CHAPTER ONE

Eleanor

Fortune is like a widow won,

and truckles to the bold alone.

—William Somerville

London, April 1818

“What is the point of having money and independence,” Eleanor Lockhart asked, “if one must still be proper? I did not come to London to be staid and boring. One might do as much at home in Wiltshire.” Eleanor tugged the green ribbons of her new bonnet into a bow beneath her chin.

Miss Fanny Blakesley dithered before the front door to the fine town house Eleanor had rented for the Season, as though she might physically prevent the younger woman from leaving the building. “To go walking by yourself, and you so young? You’ll appear a sad romp.”

Eleanor picked up a pair of gloves from the table beside the door and slid them on. “I am seventeen and a half,” Eleanor said with dignity. “I may be young, but I have been married and widowed, so by anyone’s reckoning I am not a child, nor should I be treated as one. And I shan’t appear a sad romp at all, Miss Blakesley, because I feel quite elated. I shall smile at everyone I meet.” As if to prove her point, she smiled at her companion.

“Oh, Eleanor!” Miss Blakesley backed herself against the door, shaking her head so iron-gray ringlets trembled about her cheeks.

Eleanor’s merry expression faded. She had hoped that hiring an older woman as her companion would give her countenance to do as she pleased. Perhaps she should have sought a younger companion after all. “If you please, Miss Blakesley, I mean to go out alone. I shall be quite safe and keep to public thoroughfares. I do not pay you a handsome salary to thwart me, and if you persist in resisting me, I shall call the butler to remove you.”

Miss Blakesley moved hastily away from the door. “Only, do but tell me where you mean to go. Else I shall be so worried.”

Eleanor sighed. “I mean to walk to Green Park, perhaps as far as St. James’s Park. I have a hankering for fresh milk.”

“Isn’t that rather far?” Miss Blakesley asked. “Pray, do not exhaust yourself. And consider how it must look, to drink your milk in the open air like any commoner. Oh, and do stay away from St. James’s Street. No lady should venture there without a gentleman to accompany her.”

“I shall not exhaust myself, and I rather think people have better things to do than observe me drinking milk, should I get so far. Do not fret yourself so—I shall be back in an hour, perhaps two, and then you may accompany me. I must get the clasp on Mama’s necklace fixed.”

Miss Blakesley brightened a trifle. “Of course. Your dear mama!” She grasped her hands at her bosom, conveniently forgetting that she had no real knowledge of Eleanor’s mama. Nor, indeed, had Eleanor herself. “Might I suggest a fine jeweler I know of on Poland Street?”

“You may suggest whomever you like—after I return.”

Eleanor pulled her shawl more tightly about her shoulders, opened the front door, and stepped firmly down the stairs into a blustery April day. Not until the door shut behind her did Eleanor’s stiff shoulders ease.

Miss Blakesley was a decent woman, and the impoverished cousin of Eleanor’s deceased husband, Albert, besides. It was not her fault that she was a bore—at least, not entirely her fault. Surely she could temper what nature had given her with just a bit of exertion. But Eleanor knew what it was like to be poor and desperate, and she could not find it in her to turn the woman away.

A brisk wind chased down Curzon Street, blowing Eleanor’s brown curls into her eyes. She tucked the hair back beneath her bonnet and strode on. The chill wind might have daunted a soul made of less stern stuff, but not Eleanor. It felt good to be out of doors, alive, and in London.

She admired the tulips bobbing along her route and nodded to a gentleman and a lady who looked vaguely familiar. While the gentleman returned her nod rather stiffly, the lady pretended not to see her. Perhaps they had not yet met, after all.

Or perhaps Miss Blakesley was right, and it was truly not done for a woman—even a widow—to walk alone.

Well, Eleanor did not care. She was finally in London, free of the stifling walls of Lockhart Hall, free of the small town where people were kind enough, but where she would always be known as the little nobody who had snagged the rich Mr. Albert Lockhart. She knew people had looked askance at her when she married a man old enough to be her father (whoever that had been), but Albert had wanted a wife and heir, and she had needed a home, rather desperately. At least Albert had been kind.

She sighed. Albert had always meant to bring her to London, to show her the museums and the gardens and the society parties. But then he had contracted putrid throat less than a month after their marriage and died shortly after. She had mourned a full year for a marriage that had not lasted nearly so long. Poor Albert.

