1

WHAT WE SAVE

I can feel water and I can feel heavy weather on the way. Mother said, “You’re like a dowser, Nonie, like those people who can feel water under the ground and help farmers find it, only you do it with water everywhere.” What she said is so. I can understand water—floods and rivers over their banks, storms and clouds and placid days when the droplets sit in the air like they are thinking quietly of joining the earth.

But the storm that took Amen, that storm I didn’t feel. It was too big. It was the one that broke the floodwalls. That was the last night of the Old City and the museum and Amen and everything that trapped us, when the wide Hudson opened its mouth wider and became the sea and the sea came to us and we took off north, no matter how scared Bix was, no matter how hard it was to leave Mother behind. It was the storm that started something new.

We still lived in the place we called Amen, what had been the American Museum of Natural History. Time made us shorten that name. We said “A-M-N-H,” for the whole place—the ancient rooms we tended, the collections we protected—then “Amen,” when it only meant the village we made on the roof of the museum library, the name a prayer to keep us safe. And we were safe up there a long time, Bix and me and Father and Keller, and Mother—before we lost her—and the rest of us working to save the collections and be there, just be there, saving each other too. I was young then, thirteen, Bix sixteen. I was a blur of closed heart and quiet voice, scared of the dark and of losing home, cozied in a place Mother made for us on the roof, where time and space were as fixed as they could be in The World As It Is.

Father said we would run north to Mother’s land, Tyringham, our taiga, our last safe place, if we lost Amen. We made the go packs and canoe, learned to hunt, worried about the dogs and the Lost, about guns, about how people outside Amen fractured into groups by color, about everything between Amen and Tyringham. We worried about losing Amen.

In the Museum Logbook we kept a list of all that might be lost, everything in the museum. The adults made notations on anthropology, archaeology, geology, paleontology, ichthyology, hydrology, geography, entomology, the museum records no one could read anymore on computers. They made notes from memory or books in the library, from listing the contents of cases and storage drawers and displays. And there was my list, my shadow list. In margins and on back pages, I added drawings and notes on water and how I understood it, the clouds, the shine on a puddle, the animals after they drank, the rainbow over the city, the way to feel the pressure drop for a squall, or the build of a hurricane. I added them to help me remember, and for other people to find one day, if all they found was the book.

The Museum Logbook was to keep understanding alive, the most important work there was for Amen, a race against rot and mold and time to save things, even the memory of things. My Water Logbook was only for the future. I was young then and didn’t know why I was making it. Now I know it was to make the new way of knowing that might put it all right again, the new thing I’m standing at the edge of, here where there is drinkable water and where people are in the rooms of the house writing and cooking, and I’m about to leave again, but only for good reasons, remembering what was left behind in that storm.

My Water Logbook didn’t help me see that storm. I didn’t know what it would bring—the journey and the people who helped and the ones who harmed. That storm, that last storm of Amen, was a hypercane, like Jess predicted, the Monster in the Water. It moved faster than thought and faster than sense. It swept in to take everything, and I didn’t see it. I was a girl on a roof, and I couldn’t tell everyone, “The end is here.”

2 HYPERCANE

Everyone else was asleep on the roof, in tents and structures up there, sweating out the November heat. It was so still; all the air was sucked out of breathing. I couldn’t sleep. I didn’t know why. Something wasn’t right, but I couldn’t feel what. I took the plastic bag out from under my pillow and looked at the photograph inside it, smoothed the bag’s wrinkles out and looked at Mother’s face, not smiling at the camera, but pointed toward a microscope, her profile blurry in the darkness.

Then the air was pulled out of my lungs, the world inhaling before a scream, and a wind hit the longhouse hard. Bix’s body tumbled into mine, face-to-face and staring. I felt Bix breathing, felt her fear, wanted to reach to her, like she was small, and I was small, and we were in the twin bed in the old apartment and Mother was still alive and would lie down with us and brush our hair back and kiss our foreheads and say, “Good morning, my sea butterflies.”

Lightning flashed. “Nonie! Bix!” Father’s voice.

“Allan!” Keller was reaching for gear. The wind scattered all our things.

Bix slipped into big-sister bossing, she almost screamed into my mouth, “Go, Nonie!”

I found shoes and go pack. In my pack I had the Logbook, wrapped in oiled canvas and safe from rain, tucked under my rain shell for extra protection. I felt for it. It was there. I’d kept it with me for months. There was strange weather. There was so much to make note of. It felt safer to have it with me always after Mother died, no chance to lose it in a storm. I shoved the baggie with Mother’s picture in next to it. I felt for my water bottle, the ammonite.

A sound like a giant taking a bite out of the top of a forest echoed overhead, and the roof above me was gone. Shock drained into my blood.

“Run!” Father yelled. I put the pack on my back and ran. Bix and Keller and I reached the longhouse door as the wall poles buckled. We pushed outside. I turned to look as the house crumpled, going down like one of Keller’s shot deer, knees failing under it.

“Run!” Keller shouted.

It only took a second for the place we’d lived for eight years to fall to the hypercane. The storm didn’t care at all. I stood and stared.

“Nonie!” Father called, running for the stairwell, Bix and Keller behind him.

I stood still. I couldn’t remember what to do. I knew I needed to follow, but I watched the storm build behind them. I moved one foot in their direction. I made the seconds small and fast. This was how it was in a night storm. We got up. We got safe. In a bad storm we ran for the museum library below us, the windowless stacks, safe as a thick-walled bunker, dark, mold-smelling and caked in lonely days and nights spent waiting out storms.

I stumbled, followed Father and Keller and Bix through storm-pitched pieces of Amen coming apart, faces of people I loved flashing past, the pressure sinking so fast my teeth itched. Around the broken frame of our house, tarps and poles of other structures collapsed in the gale, people crawled from under on their bellies. Wind moved through Amen, a curious animal, ate up what it found until there wasn’t a thing left to eat. My ears popped. The pressure fell, wind braided and doubled with a funnel cloud forming over the Park, coming our way.

I saw Jess and Beaumont at their hut, she was pulling out a pack, he carried a jug of water, a lantern, his bow. She was carrying baby Evangeline in a sling around her body, stooped over her so the rain wouldn’t hit the baby’s face, compass around her neck. She looked up and saw me. I screamed at her, “The Monster in the Water?!”

“Yes, Nonie!” she yelled back over the storm. “Get to the stacks. I’m right behind you!”

“OK!” The baby worried me. There was so much wind.

“Remember the shark,” she yelled, hoisting the pack onto her shoulder. I remembered what she’d told me. When I was scared and started to disappear into silence and blankness, I could think about how you can hypnotize sharks by rubbing your finger down their snout. It calms them so they don’t panic. When I started to panic and go back to quiet, to hiding, Jess said I could rub the skin between my thumb and forefinger with the fingers of my other hand and I would feel calm, too, and maybe not need to disappear at all. “Go, Nonie! I’ll be right there,” Jess yelled over the wind.

I found speed then, my feet obeying where my mind did not. A downpour of water came, almost too dense for moving, a heart of lightning, random hail, a voice of the wind that shut out thought, and then I was running to catch Bix’s advancing back, chasing her like a ghost through the unknown air.

3 LENINGRAD

Mother was never afraid of the water like Bix was. She was like me, she loved it. She studied sea butterflies—pteropods—at Amen. Mother worked at the museum in The World As It Was. She was the one with keys. She brought us there when the city fell down. We went to the safest place we knew, big old doors and big old locks and lots of other people with keys who walked there through the water one night and stayed on because no one was coming to save anybody.

I was in love with Amen already. When we were small, before things changed, on Sunday afternoons Mother went in to get more hours in the lab and Father walked Bix and me around the dark, still rooms while people we didn’t know looked at the bones and the birds and the beasts. We would lie under the great blue whale, and I would pretend I was under the ocean. It was a place that said time broke everything before and repaired it new. Sometimes new was better and sometimes new was worse. But if there was a change, it would change again. As the broken world turned outside the walls, I longed for the quiet rooms that taught me that.

Mother didn’t like the subway entrance, brought Bix and me in from the street, up the big stairs and to the big doors, right past the statue of Teddy Roosevelt. She catalogued pteropods in a basement lab. The sea butterflies told her everything she needed to know about what was happening to the world, the change of chemistry in the ocean, the things we were doing to break it, the things we might do to make it whole again. It was the only work that mattered, she said, sometimes when she forgot to be humble, and in the joy of walking into the museum. In her voice, there was something else, too—greed, hope. The picture in my plastic baggie used to hang on the fridge in our Tenth Street apartment, her head bent over a microscope, looking at a specimen, mouse-brown hair tied back in a ponytail, long beak nose pointing at the instrument like an arrow. There was another picture of the lab, too. Mother with her arms around another worker when they got a grant, champagne bottle on the table in front of them. That picture was lost in the flood. The World As It Is doesn’t let you keep things, but her body kept that arrow gesture in her bones, her whole life bent toward research, never wavering, even when she couldn’t work like that. She had keys to the kingdom. She won them herself. She gave the museum to Bix and me.

By the night of the storm that took it, Amen only had a few people left, all too scared or stuck to take the walk north, sleeping on the roof in lean-tos and made-up structures. Used to be only tents there, then the rule was if you stayed, you built solid. The roof was the only way to survive the rotting city, the people who might break a window and get into Amen until they saw there was nothing that would feed them. We were high on the roof, safe from people with guns or dogs, the old building rotting and dangerous below. Shelters kept the rain off, fought the heat. We had a garden in the Park. When we went, we carried the two guns we had left, the ammo we saved, the ones who knew how carried bows we made or scavenged. We grew food. We had bees. We went out. We came back. When we were lucky, the empty city echoed around us, dog packs off hunting deer. The longer we were in Amen, the luckier we got, the quieter it was, a whole city moved off to find good water.

We were like the people in Leningrad, Father said, in the War, the Second one, when the Hermitage, a museum bigger than ours even, was left for dead in a dying city but the curators stayed. There wasn’t much left, but in Leningrad in the siege in the War the curators stayed and ate restorer paste to stay alive and wrapped the dead and laid them in the basement until the thaw and chipped the ice off the paintings while the siege went on outside. All that mattered was that the art remained. Even if they could have run away across Lake Ladoga and into the edges of the taiga forest and hidden with what they knew, they wouldn’t have left. They belonged to the art and the art belonged to them and it was a sacred duty. But so was the vision of what it would be one day when the siege was over and the windows replaced and the broken walls repaired and the museum alive again for everyone, for the world that mattered, the one they wanted.

That was us. Only the siege was storms. We stayed because we had to, because Bix was too terrified of the water to go, but we also stayed because it was the work, Mother’s and Father’s work, the reason they met, the work of keeping what was left until the world was ready again.

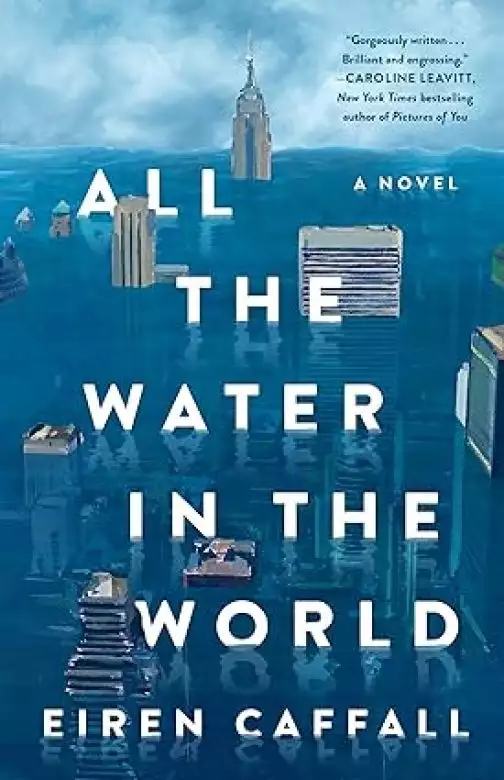

Copyright © 2024 by Eiren Caffall

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved