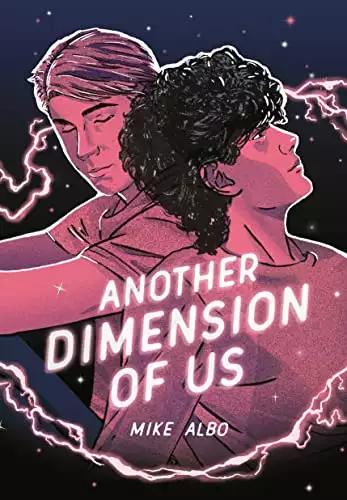

1986TOMMY

Tommy was crying, holding his head in his hands, saying over and over that he should have kissed Renaldo Calabasas that night when he had the chance.

It had been a week since Renaldo was struck by lightning. Tommy was sitting where it happened: under the charred tree in Hollow Pond Park, huddled into the base of the blackened trunk—the exact spot where they almost kissed. He wrote down his thoughts.

You are like smoke, a dark dance in the air.

No.

You are a storm cloud, weightlessly heavy.

No.

You are as mysteriously beautiful as black smoke.

No.

A crow.

No.

A raven?

Tommy crossed out his words. He was such a shitty poet. He wasn’t even a smidge as good as René. And his bad poetry couldn’t match what he was feeling.

But he kept writing in the book. He had to. Renaldo Calabasas was lost in the astral plane, floating somewhere in its expanse. And it was the book that told Tommy that if he wanted to find Renaldo and bring him back to Earth, he had to write down how he felt. He had to get close to him in words, and the words would be his path to him.

The book told him to write it all out.

The book. The book.

JUNE,

THREE MONTHS EARLIER

Tommy stood at the bike rack watching Renaldo Calabasas unchain his clunky old banana-seat Schwinn.

René was sweating through his white button-down shirt, and Tommy could see the contours of his chest through the wet fabric.

It was Friday, the last day of school, and everyone had cleared out in an end-of-the-year frenzy, ripping up and throwing away their schoolwork and locker decorations like they were getting out of jail. The trash bins next to them were filled with spiral notebooks, crumpled papers, tattered locker posters of Van Halen and the Doors. All the wealthy juniors and seniors of Herron High had driven away in their cars to some popular person’s party somewhere. Tommy wouldn’t know where.

“You ready to go?” Renaldo asked, piling books into his basket before stopping suddenly. He leaned against his bike and stared up at the sky.

“What are you looking at?” Tommy asked.

“I’ll come to you when the sky is cerulean blue,” René said.

“What?”

“That sentence. It came to me last night after a dream. Like someone said it to me. I’m just wondering if this is what ‘cerulean blue’ is.”

Tommy followed Renaldo’s gaze. The sky was strangely dark in color, like the coldness of outer space was closer than normal. Cerulean, cerulean, Tommy repeated to himself.

Renaldo rummaged through the bike basket and ripped out a page from his notebook. Tommy could see that there was a poem written on it titled “Storm Omen.” Even by sight, Tommy knew it would be good and that it would appear in the next Cornucopia—the student literary magazine they worked on. Everything René wrote made it in there.

“It’s about lightning,” René explained, still staring at the sky, “about this thing called keraunoscopy. Do you know that word?”

“No, sorry,” Tommy said. He wanted to say, Do you know how beautiful you are? But of course he didn’t.

“It means divination by lightning,” said Renaldo. “I mean, isn’t that the most amazing word ever? Apparently, the Etruscans believed that lightning and thunder were omens.”

Tommy only had a vague idea who the Etruscans were but nodded assuredly, anyway. Renaldo was so well-read. Lightning was his latest obsession.

“Lightning on a Tuesday or Wednesday was good luck for crops. But on a Sunday meant a man would die, a whole different thing. On a Friday, it meant something foreboding was coming. I wrote this last night. Well, technically, this morning after midnight, so it was on a Friday.” René talked quickly and floridly, like he always did, and Tommy ate up every word.

He scanned the page.

I am naked, only in my skin,

bare bark,

listening for storms

waiting for omens

Tommy couldn’t get the naked part out of his mind.

“Come on,” René said suddenly, snatching the poem back, “we have to get to the library.”

Tommy watched as he folded the poem meticulously into a triangle, like he was folding a flag for a soldier, and placed the little parcel in the front pocket of his shirt. Then he hopped on his bike, and Tommy quickly strapped on his backpack full of books and grabbed his bike, too, pedaling hard to keep up.