She shook herself. She would not be maudlin, not now, not ever.

Eleanor passed by a small church. Miss Blakesley had pointed it out on their arrival as the site of many clandestine marriages in the eighteenth century, including that of one of the famous Gunning sisters. Eleanor had some fellow feeling for Miss Gunning, as an impoverished young woman catapulted beyond her station by her marriage to a duke, though once widowed, Miss Gunning had rapidly married another duke, and Eleanor did not mean to marry again.

She understood how fortunate she was to have her own money and her independence—she would not jeopardize that.

Making her way down Half Moon Street and alongside the railings lining Piccadilly, Eleanor at last reached the gate into Green Park and slipped in. It was blessedly quiet beneath the canopy of trees fringing the meadows—too early still for the fashionable crowds who gathered of an evening. Eleanor followed a narrow pathway, spying a late daffodil waving like a yellow flag at the world.

She intended to trace the path south and east until she reached St. James’s Park, but she had not gone far before she found herself accosted by a tall, well-dressed gentleman.

“Eleanor,” the man said, and everything inside her seemed to curdle.

“Mr. Lockhart,” she said, refusing the familiarity her husband’s nephew seemed determined to force upon her.

He frowned down on her. “What are you doing abroad, alone?”

Eleanor didn’t dignify his question with an answer. “How did you find me?”

“I called upon you at home,” he said. “I have procured vouchers to Almack’s for you and Miss Blakesley.”

“To the marriage mart? How … kind.” But was it kind? George Lockhart had considerable motivation to see her married again, given the conditions of her husband’s will. Eleanor did not know what to make of her husband’s nephew, who had been polite to her the few times they had visited, even if he was a rather indolent man, and disinclined to bestir himself for others. He was handsome, if one liked men with tallow-colored hair and long noses, but she suspected he disliked her, though she had no reason for her belief other than the flat look she sometimes caught in his eyes when he was watching her.

“As you are new to town and have no one to advise you how to get on, I took it upon myself to call on Countess Lieven. I am sure you will wish to be comfortably established in society sooner rather than later, and I can escort you myself Wednesday next.”

“Thank you,” Eleanor said, “but I do not believe Miss Blakesley or I need you as an escort.”

Was it only her imagination, or did his brows twitch at that? “As you wish, though I think you may soon discover that it is more comfortable to have a male companion at such events.”

Eleanor began walking again, hoping that Mr. Lockhart, having accomplished his errand, would leave her in peace. He made her feel like a child, though he was not more than half a dozen years older than she.

Instead, he fell in step beside her. “May I accompany you?”

No, you may not, she thought crossly. But she didn’t say that. She might not like Mr. Lockhart, but he was the closest thing she had to family, and she could not bring herself to burn all her bridges. That did not mean she had to entertain him, however.

They walked in silence toward St. James’s Park. As they crossed into the park, Mr. Lockhart said, “Your country upbringing is showing. No London-bred lady would indulge in so hearty a walk. Shall I escort you home? My carriage is just outside Green Park.”

Eleanor stiffened her back and her resolve. “If the walk is too much for you, by all means, return to your carriage. I shall go on.”

“I assure you, my advice is kindly meant. You have not been much in society, having married my uncle direct from school. I would not see you barred from society before you have begun your conquest.” His blue eyes glinted at her, his thin lips pressed together. Was that a warning?

Eleanor tamped down a flare of anger at his presumption. She would not give Mr. Lockhart the satisfaction of seeing her react.

They walked on, coming eventually to a round, rosy woman with several cows clustered around her.

Mr. Lockhart sighed. “What are you up to now, Eleanor?”

Eleanor looked at him innocently. “Did not Miss Blakesley tell you? I mean to try the milk in the park. You must try it too—please, it shall be my treat.” Eleanor had had the foresight to bring a small pewter cup with her from the kitchens. Fetching it from her reticule, along with a coin for the milkmaid, Eleanor approached the woman.

Mr. Lockhart’s lips tightened in irritation. For a moment, she thought he would refuse her, but then his eyes went to the woman watching them and he forced a smile.

The milk was warm and frothy and considerably better than that which was delivered to the house, which Eleanor suspected was watered down.

In any case, it was worth all the displeasure of Mr. Lockhart’s company to see him choke down the liquid in a cup the milkmaid offered—a drink, he would tell her in an undertone on the way back to his carriage, that only children and fragile young maidens partook of.

Eleanor ignored the jab at her spurious fragility, and reassured Mr. Lockhart that no one seeing him drinking the milk would assume he was either a child or a maid.

“Of course not,” he said. “But they might think us both witless.”

“Surely not,” Eleanor said, smiling sweetly at Mr. Lockhart as he helped her into the carriage. “That would require them to suppose you had wit to begin with.”

Mr. Lockhart’s hand tightened around hers, and the strength in his fingers sent a sudden chill shooting through Eleanor. Had she said too much? For a moment, he looked as though he would like to strangle her. But he only released her hand and leaped lightly into the carriage, picking up his whip before remarking, “She hath more hair than wit, and more faults than hairs.”

Eleanor recognized the line from Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona. She had been taught something at school, after all, before the sudden cessation of funds from her unknown father had forced her out. Was Mr. Lockhart trying to return her insult?

She folded her hands in her lap as the carriage jolted forward. Do not engage, she told herself. But Eleanor had always favored valor more than discretion, and she could not pass up a good sally. “You forgot the last part.”

Mr. Lockhart gritted his teeth. “And what is that?”

“She hath more hair than wit, and more faults than hair, and more wealth than faults,” Eleanor said. “I should rather be accounted witless than penniless, wouldn’t you?”

Whereupon Mr. Lockhart, whose expected fortune had gone to Eleanor on his uncle’s marriage, growled something unintelligible and did not speak to Eleanor again until depositing her on her doorstep—and then, it was only to wish her a rather curt “Good day.”

* * *

The jeweler’s shop Miss Blakesley directed their coachman to that afternoon was a neat little building tucked between two teahouses. The mullioned windows let in abundant light that gleamed off clean counters and sparkled off jewelry nestled on black velvet displays. Eleanor, rather to her own surprise, approved.

The middle-aged proprietor, Mr. Jones, looked up from a conversation with a customer as they entered. Smiling widely at them, he said, “Good afternoon. We’re a bit shorthanded today: our regular shopgirl is out sick. But I’ll have my son show you anything you want.” He turned and shouted behind him, “Owen!”

A young man with the same heavy eyebrows as his father emerged from a door down a narrow hallway tucked to one side of the room. He was tall and thickly built, and he looked rather harassed, frowning at the company until a significant look from his father made him blink and clear his expression. He made his way toward Eleanor and Miss Blakesley.

“Oh, Eleanor, do but look at this cunning brooch!” Miss Blakesley said, inspecting a miniature silver peacock with a tail of sapphires and emeralds. It was quite lovely, though a bit florid for Eleanor’s tastes.

The young Mr. Jones studied Eleanor. His eyes were dark and warm, and when they met hers, something inside her pinged, as though with recognition, though she was sure she had never met the man before. “Are you in the market for such a brooch? Gold would suit your coloring better, I think.”

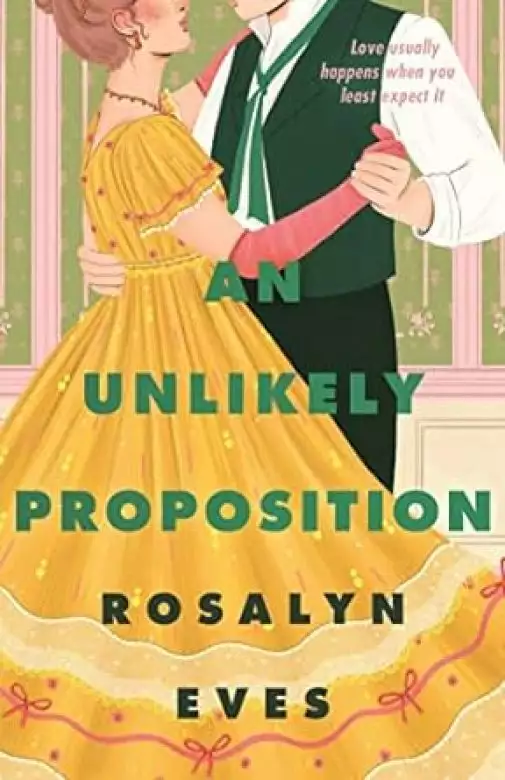

Copyright © 2024 by Rosalyn Eves

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved