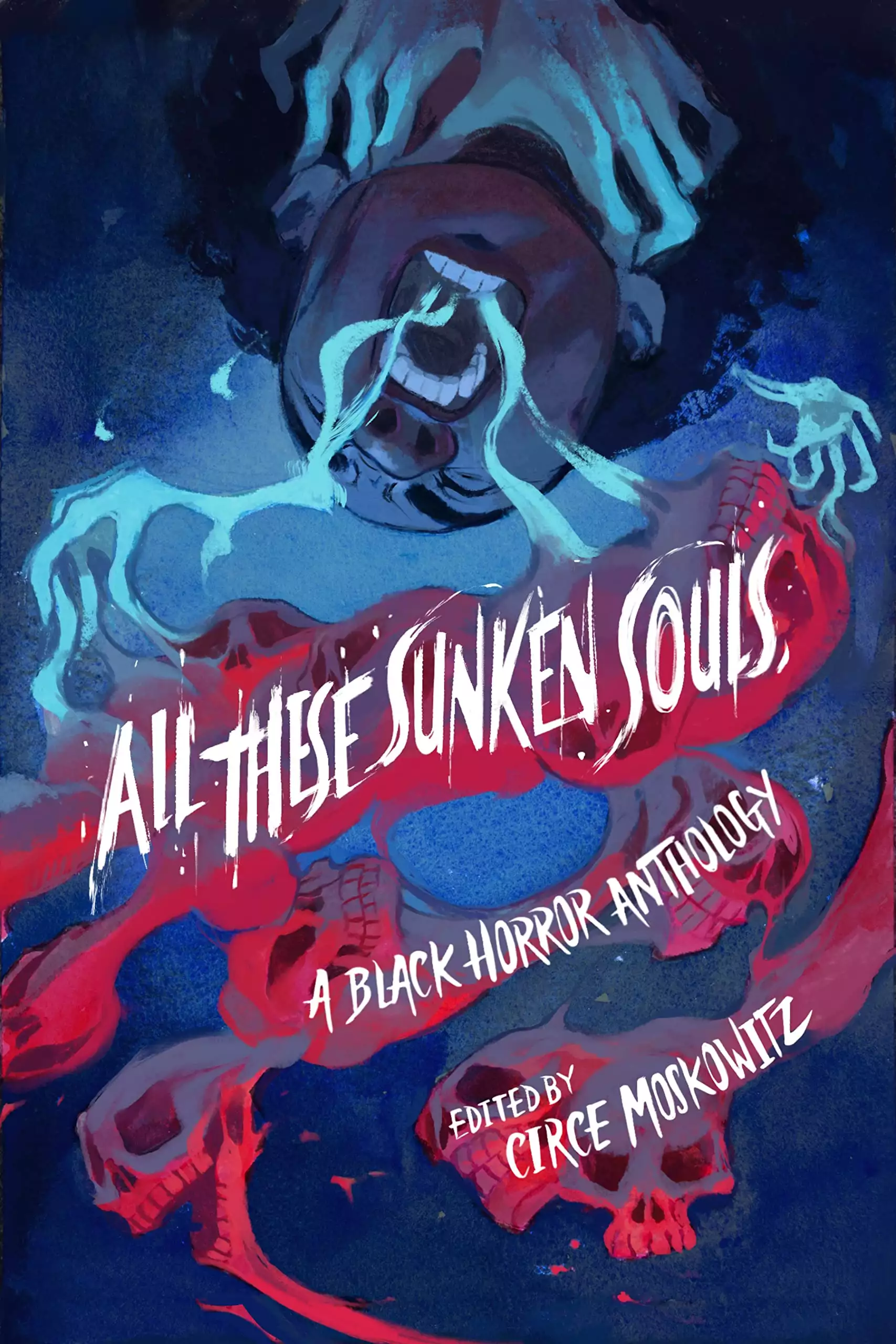

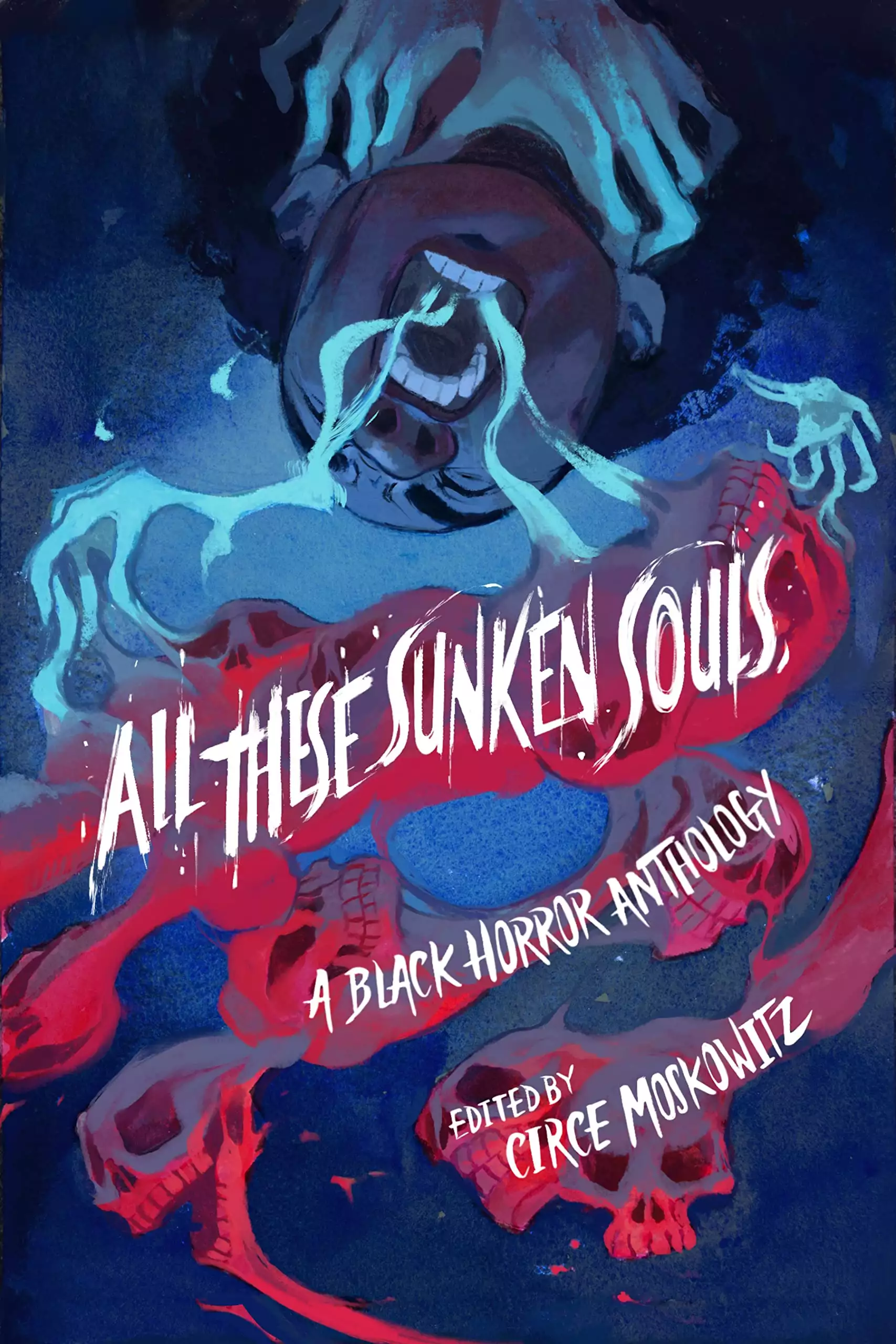

All These Sunken Souls: A Black Horror Anthology

- eBook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

We are all familiar with tropes of the horror genre: slasher and victims, demon and the possessed. Bloody screams, haunted visions, and the peddler of wares we aren't sure we can trust. In this young adult horror anthology, fans of Jordan Peele, Lovecraft Country, and Horror Noire will get a little bit of everything they love—and a lot of what they fear—through a twisted blend of horror lenses, from the thoughtful to the terrifying.

From haunted, hungry Victorian mansions, temporal monster–infested asylums, and ravaging zombie apocalypses, to southern gothic hoodoo practitioners and cursed patriarchs in search of Black Excellence, All These Sunken Souls features the chilling creations of acclaimed bestsellers and hot new talents.

- - - - -

Contributors

Kalynn Bayron @KalynnBayron

Ashia Monet @AshiaMonet

Liselle Sambury @LiselleSambury

Sami Ellis @themoosef

Joel Rochester @fictionalfates

Joelle Wellington @joelle_welling

Brent C. Lambert @BrentCLambert

Donyae Coles @okokno

Ryan Douglass @ryandouglassw

Circe Moskowitz @circemoskowitz

Release date: October 17, 2023

Publisher: Amberjack Publishing

Print pages: 292

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

All These Sunken Souls: A Black Horror Anthology

Circe Moskowitz

Lights

What is the punishment for murder? I guess it depends on who you are and how much money you have. If you have the money, you can get away with just about anything. I’ve seen people with good lawyers and deep pockets get away with all kinds of stuff. Murder is sometimes the tamest thing rich people get away with.

