The dog days of August had arrived in Serenity, our sleepy little Iowa town nestled on the banks of the Mississippi River. Even at this early Thursday morning hour, inside our two-story stucco house with the air conditioner going full blast, I could tell it was going to be another hot and humid day.

At the moment, Mother and I were having breakfast in the dining room at the Duncan Phyfe table, with Sushi on the floor next to me, waiting for any bites that I might drop by accident or on purpose. Sushi’s idea of “dog days” is a 365-days-a-year proposition, in which heat and humidity are not a factor.

Mother is Vivian Borne, midseventies, Danish stock, her attractiveness hampered only slightly by large, out-of-fashion glasses that magnify her eyes; widowed, bipolar, and a legendary local thespian, she is even more legendary in our environs as an amateur sleuth.

I am Brandy Borne, thirty-three, blonde by choice, a Prozac-popping prodigal daughter who postdivorce (my bad) crawled home from Chicago to live with Mother, seeking solitude and relaxation but finding herself (which is to say myself) the frequent if reluctant accomplice in Vivian Borne’s mystery-solving escapades.

Sushi, whom you’ve already encountered, is my adorable diabetic shih tzu, whose diabetes-ravaged eyesight was restored by a cataract operation. Perhaps the smartest of our little trio, she is still taking daily insulin injections in trade for sugar-free treats.

For newbies just joining in—heaven help you. Life in Serenity isn’t always serene, nor is it uneventful, making catching you up in detail impractical. (Fortunately, all previous entries in these ongoing murder-mystery memoirs are in print.) Suffice to say, best fasten your seat belt low and tight and just come along for the ride. That’s what I do.

Longtime readers will recall that at the close of Antiques Wanted, Mother had been the only candidate left standing in the election for county sheriff, a race she won in a walk because it was too late for any last-minute competition. She won despite a write-in campaign launched by Serenity’s Millennials for John Oliver, the comedian/commentator of Last Week Tonight.

This irritated Mother no end. “He’s British,” she said again and again.

By the way, not revealing who I voted for is my constitutional right. I believe it’s called pleading the Fifth.

Mother’s breakfast today was a typically Spartan one—grapefruit juice and coffee. Mine wasn’t—pancakes with whipped cream and strawberries, bacon, orange juice, and coffee—but if ever a morning called for sugar rush, protein, vitamin C, and caffeine, this was it.

Between bites, I asked, “How’s the new communications system working?”

To my astonishment—and probably that of most townsfolk—Mother had kept her campaign promise to combine the separate dispatching systems of the police, sheriff, and fire departments into a single state-of-the art center to handle all three, making the routing of 911 calls to the appropriate responder quicker and more efficient.

And she had done this—as also promised—at no cost to the taxpayers. How? By relentlessly going after grants for law enforcement, and persuading—let’s not call it blackmail, shall we?—state representatives to assist her. These politicians knew that she knew they had skeletons in their closets they might not want to come rattling out. Okay, maybe call it blackmail . . . but implied blackmail.

Blackmail with a smile.

Mother, after taking a sip of coffee, replied, “The new com sys is strictly 10-2. Thank you for asking, dear!”

“Ten to what? What are you talking about?”

“10-2 is the police code for ‘signal good.’ You should familiarize yourself with all of them. I’ll provide a cheat sheet!”

She removed a napkin from her collar, as if she was the one chowing down like a lumberjack. Serenity’s new sheriff was dressed in a uniform of her own design, having tried on and rejected the scratchy, polyester ill-fitting one used by her predecessor, Pete Rudder. (To be clear, not the actual uniform he’d worn, but one supposedly in her size and for a female officer, though you’d never guess it.)

Anyway, Mother had contacted her favorite clothing company, Breckenridge, and—don’t ask me how—talked someone there into making several stylish jumpsuits of tan cotton/elastane with just the faintest hint of lavender, featuring plentiful pockets, epaulettes, and subtle shoulder pads. The outfits also had horizontal nylon zippers at the elbows and knees that turned them into a cooler (temp-wise) version when unzipped, which was how she was comfortably wearing one this steaming morning. (She still had the legs for it, and once a year she had any spider veins zapped.)

I said, “I’m surprised you followed through with it.”

Mother, about to take a sip of juice, frowned. “Followed through with what, dear?”

“The new communications center—especially one set up so that the public doesn’t have access to it.”

In the past, Mother had been able to walk into the PD and up to the Plexiglas, establish a rapport with the latest dispatcher, discover his or her weakness, then exploit those frailties to wheedle out confidential police information.

She gave me a smug little smile. “Well, dear, I’m on the inside now, and privy to everything.”

I grunted. When her term of office ended, Mother might well come to regret the upgrade. If she ran a second time, she would hardly be the only candidate for sheriff.

Her radio communicator, resting on the table, squawked, and she answered it.

“10-4, Deputy Chen,” she said.

Deputy Charles Chen was her right-hand man. I feel sure that Charles’s restaurateur parents were unaware of how close Chen was to Chan. Or maybe not—certainly nobody called the handsome young deputy Charlie.

“Businesses in Antiqua got broken into overnight.”

“A 10-14!”

“You want me to respond, Sheriff?”

“No, dear,” Mother told him. “And do please call me Vivian. And now I’m off to Antiqua! It’s time their mayor met the new county sheriff.”

“Okay.”

“I believe you mean 10-4, dear.”

The radio communicator clicked at her. She gave it a mildly offended look, then put it down, and—eyes gleaming behind the large lenses—announced, “Time for us to roll, Brandy!”

What did I have to do with rolling, you may ask?

Well, due to her various vehicular infractions—including but not limited to driving across a cornfield and knocking over a mailbox, both while off her medication—Sheriff Vivian Borne had no driver’s license . . . well, actually she did, it just had REVOKED stamped on it.

Since the department couldn’t spare a deputy just to haul her around, and the budget couldn’t afford the cost of an outside driver, she’d arm-twisted me into playing unpaid chauffeur.

And I wasn’t happy about it.

We’d had to temporarily close our antiques shop, Trash ’n’ Treasures—an old house where each room was devoted to antiques that thematically belonged there—but I guess that was okay, since August was always a slow month for sales, often more money going out than coming in. Still, schlepping Mother around town and countryside was not my idea of a summer vacation.

Sushi had also been pressed into service, riding along with us, partly because the little furball was so cute and disarming. She was bound to put most people at ease when the sheriff came a-callin’.

But Soosh could also be very vindictive when left home alone for long periods of time—more than once Mother and I had returned to find a small cigar left in the foyer.

Mother had a little jumpsuit made for her doggie deputy, as well, which got only one day’s wear before it was found shredded in the upstairs hallway, a mystery with no doubt as to who-done-it. I’d escaped any such indignity, my chauffeur’s uniform being my own sundresses and sandals.

I had made it clear to Mother that my role was to be strictly ex officio. I wanted no uniform or badge or official designation. Anyway, what could sound more ridiculous than “Deputy Brandy”?

While I cleared the table, Mother put on one of her two duty belts. She had a heavy one for serious situations, containing separate holders for her gun, nightstick, taser, handcuffs, mace, flashlight, and radio, plus pouches for bullets, Swiss Army knife, and latex gloves, and a lighter belt for investigations (like now), which included only holders for the radio, flashlight, and handcuffs, plus a large pouch for carrying antipsychotic pills, aspirin, antacids, allergy tablets, arthritis cream, eye drops, laxatives, lip balm, and dog treats to make canine friends. (She wanted to take all of her vitamins along as well, but the pouch wouldn’t close, and I purposely used a little cross-body purse so she couldn’t load me down.) She had as yet never worn her heavier rig with sidearm, as it ruined the line of her uniform.

I was exhausted already, and we hadn’t even left the house.

At a quarter to eight, Mother, Sushi, and I made the trek all the way outside and were immediately engulfed in oppressive heat. We trudged dutifully to her sheriff’s car parked in the driveway, doing our best not to wilt.

Mother had been given the choice of either a four-door Ford Taurus or a hatchback Ford Explorer. Both were white with sky-blue sheriff’s markings and the same policing equipment: in-car video system with monitor (mounted to the right of the rearview mirror), mobile data terminal (between the front seats and angled toward Mother), mobile radio system (beneath the dashboard), and standard steel mesh/Plexiglas barrier (between the front and back seats). There was also a bunch of hardware in the way-back, like a battering ram (not as easy to use as seen on TV), and a canvas bag carrying a gas mask, protective boots, extra flashlights, and other items.

Since I wasn’t an official law enforcement officer, I was prohibited from using any of this equipment, even if I knew how, which I didn’t. Nor did I have any desire to.

Being the designated driver, I had lobbied for the Taurus, feeling more comfortable behind its wheel. But Mother chose the Explorer, which I’d presumed was because the larger vehicle looked more formidable and had four-wheel drive. The real reason for her preference for the SUV had soon become apparent; yesterday, she spotted a rusty metal 1950s lawn chair by the roadside and commanded me to pull over and take custody of it, meaning put it in the hatchback.

Yes, folks, that’s what I’m dealing with. And who the good people of Serenity County have protecting them.

Anyway, with me behind the wheel, Sushi on Mother’s lap as the sheriff rode shotgun (not literally, though there was one in back), we headed out of Serenity—no siren wailing or lights flashing (that’s 10-85, according to my cheat sheet)—bound for Antiqua.

Our destination was not a Caribbean island but a little town located in the far western section of the county, just off Interstate 80, its sole industry the many antiques shops drawing tourists from all over the Midwest. Antiqua wasn’t large enough to have its own police force, contracting instead with the county sheriff’s department to provide certain services—like patrolling the area, investigating crimes, handling traffic, and offering crime prevention classes . . . every service provided at a cost, of course.

To stay awake after the heavy breakfast, I asked, “How come we’ve never gone to Antiqua looking for merchandise? Sounds like it would be right up the Trash ’n’ Treasures alley.”

We’d made any number of trips to little towns around the region on buying expeditions, starting back in the days when we had a stall in an antiques mall, prior to our shopkeeper phase.

“Because even with our dealer’s discount,” Mother said, “the prices are too high.”

When it came to hunting for bargains, Mother wasn’t just a bottom feeder, she was a subterranean gorger.

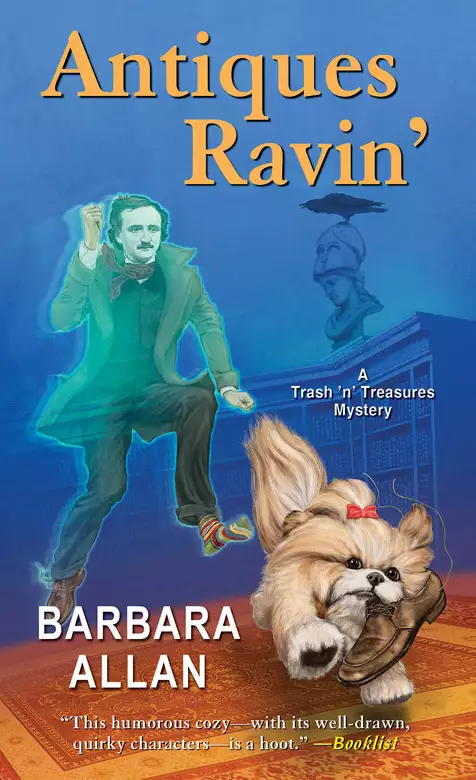

She went on: “Some of the shops in Antiqua used to be reasonable, and the occasional bargain could be sniffed out . . . but that was before Poe’s Folly.”

What do you think? Should I ask? Are you sure? Well . . . all right. But the responsibility is yours.

“What on earth,” I asked, “is Poe’s Folly?”

“Why, I’m surprised you’ve never heard of that, dear. It made news some years back. Quite a kerfuffle!”

I guess I’d been preoccupied with my own folly back in Chicago.

“One of the antique shops,” she continued, “sold a small framed photo to a tourist for ninety dollars.”

“That sounds a little high, but not the makings of anything newsworthy.”

Mother lifted a finger. “Actually, it was a newsworthy bargain—a daguerreotype dating to 1850 that turned out to be a rare portrait of Edgar Allan Poe himself. The store was crammed with so much stuff, the owners apparently didn’t know what they had.”

“So it was worth more than ninety dollars?”

“How about fifty-thousand simoleons.”

“Ouch!”

Mother continued, “Needless to say, the incident—indeed dubbed ‘Poe’s Folly’ by the media—was quite an embarrassment to the town, especially since the buyer took the picture to a taping of Antiques Roadshow in Des Moines, where the Antiqua shop’s costly blunder was exposed to eight and a half million viewers.”

I smirked. “Must’ve been pretty embarrassing to the person who sold it. Of course, it might encourage bargain hunters to drop by his shop.”

“One might think. But in fact it only called into question the shop owner’s ability to price anything correctly. He took it quite hard.”

“I thought any publicity was good publicity.”

“Apparently not, dear. The man killed himself.” She went on cheerfully, death never anything that brought her down. “Anyhoo, after the Folly became so widely known, prices skyrocketed all over town. No one wanted to make the same mistake twice!”

“Understandable,” I said, “but probably not good for business.”

She fluttered a hand. “Oh, initially it had no effect, because bargain hunters came from hither and yon. But when nothing of significance was discovered beyond outrageous price tags, tourism dropped off significantly.” She paused. “Then a few years back, the town council concocted a plan to turn their folly into fortune.”

“How’d they do that?” We were zipping along the Interstate now, despite truck-heavy traffic.

“The first weekend in August, Antiqua holds ‘Edgar Allan Poe Days,’ a gala three-day celebration with festivities beginning on Friday.”

“Well, that’s tomorrow,” I pointed out.

“Yes, and the pièce de résistance is a hunt for an authentic Poe collectible marked at a ridiculously low price.”

“Like that daguerreotype photo?”

“Nothing quite so valuable, dear, but still worth a pretty penny. An ingenious gimmick to embrace its famous folly, don’t you think?”

“Yes, but it must be tough coming up with Poe items like that.”

“Not really. Everyone on the town council is an antiques dealer with beaucoup connections. Last year’s treasure was a short missive Eddie Poe had written to a friend about a change of address, worth several thousand . . . priced at a mere twenty-five dollars.”

“Not too shabby,” I said. “How come we’ve never attended?”

Mother sniffed. “Because, dear, the first year the festival was held I wrote to the city council and offered to perform ‘The Raven’ at the opening ceremony, in full costume and makeup!”

“As what, a raven?”

“Don’t be ridiculous, dear! As Poe, of course. I look rather dashing in a mustache. And can you imagine? I never heard boo back from them!” She was getting miffed about it all over again, enough so to get a curious upward look from Soosh. “Well, I swore to myself I would darken Antiqua’s door, nevermore!”

“But now you’re sheriff and you have to.”

“And now they will see just who it was they snubbed!”

She didn’t just hold a grudge, she caressed it, nurtured it . . .

Fairly familiar with Poe’s work, I said, “Maybe the issue was what a long poem ‘The Raven’ is. Maybe if you had offered up a shorter one, like ‘Annabel Lee’ or ‘The City in the Sea’ . . .”

But she was snoring.

Serenity County’s new sheriff was starting her day off with a nap, as was the out-of-uniform deputy Sushi, curled in her lap.

The lady sleeps! Oh, may her sleep, which is enduring, so be deep!

I returned my attention to the road, where the gently rolling hills had been replaced with flat farmland, fields of tall green corn swaying seductively in the breeze, tassels ready for pollination.

Half an hour later, an exit sign to Antiqua appeared and I turned off the Interstate onto a secondary road, where a two-pump gas station kept company with a cut-rate motel.

Soon a larger sign greeted me:

The asphalt highway became cobblestone Antiques Drive, where well-kept houses on either side—newer ones on the outskirts, older but grander homes more centrally located—wore well-tended lawns in civic pride.

I passed a tree-shaded park with a large pond, several log-cabin-style picnic shelters, and a perfunctory playground, all deserted at this early hour. As I breezed on in to the small downtown, Mother and Sushi snored on.

I slowed the Explorer along the main drag to rubberneck at the quaint Victorian brick buildings decorated with colorful . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved