pride, but Adam was agile and angry. He dragged his right arm free of Gerard’s crushing grip and slammed two punches into the man’s face, bursting the remains of his nose. His third blow struck his eye, and his fourth struck the stretched column of his throat. Gerard had his thumbs clamped over Adam’s face, trying to gouge at his eyes. But Adam had rolled on top now, shoving himself clear. He swung his fist, and slammed another blow into Gerard’s right eye socket. Blood sprayed across the dirty snow, and he felt his attacker’s grip slackening. Again he struck, and again, fury powering his blows.

‘Enough!’ somebody was shouting. ‘Enough! Stop this!’ Men were hurrying from all directions, their cloaks and mantles flapping in the cold air.

Adam barely felt the arms that hauled him out of the fight.

*

‘You don’t know who that was, do you?’ the cook’s mate said, sitting under the back porch of the kitchen plucking geese. ‘Or rather, whose that was . . . Whose squire, I mean.’

‘No,’ Adam replied. He set another log on the block, straightened, then swung the axe down. His whole body ached, but he would not let it show. ‘I don’t care,’ he said. The air in the kitchen yard was so cold it hurt to breathe, but he was sweating.

‘You should care!’ the cook’s mate said. ‘That lad you mauled yesterday, young sir, is squire to Robert de Dunstanville, that’s who!’

Natural John, Earl Humphrey’s fool, was squatting beside the basket of goose down, trailing his fingers in the soft feathers. He raised his head at the name and whined like a dog.

‘Dunstanville, hah!’ said the porter, rolling a keg from the bakehouse door. ‘He’s here too, is he?’ He paused in his work to make a holy warding sign.

‘I said I don’t care,’ Adam told them. He swung his axe again, splitting another log into shards. Chopping wood for the kitchen fire was well beneath even the lowest of squires, but this was his punishment for brawling on the eve of a holy day. A morning of menial chores, while the rest of the household rode out to the hunt.

‘Quiet down, Natural John,’ the cook’s mate snapped. The fool was still whining, rocking on his haunches. ‘Robert de Dunstanville,’ he said to Adam, gesturing with a handful of feathers, ‘is not a man to cross. There are tales about him.’

‘Tales?’ Adam said, finally relenting. He propped his axe on the chopping block and leaned on it, breathing hard. A blizzard of splintered wood lay all around him.

‘They say he murdered a priest,’ the porter said from the doorway. ‘Cut him down right on the steps of his own altar! He was excommunicated for that, and would have been outlawed except for the pleas of Lord Humphrey and his grace the Earl of Winchester. But his lands were seized anyhow, and now he wanders the earth like a carrion dog . . .’

‘They say,’ the cook’s mate broke in, lowering his voice, ‘that he was taken captive by the Saracens, and they forced him to renounce Christ, and now he is the Devil’s Man! You see that red lattice he bears as his emblem? That’s the devil’s fiery flaming griddle, that he uses to roast sinners down in hell!’

Natural John let out a keening wail and buried his head in the basket of goose down. Adam was unmoved. He remembered the red-on-white lattice from Gerard’s tunic – he had seen it on a shield as well. A simple heraldic design that he knew well from his lessons. Argent fretty gules. Something else too: a lion on a red quarter, and a blue charge. In a quadrant gules a lion passant gardant or, with a label of three points azure . . .

‘So why does Lord Humphrey admit him to his court?’ Adam asked. He stooped down, feeling the ache of his bruised ribs, and set another log on the block.

‘Because Robert de Dunstanville is Lord Humphrey’s bastard offspring, that’s why,’ the porter said. ‘Or so they say,’ he added hurriedly, with a glance towards the gateway. ‘Lord Humphrey got him on old Saer de Quincy’s youngest daughter, who was wed to the brother of Walter de Dunstanville, the Baron of Castlecombe.’

Adam sniffed tightly, not wanting to appear impressed. The porter prided himself on his intimate knowledge of family connections among the nobility.

‘Well, he’ll be leaving again soon enough,’ the cook’s mate said, going back to his plucking with renewed vigour. ‘Soon as the feasting’s done he’ll be away, and his misbegotten squire and light-fingered servants with him . . . Off to wave a lance on the tourney fields overseas – that’s how he gains his bread nowadays, when he isn’t living off his betters . . .’

‘And God be praised once we’re rid of them all,’ the porter muttered.

But Adam was no longer listening. He split another log, burying the axe blade in the block, then pulled the steel free with a savage tug. Heat was flowing through him, despite the chill of the morning. Gerard was equally to blame for the fighting the day before, and everyone knew it, but only Adam was being punished. The other squire was a guest at Pleshey, and had Adam not struck the first blow? Besides, a badly broken nose and two black eyes looked worse than mere bruises. Adam had spied the young man leaving the chapel after mass that morning, and his face had been shockingly battered and livid. Gerard had even had trouble mounting his horse. But he and his depraved master would ride with Earl Humphrey on the hunt, and only Adam would take the blame. The injustice was sickening.

For nearly five years Adam had served in the household of Earl Humphrey de Bohun, riding with the retinue between the earl’s many estates and castles, but still he was the lowest of the squires. Lord Humphrey himself had scarcely said a word to him in all that time, except to issue orders. Often he seemed uncertain of Adam’s name. Then again, why should he not be? There were over thirty squires in the household, some of them from great and powerful families. Adam himself had no great name, no fortune or ancestral estate. His father had been a common serjeant, knighted by the king for valour during the fighting in Aquitaine; he had died in Wales, serving in Lord Humphrey’s retinue, and the earl had taken Adam in as a favour to his widowed mother. Now his mother too was dead, and strangers tenanted his father’s lands.

Earlier that morning, watching from the sidelines as Lord Humphrey’s household and guests rode out to the hunt, Adam had been all too aware of his own insignificance. He was closer to the servants than to the other squires. The noisy swirl of horses and dogs, shouting men and screeching horns had poured from the bailey yard, out across the bridge that spanned the moat and away into the dimness of a cold winter’s dawn, leaving the castle to the servants and the womenfolk, and to Adam.

He took a few moments to collect up the cords of cut wood, his fingers too numbed to feel the splinters. The knuckles of both hands were still grazed, the skin split and blackened. He stacked the wood, sucked at his thick lip, then picked up the axe once more.

Counting the earl’s household, the castle servants, the guests, and the resident paupers, well over two hundred people lived within the walls and moats of Pleshey. Adam knew he could make no claims for special treatment. But it angered him that he should have to toil like a common labourer, while Gerard was pardoned. While a murderous Christ-despising renegade like Robert de Dunstanville was treated as an honoured guest, merely due to some accident of birth. What sort of world was this, he seethed, when the godless and the vile were honoured and rewarded, and the honest must suffer for the crimes of others? It was not the first time he had mulled over these things. But now his grievance had a sharply personal edge.

He set about the stack of wood once more, hacking the axe down into the block with a cold destructive fury. Only when he paused, blinking the sting of sweat from his eyes, did he notice the stillness around him.

Voices came from outside the gateway to the yard, and the sound of horses and dogs. It was far too early for the hunters to have returned; barely an hour had passed since their departure. Then two men came shoving through the gateway, bearing something between them. A dog weaved around their legs, tail thwacking. Another two men followed; it was a plank they were carrying. A plank with a body tied to it.

‘. . . fell from the saddle when he was struck by a branch,’ one of the men was saying to the group at the kitchen door. ‘His foot caught in the stirrup and the horse dragged him at the gallop . . . was dead by the time we got to him!’

‘What did they expect?’ another man said. ‘State of him this morning . . .’

The yard was crowded now, a throng pressing through the gateway and surrounding the body as the bearers set it down. Adam pushed his way between them, his heart tight in his chest. He already knew what he would see.

The body was battered almost beyond recognition, the face a black and bloody mask. Adam’s throat tightened as he imagined what had happened: the rider dragged by the panicked horse, whipped and smashed by thorns and tree-trunks, likely kicked by the hooves too. With any luck his neck had snapped immediately. The men crowding round the body hissed and sucked their teeth. Natural John was capering in the kitchen doorway, wailing in anguish.

But what drew Adam’s eye was the badge stitched to the dead man’s breast. A diagonal red lattice on white. Argent fretty gules.

‘Poor lad could barely see where he was riding anyway,’ somebody said. ‘Eyes swollen half shut, and not in his right senses either. They should never have allowed it, after the pummelling he took yesterday . . .’

And as the guilt consumed him, Adam felt himself drawing back from the throng, letting them close in and block the sight of Gerard’s mangled body. The axe hung loose from his fist, and when he glanced to his right he saw a group of riders outside the gateway to the yard, peering in. One of them, wrapped in a thick cloak, stared back at him with accusation in his eyes. A face like a blade, and a short pointed beard. Adam’s blood slowed. He knew who this must be.

Robert de Dunstanville. The Devil’s Man.

*

The great hall of Pleshey Castle was warm and smoky, the glow of the fire in the central hearth driving back the encroaching gloom of winter. Three long trestle tables stood around the hearth, each covered with linens laundered to fresh whiteness, and the household and guests filled the benches. Adam de Norton took his place on the fourth side of the long hall, between the doors, where the meats were laid to be dressed and carved. He was one of four squires appointed to serve the high table, where Lord Humphrey himself sat. Despite the tragic events of the morning, and the premature end of the hunt, Adam seemed to have been forgiven his lapse of the day before.

‘Did you see him though, when they brought him in?’ whispered the squire beside him. Ralph de Tosny was one of the few in the household that Adam considered a friend.

‘Briefly,’ he said, wincing.

‘I was away with the leading hunt,’ Ralph whispered. ‘But I heard what had happened. Lord Humphrey was not at all happy – they’d only just sounded the chase, and in the confusion the dogs lost the spoor—’

Then the steward hissed for them to be silent.

A blart of noise, and a group filed into the hall bearing the main course between them. Two servants carried the massive platter holding the roast boar, decked with festive holly and ribbons in the Bohun colours of blue, white and gold. Not a real wild boar, of course – such creatures were seldom to be found in England nowadays, even in the game parks of great magnates – but a huge pig dressed to look like one. Its bulging flanks dripped with honey, and its gaping snout was stuffed with a blackened apple. Musicians accompanied the platter-bearers on bagpipes, vielle and tabor as they made a round of the hall, circling the central hearth to display the boar to the diners, before taking it back to the table to be carved and dressed with piquant sauces. Adam was uncomfortably reminded of the dead man tied to the plank that morning; surely others made the connection, but none said a word about it. He tried to put the image from his mind as he carved the meat and carried the platter up to the high table.

Lord Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford and Essex, Constable of England and one of the greatest magnates in the kingdom, was in his mid-fifties, but still a powerful man and a famed warrior. He gripped his wine goblet with a corded hand, and scrutinised his assembled guests through hard and narrowed eyes. Only occasionally did his lips twitch a smile, as some words of jest or praise reached him. He spared not a glance as Adam stepped up with the platter and served the meats; Adam was glad of that, and gladder still to return to his place at the far end of the hall.

Further courses were already arriving from the kitchens. Besides the boar-pig there were rolls of stuffed venison, a rack of roasted geese and ducks, veal rolled in almonds, roast herons and partridges, glazed sheep’s heads and lark’s tongues in jelly, and pies stuffed with game and fowl. A torrent of meats, as if all the beasts of the wild and the birds of the air had hurried forth to fill the gullets of the diners. Between courses, the squires made their rounds with silver ewers of water and jugs of wine, fresh white loaves still warm from the ovens, and the big voider baskets to collect the uneaten food and dripping trenchers. Lord Humphrey’s collection of paupers were already gathered in the kitchen yard, waiting for their allocation of alms from the master’s table.

Soon the feasting would be done. The hippocras and wafers would be served, Natural John would appear in one of his amusing costumes, and then Adam himself could eat. Perhaps before the hall was cleared there would be music, or a poet to recite tales of chivalry. Lord Humphrey enjoyed hearing singing after dinner, particularly rousing songs, so everyone could join in the chorus. But Adam had always preferred to hear stories; since childhood he had loved the romances of Arthur and his knights, of Roland and Alexander, and of Godfrey de Bouillon.

As a boy, listening to the poets in the warm shadows of the hall, he would let his mind drift to scenes of distant lands and great deeds of prowess, beautiful ladies and chivalric champions. Picturing the young Roland, knighted by Charlemagne on the battlefield of Aspremont and girded with the sword Durendal that he had captured from the King of the Saracens, he would imagine becoming such a champion himself. A true heart, he had told himself, and firm convictions could win great rewards on earth besides in heaven. Childish fantasies, they seemed to him now. Roland, he guessed, had never split his knuckles brawling in the dirt. Godfrey de Bouillon had never been ordered to chop firewood either.

Even to be knighted, Adam thought, was a near-impossible dream. Knighthood had to be earned. And where were the opportunities for that, in the packed clamour of Earl Humphrey’s court? He knew of men who had served twenty years or more as squires and had never been granted the accolade. That was his own likely fate, he told himself, and found a strange grim pleasure in the bleakness of his mood.

Ralph’s nudge broke him from his thoughts. ‘The lord’s companions are running short,’ the other squire whispered. ‘I’ll take the wine, you carve.’

Adam felt the heat from the fire on his back as he took up the knives and carved the slices of pork. His senses were flooded with the scents of roasted meat, and his empty stomach tightened. When the platter was filled he dressed it with a ladle of peppery sauce and carried it up to the high table. Lord Humphrey was listening to his wife, the countess, with his chancellor leaning across to offer advice. Adam hung back, waiting for their hushed conference to be concluded.

‘But I’d heard,’ a voice said across the hall, ‘that the King of France had prohibited the sport – is that not so?’

‘He did, last year,’ another voice said, and Adam’s shoulders tensed. He had been trying not to glance in the direction of the right-hand table, but he knew to whom that bitter, cynical-sounding voice must belong. ‘At the time, King Louis believed that the Pope was about to call a new expedition to the Holy Lands. But now the Pope is dead, there is no new expedition, and doubtless the ban will be lifted before long. It only covers the French crown domains anyway – tournaments continue in the county of Champagne, and in Flanders and Burgundy, and the Empire too of course.’

‘Well, I consider King Louis very wise in banning them,’ one of the priests at the table primly declared, ‘and our King Henry likewise. As our holy father the Pope says, tournaments are nothing but vanity for the participants, and the cause of turbulence and unnecessary bloodshed too . . .’

‘And the Pope knows more than most about causing turbulence and unnecessary bloodshed, I suppose,’ Robert de Dunstanville said with a smile.

Before the priest could summon a reply, Adam saw that the countess and the chancellor had ceased their deliberations. He stepped up quickly to the high table and began serving the meat onto the dish that Lord Humphrey shared with his wife. After a few slices, the earl raised his hand, then gestured to one of the side tables. ‘Sir Robert,’ he called. ‘Some meat from my platter?’

Adam tensed, willing himself to appear unconcerned as he passed down the right-hand table to stand before Robert de Dunstanville. He looked down as he served the meat and caught the man’s narrowed eye. Then, as he made to step back, de Dunstanville flashed out his hand and seized Adam’s wrist in a clamping grip. He twisted his arm, turning Adam’s hand to expose the battered knuckles.

‘So,’ he said, with a sneer in his voice. He was facing the fire, but Adam’s shadow cloaked him in darkness. His large eating knife lay beside his trencher.

‘I was sorry to hear of what happened to your squire, sir,’ Adam managed to say.

‘Were you?’ de Dunstanville replied quietly, still gripping Adam by the wrist. ‘Perhaps you were. But perhaps you revelled in it a little too, hmm? Any man would, I think.’

Abruptly he released his grip, and Adam stepped back from the table. ‘Bring me wine,’ the knight told him, raising his empty cup. ‘And I want to see you pour it yourself.’

Quickly Adam paced back down the hall and took the silver jug of wine from Ralph. By the time he returned, the conversation had resumed along the table.

‘Lord Edward is in France now, I believe?’ one man said. ‘Or he will be soon – he’s been wintering in Gascony, I think. He’ll surely be in Burgundy for the tournaments.’

Adam stepped up to the table once more; Robert de Dunstanville ignored him as he poured the wine.

‘And you’ll meet with him while you’re overseas?’ another man asked the knight.

‘If our paths should cross, I shall not avoid him, no.’

The cup was filled, and Adam made to turn away, but de Dunstanville halted him with a raised finger, still not glancing in his direction.

‘And what of our other . . . friend, who is in France?’ Earl Humphrey said from the high table. The other voices around the hall fell abruptly silent. ‘Will you see him too?’

‘I cannot say, my lord,’ de Dunstanville said with a shrug. ‘I believe Simon de Montfort is currently a guest of the King of France, and keeps to his estates.’

‘Just be careful,’ Earl Humphrey said, with a vague circling motion of his hand. Adam recalled the story the servants had told, that Robert de Dunstanville was their lord’s bastard son. ‘Avoid becoming embroiled in any schemes,’ the earl went on. ‘Avoid mischief, Robert. I can say no more to you.’

The knight inclined his head in polite acknowledgement. Adam was already backing away along the table, the wine jug clasped before him.

‘Well, you need not worry,’ de Dunstanville said with a laugh. ‘I shall not be tourneying at all in my present condition! As you see, my lord, as of today I have no squire. What use is a tourneying knight without a squire?’

‘A sad business,’ Earl Humphrey gruffly agreed. ‘Unfortunate! I feel, of course, somewhat responsible. No, really . . .’ he went on, as a chorus of dissenting voices came from the other tables. ‘Really, I would not allow a guest to leave here inconvenienced or unprepared, after such a sad event. That one – you there!’

With a tight shock, Adam realised that the earl was gesturing towards him.

‘We might hold him too at least partly responsible,’ he said to Robert de Dunstanville. ‘Would he serve as your squire in the place of the other?’

Adam turned in surprise and the knight’s searching gaze caught him once more.

‘Maybe,’ de Dunstanville said. ‘He looks a little scrawny for his age. But he bested my squire Gerard, who was no kitten. How clever is he at his duties?’

‘Not for me to say,’ Earl Humphrey replied. ‘Marshal,’ he called down the table, ‘how proficient is the lad?’

The marshal of the household gave Adam an appraising squint. ‘Oh, he knows a horse from a hound,’ he said. ‘And his skill at arms is no worse than the rest. Which is to say, good enough.’

‘Then maybe he’ll suffice,’ de Dunstanville said with a shrug.

And Adam stood motionless, conscious suddenly of the gathering silence around him, the throng at the tables all staring at him, the faint crack and hiss of the burning wood in the central hearth. And he knew, as the pulse quickened in his throat and his chest grew tight, that his life was now in the hands of Robert de Dunstanville.

Chapter 2

They left Pleshey before daybreak and rode westwards on lanes of frozen mud. The pale light of dawn exposed a flat landscape under hoarfrost, bare black trees scratching the sky, mist rising from the thawing fields. A few hooded figures in the middle distance gathered wood or hacked at the soil, but otherwise the world appeared deserted. Robert de Dunstanville rode at the head of his little retinue on a palfrey, with his iron-grey destrier thudding along beside him. Adam followed, on a plain rouncey that Lord Humphrey had provided from his own stable. Two sumpter horses came behind him laden with baggage, led by a weaselly-looking servant named Wilecok. At the rear upon a heavy cob was de Dunstanville’s serjeant, a weathered man-at-arms of uncertain age called John Chyld. His chin was thick with greying bristles, he wore a grimy linen coif pulled down to his eyes, and as he rode he chewed on a roasted pig’s foot taken from the kitchens.

There had been no ceremony to their departure. The castle had still been in darkness when they left, most of the occupants wrapped in their bedrolls. Only Natural John had come forth to bid Adam a stammering farewell – fitting that Lord Humphrey’s fool was the only member of the household to do so. Adam was strangely moved all the same. In the four days since the Epiphany feast, he had felt himself frozen out of the community at Pleshey. Even former friends like Ralph had seemed to avoid him, as if he were already tainted by whatever curse or malediction Robert de Dunstanville bore. As if his soul were already blackened.

Now Adam could observe him more closely, he saw that his new master was around thirty years old, and as lean and hard as a rawhide strap. He was dressed in cloak and tunic of common dark blue serge, but the sword belted at his side had a silvered hilt and fittings. As he rode he tugged and teased at his short beard, or stroked at his moustaches with his thumb, as if he were lost in complex thoughts. He said nothing, to Adam or to anyone else, for the first few hours. Only when they were passing through Roding did he call a halt to rest the horses and break their fast.

‘So,’ he announced, as they sheltered in the lee of a blackthorn thicket and chewed on their tough bread and smoked ham. ‘You’ll have heard folk talking about me, back at Pleshey. What did they say?’

Adam merely shrugged. He heard John Chyld make a kissing sound against his teeth, and Wilecok was grinning to himself. But if the knight could be taciturn, so could he.

‘You’re right to be wary of me, boy,’ Robert de Dunstanville said, in a low tone. ‘I’m a man of fierce and bloody temper, and I do not like to be crossed. But if there are lies being told of me, I want to know of them. So – I asked you a question. Speak.’

I will not fear this man, Adam told himself. I will not let him intimidate me.

‘They say,’ he replied, the words drying his mouth, ‘that you murdered a priest. And you’re excommunicated.’

Sir Robert barked a laugh. ‘That priest deserved what he got!’ he said. ‘He disrespected my late wife’s memory. The excommunication I paid off with a pilgrimage to Pontigny last year. What else?’

‘They say you were a captive of the Saracens. And they forced you to deny Christ.’

For a moment Sir Robert appeared to consider this. ‘True enough, I was,’ he said with a sniff. ‘But the Saracens never tried to break my faith. The clergy of this very kingdom have tested it sorely indeed though.’

John Chyld let out a wheezing laugh and shook his head again.

‘And they say . . .’ Adam blurted out, feeling an angry heat rising through him, ‘that your lands were seized from you, and you roam the earth like . . . like a carrion dog.’

Robert de D

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...