If I get caught, I will not get away with this. I know that already, and it is something I have come to accept. I don’t have money or a lawyer. I don’t have anything—except this pressure on my throat. It’s like an invisible hand slowly tightening around my neck, threatening to choke the life from me. It’s been bad for a while now, but it can get better.

I know exactly how to ease this terrible, suffocating feeling. The last time I needed to release the pressure was right after my latest birthday. I’d found a guy living alone in a ground-floor apartment. He’d left the window open. Nobody who valued their safety would ever leave their window open. It was an invitation, and it was so easy. The kill was slow, and the relief was immediate. I was satiated, and the fullness lasted longer than it ever had before. Probably because I took my time with him. I learned in those long moments that if I could prolong the kill, the tightness in my chest and neck would lie dormant for much longer. It’s hard to believe it’s been a year since then. I’m proud of myself for holding out this long, but I can’t do it anymore. I have to relieve the pressure, and I’ve given up pretending that anything other than blood and agony can ease this precious ache.

I’ve staked out the house for almost a month. The dad is a cop, but I don’t know if he’s a good one or not. He looks like somebody who could be hiding a secret. That badge gives him power, and maybe he uses it in a way he shouldn’t. The mom works at a bank. She wears the same gray suits every single workday, and she walks with her chin up and her chest poked out, like she’s better than me. She makes my skin crawl. And then there’s the kid. I don’t like kids. There is something repulsive about them—the timbre of their voices, their wide, wondering eyes. He’s nine or ten and goes to the same elementary school I went to when I was his age. He doesn’t seem to hate the place like I did. He’s always got some new thing to share or story to tell when his mom comes to walk him home every day at 3:30 PM. Maybe he doesn’t have someone there every single day making him wish he’d never been born.

Dad’s shifts are all over the place. He pissed somebody off at work, and for the past month he’s been working fourteen-hour shifts instead of twelve. I know because his coworkers don’t shut up about it on his days off. Their chatter over the police scanner is endless and annoying, and I wonder if he ever listens in the way I do. He is predictably absent.

The mom works a seven-to-three Monday through Friday. I watch her leave every day. I watch her come home every day. I rotate locations, so she

doesn’t catch on. It never fails to amaze me: people can be so unaware of their surroundings. They don’t stop to think that someone might be watching, that with one small misstep they might put themselves in my path and by the end of the day they could by lying face down in a pool of their own blood. That is what happened with this stupid kid and his arrogant mother and his failure of a father. They strolled right past me on the boardwalk over a month ago. The mother got so close I could smell the sweat on her skin. It stirred that thing inside me, and now I know what I have to do.

Every Tuesday, Mom and Dad take the kid to a therapist, and when they return home, they don’t wait until they’re inside to talk about how the kid is learning to get a handle on his anxiety and how they’re so very proud of him.

They treat the kid the way experts say he should be treated. They don’t shun him for making up stories. They don’t make fun of him for the things he says or what he feels. They got him some help. Good for him. Not everybody gets to have their mommy and daddy give a shit about what’s keeping them up at night. They’ve tried therapy, but maybe what he needs to make him get his head together is a stiff backhand and a few evenings without food or water. I know I should be moved by the care and concern he’s shown by the people who supposedly love him, but I’m not. All I feel is the pressure on my neck and the urge to do whatever I can to make it go away.

I took the bus to their neighborhood the day before, keeping the zip ties hidden in my pocket and the hunting knife well out of sight. I slept in the park two blocks from their house. Now, it’s Wednesday. Dad went in late in the day, and that means he’ll stay gone till much later. That leaves just Mom and the kid.

I watch the mom from across the street as she gets home and stomps up the sagging porch steps. She goes inside, changes her clothes, and walks to get the kid from school. This is their routine. I know it by heart. Thirty minutes and they’re back. I have thoughts of starting early, but I push them aside. I have a plan, and it always works better when I stick to it. I need to be focused, disciplined. I wait until the dark is pulling itself across the sky before I cross the street and enter their backyard through the side gate, which is closed with a rusty latch that doesn’t sit right in its cradle. I can easily lift it from the outside and slip inside.

The house is one of those cookie-cutter-type places. Every house on the street looks like a slightly different version of this one: one level over an in-ground basement, stucco exterior walls, an orange Spanish-tile roof, brick pathways, and an asphalt driveway. These houses were probably really nice once, but now they’re all in various states of disrepair. They’re still houses. Single-family houses, not shitty apartments with no heat and loud neighbors. Unfortunately, there are almost no trees on this street. No cover.

Beyond the gate, there’s a square slab of concrete just outside the back door of the house,

and on it is a set of chairs and a glass table with an umbrella sticking up out of the middle. There’s one tree in the far corner of the overgrown yard.

I stand at the side of the house, just inside the gate but outside the range of the floodlight that is constantly lighting up their backyard. They never turn it off, which annoys me to no end. Do they know that turning off the light would make all of this easier? Are they doing it just to mess with me? My heart kicks in my chest. The pressure on my neck intensifies. I let my fingers dance over the handle of my knife. I want relief from the pressure. I want to be satisfied for as long as this kill will allow. I take a deep breath and sink down in the grass. Patience is something I have had to cultivate. The vise grip on my neck is driving me forward, but rushing means mistakes will be made. I’ve had two close calls since this began, and they both came about because I was impatient, impulsive; the relief from them was fleeting. No mistakes. Not now.

With my back pressed to the exterior wall, I can hear the muffled sounds of a TV—some kids show with a grating song repeated over and over.

Thirty minutes later there is a soft click as Mom unlocks the sliding glass door and slips out onto the patio to have a cigarette. She does this whenever she can, always when her husband is at work and her son is preoccupied.

I know your secrets. You can’t hide them from me.

She smokes because she’s one of those people who has trouble settling down. She’s constantly on edge. Her husband hates the smoke. I hear him tell her he can smell it on her sometimes, and she denies it. She’s a liar and not a very good one.

I don’t move or breathe as I listen to her inhale the smoke and expel it in long, soft breaths. From my hiding spot at the side of the house, I can’t see her, but I can imagine what she looks like there under the floodlight: average height, warm-brown skin, braids that she usually keeps piled on top of her head. She and her son share the same deep-set eyes, the same round face.

One big breath and another huff. A cloud of smoke wafts into view and lingers in the cool night air. I breathe in, and I can taste the mixture of tobacco smoke and her hot breath. A tapping sound tells me she’s put

the cigarette out and will probably take the butt inside with her. There are never any used cigarettes on the ground or in empty jars on the patio. No evidence left behind. She’s almost as good at covering her tracks as I am, but her husband sometimes tells her he’s found the sooty remnants of where she put the cigarette out. I guess that’s the cop in him. He found the evidence of her smoking habit but didn’t find any trace of me.

I hear the sound of the glass door rolling open, then closed again. No sound of the lock clicking. It’s my lucky night after all.

I wait. I imagine her going inside, maybe settling down in front of the TV, the kid at her side. I’ve seen her do this before. She bottles up that nervous energy around him, probably tries to make him feel like there’s nothing she can’t handle. It is arrogance, the very same arrogance she displays when she struts around with her chin up.

I peer through the kitchen window. I can see the back of her head as she sits on the couch and flips through the channels. Her hair is long enough for me to wrap around my fist. The kid isn’t with her yet even though I thought they’d be sitting together. Maybe she’s not such a good mother after all. I catch sight of the kid tracing his hand along the wall as he comes down the hall in his stocking-covered feet. He walks heel to toe in a straight line. The lights in the hallway are on, and much like the floodlight outside, I’ve never seen them get turned off. Not even when I watched them in the small hours of the morning. Their bill must be sky high, but they don’t seem to care. Must be nice having money to burn. I prefer the dark, but there is something in my gut that tells me they think these lights will keep them safe from me. It is a challenge I have willingly accepted, because I need them to understand that they cannot hide. The light will not chase me away.

The kid tiptoes into the living room, and balancing along the edge of the severe contrast of shadow cast by the couch, he joins his mother and leans his head against her shoulder.

In my head I know that seeing a young child sharing a tender moment with his mom should be touching in some way, but I feel nothing. I recall my own mother and how hard it was for her to look at me, let alone hold me next to her on the couch. She said I looked too much like my father and she hated him. The pressure around my throat tightens as the images flash in my mind.

The kid decides on a show, and he curls up amid a nest of blankets. I dig my fingertips into my forearm. This isn’t what I want. Walking in under cover of dark won’t be an option. They want this to be difficult for me. They think they are smarter than me, better than me. They

are not.

Rocks litter the side yard—leftovers from the little stone wall that used to ring a garden long since strangled out by weeds. I palm a small, round one and chuck it across the yard. It smacks against the fence on the far side, and the kid’s mom turns her head just slightly, angling her ear toward the noise. The television is on, and a laugh track drowns out the noise just enough for her to doubt what she heard. Frustration flows through me, but I tamp it down.

I pick up another stone, wait for a lull in the TV’s babble, then send the stone flying. This time, Mom stands up, leaving the kid on the couch as she goes to the window. My plan is working.

She cups her hands around her face and leans close to the dining room window, which faces the back of the house. The floodlight illuminates the rear yard as she stares out.

I could let her see me. I could walk into the rear yard, into the light, and let her understand that this will be the last night of her life, but I restrain myself because that won’t work. Too much time. Too many doors between us. She could slip away, and then I’d be on the run again, and the pressure on my neck would be more suffocating than it already is.

She pulls the curtains in the dining room. Mom says something to the kid, and he shakes his head no. As she stands there, hands on her hips, head tilting to the side, the kid gets up and skips into the kitchen. I duck away from the window for a moment, then slowly peek back through.

The mom has retaken her place on the couch. She reaches for her cell phone, then stops herself.

“You’re overreacting,” I whisper. “It’s nothing. You’re safe.”

She puts the phone back on the table, and her shoulders rise up then slowly relax.

“That’s right,” I say under my breath.

The kid grabs a bag of chips from the pantry, standing on his tippy-toes to reach. Just as he’s about to rejoin his mother in the living room, he stops and turns directly toward the kitchen window.

I stop breathing.

The lights are bright inside, but the area outside of the window is obscured by enough shadow

to keep me hidden—at least I think it is. He shuts his eyes tight, and I duck under the window, my heart crashing inside my chest. Footsteps pad over to the kitchen window, and another light flickers on. The footsteps retreat.

After several minutes I slowly stand and peer through the window again. My heart is pumping, and the rush of blood in my ears is so loud. Mom pulls the groggy kid to his feet and nudges him toward the hallway, and he stumbles lazily into the bright light that never goes off. His mom takes his hand and leads him out of my line of sight.

I quickly move around the outside of the house, skirting the floodlight, and come up on the opposite side. Through a narrow window, whose shade is up just enough for me to look inside, I watch as Mom tucks the kid into bed. He smiles at her, and she touches his face. It makes me physically sick to see them this way. She’s smothering him. He’ll probably grow up to be just as disappointing as his father.

She leaves the room without turning off a single one of the kid’s half dozen night-lights and only flicks off the daylight-bright bulb in the domed light in his ceiling. I grip the windowsill until my knuckles ache. I’m not here for the kid, but maybe I could be. Would two slow kills keep the grip on my neck at bay for even longer? I’ve never considered it, but here’s an opportunity to test the theory. I can almost feel the relief flood through me as I imagine the light leaving her eyes with the kids’ dimming soon after.

Several quiet moments tick by, and then he changes position, rolling dangerously close to the edge of the bed. One of his bare feet slips from beneath the blanket and dangles over the side. The kid jolts out of a nearly sound sleep and pulls his knees to his chest. He gathers the blankets around him and rocks back and forth glancing down at the floor.

The kid is afraid of the dark. Not just afraid—terrified.

I put my hand over my mouth to keep from laughing out loud. Stupid kid. There are much worse things to be frightened of. His mother didn’t neglect him. His father didn’t beat him. He wasn’t left to fend for himself.

Pressure on my neck.

I sit my hand under the windowsill and press up just slightly. It doesn’t budge.

The kid untangles himself from his nest of blankets and slowly slides from his bed, planting his feet firmly in the swath of pale blue light emanating from a night-light shaped like Captain America’s shield. He stands there like a statue, barely breathing, his back toward the window

I could grab him now if the window wasn’t locked. I could get my hands around his throat before he had a chance to scream. But the kill would have to be quick. And that’s not going to do me any good.

He takes one step toward the door.

Then another.

He keeps his feet in the wash of light like a gymnast on a balance beam. I wonder what happened to make him so fearful. Couldn’t have been as bad as the things that have happened to me in the dark, and this kid has a mom who keeps every light in the house on for him. The kid should suck it up.

He tiptoes to the door and disappears into the hallway. A moment later he returns with a little plastic cup, filled to the brim with water. He gulps it down and wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. He goes to set the cup on his nightstand when suddenly, his trembling hand brushes the cup, and it tips over and bounces to the floor, rolling into the far corner of the room where the glow from the night-lights is obstructed by his chest of drawers. His entire frame goes rigid. He turns his head in that direction, and his mouth moves as if he’s speaking. I narrow my gaze, trying to read his lips: monster.

“No,” I say in a whisper. “Not there. At your window.”

His mother abruptly appears in the doorway. Her gaze flits to him, to the shadowy corner, and then to the floor at her feet. She rushes to the kid and gathers him to her chest. They exchange words, whispers I can’t hear, but his mouth makes that same shape.

After several moments, he calms, and his mother tucks him into bed. She leaves without retrieving the cup.

I slide down the outer wall and sit in the grass against the side of the house. I do not have time for this. I move around to the opposite side of the house and peer through Mom’s bedroom window. She has shades, not curtains, and she’s got them pulled halfway down. The lights in her room rival the kid’s. She’s got a collection of lamps of various shapes and sizes. A tall floor lamp with a gold base stands in the corner, casting a cone of light onto the ceiling. A bedside table cradles a small desk lamp with a dark green shade. The closet light is on. The bathroom lights are on. Every goddamned light is on. Even though the kid rarely ventures into her room after dark, it seems she keeps the lights on for him in there too. She treats

him like some helpless infant. It’s pathetic.

The mom climbs into bed and pulls a sleeping mask down over her eyes. A ripple of anger courses though me and coalesces into a tight ball in the center of my chest. Just cut off the fucking lights and stop making me play this game. I’m ready to relieve this terrible ache, and this woman, this sorry excuse for a mother, thinks she can get in my way? I imagine choking the life from her with my bare hands. I’ve never strangled anyone before. I wonder how that might feel.

I press up on the window and find it locked. Mom stirs, and I duck down again. I’m done watching and waiting. The pressure on my neck is suffocating. I need to relieve it. Now.

I return to the rear yard and stand in front of the sliding glass door. The wooden dowel that is supposed to be laying in the track is standing straight up. Mom forgot to lay it back down after her smoke. A pattern she repeats entirely too often. Grasping the handle, I slide the door open, lifting it slightly to alleviate some of the pressure on the track that runs along the jamb. It squeaks sometimes when the kid yanks it open. This way, it glides with only a faint rustle that is masked by the gentle flush of the AC kicking on inside.

After all these weeks of watching from the outside, now I’m inside for the first time. The grip of the invisible hand around my throat loosens just slightly. I breathe deep as a sense of calm washes over me. I’m right where I need to be.

I don’t like the brightness—the lights, the off-white paint on the walls—it makes me feel exposed. It smells like vanilla air freshener, with some hint of whatever they had for dinner mingled in. I tread softly into the kitchen and try to flip off a light switch near the refrigerator. My fingers slip over the switch, and I realize there’s a piece of clear tape holding it in the on position. A switch on the opposite wall is taped up in the same way. Anger bubbles up again, and I scratch away the tape and hit the switch. The light fixture over the dining room table flickers out.

I turn toward the hallway, but somewhere over my shoulder, from the newly darkened dining room, there is a sound. I glance behind me. There’s nothing there. A light from a passing car casts a shadow across the floor under the table, and a wave of fear ripples through me. I pinch the skin on my forearm to distract myself.

Think of how good you’ll feel when this damn pressure is off your neck.

I proceed down the hall, taking the knife from my pocket and holding it up in front of me. The kid’s door is open, and he’s sleeping soundly. His chest rises and falls in a slow, steady pattern. The knife is cool and heavy in my hand. I step toward his room. The suffocating pressure in my neck surges. This isn’t the plan. Mom first. Kid last.

I gather myself and continue down the hall. Slipping into the mother’s bedroom, I stand at the foot of her bed, watching her sleep. People are so vulnerable when they’re sleeping. They’re completely oblivious to the world around them. It’s not fair. I never sleep so soundly.

Taking care not to make a sound, I move to the head of the bed and put my knife to the side of her neck. She stirs and reaches up to pull her sleeping mask away. This is the first time she’s really seen me, but I’ve been watching her for so long it feels like we know each other.

“What—” She registers the knife. She tenses, glancing frantically down the hall.

“He’s asleep,” I say in a whisper. “I won’t hurt him if you do what I tell you to do.” It is a lie, and I think she knows that.

“Who are you?” she asks. “What do you want?”

“Does it matter?” I put my free hand on my neck. I just want to be free from this pain, and killing has been the only thing in the world that has helped. It’s a curse, but it’s the only way. I reach into my pocket and take out the zip ties. She doesn’t struggle as I bind her wrists and ankles, but she pleads for her son.

“He’s just a baby,” she weeps. “Please. You—you’re so young too. What’s wrong? Can I help you? Is there anything I can do?”

“He’s not a fucking baby even though you treat him like one,” I say. “Shut up.” I don’t have time for this. I can feel the grip on my throat loosening. I’m almost free. With the knife in hand, I eye the targets, places where it can go deep that won’t kill her immediately. This has to last if I’m to get any sense of peace.

From down the hall, a thud, then footsteps.

I slide the sleeping mask down, and it muffles the mother’s pleas. Now she’s struggling, and I can’t keep hold of her. I try to grip her arms, but she kicks out with her bound feet and sends me careening into the side table. The lamps crash to the floor, the delicate bulbs shattering, their lights sputtering off. Pain rockets through my back.

“Oh no,” the mother whispers through the makeshift gag. “No. No. No.”

A rush of anger engulfs me—the lights? Fighting back? No. This is not the plan! She starts to hop toward the hall, but I cut her off, shoving her in the back. She can’t keep herself balanced, and she falls into the dresser. Her head strikes the corner with a deliciously sickening crack, and she collapses into a heap on the floor, unconscious, blood staining the carpet.

I slam my hands against the wall and clench my jaw so tight it pops, sending pain creeping up to my temple. Everything is going to shit, and I know what that means for me: long nights on back roads, no sleep until I’m far away. No. No fuckups this time.

I can make this right. There’s still time.

I grip my knife and stalk down the hall to the kid’s room. My neck feels like it’s in a vise. The pressure mounting behind my eyes makes me dizzy but eases just slightly when I see his form shrouded beneath the blankets on his bed.

I rush in and yank away the covers only to find his collection of stuffed animals. Crouching, I peer under the bed. He’s got battery-powered night-lights illuminating the underside, but he’s not there. I scramble to my feet as a hollow noise sounds from behind me. The kid’s plastic cup skids out from under his dresser. It’s dented on one side, and part of the lip is missing, leaving a jagged edge. I pause. I cannot take my eyes off the cup. What the fuck happened to it? I scan the shadowy corner of the room, then kick the cup away and move out into the hall. I have to get to the kid.

Down the hall, the lights are still blazing bright. My knife drawn, I come upon the kid, who’s standing in the center of the living room. He’s flipped on a switch, and a cone of clear, white light surrounds him like the beam of some alien craft ready to whisk him away. The bright lights are overwhelming, and I think of smashing the fixtures but stop myself. I don’t want to chase the kid around.

I tuck the knife away and stand very still as the kid trembles. His Spider-Man pajamas are a size too big, and tears are streaming down his face. He’s absolutely pathetic.

“Were you even going to try to hide?” I ask. “Or escape?”

He shakes his head.

“Well, that’s no fun,” I say. “Go. Go hide. It’ll be a game. Look. I’ll even cover my eyes.” I put my hand over my face, but I can still see him between my fingers. He deserves another chance to hide—to at least feel like

he did his best to save himself. He skirts around the coffee table and jumps into a square of light cast by a lamp in the far corner of the room.

I sigh and drop my hand. “Why are you so bad at this? Try harder.” His inability to find a decent hiding spot stokes a wild rage in me. Does he not understand, or does he not want to do what I’m telling him? There’s a coat closet; there’s room under the dining room table that’s also now shrouded in darkness, thanks to me. He could choose either one of those, but he doesn’t.

The kid slides along the wall and stands stock still next to the open closet. I expect him to duck inside, but he just stands there, eyes wide and wet, mouth drawn into a quivering frown.

“Are you stupid?” I ask. “You must be the dumbest kid I’ve ever known.”

His gaze darts from me to the space under the dining room table, then to the door that leads to the basement. My heart kicks up. Yes. Getting him down there will make this easier than it already is. There are no windows down there and only the one door.

I tense my body and flinch at him as he makes a break for the door. He throws it open and darts down into the dark. He must be terrified, seeing as he couldn’t even sleep in his own room without his collection of night-lights and lamps.

“Daveed!” the mother’s voice calls, hoarse and tinged with fear. “Daveed! Baby!”

“It’s okay,” I call out to her. She’s restrained. She’s injured. I’m not worried about her. “Don’t mind us. We’re playing a little game of hide-and-seek in the basement. It’ll all be over soon.”

“Don’t! Don’t go down there! He’ll get you!” She stops short. Probably lost consciousness again. I can’t help but laugh. The kid is probably too busy pissing his pants to take his mother’s sound advice.

Closing the door behind me, I descend the basement stairs. The steep steps groan under me, and even still, I can hear the kid hyperventilating somewhere in the dark. “Don’t be afraid,” I whisper, gripping my knife. The pressure in my neck is already lifting. The anticipation of what is to come is like a high. I want this kill more than I’ve ever wanted anything.

