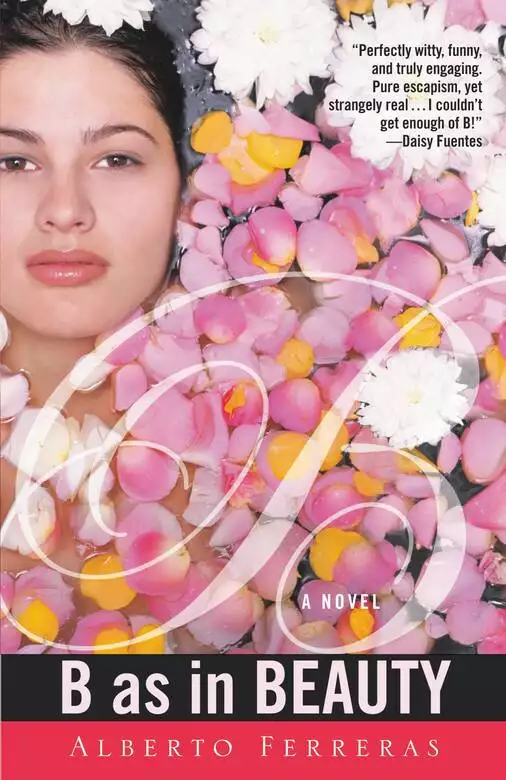

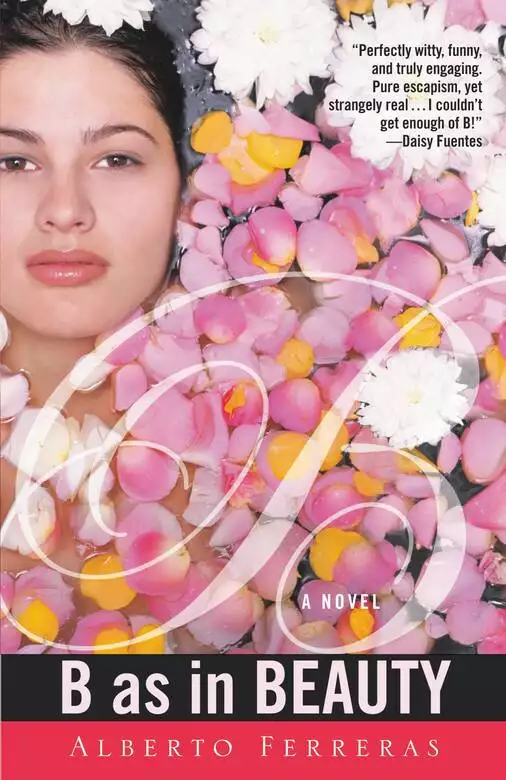

B as in Beauty

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Everyone in the world, it seems, is either prettier or thinner (or both) than Beauty Marie Zavala. And the only thing "B" resents more than her name is the way others judge her for the extra 40 pounds she can't lose. At least she has her career. Or did, until she overhears her boss criticizing her weight and devising a scheme to keep her from being promoted. Enter B's new tax accountant, a modern-day matchmaker determined to boost B's flagging self-esteem by introducing her to rich, successful men who will accept her for who she is. As B's confidence blossoms, so do her fantasies of revenge. But will B find true happiness or true disaster when she unwittingly falls for the one guy she shouldn't?

Release date: April 4, 2009

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 350

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

B as in Beauty

Alberto Ferreras

I eat too much, I don’t exercise enough, I combine the wrong foods, I eat late at night, etc. The truth is that I watch carefully

what I eat, I exercise every day, and I’d never eat carbohydrates past 7 p.m. So there goes that theory.

There’s also the “I take after my aunt” theory—which implies that I’m fat like my aunt Chavela because we’re genetically predisposed.

The problem is that Chavela is my aunt by marriage, so we don’t share a single gene. There goes another theory.

My second therapist told me that I “avoid intimacy with my weight,” implying that I subconsciously got fat to avoid being

touched. I know this theory is also bullshit, simply because I love being touched.

But my favorite explanation of why I’m fat is the most complicated and romantic of them all. I call it “the nanny theory,”

and it involves a crying mother, sharks, a military base, and sex out of wedlock.

Allow me to explain. My mother hired a nanny when I was just a baby. Our nanny was a teenage girl from a small town in Cuba.

Her name was Inocencia, but we called her “Ino.” She was young and naïve, she had never been in a big city like New York,

and, like any other lonely teen, she was looking to fall in love.

And she fell in love. Yes, she fell in love with pastries.

My friend Wilfredo’s aunt claimed that after menopause all her sensitivity left her genitals and went up to her mouth, making

her replace sex with food. I can imagine that something similar happened to Ino, but during her adolescence.

I can almost see her. The year was 1975, she had just turned sixteen, and was bursting with the nervous energy of a high-school

athlete about to compete in a cross-country marathon. The night was warm, but she was shivering as she gathered the courage

to jump in the waters at Caimanera Beach, determined to swim through the shark-infested Guantánamo Bay. Was she alone? Was

she with others on this suicidal attempt to reach the American base? I don’t know, but I can imagine her saying goodbye to

her teary-eyed mother. I can almost hear her mother warning her—not only against the hazards of her trip, but of an inevitable

danger, those blond and blue-eyed men who would—no doubt—knock her up and abandon her with her baby once she reached the United

States.

“¡Cuidado ¡con quedar preñada!” her mom probably said in a tone of voice that would haunt Ino forever.

What a great example of Cuban motherly logic: never mind the risk of drowning, getting shot by the Cuban military police,

or being eaten by a “great white.” The real danger here was that Ino could get pregnant out of wedlock once she reached American

soil. I have to say that, even though I might be suffering the consequences of Ino’s love affair with cinnamon rolls, I do

understand where she was coming from. Under such intense conditions, Ino must have made a secret promise to the Virgin of

Regla to never give up the flower of her virginity, and to remain celibate if she made it safe and sound to the United States.

My mother was the first one to hire Ino when she got to New York. She heard about her through what Cubans call Radio Bemba,

a sort of Cuban-emigrant broadcasting service that consisted of a bunch of Cuban housewives calling each other every day to

deliver news and gossip. Mom decided to hire Ino for two reasons: first, to help a fellow Cuban in need of a job; and, second,

because she badly needed a full-time maid/nanny at home. My father’s food-import business was going down. His partner had

stolen the company’s cash and moved to Florida, so Dad, on the verge of bankruptcy and too traumatized to trust anybody, asked

Mom to run the business with him.

Mom, understanding Dad’s desperate plea for support, was forced to work full-time in the Jersey City warehouse, keeping track

of shipments of yucca and plantains, while she trusted the care of her home, her three prepubescent sons, and her baby girl

to the sweet, young, innocent, virginal Ino.

Every week while employed by my mother, Ino would spend her complete salary on pastries. She would even bring some to our

home. My mother, who is certainly not the Mae West type, was so shocked by her oral fixation that she encouraged her to slow

down her sugar intake and go out on the weekend to someplace where she could meet boys. But Ino showed no interest in men,

romance, or sex. Just dessert.

One day, Mom had a minute to spare and joined Ino and me for my spoon-fed dinner. Mom decided to taste the oatmeal that Ino

had cooked for me, but as soon as it touched her lips she had to spit it out.

“¿Qué carajo le pusiste a la avena?”

“Un poquito de azúcar para que la niña la coma.”

The oatmeal had so much sugar that it was virtually inedible. Ino confessed then that, given the natural reluctance to eat

which most children show, she had been adding absurd quantities of sugar to all my meals, making me a tiny and plump sugar

addict and probably screwing my metabolism for life. Mom never told me if this incident got Ino fired or not, but Ino left

our lives very soon after that episode. I’ve noticed that Mom silently suffers every time I bring up Ino and “the nanny theory.”

Often I hope that my Cuban nanny ended up fat, knocked up, and abandoned by the same ruthless young male that her mother warned

her against.

Thanks to Ino, my first childhood memory is standing in front of a mirror and saying to my already overweight self, “I’m a

three-year-old girl and I’m about ten pounds heavier than I should be.” I’m twenty-eight years old now, and I’ve always been

fat—by a few pounds or a lot of them, since it kind of fluctuates. And I can proudly say that I owe it all to the sweet, stupid,

and innocent Ino.

I have never known what it is like not to be fat. I’m always trying to lose weight, or worried about getting even fatter than

I already am. My size has varied considerably through the years—sometimes within weeks, depending on how absurd the diet of

the moment was—but no matter what I do, the fat always comes back. Let’s see: I’ve tried the Scarsdale, the Atkins—the first

time around and the second time around—the anti-diet, homeopathic remedies, acupuncture. You name it and I’ve done it. If

it works, it’s only temporarily.

My mom took me to a dietician in the eighties who helped me lose weight incredibly fast with little effort on my part. It

was the infamous Dr. Loomis. He was so popular that the long line of patients spilled into the hallway outside his office.

But the line moved fast, because Dr. Loomis ran four examination rooms at the same time. He would spend an average of five

seconds with each patient. In that short time he’d manage to weigh you, make you stand naked in front of a mirror, and insult

you.

“Look at yourself,” he would say, contorting his face as if he were just about to puke, “look at those rolls of fat. Aren’t

you ashamed of yourself?”

This is what he called “encouragement.” Then he would give you a prescription for a powerful—and now illegal—drug whose long-term

side effects will become evident one day. Unfortunately, permanent weight loss wasn’t one of them. Eventually, Dr. Loomis

was incarcerated for giving speed to his patients.

But enough with the whining, and let’s deal with the reality: I’m fat. I have big boobs, a chunky butt, and thick legs. I

will say, in my defense, that my waist is kind of small, so at least I have an hourglass figure. Unfortunately, hourglasses

are not terribly popular nowadays.

The bottom line is that I’m fat. I’m a fat chick. We could come up with nicer ways to say it: plump, full-figured, overweight,

chubby. But after all these years of fatness, I finally feel good about saying it the simple way: fat. Just fat. If you happen

to be fat, I strongly recommend you to say it out loud at every opportunity you have. If “fat” is a word that defines you,

you should embrace it, and never give other people the power to use it as an insult. And now that we’re discussing linguistics,

I have to bring up another concern: my name.

Latinos have an odd tradition of giving weird names to their kids. Sometimes we combine the parents’ names. If they are, for

instance, Carlos and Teresa, they could name the baby girl Caresa. Other times we pick a word in a foreign language and slap

it on the newborn without thinking of the consequences.

There was a kid in school whose parents named him Magnificent. Yes, once I knew a Magnificent López. The only problem was

that Magnificent was short and skinny, and he wore thick eyeglasses. To be brutally honest, he looked anything but magnificent,

and his very name was a painful reminder of his shortcomings.

I have a similar problem. My name is Beauty.

Beauty María Zavala, to be precise.

I have three brothers who bear standard Latino names: Pedro, Francisco, and Eduardo. But in my case, my parents decided to

take a poetic license, and as a tribute to the land that saved them from Fidel Castro, they decided to name me Beauty. I’m

sure that at the time it sounded very cool to them, but you have no idea what a pain in the ass it is to drag this name along

with all my extra pounds.

For obvious reasons, I ask people to just call me B.

I’ve gone through life pushing this extra weight—that I simply can’t get rid of—and bearing a name that sounds like a bad

joke. It’s particularly annoying when I’m on the phone with my bank, or the credit-card company, and they ask me to spell

my name. I can’t blame them for being confused—let’s face it, there are not too many Beautys out there. But what really bothers

me is that every time I spell it out for them, I do it in the same stupid way:

“B as in ‘boy,’ E as in Edward…”

Why do I say “B as in ‘boy’”? I’m not a boy. Why can’t I just say “B as in ‘beauty’”? The answer is very simple: I have never

felt pretty. I’m fat, and I’ve grown up in a world where fat is anything but beautiful.

At this point I have to take a moment to acknowledge that there are other things in life that are much worse than being fat.

We can go through a whole list. I could be blind, deaf, paralyzed, starved, or brain-dead. The truth is that, in the category

of curses, fat is nothing more than chump change.

I strongly believe that the worst curse you can suffer in life is to be unhappy. I can tell you of many rich, beautiful, young,

healthy, and—of course—skinny people who have tried successfully and unsuccessfully to commit suicide out of pure, plain misery.

I’ve been sad, angry, and mortified about my weight, but, thank God, never suicidal.

But I’m bringing up the happiness factor because I’ve realized that it’s the one thing I could change. Let’s face it, I might

never be able to control my weight, but I’ve learned that I can choose to be happy. How did I learn?

You’ll soon find out.

I work in an ad agency in New York City. In case you don’t know it, let me tell you that New York is a bad city to be fat in.

Most people actually manage to stay thin, and I have no idea how.

If you go to any of the many fantastic restaurants in Manhattan, you’ll run into slender men and women who don’t seem affected

by sugars, carbohydrates, or partially hydrogenated oils. I honestly wonder if they’re all puking after every meal, or if

in fact they truly have an industrial boiler installed where I have my sluggish metabolism. These people are so thin—they

must burn everything they put in their mouths at the speed of light. Meanwhile, I store everything, in preparation—I guess—for

a nuclear holocaust.

I see the skinny ones on the street wearing designer clothes, or in the gym fighting some extra milligram of fat that I couldn’t

see with a microscope even if I tried. They sit comfortably in the bus or on the subway, in seats that are specially designed

for people of their size. They cross their legs in positions that I can only imagine. They wear jeans and leather pants, never

having to worry about wearing off the fabric between their thighs. I know, I know, I’m coming across a little obsessed with

the differences between them and me. I’m not always like this; I don’t see myself as an outsider all the time. The feeling

comes and goes with the seasons, or with the frustration caused by realizing that it’s time to go up one dress size. But in

spite of this rant, I’m not prejudiced against the skinny ones. Some of my best friends are very thin. As a matter of fact,

my best friend, Lillian, is particularly slender.

Lillian and I met at the ad agency on my first day at work. That morning I was very nervous, and I didn’t know anybody at

the office. Lillian came up to my desk and did one of the nicest things you could do to a rookie like me: she introduced herself,

and took me out to lunch. Even though we work for different departments—I’m a copywriter and she’s an accountant—we have been

inseparable ever since.

Lillian is Asian, tall, slender, with perfect boobs, a tight little ass, and—believe it or not—she is sweet, nice, and friendly.

She can be a little self-centered, a tad narcissistic, and a teeny bit insensitive, but the truth is that I love her to death.

Based on my experiences with my mother, I’ve come to believe that people who love you are bound to push your buttons, and

sometimes Lillian really knows how to push mine.

In any case, my story begins—sorry, it hasn’t started yet—on the morning of April 14, just a couple of years ago. I’m bad

with dates, but events that happened on Christmas Day, New Year’s Eve, or Valentine’s Day are always easier to remember. This

one happened on the day before taxes were due.

It was a nice spring morning. I was particularly proud of my hairdo that day. My hair is long and curly, and I usually wear

it in a tight bun because I think that makes me look skinnier and professional. I wear glasses—I’m a bit nearsighted, and

I should have contacts, but I’ve been so busy at work that I haven’t had a second to go to the eye doctor and get a new prescription.

I like my glasses, though, because they make me look professional, and I need to look professional as part of a long-delayed

plan to get ahead at my job. There’s this unwritten rule in corporate America that establishes that if you are not promoted

every two years, you are considered filler. I was two years overdue for that promotion, and I was starting to worry that if

I didn’t see any movement soon, I might never be anything in life other than a senior copywriter.

Let me explain what I do at the ad agency. I take a bunch of marketing information and I turn it into a paragraph, a slogan,

or a word. If they tell me, “We need to sell more peanuts to eighteen-year-olds,” then I find the words that make peanuts

irresistible to that demographic. Maybe you’ve heard of one of my masterpieces: “Gotta go nuts.” Yep, I came up with that

one, even though Bonnie, my boss, took the credit for it. But we’ll get back to Bonnie in a minute.

I like to think of myself as a poet who pays the rent writing infomercials, food labels, and even catalogue captions. I’m

aware that I’m not writing the great American novel here, but my job allows me to be fairly creative. I perform what I call

“art on demand.” I know we think that artists are not pressured by the needs of the market, but let me remind you that Leonardo

da Vinci didn’t paint the Mona Lisa because he wanted to. He did it because someone paid him to do it. Some rich guy in Florence probably told his wife, “Hey,

honey, maybe we should get someone to paint your portrait. Let me call that Leonardo guy.” That’s how Leonardo paid his rent.

In this respect all artists—or at least most artists who make a living with their craft—whore themselves out. You give us

cash and we sell our soul. What we should remember, though, is that we might be whores but we’re still artists. And making

art—or coming up with a slogan for a new brand of tampons, as I was doing at the time—is really hard when you’re not being

acknowledged.

In my agency, it didn’t matter if you were dumb as a rock, and you got the promotion by sleeping with your boss. As long as

you had your promotion every two years, you were well on your way to corporate success.

Sleeping with Bonnie was not an option, since she’s a woman—and not a pretty one, if you ask me. So I decided to take the

long road for that promotion: working hard.

I extra-busted my ass for years, trying to convince them that I deserved the title of creative director, but my efforts had

not paid off. The funny part is that I already had the job—what I was missing was the title. I’d been doing two jobs for the

last three years. When the last director left, they gave me her work responsibilities, but I continued doing mine as a senior

copywriter. So I was supervising a whole team of copywriters—like me—but I also had to write the ads, just like they did.

When the other creatives wrote their copy, they gave it to me. I reviewed it, corrected it, approved it, and then I passed

it on to Bonnie. But the absurd part of the whole arrangement was that when I wrote the copy for an ad, I, technically, had

to submit it to myself first—for review, correction, and approval—before I showed it to Bonnie. Does that make any sense?

I don’t think so. But that’s how big companies operate nowadays: they squeeze you for as many years as they can, “to see if

you are prepared for that promotion,” and then—once you’ve proved that you can do it—they go and hire someone else. The craziest

part is that, since you are the one who knows how to do it, they then expect you to train your new boss. Pretty fucked up,

huh?

But there was no point in entertaining those negative thoughts that morning, since I was convinced that that wasn’t going

to happen to me. I was determined to get that promotion, so for the last thirty-six months I had missed every meaningful family

gathering—important birthdays, major surgeries, and Christian holidays (which is a mortal sin in Cuban families). I made my

career my number-one priority. I was basically living in the office.

When they asked for a volunteer, I always raised my hand. When they asked for two ideas, I delivered twenty. I laughed out

loud at my boss’s bad jokes and asked about the health of dogs and cats that I didn’t give a rat’s ass about. I have felt

guilty about taking vacation time, and I have actually canceled anticipated trips because Bonnie forgot that she approved

my days off. I ate my lunch at my desk every day, carried a BlackBerry everywhere I went—including the bathroom—because it’s

a fact that Bonnie would call or e-mail me the moment I briefly removed my butt from my chair. Just to give you an idea of

how committed I was to my job, let me tell you that my doctor and my dentist mailed me notes wondering if I was dead, because

all my checkups were long overdue.

I became so dedicated that I was that person who went to work sick. If I was scolded for spreading the virus and I stayed

home to recover, then I was scolded for “getting sick too often.” I mastered the art of showing up sick at the office and

breathing as little as possible, to keep my germs to myself.

Determined as I was to move up, I patiently listened to every stupid idea that came from Bonnie’s mouth. I heard her dumbest

comments with respect and reverence. I even allowed her to walk all over me—something she seemed to particularly enjoy—just

to prove to her that I was there to support her and not to threaten her. I always made her look good, gave her credit when

she didn’t deserve it, and allowed her to present my work as if it were hers. I did it all to fulfill a simple dream: if I

got the position as creative director, I could use that to get a decent job in a different company, and free myself from Bonnie.

To give myself courage through this ordeal, I created a mantra that I repeated to myself over and over, every time I clashed

with her: “Hard work will set you free.” After a year of saying that every day, I read somewhere that this same phrase was

the slogan of the Nazi concentration camps, so I decided to switch to “one day at a time.” I was a prisoner in Bonnie’s camp,

but it couldn’t last forever.

How can I describe Bonnie? She’s skinny, wiry, with black—dyed—hair, reddish skin, and no lips. Physically, she is the Joan

Collins-at-sixty type. She’s the kind of person who, if you are entering a building and you hold the door for her, will walk

right through without saying thank you. She won’t even look at you, because she believes that God created all human beings

to serve her. As a matter of fact, I’ve never heard her utter the words “please” or “thank you.” She’s the kind of guest who

would wear white to a wedding and chew gum in a funeral. She just couldn’t care less. But enough of her for now. Let’s continue.

That particular morning in April was lovely. Spring was in the air, and I remember rushing to work wearing my navy-blue suit.

I had the exact same suit in four colors (when I find something that somehow fits me, I always buy a few of them, ’cause I

never know when I’ll find something that actually looks half decent on me again). Anyway, I was wearing the blue suit, and

I noticed that it felt a little tight. I started wondering—in a vague attempt to cover up for the possibility that maybe I

had gained some weight—if the dry cleaners had shrunk my clothes.

As I walked up Fifth Avenue toward Fifty-ninth Street, I tried to calculate how many calories I was burning with this short

but brisk walk. The streets of midtown Manhattan can be a nightmare when you’re a fat chick at rush hour. I wanted to run

but I was in high heels. I could not wear sneakers to work, because a creative director would never fall to that temptation.

Moving through the sea of people felt like speed-walking an obstacle course. To top it off, while I had to hurry to make it

to work at a decent time, I couldn’t walk too fast or I’d end up all sweaty.

I walked into my office building and smiled at the security guard, who—once again—ignored me. Let me just point out that smiling

and flirting are two very different things, and flirting with this guy was not in my agenda because:

a) I don’t particularly like him.

b) I’ve noticed that he’s missing a few front teeth.

c) It’s not like he even bothers to make eye contact with me, and eye contact is essential for flirting.

But, in any case, I smiled at him. I smiled at this idiot every morning, simply because it is my philosophy that if you see

someone regularly it makes sense to at least acknowledge him with a smile. It’s called “being polite.” But the son of a bitch—who

clearly doesn’t have any social graces—just looked . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...