- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

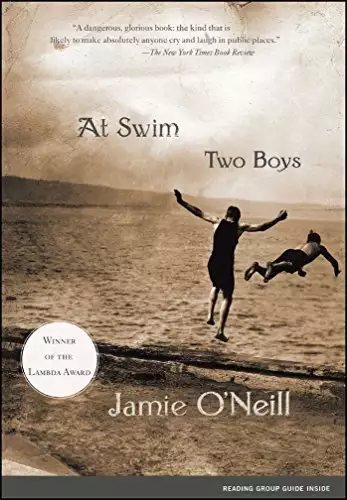

Praised as “a work of wild, vaulting ambition and achievement” by Entertainment Weekly, Jamie O’Neill’s first novel invites comparison to such literary greats as James Joyce, Samuel Beckett and Charles Dickens. Jim Mack is a naïve young scholar and the son of a foolish, aspiring shopkeeper. Doyler Doyle is the rough-diamond son—revolutionary and blasphemous—of Mr. Mack’s old army pal. Out at the Forty Foot, that great jut of rock where gentlemen bathe in the nude, the two boys make a pact: Doyler will teach Jim to swim, and in a year, on Easter of 1916, they will swim to the distant beacon of Muglins Rock and claim that island for themselves. All the while Mr. Mack, who has grand plans for a corner shop empire, remains unaware of the depth of the boys’ burgeoning friendship and of the changing landscape of a nation. Set during the year preceding the Easter Uprising of 1916—Ireland’s brave but fractured revolt against British rule— At Swim, Two Boys is a tender, tragic love story and a brilliant depiction of people caught in the tide of history. Powerful and artful, and ten years in the writing, it is a masterwork from Jamie O’Neill.

Release date: March 4, 2003

Publisher: Scribner

Print pages: 576

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

At Swim, Two Boys

Jamie O'Neill

At the corner of Adelaide Road, where the paving sparkled in the morning sun, Mr. Mack waited by the newspaper stand. A grand day it was, rare and fine. Puff-clouds sailed through a sky of blue. Fair-weather cumulus to give the correct designation: on account they cumulate, so Mr. Mack believed. High above the houses a seagull glinted, gliding on a breeze that carried from the sea. Wait now, was it cumulate or accumulate he meant? The breeze sniffed of salt and tide. Make a donkey of yourself, inwardly he cautioned, using words you don't know their meaning. And where's this paper chappie after getting to?

In delicate clutch an Irish Times he held. A thruppenny piece, waiting to pay, rolled in his fingers. Every so often his hand queried his elbow -- Parcel safe? Under me arm, his hand-pat assured him.

Glasthule, homy old parish, on the lip of Dublin Bay. You could see the bay, a wedge of it, between the walls of a lane, with Howth lying out beyond. The bay was blue as the sky, a tinge deeper, and curiously raised-looking when viewed dead on. The way the sea would be sloping to the land. If this paper chappie don't show up quick, bang goes his sale. Cheek of him leaving customers wait in the street.

A happy dosser was nosing along the lane and Mr. Mack watched with lenient disdain. Any old bone. Lick of something out of a can. Dog's life really. When he came to the street Mr. Mack touched a finger to his hat, but the happy dosser paid him no regard. He slouched along and Mr. Mack saw it puddling after, something he had spilt in the road, his wasted civility. Lips pursed with comment, he pulled, squeezing, one droop of his bush mustache.

"Oh hello, Mrs. Conway, grand day it is, grand to be sure, tip-top and yourself keeping dandy?"

Nice class of lady, left foot, but without the airs. Saw me waiting with an Irish Times, twice the price of any other paper. They remark such things, the quality do. Glory be, I hope she didn't think -- his Irish Times dropped by his side -- Would she ever have mistook me for the paperman, do you think?

Pages fluttered on the newspaper piles, newsboards creaked in the breeze. Out-of-the-way spot for a paper stand. Had supposed to be above by the railway station. But this thoolamawn has it currently, what does he do only creeps it down, little by little, till now he has it smack outside of Fennelly's --

Mr. Mack swivelled on his heels. Fennelly's public house. The corner doors were propped wide where the boy was mopping the steps. Late in the morning to be still at his steps. The gloom inside gave out a hum of amusement, low mouths of male companionship, gathered by the amber glow of the bar. Mr. Mack said Aha! with his eyes. He thrust his head inside the door, waved his paper in the dark. "'Scuse now, gents." He hadn't his hat back on his head before a roar of hilarity, erupting at the bar, hunted him away, likely to shove him back out in the street.

Well, by the holy. He gave a hard nod to the young bucko leaning on his mop and grinning. What was that about?

Presently, a jerky streak of anatomy distinguished itself in the door, coughing and spluttering while it came, and shielding its eyes from the sun. "Is it yourself, Sergeant?"

"Hello now, Mr. Doyle," said Mr. Mack.

"Quartermaster-Sergeant Mack, how are you, how's every hair's breadth of you, what cheer to see you so spry." A spit preceded him to the pavement. "You weren't kept waiting at all?" This rather in rebuttal than inquiry. "Only I was inside getting of bronze for silver. Paper is it?"

The hades you were, thought Mr. Mack, and the smell of drink something atrocious. "Fennelly has a crowd in," he remarked, "for the hour."

"Bagmen," the paperman replied. "Go-boys on the make out of Dublin. And a miselier mischaritable unChristianer crew -- "

Ho ho ho, thought Mr. Mack. On the cadge, if I know my man. Them boys inside was too nimble for him.

"Would you believe, Sergeant, they'd mock a man for the paper he'd read?"

"What's this now?" said Mr. Mack.

The paperman chucked his head. "God be their judge and a bitter one, say I. And your good self known for a decent skin with no more side than a margarine."

Mr. Mack could not engage but a rise was being took out of him. The paperman made play of settling his papers, huffling and humphing in that irritating consumptive way. He made play of banging his chest for air. He spat, coughing with the spittle, a powdery disgruntled cough -- "Choky today," said he -- and Mr. Mack viewed the spittle-drenched sheet he now held in his hand. This fellow, the curse of an old comrade, try anything to vex me.

"I'm after picking up," choosily he said, "an Irish Times, only I read here -- "

"An Irish Times, Sergeant? Carry me out and bury me decent, so you have and all. Aren't you swell away with the high-jinkers there?"

Mr. Mack plumped his face and a laugh, like a fruit, dropped from his mouth. "I wouldn't know about any high-jinkers," he confided. "Only I read here 'tis twice the price of any other paper. Twice the price," he repeated, shaking his cautious head. A carillon of coins chinkled in his pocket. "I don't know now can the expense be justified."

"Take a risk of it, Sergeant, and damn the begrudgers." The paperman leant privily forward. "A gent on the up, likes of yourself, isn't it worth it alone for the shocks and stares?"

Narrowly Mr. Mack considered his man. A fling or a fox-paw, he couldn't be certain sure. He clipped his coin on the paper-stack. "Penny, I believe," he said.

"Thruppence," returned Mr. Doyle. "Balance two dee to the General."

Mr. Mack talked small while he waited for his change. "Grand stretch of weather we're having."

"'Tisn't the worst."

"Grand I thought for the time of year."

"Thanks be to God."

"Oh thanks be to God entirely."

Mr. Mack's face faltered. Had ought to get my thanks in first. This fellow, not a mag to bless himself with, doing me down always. He watched him shambling through the pockets of his coat. And if it was change he was after in Fennelly's it was devilish cunning change for never the jingle of a coin let out. A smile fixed on Mr. Mack's face. Barking up the wrong tree with me, my merry old sweat. Two dee owed.

At last the paperman had the change found. Two lusterless pennies, he held them out, the old sort, with the old Queen's hair in a bun. Mr. Mack was on the blow of plucking them in his fingers when the paperman coughed -- "Squeeze me" -- coughed into his -- "Squeeze me peas, Sergeant" -- coughed into his sleeve. Not what you'd call coughing but hacking down the tracts of his throat to catch some breath had gone missing there. His virulence spattered the air between, and Mr. Mack thought how true what they say, take your life in your hands every breath you breathe.

He cleared his own throat and said, "I trust I find you well?"

"Amn't I standing, God be praised?" With a flump then he was down on the butter-box he kept for a seat.

Bulbous, pinkish, bush-mustached, Mr. Mack's face lowered. He'd heard it mentioned right enough, that old Doyle, he was none too gaudy this weather. Never had thought to find him this far gone. That box wouldn't know of him sitting on it. He looked down on the dull face, dull as any old copper, with the eyes behind that looked chancy back. Another fit came on, wretched to watch, like something physical had shook hold the man; and Mr. Mack reached his hand to his shoulder.

"Are you all right there, Mick?"

"Be right in a minute, Arthur. Catch me breath is all."

Mr. Mack gave a squeeze of his hand, feeling the bones beneath. "Will I inquire in Fennelly's after a drop of water?"

"I wouldn't want to be bothering Fennelly for water, though."

Them chancy old eyes. Once upon a time them eyes had danced. Bang goes sixpence, thought Mr. Mack, though it was a shilling piece he pulled out of his pocket. "Will you do yourself a favor, Mick, and get something decent for your dinner."

"Take that away," Mr. Doyle rebuked him. "I have my pride yet. I won't take pity."

"Now where's the pity in a bob, for God's sake?"

"I fought for Queen and Country. There's no man will deny it."

"There's no man wants to deny it."

"Twenty-five years with the Colors. I done me bit. I went me pound, God knows if I didn't."

Here we go, thought Mr. Mack.

"I stood me ground. I stood to them Bojers and all."

Here we go again.

"Admitted you wasn't there. Admitted you was home on the boat to Ireland. But you'll grant me this for an old soldier. That Fusilier Doyle, he done his bit. He stood up to them Bojers, he did."

"You did of course. You're a good Old Tough, 'tis known in the parish."

"Begod and I'd do it over was I let. God's oath on that. We'd know the better of Germany then." He kicked his boot against the newsboard, which told, unusually and misfortunately for his purpose, not of the war at all but of beer and whiskey news, the threat and fear of a hike in the excise. "I'd soon put manners on those Kaiser lads."

"No better man," Mr. Mack conceded. Mr. Doyle tossed his head, the way his point, being gained, he found it worthless for a gain. Mr. Mack had to squeeze the shilling bit into his hand. "You'll have a lotion on me whatever," he said, confidentially urging the matter.

The makings of a smile lurked across the paperman's face. "There was a day, Arthur, and you was pal o' me heart," said he, "me fond segotia." The silver got pocketed. "May your hand be stretched in friendship, Sergeant, and never your neck."

Charity done with and the price of a skite secured, they might risk a reasonable natter. "Tell us," said Mr. Mack, "is it true what happened the young fellow was here on this patch?"

"Sure carted away. The peelers nabbed him."

"A recruitment poster I heard."

"Above on the post office windows. Had it torn away."

"Shocking," said Mr. Mack. "Didn't he know that's a serious offense?"

"Be sure he'll know now," said Mr. Doyle. "Two-monthser he'll get out of that. Hard."

"And to look at him he only a child."

"Sure mild as ever on porridge smiled. Shocking."

Though Mr. Mack could not engage it was the offense was referred to and not the deserts. "Still, you've a good few weeks got out of this work."

"They'll have the replacement found soon enough."

"You stuck it this long, they might see their way to making you permanent."

"Not so, Sergeant. And the breath only in and out of me." An obliging little hack found its way up his throat. "There's only the one place I'll be permanent now. I won't be long getting there neither."

But Mr. Mack had heard sufficient of that song. "Sure we're none of us getting any the rosier." The parcel shifted under his arm and, the direction coming by chance into view, Mr. Doyle's eyes squinted, then saucered, then slyly he opined,

"Knitting."

"Stockings," Mr. Mack elaborated. "I'm only on my way to Ballygihen. Something for Madame MacMurrough and the Comforts Fund."

"Didn't I say you was up with the high-jinkers? Give 'em socks there, Sergeant, give 'em socks."

Mr. Mack received this recommendation with the soldierly good humor with which it was intended. He tipped his hat and the game old tough saluted.

"Good luck to the General."

"Take care now, Mr. Doyle."

Parcel safe and under his arm, Mr. Mack made his way along the parade of shops. At the tramstop he looked into Phillips's ironmongers. "Any sign of that delivery?"

"Expected" was all the answer he got.

Constable now. Sees me carrying the Irish Times. Respectable nod. Little Fenianeen in our midst and I never knew. After hacking at a recruitment poster. Mind, 'tis pranks not politics. Pass a law against khaki, you'd have them queueing up to enlist.

The shops ended and Glasthule Road took on a more dignified, prosperous air. With every step he counted the ratable values rising, ascending on a gradient equivalent to the road's rise to Ballygihen. Well-tended gardens and at every lane a kinder breeze off the sea. In the sun atop a wall a fat cat sat whose head followed wisely his progress.

General, he calls me. Jocular touch that. After the General Stores, of course. Shocks and stares -- should send that in the paper. Pay for items catchy like that. Or did I hear it before? Would want to be sure before committing to paper. Make a donkey of yourself else.

A scent drifted by that was utterly familiar yet unspeakably far away. He leant over a garden wall and there it blew, ferny-leaved and tiny-flowered, in its sunny yellow corner. Never had thought it would prosper here. Mum-mim-mom, begins with something mum. Butterfly floating over it, a pale white soul, first I've seen of the year.

Pall of his face back there. They do say they take on worse in the sunshine, your consumptives do. Segotia: is it some class of a flower? I never thought to inquire. Pal of me heart. Well, we're talking twenty thirty years back. Mick and Mack the paddy whacks. We had our day, 'tis true. Boys together and bugles together and bayonets in the ranks. Rang like bells, all we wanted was hanging. But there's no pals except you're equals. I learnt me that after I got my very first stripe.

He looked back down the road at the dwindling man with his lonely stand of papers. A Dublin tram came by. In the clattering of its wheels and its sparking trolley the years dizzied a moment. Scarlet and blue swirled in the dust, till there he stood, flush before him, in the light of bright and other days, the bugler boy was pal of his heart. My old segotia.

Parcel safe? Under me arm.

The paper unfolded in Mr. Mack's hands and his eyes glanced over the front page. Hotels, hotels, hotels. Hatches, matches, dispatches. Eye always drawn to "Loans by Post." Don't know for why. What's this the difference is between a stock and a share? Have to ask Jim when he gets in from school.

He turned the page. Here we go. Royal Dublin Fusiliers depot. Comforts Fund for the Troops in France. Committee gratefully acknowledges. Here we go. Madame MacMurrough, Ballygihen branch. Socks, woollen, three doz pair.

Gets her name in cosy enough. Madame MacMurrough. Once a month I fetch over the stockings, once a month she has her name in the paper. Handy enough if you can get it.

Nice to know they're delivered, all the same, delivered where they're wanted.

His eyes wandered to the Roll of Honor that ran along the paper's edge. Officers killed, officers wounded, wounded and missing, wounded believed prisoners, correction: officers killed. All officers. Column, column and a half of officers. Then there's only a handful of other ranks. Now that can't be right. How do they choose them? Do you have to -- is that what I'd have to do? -- submit the name yourself? And do they charge for that? Mind you, nice to have your name in the Irish Times. That's what I'll have to do maybe, should Gordie -- God forbid, what was he saying? God forbid, not anything happen to Gordie. Touch wood. Not wood, scapular. Where am I?

There, he'd missed his turn. That was foolish. Comes from borrowing trouble. And it was an extravagance in the first place to be purchasing an Irish Times. Penny for the paper, a bob for that drunk -- Jacobs! I didn't even get me two dee change. One and thruppenny walk in all. Might have waited for the Evening Mail and got me news for a ha'penny.

However, his name was Mr. Mack, and as everyone knew, or had ought know by now, the Macks was on the up.

The gates to Madame MacMurrough's were open and he peered up the avenue of straggling sycamores to the veiled face of Ballygihen House. A grand lady she was to be sure, though her trees, it had to be said, could do with a clipping.

He did not enter by the gates, but turned down Ballygihen Avenue beside. He had come out in a sweat, beads were trickling down the spine of his shirt, the wet patch stuck where his braces crossed. He mended his pace to catch his breath. At the door in the wall he stopped. Mopped his forehead and neck with his handkerchief, took off his hat and swabbed inside. Carefully stroked its brim where his fingers might have disturbed the nap. Replaced it. Size too small. Would never believe your head would grow. Or had the hat shrunk on him? Dunn's three-and-ninepenny bowler? No, his hat had never shrunk. He brushed both boots against the calves of his trousers. Parcel safe? Then he pushed inside the tradesmen's gate.

Brambly path through shadowy wood. Birds singing on all sides. Mess of nettles, cow-parsley, could take a scythe to them. Light green frilly leaves would put you in mind of, ahem, petticoats. A blackbird scuttled off the path like a schoolboy caught at a caper. Then he was out in the light, and the lawns of Ballygihen House stretched leisurely to the sea. The sea oh the sea, long may it be. What a magnificent house it was, view and vantage them both, for its windows commanded the breadth of Dublin Bay. If he had this house what wouldn't he do but sit upon its sloping lawns while all day long the mailboats to'd and fro'd.

Mr. Mack shook his head, but not disconsolately; for the beauty of the scene, briefly borrowed and duly returned, would brighten the sorrow of a saint. He followed the path by the trees, careful of stepping on the grass, till he came into the shadow of the house where the area steps led down to the kitchens.

And who was it only Madame MacMurrough's slavey showing leg at the step. Bit late in the morning to be still at her scrubbing. From Athlone, I believe, a district I know nothing about, save that it lies at the heart of Ireland.

He leant over the railing. "You're after missing a spot, Nancy."

The girl looked up. "'Tis you, Mr. Mack. And I thought it was the butcher's boy after giving me cheek."

She thought it was the butcher's -- Mr. Mack hawked his throat. "Julian weather we're having."

She pulled the hair out of her eyes. "Julian, Mr. Mack?"

"Julian. Pertaining to the month of July. It's from the Latin."

"But 'tis scarce May."

"Well, I know that, Nancy. I meant 'tis July-like weather. Warm."

She stood up, skirts covering her shins. Something masonic about her smile. "Any news from Gordie, Mr. Mack?"

Mr. Mack peered over her shoulder looking to see was there anyone of consequence about. "Gordie?" he repeated. "You must mean Gordon, my son Gordon."

"No letters or anything in the post?"

"How kind of you, Nancy. But no, he's away on final training. We don't know the where, we don't know the where to. Submarines, do you see. Troop movements is always secretive in times of war."

"Ah sure he's most like in England, round about Aldershot with the rest of the boys."

No cook in evidence, no proper maid. Entire residence has the look of -- "Aldershot? Why do you say Aldershot?"

"Do you know the place? Famous military town in Hampshire."

"You oughtn't be talking such things. Haven't I just warned you about submarines?"

"In Ballygihen, Mr. Mack?"

"Matter a damn where." He felt he had stamped his foot, so he patted his toes on the gravel and muttered, "Dang. Matter a dang, I meant."

The breeze reblew the hair in her eyes. Slovenly the way she ties it. Has a simper cute as a cat. "Is there no person in authority here I might address my business to?"

"Sure we're all alone in the big house together. If you wanted you could nip round the front and pull the bell. I'd let you in for the crack."

Flighty, divil-may-care minx of a slavey. Pity the man who -- He pinched, pulling, one droop of his mustache. "I haven't the time for your cod-acting now, Nancy. It so happens I'm here on a serious matter not altogether disconnected with the war effort itself. I don't doubt your mistress left word I was due."

She looked thoughtful a moment. "I misrecall your name being spoke, but there was mention of some fellow might be bringing socks. I was to dump them in the scullery and give him sixpence out of thank you."r

After the huffing and puffing and wagging his finger, in the end he had to let his parcel into her shiftless hands. She knew better by then to bring up the sixpence. He had tipped his scant farewell and was re-ascending the steps when she let out, "Still and all, Mr. Mack, it's the desperate shame you wouldn't know where your ownest son was stationed at."

"A shame we all must put up with."

"Sure wherever it is, he'll be cutting a fine dash of a thing, I wouldn't doubt it."

Slavey, he thought, proper name for a rough general. "Don't let me disturb you further from your duty."

"Good day, Mr. Mack. But remember now: all love does ever rightly show humanity our tenderness."

All love does what? Foolish gigglepot. Should have told her, should have said, he's gone to fight for King and Country and the rights of Catholic Belgium. Cutting a dash is for rakes and dandyprats. All love does ever what?

He sloped back down the road to Glasthule, his heart falling with the declining properties. Could that be true about the sixpence? It was a puzzle to know with rich folk. Maybe I might have held on to the stockings and fetched them over another day. Nothing like a face-to-face in getting to know the worth of a man. Or maybe the lady supposed I'd be too busy myself, would send a boy instead. Jim. She thought it was Jim I'd be sending. Jim, my son James. The sixpence was his consideration. Now that was mighty generous in Madame MacMurrough. Sixpence for that spit of a walk? There's the gentry for you now. That shows the quality.

Quick look-see in the hand-me-down window. Now that's new. Must tell Jim about that. A flute in Ducie's window. Second thoughts, steer clear. Trouble enough with Gordie and the pledge-shop.

Brewery men at Fennelly's. Mighty clatter they make. On purpose much of the time. Advertise their presence. Fine old Clydesdale eating at his bait-sack. They look after them well, give them that. Now here's a wonder -- paper stand deserted. Crowd of loafers holding up the corner.

A nipper-squeak across the road and his heart lifted for it was the boy out of the ironmonger's to say the tram had passed, package ready for collection. He took the delivery, signed the entry-book, patting the boy's head in lieu of gratuity, recrossed the street.

He was turning for home into Adelaide Road, named after -- who's this it's named for again? -- when Fennelly's corner doors burst open and a ree-raw jollity spilt out in the street. "Sister Susie's sewing shirts for soldiers," they were singing. Except in their particular rendition it was socks she was knitting.

"Quare fine day," said one of the loafers outside. Another had the neck to call out Mr. Mack's name.

Mr. Mack's forefinger lifted vaguely hatwards. Corner of his eye he saw others making mouths at him. Loafers, chancers, shapers. Where were the authorities at all that they wouldn't take them in charge? Fennelly had no license for singing. And the Angelus bell not rung.

Package safe? Under me arm. Chickens clucking in the yards, three dogs mooching. What they need do, you see, is raise the dog license. That would put a stop to all this mooching. Raise the excise while they're about it. Dung in the street and wisps of hay, sparrows everywhere in the quiet way.

The shop was on a corner of a lane that led to a row of humbler dwellings. He armed himself with a breath. The bell clinked when he pushed the door.

Incorrect to say a hush fell on the premises. They always spoke in whispers, Aunt Sawney and her guests. There she sat, behind the counter, Mrs. Tansy sat on the customers' chair, they had another fetched in from the kitchen for Mrs. Rourke. Now if a customer came, he'd be hard put to make it to the till. Gloomy too. Why wouldn't she leave the door wide? Gas only made it pokier in the daylight. Which was free.

"God bless all here." He touched the font on the jamb. Dryish. Have to see to that. Blessed himself.

"Hello, Aunt Sawney. Ready whenever to take over the reins. Mrs. Rourke, how's this the leg is today? I'm glad to see you about, Mrs. Tansy."

New tin of snuff on the counter. Must remember to mark that down in the book. Impossible to keep tabs else. Straits of Ballambangjan ahead. "I wonder if I might just...pardon me while I...if you could maybe." Maneuver safe between. Find harbor in the kitchen. Range stone cold, why wouldn't she keep an eye on it? Poke head back inside an instant. "Range is out, Aunt Sawney, should your guests require some tea."

Three snorts came in reply as each woman took a pinch of snuff.

He sat down at the kitchen table, laid the new package in front of him. His eyes gauged its contents, while he reached behind his neck to loosen the back-stud of his collar. He flexed his arms. Let me see, let me see. The boy at the ironmonger's had dangled the package by the twine and he had a deal of difficulty undoing the knot. Keep the torn paper for them on tick.

And finally there they were. Bills, two gross, finest American paper, fine as rashers of wind, in Canon bold proclaiming:

Adelaide General Stores

Quality Goods At Honest Prices

Mr. A. Mack, Esqr.

Will Be Pleased To Assist In All Your Requirements

An Appeal To You!

One Shilling Per Guinea Spent Here

Will Comfort Our Troops In France!

Page was a touch cramped at the base so that the end line, "Proprietress: Sawney Burke," had to be got in small print. Still, it was the motto that mattered, and that was a topper. Will comfort our troops in France. Appeal to the honor of the house.

Mustache. Touch it. Spot of something in the hairs. Egg, is it? Stuck.

Was I right all the same to leave it to honor only? Nothing about the pocket. How's about this for the hookum?

Pounds, Shillings and Pence!

Why Not Buy Local And Save On Leather?

Appeal to the pocket of the house. Might better have had two orders made up. One for the swells, other for the smells.

Never mind the smells, the Macks is on the up.

Jim. What time is it? Home for his dinner at five after one. Gone twelve now. He could maybe deliver the startings in his dinner-hour, the leavings before his tea.

Have I missed the Angelus so? How's this I missed the Angelus?

Clink. That's the door. Customer? No, exeunt two biddies. She'll be in now, tidy away. Aunt Sawney, I've had these advertising-bills made up...? No, wait till they're delivered first. Fate accomplished. Where's that apron? Better see to the range. "Aunt Sawney, there you are. Must be puffed out after that stint. I'll do shop now. You read the paper in your chair. We'll soon have a feel of heat."

"Stay away from that kitchener," she said.

"The range?" said Mr. Mack.

"That kitchener wants blacking."

"The range?"

She was already on her knees. She had a new tin of Zebra black-lead with her. "Ye'll have me hands in blisters. I left it go out since yesternight."

Surely a touch uncivil to name a kitchen range after the hero who avenged Khartoum. "Did we finish that other tin of Zebra already? Right so, I'll mark that down in the book. It's best to keep tabs."

"'Tis cold plate for dinner. And cold plate for tea."

"Whatever you think is best, Aunt Sawney. But you're not after forgetting it's his birthday today?"

"I'm not after forgetting this kitchener wants blacking." She damped a cloth in the black-lead tin, letting out a creak of coughing as she did so.

The door clinked. Customer. "I'll be with you directly," he called. Then, thoughtfully: "Not to trouble yourself, Aunt Sawney. I have a cake above out of Findlater's. Sure what more could his boyship want? But no mention of birthdays till after his tea. We'll have nothing brought off all day else."

"I suppose and you got him them bills for his treat."

Well, I'll be sugared. How would she know about the bills? He watched her at her labor for a moment. Wiry woman with hair the color of ash. The back tresses she wore in a small black cap which hung from her crown like an extra, maidenly, head of hair. Even kneeling she had a bend on her, what's this they used call it, the Grecian bends. If you straightened her now, you'd be feared of her snapping. Cheeks like loose gullets, wag when vexed. When the teeth go, you see, the pouches collapse. Nose beaked, with dewdrop suspending. Not kin, thanks be to God, not I, save through the altar. Gordie and Jim are blood.

She coughed again, sending reverberations down her frame. Brown titus she calls it. Useless to correct her at her age. "I'll leave the inside door pulled to in case you'd feel a chill from beyond. You're only over the bronchitis."

"Mrs. Tansy says the font wants filling."

Gently Mr. Mack reminded her, "Mrs. Tansy is a ranting Methody."

"She still has eyes to see."

Why would anyone look into a font? he wondered as he poured the holy water. Suppose when you are that way, dig with the other foot that is, these things take on an interest, a mystery even, which all too often for ourselves, digging as it were with the right foot, which is to say the proper one, have lost -- lost where I was heading for there.

<

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...