They rolled down Freedom Avenue. Tommy let René go first so he could watch him from behind, his hair flying, white shirt billowing in the hot air. It was the beginning of June, the air was humid, and every yard they passed was dense with green lawns, sprinklers chattering away in wet stutters.

Tommy wrote poetry, too, but never as good as Renaldo’s.

Except for the poetry he wrote about Renaldo.

About René’s dark curls that cascaded down his neck.

About his strong nose and deep brown eyes that were so open and expansive, they were almost like staring into a night sky filled with stars.

About René riding his bike in his strange white pants and white shirts that he always wore, sometimes with an equally unstylish fedora hat, his bushy hair peeking out from under it.

About his brown skin, not one freckle.

About his body that was wiry and skinny and surprisingly strong, even though he never exercised.

About his old poetry books that he was always carrying around, along with his giant hardbound notebook that he wrote in constantly.

About the callus between his left index and middle finger that had formed because he wrote so much.

About how René wasn’t popular but he didn’t care at all. Tommy wasn’t popular, either. That was for many reasons. But the big one: His last name was Gaye. And because life was apparently one giant cruel joke, he had always known he was gay, too. Last week he even said it out loud. He shut the door to his bathroom, making sure his parents and his brother were safely downstairs, and he looked in the mirror and whispered it to himself. I’m gay.

He muttered it quickly in the mirror so that he wouldn’t have to get close and look at his pimply skin and feel even worse about himself. But now he was with René and they were on their way to the library and school had ended and he was free, flying down Freedom Avenue, and René was on his bike in front of him. He felt jolted with life.

Just two hours ago, René had surprised him at his locker before last period.

“Hello, fine sir,” he said, miming the bow of a mannered gentleman from a different age like he always did. “See you at Ziller’s after sixth?”

“Yes!” Tommy answered, already regretting his enthusiasm. “I know Ms. Ziller wants to, like, say goodbye to us or something?”

“Yes. And what are you doing after?”

“Um. Nothing, I guess,” Tommy answered.

“Can you join me? I want to take you to the library and show you some of my secrets there,” he said. Tommy swore he winked as he spoke. It made Tommy’s heart leap.

René was talking about the public library, the one behind the Kmart in the middle of town. René had discussed going there with him for months, since they met at the beginning of the semester. It was his sacred space, where he checked out poets like Anne Sexton and Langston Hughes and Christina Rossetti—always someone new—and gave them to Tommy to read. At home, Tommy would dive into each page looking for messages. (Emily Dickinson was the hardest to decipher, but at the same time, strangely the most powerful, like her words were almost supernatural visions.)

“And anyway, I have to return that Anne Sexton book you keep hogging.” (He gave Tommy the poet’s Love Poems last week. Tommy had been poring over every word trying to find messages to him: “That was the day of your tongue / your tongue that came from your lips,” she wrote, and Tommy felt himself vibrate.)

“Sure,” Tommy said, trying to sound calm. Inside he was shining with excitement, but he had learned to not be so expressive, ever since his brother made him feel bad about it. (“You’re so . . . expressive,” Charley said when he caught Tommy dancing in his room to the Xanadu soundtrack.)

“Great. Well, I better make haste to what they call ‘PE,’ ” Renaldo said, making air quotes. “We have some sort of incomprehensible final fitness test we have to complete.”

“I hate PE with all of my being,” Tommy said.

“To my very essence, pure loathing,” René answered, and bounded off. “See you at Ziller’s!”

Ms. Ziller was their favorite teacher. She ran the poetry club and was the literary magazine supervisor. Tommy had spent a lot of time after sixth period in Ms. Ziller’s room this past spring. After winter break, he saw a light purple flyer on the bulletin board saying that Poetry Club was meeting on Thursdays after school. Something about the color alone made him know it was the right place for him.

It was just the three of them every Thursday—René, Tommy, and their friend Dara—and all they did was hang out and work on The Cornucopia and read poems or draw. When the door was closed, Ms. Ziller was funny and talkative and like their friend and not their teacher. Dara was the artist—lately obsessed with spiders, which in turn informed René’s writing to include cobwebs and entanglement. Every Thursday, René would show up with a new typed-out poem that Ms. Ziller would quickly

mimeograph on thick white paper, and Tommy would hold the wet, buttery paper in his hands and read another perfect work. Then Dara would pull out her charcoal pencils and begin an illustrated reaction to it like they were a jazz duo. Tommy’s friends were so talented.

Tommy had only one poem that he was proud of (but no way would he show it to anyone), called “More Than Friends.”

You look at me

Brown endless eyes

As if

You were sharing something

More than enough

A more perfect union

More than friends

He crumpled it up immediately. Then tore it up. Then ripped it into smaller pieces. And then ran downstairs and put it at the bottom of the garbage can in the kitchen.

“What are you doing?” his brother, Charley, asked, suddenly behind Tommy, surprising him.

“Nothing!” Tommy answered, trying to sound calm.

Ever since he and Renaldo became friends, Tommy had a vision. Or more like a daydream. He would be in bed still half-asleep after yet another night of wild dreams that made no sense, and like a movie under his eyelids, he would see himself and René, older, maybe even as old as sixty or seventy, in a house by the ocean. Tommy was in the kitchen making something (he had no idea how to cook anything but could in this daydream). He would finish cooking and bring the food out onto the porch, and there would be the ocean, not far away, crashing in relentless shushes, and René in his chair, with a book in his lap. Then Tommy would ask if he wanted some lunch, René would say yes and offer to help, and Tommy would say, No, no, keep reading. Then, Tommy would come up to him and stroke his long hair and kiss him.

Tommy wanted to do so, badly. But even though his best friend had asked him to come to the library, and summer was starting, he wouldn’t dare try to kiss Renaldo Calabasas.

And so, when the bell rang on that last day of school, Tommy walked through the trash-strewn hall to the back of the building, where Ms. Ziller’s room was at the end. The sign posted on the door read:

—Edgar Allan Poe

As if she had known, Ms. Ziller opened the door before he knocked and waved him into the classroom. She was wearing a sunset-orange turtleneck and tight bell-bottom jeans—so completely out of style, they were almost cool again. Behind her, on the walls, were other quotes in bubble letters on the bulletin board from people Tommy had never heard of: “You write in order to change the world,” said James Baldwin, and “Poetry . . . is the liquid voice that can wear through stone,” by Adrienne Rich.

Tommy slipped into a seat. René was perched on the top of a desk. Dara was leaning back in a chair, wearing her usual powdered white foundation and charcoaled-out eyes, her hair spiked up and standing on end like dynamite had exploded on her face.

“René told me you’re going to the library, so I don’t want to take up too much of your time,” Ms. Ziller said, opening and closing drawers, rummaging around in five different directions like she often did. “I have something for you guys, since I won’t see you till September.”

“Oh, I can’t go to the library,” Dara interrupted. “My parents are going out, and I have to babysit my little brothers,” she explained, and Tommy felt bad for feeling thrilled that it would just be him and René.

“Well, here you go,” said Ms. Ziller. She held out three slim gift-wrapped boxes. Inside each was a pen, heavy and gold, with a removable cap.

“Just a reminder from me to keep writing. All summer.”

“Wow. Thank you, Ms. Ziller,” said Tommy.

“Cool,” said Dara.

“It has a heft to it,” said René, weighing it in his hands.

“For heavy words. And light ones, too,” she said, almost embarrassed by her gift. “I just want you three to keep creating this summer. And be safe.” Tommy watched as tears pricked her eyelashes. She was getting emotional.

“Now go, get out of here!” Ms. Ziller composed herself and pushed the teenagers out the door.

“Have fun. I’ll see you guys tomorrow,” Dara said as she walked off in the opposite direction toward her locker. “We can watch this movie I rented.”

Tomorrow they all had plans to hang out at Dara’s. Tommy was already excited. Now he got to be alone with René. And then tomorrow, the hangout.

***

Tommy and René stepped into the library. It was empty. Just a smattering of old people concentrating on their magazines. A blast of air-conditioning chilled Tommy’s face, and his eyes darted around, trying to spot a bathroom so he could go to a mirror to see if his bad skin, his acne-covered skin, looked okay.

“I’ll be right back!” he said.

He was glad he did—in the bathroom mirror, he saw that two whiteheads had formed on his nose. He popped them immediately. He hated mirrors. He hated his skin. Furtively, he dabbed the little spots where he was bleeding until they stopped. Someone knocked on the door and he jumped.

“Hold on! Sorry!”

He washed his face and dabbed his skin again and quickly slipped out the door, an annoyed middle-aged woman staring at him like he was in there masturbating. He felt the wetness of his skin in the air and the tiny sting of his pimples.

Tommy found René in the reference section, standing before a giant dictionary set on a wooden podium. It was the biggest dictionary Tommy had ever seen. It smelled like museums.

“Here it is,” Renaldo said, introducing Tommy to it proudly, like it was his souped-up car. The pages were delicate and thin, the words so microscopic you needed a magnifying glass to see them. One dangled from the podium on a string.

“This is how I found keraunoscopy,” Renaldo told him.

Renaldo’s spectacular poetry was full of amazing words. He confidently sprinkled them into long, descriptive lines like a chef with herbs. Caveat, brindled, encomium. The Cornucopia was basically an excuse to publish Renaldo’s work. And Dara’s accompanying drawings, which were also amazing.

“So, if I ever get blocked or don’t know what to write about, I come here and just close my eyes and find a word, and then pow!” He made a head explosion gesture. The sudden movement made Renaldo’s white shirt lift up, and Tommy saw the hair leading down his stomach. “Other times I just walk through the poetry section and pick out books randomly and read a line or a stanza to try and get messages. That’s called poetic divination. James Merrill did it, and so did Sylvia Plath. A lot of the great poets used to do this.”

Tommy watched René glide his hands over the dictionary. He flipped through the book again.

“Augury!” he said. “Oh, I know this one. It’s a sign of what will happen in the future, like an omen. It’s a word from the Romans. The Romans loved omens. They even had, like, government-supported psychics called sibyls. But from what I’ve read, the Romans really owe their whole psychic knowledge to the Etruscans. Who were very observant about the planes.”

“Planes? There were airplanes flying around?”

Renaldo laughed and rested his hand on Tommy’s shoulder. Tommy felt electrified by his touch. “Not, like, airplanes. Meaning, like, areas. Planes of reality.”

If he wasn’t obsessing about poets, René was focused on ancient myths and magic. He often talked about spirits and other worlds like he really believed in them.

He pointed to the walls. “This,” he said, pounding the floor with his fist. “This, the earth we’re standing on, is just one plane. There are others!” He said this loudly, swerving his arms around.

The librarian looked up from the desk and glared disapprovingly.

René quieted down. “There isn’t just life and death,” he whispered. “The Etruscans, the Romans, the Mesopotamians, the Maya, all these ancient cultures thought that there were other planes—other places where we exist. They had way more respect for . . . elsewhere. Our culture, now, doesn’t respect that. Why do we think we are so much more evolved than them?”

René tugged at his hair again and then stared at Tommy with his deep brown eyes.

“Yeah, sure, sure,” Tommy answered with confused enthusiasm. “How do you get there, to this other place? I mean plane.” Maybe in this other plane, René would actually kiss him.

Tommy imagined it looked like one of those special episodes of afternoon soap operas where Sierra, the rich girl, and Locke, the stable boy, finally made love on a gauzy four-poster bed surrounded by a menagerie of lit candles and rose petals sprinkled on the comforter.

“Different cultures say different things,” Renaldo said. Then he grabbed Tommy by the shoulders and placed him in front of the huge tome. “Your turn.”

Tommy closed his eyes, flipped through the book, and moved his finger around the tissue-thin page. He opened his eyes to find his finger on projection.

“Cool,” Renaldo said encouragingly. “Projection. Like a projection into the astral plane!”

“The astral plane?”

“Oh! That’s what they call the other planes these days. I have to show you this book that I am obsessed with. It’s about traveling to the astral plane and how to do it.”

“Cool,” Tommy said, not fully understanding what René meant.

René stood up, grabbing Tommy’s hand. Tommy hoisted his backpack over his shoulders as they scurried through the tall stacks, down to an area that seemed like no one frequented it. It was in a corner. René crouched in front of a low shelf of books, dusty and undisturbed.

“Here it is,” he said, rummaging through the shelf to find a slim volume. The cover had a swirling illustration that looked like melted stained glass. Tommy saw the title emblazoned in scarlet letters.

“I check it out at least once a month. It’s full of history that you won’t learn at Herron,” René said, scooching next to Tommy to show him the pages. “There are several different methods to project. Some are super insane, like you swallow two worms in a glass of water. The Druids were all about hanging mistletoe.”

“Mistletoe? ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved