- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

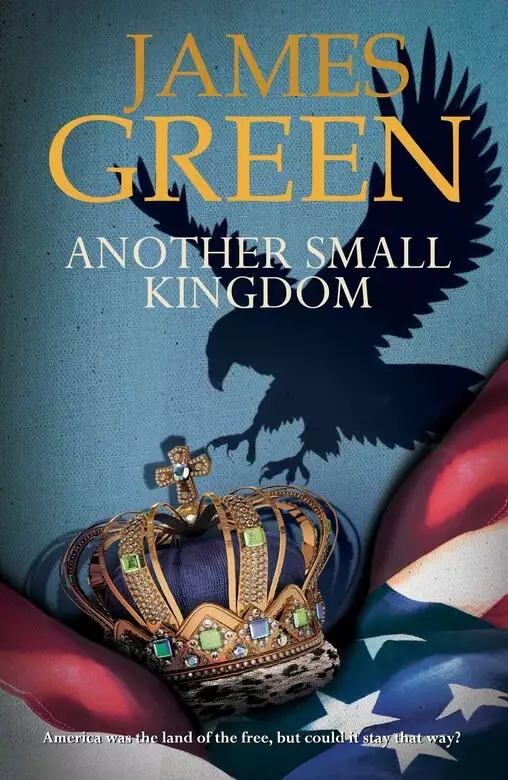

Synopsis

Boston, 1802, Lawyer Macleod is a man full of hate, a dangerous man. When a newly arrived young lawyer is mad enough to insult him, the consequences spin out of control and Macleod is caught up in a web of danger and intrigue. With England at war with France, some powerful Americans feel that theUSA?s best chance of remaining independent is to throw in their lot withFrance? even if it means accepting a French king ? for a while. To counter their plot, Macleod is sent toNew Orleans, where he meets Marie, wife of Etienne de Valois, aristocrat and fop, and through her learns a terrible secret. Together, unable to trust anyone, they race to uncover the traitors at the heart of the American Government. James Green uses fictional characters to illuminate the real events that lead to the birth of the American Intelligence Services and culminated in the extraordinary Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the USA ? at the cost of 3 cents an acre. Packed with action and fascinating historical detail, Another Small Kingdom will appeal both to those interested in the history of the USA and to aficionados of intelligent spy thrillers

Release date: October 11, 2012

Publisher: Accent Press

Print pages: 361

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Another Small Kingdom

James Green

PARIS 1802

February 23rd

The Office of Maurice de Talleyrand, Foreign Minister to the French Republic.

Ambassador Livingston was trying very hard to keep the hate from his eyes and the anger from his voice. Had he been able, like Samson, to bring the Tuileries Palace down on himself, but more especially on the head of the man sitting opposite him, he would have done so willingly.

‘Monsieur Talleyrand, if the American Republic is to expand, and it must expand …’

‘Grow or die, eh, Monsieur Ambassador? How very Napoleonic.’

‘There is no question of America dying, that is never going to happen. Ask the British if you doubt it.’

‘Of course I do not doubt it. But there is a question over whether it will grow, is there not?’

‘No, there is not. America will grow and will take its rightful place among the nations of the world.’

‘And that place will be?’

‘At any table where decisions are made which might affect America.’

‘So, America will be here, there and everywhere for, as we know, all decisions great or small affect all other decisions in some way or another. When the wine growers meet to discuss the vintage, America will be there. When farmers meet to discuss the harvest, America will be there. When the mistress of the house meets with the cook to discuss the menus for the week, America will be there. Very well. But tell me, Monsieur Ambassador Livingston, how many Americans do you think will be left in America while so many are away sitting at all these tables where decisions are made?’

‘Monsieur Foreign Secretary, you may choose to make a joke of my words if it pleases you to do so. But I know you understand my meaning. The fact that you play with the issue instead of discussing it shows you understand it very well indeed, and understand its importance. Make something look ridiculous and no one will take it seriously. Perhaps that works well enough with smaller issues but it will not work with this one, Monsieur Talleyrand, and no amount of wit nor clever words will make it otherwise. America will expand and America will sit at the Council Tables where the great nations meet.’

‘Monsieur Livingston, if you as the Ambassador of President Jefferson say that it will be so, then I am sure it will be as you say. One day, I am sure, America will be great in all senses of the word. The question I ask is, when will that day be?’

‘America will expand, Talleyrand, and it will be sooner rather than later.’

‘Ah, then you have come to some arrangement with the British?’

‘The British?’

‘Well, America cannot expand to the east unless American statesmen can build on water as well as walk on it. The same applies to the south, the Caribbean is just as wet as the Atlantic. That leaves north and that is British? Strange, I am usually so well informed and yet I have heard nothing of your negotiations with the British whereby you will move into their territories and they will move out.’

‘West, sir, west. America will expand across the Mississippi and into the Louisiana Territories. You know very well that is our intention because I have told you often enough that I am empowered by President Jefferson to negotiate for the purchase of those Territories.’

‘Ah, the American dream of going west, of course. How very remiss of me to have let it slip from my mind. But if your Government wishes to push west with its borders, surely you should be in Madrid? The Louisiana Territories, as everyone knows, are Spanish.’

‘The Louisiana Territories, as everyone knows, were negotiated back into French hands two years ago under the Treaty of San Ildefonso.’

‘But my dear sir, I know of no such treaty.’

‘The Secret Treaty of Ildefonso then, if you still prefer to play games.’

‘Ah, the Secret Treaty of Ildefonso, of course.’

‘Then if we both know that the Territories are French, we can discuss an American purchase and put these games to one side.’

‘I assure you, my dear Monsieur Ambassador, this is no game. It is deadly serious. If I discuss the sale of these Territories with you, I acknowledge the Treaty of San Ildefonso to a third party and it becomes no longer secret. I would have broken the terms of the treaty and Spain would have the right to re-claim the Territories.’

The French Republic’s Foreign Secretary spread his hands in that universal Gallic gesture which signifies, alas, what can one do?

Robert Livingston stood up angrily and paced the large and elegant room bringing his temper under control while Talleyrand sat back and watched him. Not for the first time the American Ambassador felt that the frustrations inherent in negotiating with this man were wearing him down to the point of despair. After a pause the gentle but almost mocking voice of Talleyrand resumed.

‘Perhaps there might be a way.’ Livingston turned. Could this be the first hint of negotiations actually beginning? He returned and stood at the desk. ‘If America were prepared to leave the matter secret. You would, of course, pay France the full purchase price on the signing of a Secret Treaty, but then do nothing until Spain was satisfied that any publication of the new nationality of the Louisiana Territories did not adversely affect Spanish interests. If and when Spain was satisfied, France would then be free to judge how French interests should be protected. Of course if, while Spain and France considered their positions, America did anything to prejudice the terms of the Treaty, perhaps negotiate with some other government and thereby give them knowledge of the Secret Treaty, the Territories would revert to France. More accurately, because of the Secret Treaty of San Ildefonso, they would appear to revert to Spain because France would, of course, keep the terms of the Secret Treaty of San Ildefonso and not make the true nationality of the Territories known to any other party. For if France did that the Territories would revert to Spain whose Territories they appear to be to all those not party to …’

But Robert Livingston was no longer present to appreciate the culmination of the Foreign Minister’s erudite exposition on the nature of Secret Treaties. The sound of his angry boots on the marble floor of the corridor rang out as he stormed away. A door in the corner of the fine office opened, Talleyrand’s secretary entered and waited until the sound of boots on marble died away. He then crossed the room and stood by the large elaborate desk.

‘It sounds as if it went well, Your Excellency?’

‘Well enough for the time being.’

‘You are too much for them, they lack flair, élan, subtlety …’

‘You have studied our American friends closely?’

The secretary made a contemptuous gesture.

‘Enough to know they are a country with thirty-two religions and only one sauce.’

Talleyrand laughed loudly.

‘Very drôle. But eventually I will have to deal with our Americans friends and, one way or another, I think they will force my hand. Livingston is no great diplomat but neither is he a fool however much I make him feel like one. One day America will send someone who will make me listen,’he paused,‘unless of course the plan of our very clever Minister of Police, Monsieur Fouché, is successful. If that happens then they will find they have other, far more important things to worry them and perhaps forget for a time their dream of going west.’

Chapter Two

That Lawyer Macleod was a man full of hate did not make him exceptional. What did make him exceptional was the completeness of his hate, and its great depth.

Macleod raised his eyes from the article in The Boston Commercial Gazette which lay over the contract papers on which he had been working. A man of middling age he wore a linen neck-cloth and a close-buttoned black coat. A man who despised display, his manner of dress was severely plain as was his view on the European war. If Europe was bent on self-destruction, then good luck to it. As far as he was concerned they could all go to hell in a wheelbarrow, led there by the strutting Little Corsican or Mad Farmer George. They could all dance to their graves to the music of musket-shot and cannon-fire. The French, the Prussians, the Austrians, the whole damned lot, men, women and children. Especially the damned British. In fact most of all the damned British.

He got up from his desk and went to the office window which was shut tight, his only concession to the late February weather. Down in the busy, wet street carriages and carts jostled and splashed. Crowds, wrapped in cloaks against the weather, hurried through the rain that carried with it flecks of snow with the promise of more to come. He looked at them for a moment. These were the people for whom he had fought in the late war, fought that they might be free and America independent. He had shed his blood for them. They were Americans, fellow citizens of the great new Republic. He would fight again for them if called on, yes, and die for them if necessary. But he could not feel for them. He did not wish to know their ambitions or aspirations, their sorrows, griefs or joys. To Lawyer Macleod they were a charge on his duty, a duty he owed to his country. They could never be an object for any personal emotion, because the only emotion left to Lawyer Macleod was hate. And that, of course, brought him back to the British.

Macleod left the window and returned to his desk where he put thoughts of the late war from him. That was ancient history, something gone with youth and joy. As for foreign wars and the politics of war, they were nothing to him unless they threatened his country. But the soldier in Lawyer Macleod, though dormant, was not dead. He began to muse for a moment on Napoleon, his military achievements and his likely ambitions.

He had sometimes said to clients that in his opinion Napoleon would prove to be more interested in France as a kingdom, his own kingdom, than in spreading the ideals of Revolution and Republic across Europe.

‘Mark my words,’ he would say when business was concluded, ‘Louis won’t be the last king of France. The Corsican will be given the Crown when he asks for it. And he will ask for it when there is no one left with the courage or power to deny it to him.’ And the client would nod and listen, and Lawyer Macleod would continue. ‘America is the only proper home for a republic. The true Free Man exists only in America and can exist only in America. Everywhere else it is master and slave, aristocrat and serf, ruler and ruled. Europe can no more cope with the idea of republican liberty than it could with religious liberty. That’s why Europe is dying while America is being born.’

It was an amazingly long speech by Lawyer Macleod’s standards and his clients, somewhat surprised at such loquacity, were happy to agree with him when he had said his piece. He was deep, was Lawyer Macleod, and he knew his business better than most. If, once in a while, he chose to speak on some subject outside the law, well it was probably best to listen and, having listened, take your leave.

Lawyer Macleod gave up his thoughts and pulled out his watch. It was time for lunch. He went to the door of his office, opened it and called out, ‘Lunch if you please, and make it now.’

There was the sound of someone jumping off a high stool in the outer office as the lawyer returned to his desk. An elderly clerk came in with a plain wooden tray bearing a coffee pot, cup and saucer, and a few dry biscuits. The clerk pushed the papers to one side, put the tray on the desk, then left closing the door behind him. As the coffee was steaming hot it was clear that the lunch had been ready to the minute, and that the clerk could have brought it in at the correct time without any command from the lawyer. But both lawyer and clerk were men of fixed habits, and men of fixed habits dislike change. For some years now the lawyer had opened the door at the same time each day and made the same peremptory command, at which the clerk had brought in the same lunch. No comment had ever passed nor was it likely that any comment ever would. The world of Lawyer Macleod’s office had little or no variety and was universally regarded by his clients as dull as the eye of a dead fish – and the elderly clerk honoured him for it.

Chapter Three

If the lawyer’s idea of luncheon was to read his paper, drink coffee and eat dry biscuits, there were those among his clients who took luncheon more seriously. They repaired, with others, to the select and popular Gallows Tree Club. The club’s grim name belied its grandeur both outside and inside, but referred to Boston Common which stood opposite across Beacon Street. It was on that Common that in 1656 Ann Hibbins, a wealthy widow, had been hanged on an oak tree for witchcraft, one of three women executed for the same crime. The club’s name was a tribute to the fact that the Boston witch trials pre-dated those of Salem by more than thirty years, a reminder if one was needed, that in all things of consequence Boston should regard itself as leader and guide.

In a well-appointed assembly room, after an excellent meal, a group of Boston’s best and brightest gathered for coffee, cigars and serious conversation.

Here the talk could not be of fashion or the other frivolous matters more suited to the mixed company of the dinner table. Here the talk could be only of business, the state of America and the state of the world.

Macleod’s last client of the morning was one of those who lunched at the club and was now sitting comfortably with coffee at his elbow and pulling on a good cigar. His fellow members listened as he told them that, while Macleod was an excellent Business and Contract lawyer, none better indeed, unfortunately he knew as much about politics as a dog knew about salvation. Heads nodded wisely in agreement. One of the older men commented that Lawyer Macleod took after his late father, a good man of business but a poor judge of life where its larger considerations were concerned. Another agreed. Yes, he most surely took after his father in that respect.

‘Euan Macleod. Now there was a dour Scot if ever there was one.’

‘It may be he takes after Euan in some ways,’ offered another, ‘but he certainly got his looks from his mother. Old Macleod was no picture but his son is a fine handsome man. He could have married again a dozen times over since the war on his looks alone.’

‘And picked up a tidy fortune with some of the young ladies who would have been pleased to have him as a husband. Many a mamma would have been happy for her daughter to become the second Mrs Macleod.’

‘Yes sir,’ remembered a stout, bald gentleman who had long since published a substantial second edition of his chin, ‘his mother was a fine woman indeed. I remember when I first saw her just after they had arrived over from Edinburgh.’ And he was once again, in his mind if no longer in reality, a dashing young buck twirling his killing, black mustachios. ‘Dam’me, gentlemen, on my life she was the prettiest thing that ever set foot in Boston.’

The older heads nodded in agreement and there was a brief pause of pleasant thoughts among the senior men. The mood was rudely interrupted by a man too young to be able to share any memories of the beautiful young Mrs Macleod.

‘Stap me, gentlemen, so it was the old story, eh, beauty and the beast? She had the looks and old Macleod had the tin? Blast my idleness, it’ll have to be the other way about with me, that’s for sure.’

The stout gentleman spoke coldly,

‘Not at all, Rayburn. The money was on her side as well as the beauty. What he brought to the match was brains, and fine brains at that. Euan Macleod may have had a face like a hoof-print in a cow pat, but there was nothing wrong with his business head. That man could make money out of fresh air and floor sweepings. He could see a good prospect at night, in a fog with a bag over his head. He was a fine man of business and died rich enough for plenty of good Boston Protestants to attend a Papist funeral.’

‘Aye, aye. True enough. A fine man, though, as you say, a Papist through and through.’

Heads nodded and the talk threatened to turn to religion when a new voice cut in with a lazy drawl which was almost a sneer.

‘So, Macleod’s got his father’s brains, his mother’s looks, plenty of family brass and is now in a good way of business in his own right. Pity he doesn’t seem to know how to enjoy any of it. For all the fun he seems to get out of life he might as well be a backwoods parson. God knows he seems satisfied to dress like one,’ and several of the younger men there grinned and sniggered in agreement.

Darcy was a young lawyer, in Boston only a year but well-to-do and dressed as near to the height of fashion as was possible. He spoke too loudly and too often for some of the older men but the younger set seemed to think something of him.

‘True enough, Darcy,’ agreed the self-confessed idler, Rayburn, ‘he’s a dull dog and dresses no better than his clerk, but I wish I had half the damned fellow’s luck.’

‘Some may choose to think Macleod a lucky man,’ drawled the young lawyer, ‘although I’d say you judge the luck of a man by the number and quality of his friends rather than the size of his house or the money in his pocket. Lawyer Macleod, it seems to me, has precious few friends of any sort. Does anyone see him in society? Does he dine? God’s teeth, gentlemen, look at yourselves. You never refer to him by any of his given names. In fact, I’ve been a year in Boston and I still don’t know what his given names are. No one uses them. He’s either Lawyer Macleod or plain Macleod.’ He paused, looked around, then smiled nastily. ‘But I do confess I have heard he is the possessor of a very unusual nickname, although with such a dry stick as Macleod I can’t imagine how he came by it. I was told he used to be called …’

One of the older men cut sharply across his words.

‘You would do well to keep any tittle-tattle of that sort to yourself, Darcy.’

The atmosphere in the room suddenly became charged.

‘What’s so damn serious about a nickname, and such a funny one at that? I didn’t make it up, although I must say it made me laugh,’ and indeed he did laugh. ‘How anyone like Macleod could pick up such a name as …’

But Darcy was again cut short.

‘I know of only two men who thought that nickname suitable for public laughter at Macleod’s expense. I’ll introduce them to you if you like, they’re not so far away. After meeting Macleod they decided to take up permanent residence very near here. I can take you to them both if you wish, they’re not far, just across the Common in the Burying Ground, and for all I know they’re still grinning at his nickname. But each one has a pistol ball in his head to remind him of what he’s grinning at.’

Another drove the point home.

‘In the head mind you, Darcy, not in the body.’

The older men, a few of whom had served with Macleod, nodded.

‘Macleod was one of the best pistol shots in the army in his day. If his eyes haven’t gone I still wouldn’t want to be on the business end of any pistol he was holding.’

The atmosphere changed again, still charged, but for another reason. The gathering listened as a new topic opened up.

‘But are his eyes still sharp, that’s the question? It’s some time since Macleod called anyone out.’

The gentleman with the chins smiled and looked around the assembly.

‘You know, it would be a fine thing to see if Macleod can still shoot straight. Yes sir, a fine thing.’

There was a pause before another voice added,

‘And a finer thing to wager on.’

An excited stir ran through the gathering.

‘By God, that would surely be something.’

‘I guess plenty of money would get put down on whether or not Macleod can still put a ball in a man’s head clean as a whistle. It would be a neat judgement either way.’

Murmurs of agreement met this profound sporting observation.

‘Yes sir, a fine thing.’

There was another pause while the best business brains of Boston began to consider if such an event might be brought off. Their deliberations were interrupted by a thoughtful sportsman who put his finger on the one weak spot in the proposed entertainment.

‘Except for the man Macleod called out, I guess.’

The room filled with laughter at this all too true observation, and suddenly all eyes were looking at Darcy. The young lawyer shifted uneasily and remained silent. He tried, without success, to look defiant. Before this afternoon he had merely disliked and despised lawyer Macleod. Now he found he hated him. After a short pause it became clear Darcy was unwilling to consider providing his friends with their entertainment or the prospect of making serious wagers. Someone cleared his throat and noisily took up a newspaper as a sign of change of subject.

‘More trouble down in New Orleans, I see. Those roughneck frontiersmen are making a nuisance of themselves again. Mark my words, that Spanish Governor Salcedo will do something about it soon. He won’t put up with it much longer.’ Heads nodded. ‘And when he does do something I can guess who he’ll do it to.’

A senior member of the post-luncheon gathering who had sat silent during the gay repartee, not being of a frivolous nature, harrumphed loudly. This signal being given, a polite silence fell. They acknowledged that the time had come for the serious-minded member to hold forth on his favourite topic, the failure of the Government to support, promote, or protect the interests of business and businessmen. Businessmen were, when all was said and done, at the heart of the economy and therefore the backbone of the nation.

‘Gentlemen.’ He paused to look about him to be sure he had the floor free of any possible interruption. ‘We all know the Mississippi is our main highway.’ Nods and murmurs of agreement. ‘And we also know that if Governor Salcedo squeezes us in New Orleans then we’re in trouble, gentlemen, big trouble.’ Hmms, ahs, and yes indeeds. The serious-minded member, feeling he had sufficiently conquered his audience with his opening salvo, settled down for a long occupation. ‘Without tax-free warehousing in New Orleans how is the South to get its exports on to European-bound merchantmen at a price that would turn a profit? Once forced to pay taxes for warehousing in New Orleans, gentlemen, what we get is not profit but loss. Yes sir, loss.’ Suppressed murmurs of agreement with at least two stifled yawns as the serious-minded member began to hit his stride. ‘Why, if that damned Spaniard taxes our storage facilities we might as well shut up shop. And mark my words, it’s our tax privileges Salcedo will have his eyes on. He’ll use these roughnecks, real or imaginary, to get them. Yes, gentlemen, I think I speak for all of us, indeed for all honest businessmen up and down the Mississippi, when I say …’

Sadly the gathering was denied the wisdom of what he, on behalf of all honest businessmen up and down the Mississippi, was about to say because his throat, drying from sudden oratory, commenced a coughing fit. Port wine was poured and handed to him. But as he drank the tide of comment flowed away from his shores and conversation became general.

‘Why don’t the Government do something, damn them? What good are they sitting in their fine new capital, Washington? They talk a great deal, I dare say …’

‘And what they talk about is more of their new taxes …’

‘They push plenty of paper around but they do damn little.’

‘And well paid to do that damn little by new taxes on our trade.’

‘But when it comes to looking after that trade and protecting trade from foreigners, we hear little enough. As for action we see nothing, gentlemen, not a damn thing.’

‘Haven’t they got the wit to control a few roughnecks? Isn’t trade bad enough with the war in Europe? But I guess you’re right, trade isn’t important to them, only taxes and politics, their eternal damn politics.’

‘Gentlemen,’ the serious-minded senior member had revived at last. Saved by an admittedly inferior port he now made a strong sally to regain the oratorical high ground. Silence settled, if somewhat sullenly.

‘If we lose our rights in New Orleans we lose cotton. And if we lose cotton we lose half our economy. If we can’t get the cotton out then, dammit, how are we to pay for the slaves to be got in? Already there’s lily-livered abolitionists here in the North trying to hedge cotton around with dangerous and, yes I will say it, gentlemen, almost treasonous restrictions. Don’t honest businessmen have to get the basic labour necessary for their trade? That’s what we call economics, gentlemen, hard-headed economics. Not namby-pamby, addled clap-trap.’

Cotton-owning heads nodded, while others maintained a reserved silence.

‘Slavery is as old as time, the black man was made for slavery. Why it’s Biblical gentlemen, positively Biblical. I don’t say this just because I’m in cotton. You all know I’m in cotton. I’m proud to be in cotton because what’s good for cotton is good for America and what I always say is …’

Alas, the indifference of the port told. What the serious-minded member always said was lost to another violent fit of coughing which turned his face a little more the colour of the port he was again offered.

‘Gentlemen,’ another voice quickly took the vacant floor, ‘whether your business is here in the North or down South these are troubled times, war in Europe and divisions at home. I have no particular stand on slavery but facts are facts. No slaves means no cotton, and without cotton half an economy is what we’ll be left with.’

‘There’s serious talk the British are finally turning against slavery altogether. Not just the trading, mind, but the owning of slaves.’

‘Madness, sir, pure madness. It can’t be done.’

‘Madness perhaps, but ten years ago abolition lost in their House of Commons by eighty votes. Five years ago it lost by four. Don’t tell me, gentlemen, that there’s not a strong enough movement in the British Parliament to abolish the trade in slaves across their Empire. And if the trade goes then slavery itself soon follows.’

‘Never, sir, never. Why a world without slaves, well it cannot be a civilised world …’

But if business dominated these luncheon gatherings, scholarship was not altogether lacking. An educated cough brought a grudging but respectful pause. Learning wished to speak.

‘The problem with slavery, gentlemen, is that it has become symbolic of what some are choosing to call “The Rights of Man”. In doing so it sets business, or as our esteemed friend would have it, economics, against religion …’

‘Then damn all religion …’

‘Oh no, sir, not all religion. Just those misguided few who believe that this fallen state of ours can be made perfect on this earth by our own efforts. They’re idealists and of course one admires their ideals. But here on earth, gentlemen, history teaches we must deal with life as we find it. That means allowing that the Devil will always be somewhere at work in men’s affairs. And when that particular gentlemen gets involved then certain niceties, which we may all admire, must be foregone. As for the rights and wrongs of slavery, I can do no better than quote The Declaration of Independence, on which this great new country first took its stand as a nation. We all know and love those words, “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” …’

‘If you have a point, sir, damn well make it. This isn’t a school room nor yet a lecture hall.’

‘I will, sir, I will.’ But,having observed the fate of business, scholarship paused to take a drink of wine before continuing. ‘If we are to deal with the question of slavery …’

‘No question to deal with, sir. Always have been slaves, always will. Stands to reason.’

‘Quite, but as I was saying, let us look at the Declaration. Are slaves, black men and women, who are traded like cattle, to be considered as endowed by God, like you and I, with unalienable rights?’

‘Good point sir. Well made point.’

‘Biblical, gentlemen, positively Biblical.’

‘And mark the words that follow.“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from …” pause for emphasis, “… the consent of the governed”. Gentlemen I ask you, as men of business and of sense, are slaves among the governed? Do they vote? Are they free citizens like you or I? Or are they property?’

‘Well taken, sir.’

‘Might as well give a cow the vote and call it free.’

Laughter.

‘Good point, sound reasoning.’

‘Do they participate in and contribute to the political life of the country, gentlemen, as we all do? I think not, gentlemen, I think not.’

A dissenting voice intruded.

‘Clever words, perhaps, but what the hell has it to do with the matter in hand, sir?’

‘Only this. Businessmen may talk economics and governments write declarations but the cloven hoof will be there, gentlemen. Anyone who thinks otherwise need look no further than Santo Domingo.’

A silence fell and a hushed voice murmured.

‘Aye, Toussaint L’Ouverture.’

This brought a short, worried pause as heads nodded.

The scholar continued.

‘Toussaint L’Ouverture indeed. No slavery has been hi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...