As I reach the bottom step, I stop. The kid is standing in the middle of the neatly organized

basement. Above his head a single light bulb washes him in a thready light, its long chain dangling so low it brushes against his shoulder.

“Another terrible hiding spot,” I say. “I’m sorry you didn’t do better.”

I glance at the boy. I expect him to be crying, terrified, but he’s looking at me like he feels sorry for me—a slight shake of his head as he holds himself around the waist.

“I’m not playing your game!” I scream at him. I’m so angry they’ve lured me into this—the lights, the running, the resistance. “I make the rules, not you!”

A rustling sounds from the far corner of the dank, dark space. I whip my head to look, half expecting to see someone standing there. “Who’s down here with you?”

The kid doesn’t answer. He doesn’t even turn his head toward the sound, a sound that grows more defined as the seconds tick by—rhythmic, ragged … breathing.

I never encountered a fourth person is this miserable family in all my time watching them. Neighbors stayed away. Even friends and family kept their distance. There is no one else who should be here, and still. I have missed something. I have fucked up somewhere in my planning, and now I will have to adjust course again. Maybe I can make this three kills in one night. That would feed my demons and release this pressure on my neck for a good long time.

I hold my breath and try to quiet the rush of blood in my ears. I hold the knife out in front of me, pointing it into the corner of the room, where the darkness is complete. The dim light of the single bulb does nothing to penetrate the shadows around the edges of the basement, and I’m suddenly overwhelmed by the feeling of eyes on me.

The breathing ebbs, and I wonder if maybe the noises are coming from the boy. I spin around as the noise moves behind me. No, it can’t be him. Fear grips my chest, and the little hairs on the back of my neck stand on end.

Something knocks my arm. The knife goes skittering across the floor, and I stumble back.

Outside, a car door slams. The kid’s mother cries out, and then there is a flurry of footsteps and a man’s voice—the father—from upstairs.

“Somebody broke

in!” Mom screams. “He’s in the basement with Daveed!” More shuffling upstairs.

My arm aches, and as I hold it up in front of me, I realize that when my knife fell to the floor, my hand was still gripping it, having been separated from my wrist so quickly that my brain could not process it. There should be pain, but I cannot comprehend that the ragged, bloody stump belongs to me.

The kid is smiling when I look at him. I want to scream at him for putting me in this position. “What—what is this?” I stammer. “What are you—who—what is this?!”

I stumble to the bottom of the stairs, still numb, still unable to feel the pain I know should be racking my mind and body, but fear has taken over and allows me nothing but dread. The kid’s parents, Mom and Dad, are just standing at the top of the stairs.

“Oh no,” the kid’s father says. He sinks to his knees, his arms hanging loosely at his sides. The mother steps forward and puts her hand, a zip tie still hanging from her wrist, on the doorknob.

They don’t rush me. Their expressions confuse me. Don’t they want to save their son? I glance behind me to see the boy just standing there. He doesn’t go to his parents. A cold, mind-numbing terror washes over me. They won’t come down because they are afraid.

“Daveed, baby?” the mother calls, only the slightest tremble in her voice. “You got your flashlight?”

I look at the boy, unable to speak as grunting and shuffling echo from the shadows.

“Yes, ma’am,” the kid says.

The mother sighs. “Stay in the light, baby.”

I can’t make my legs work. I can’t take a single step. Blood gushes from my wound; flashes of light dance at the edges of my vision. The pain finally announces itself like a clap of thunder. I can’t keep my body from spasming, bending my back until I’m looking at the ceiling from somewhere below my knees. In one terrible moment, the reality of what is happening falls on me: something has a hold of me. Its hands reach out of the shadows like tendrils unfurling. There is no more pressure on my neck. There will be a death, but it will not be this boy or his mother. I glance at him as something vital snaps in my back and my vision blurs from the sudden burst of pain. He reaches up and grasps the chain hanging from the lightbulb over his head. He yanks it down, and the darkness envelops me.

I lay on the floor as the thing from the shadows fills the darkness around me and begins to devour me. It slashes across my belly, spilling its contents

across the cold concrete. The pain comes in like a wave, crashing over me, sucking the scream from my throat, stealing the breath from my lungs.

The last thing I see, before I’m lost to the dark and the tide of pain, is the kid. He’s holding his flashlight over his head, and it shines down on him like a spotlight. He stays in the center of the beam as he ascends the stairs.

He was afraid of the dark, and now I understand why.

I am not the only monster lurking here in the shadows. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...