One

“Hon. Morgan is missing.”

That’s how Dad put it when he called. I’d been in the passenger seat, trying to recover from my airplane nerves, wishing my mom would drive a little faster, when my phone buzzed in the cup holder.

Good thing I wasn’t driving. Mom and I were both tired after the early-morning flight back to New Hampshire. I had offered to drive home from the airport, but we both knew I was still too rattled to be operating a car.

“Missing . . . like missing missing?” I asked. I tend not to be very eloquent when I’m anxious. And Dad has a way of overdramatizing things, so I wanted to clarify.

“Umm . . . yes . . . missing,” Dad said. “But don’t panic, Ivy. It’s only since last night. It hasn’t even been twenty-four hours. The police are on it. Everyone’s on it. Including me. But you know, Morgan probably just went off with a friend or a boyfriend and forgot to let her mom know.”

That didn’t sound like Morgan at all. Morgan is usually pretty careful about not stressing out her mom, since she’s raising Morgan and her brother on her own. Morgan is thoughtful, considerate, compassionate. Parents and teachers have been using these adjectives about her since we were twelve.

My heart started racing, and I started chewing the drawstring of my peasant top.

“So . . . any texts from her?” Dad asked. “That’s why I’m calling. I told her mom I’d ask you. I tried to call earlier, but I guess it didn’t go through because you were on the plane.”

“Oh.” Now I felt even worse. I know that cell phones often work on flights, but I always turn mine off to minimize any chance of inadvertently helping my flight crash.

“So, hon. Did you hear the question? Any texts or other contact from Morgan in the last day or so?”

“No,” I said softly.

The truth was I hadn’t heard from Morgan in three days. And I had been counting.

We’d never gone this long without talking or at least texting. It wasn’t like she couldn’t text while working at Dad’s amusement park, but when she’d stopped replying to my messages on Wednesday, I’d tried calling her. When she didn’t pick up for two days, I’d given up, reluctantly figuring we’d reconnect when I got home.

“Okay, too bad. I’ll let them all know. And try not to worry. There’s a lot of great people working on this. You know I know the deputy chief, right? I’ve already had a little chat with him about how important this is.” My dad was talking fast, but he finally stopped for a breath. “I’ll let you know if I hear anything else,” he added. “How far are you from home?”

“About an hour away,” I said, eyeing the speedometer. “Maybe a little more.”

“Okay. I’m just pulling into Fabuland now. Talk soon. Bye, Ivy.”

“Bye,” I mumbled, but he had already ended the call.

I was silent for a moment. Then I drew in a breath, feeling my mom’s attention more on me than the road.

“So--” I began.

“I heard everything your father was saying,” Mom said, sighing. “Of course Ed knows the deputy chief. And he still talks pretty loud on the phone.”

She stiffened right after she said it, as if remembering that this was a really terrible time to drop subtle criticisms of one’s ex-husband.

“I’m so sorry, Ivy.” Her hands clenched the steering wheel. “But let’s sit tight and wait for more news. I think with everything that’s happened, Morgan probably just needed some time to herself.”

Time to herself? That didn’t sound right either. Yes, this had surely been the worst week of her life. But up until three days ago, she had been willing to accept comfort from others. From me.

I stared out the passenger-side window, watching the trees whip by as my mom reluctantly passed a rattling pickup truck plastered with bumper stickers from elections that preceded my birth.

To my silence, Mom added, “It’s been an exhausting, emotional week for so many people. Let’s not jump to any conclusions. She may just have needed some space for a night.”

An awful, insane week, more like. And even that was putting it mildly.

“Yeah,” I murmured, so Mom would know I had heard her. Then I scrunched down in my seat and started fiddling with my phone, going over my texts from the last ten days.

It had all started last Friday.

I’d been gone only a few days--to North Carolina with my mom, visiting my grandparents, like we do at the beginning of almost every summer--except my older brother had weaseled out of it this year because of a summer job he had gotten at Syracuse. I’d slept late that morning, waking up to two missed calls and that first terrible text from Morgan:

Ivy are you there? Something bad happened.

Of course I’d called her right back. She wasn’t at work. She was home, still crying. I could barely believe it when she told me through sobs. I spent the next couple of days saying, It’s okay, Morgan. It’s okay, into the phone. She let me keep saying it even though we both knew it wasn’t really true.

Since I was so far from home, it hadn’t felt real until Morgan sent me the link to the first news story that broke. I had it bookmarked on my phone.

East County Herald

Saturday, July 1

Danville Mourns Ethan Lavoie

On the night of Thursday, June 29, in Danville, Ethan Lavoie, 19, is believed to have fallen to his death from the train trestle in Brewer’s Creek Park.

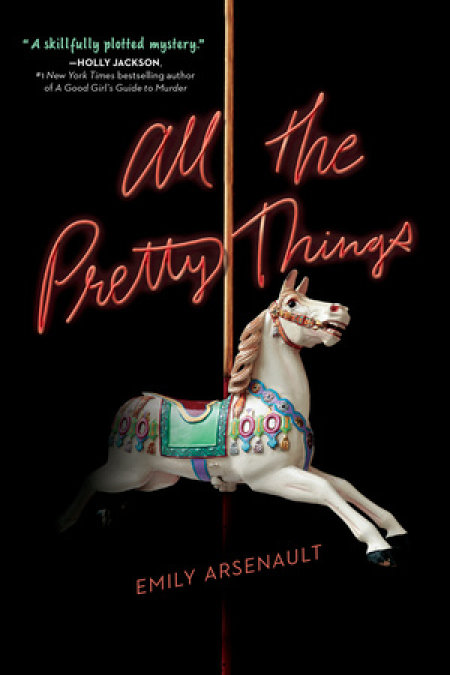

Ethan, who had Down syndrome, was well known in the close-knit community. He was a recent graduate of Danville High School, where he had been a member of the track team. He worked at Cork’s Doughnut Dynasty in the maintenance department for three years, before recently switching jobs to the maintenance department at the Fabuland amusement park, also owned by Edward Cork.

“He was very excited to work at the park,” said Steven Jeffries, Lavoie’s uncle, at an informal gathering in the Lavoies’ High Street yard late Friday evening. “He loved going to Fabuland and he couldn’t wait to take his family there now that he had an employee pass. He loved the merry-go-round and especially the food. Pepperoni pizza was his favorite.”

It’s unclear why Lavoie was on the trestle alone. He was usually accompanied by a friend or family member when he walked to or from work.

“He almost always had a buddy walking him because that was his mom’s rule. He knew he wasn’t supposed to walk through Brewer’s Creek Park by himself, especially at night. I don’t know what got into him,” said Mr. Jeffries tearfully. “Maybe he just forgot.”

Residents--particularly young residents--of the Wilder Hill neighborhood and nearby Rowan Village mobile community, where the Lavoies reside, frequently cut through Brewer’s Creek Park when bound for Fabuland because the street route is significantly longer.

Morgan Froggett, 16, took the shortcut while walking to her job at Fabuland Friday morning, when she spotted Ethan lying in the creek bed below. Ms. Froggett attempted to revive him before calling for help. Emergency personnel arrived at the scene within minutes, but Lavoie had already succumbed to his injuries and was declared dead at the scene. Ms. Froggett was interviewed by authorities. As of publication, Ms. Froggett’s mother has declined a request for comment on her behalf.

Mr. Cork has set up a GoFundMe to help the Lavoie family with funeral expenses. Mr. Cork donated an initial $1,200 and has pledged to match any additional donations made. The funeral service has not yet been scheduled at the time of printing.

For more information, go to Ethansfundbeam.com or call Chris Nealy at 603-555-0989.

Since that Friday, Dad and Morgan had been giving me daily reports. Dad talked about the police coming and going at Fabuland throughout the week, asking everyone questions. By the end of the week, he seemed frustrated that they were asking the same things, distracting and upsetting his employees. Morgan mostly talked about the funeral, which happened July 5. There were a few hundred guests and the youth choir from Ethan’s church sang. Morgan never wanted to talk directly about finding Ethan, though, and I didn’t ask her to. She talked a little bit about what she knew--what everybody knew--about his last night at Fabuland. He’d ridden the Laser Coaster with Briony Simpson, Lucas Andries, and Anna Henry. He’d told them that he was calling his mom for a ride home. But then apparently he hadn’t. He’d walked home alone, cutting through the woodsy Brewer’s Creek area as all the kids without regular access to a car often did. And, while crossing the trestle, he’d fallen to his death. Nobody knew exactly what had happened, or why he didn’t call his mom. Usually one of his cousins--Winnie or Tim Malloy--walked or drove him home, but neither of them had been working at Fabuland that night. When the police opened Ethan’s locker, they found his backpack in it.

Morgan had reported sadly that everyone was beginning to accept the police’s preliminary conclusions. That it was dark, and Ethan had lost his footing and fallen. He might have still been dizzy from riding the coaster, although the kids who’d ridden it with him said they’d seen no sign of that. And his backpack was probably in his locker because he’d had trouble with the lock--he’d had trouble in the past; the old ones get sticky. By Monday, Morgan was able to talk and text about other things--although a little tentatively, a little half-heartedly. She talked about maybe getting a haircut. And I finally got her to laugh, telling her a story about the little snake in my grandparents’ pool--my mom wildly Googling how to get a snake out of a pool on her phone while my grandpa bumbled around with a net, cursing and trying to scoop it out.

On Wednesday afternoon, while I was at the grocery store with my grandma, trying to help her choose between two seemingly identical rotisserie chickens, my phone buzzed with a text from Morgan.

Want to talk to you about something I saw the day I found Ethan.

Unsettled by the vagueness of “something,” and surprised she suddenly wanted to talk about that day specifically, I’d made my way to another aisle to call her. Morgan hadn’t picked up but immediately sent me a text saying that she would call me later, after work.

She didn’t.

I waited and waited until I couldn’t stand it any longer. I texted her at eight p.m. that night, well past when she would have gotten home from the park and had dinner. No response. I called her at nine and texted her again. And again the next morning.

But now this. My best friend was missing.

Since last night?

Things must have been really bad. Morgan would never stay out all night without telling her mom where she was going. This had to be worse than my dad was willing to say.

I could feel Mom’s gaze on me as I tried to process all this. I turned away, curling into the passenger-side door. She couldn’t hide the worry in her eyes. Or the relief that it wasn’t me who was missing. I know she can’t help it. Whenever she hears about something bad happening to another kid, she looks at me that way.

Maybe someone had abducted Morgan. Maybe someone had killed her. Maybe she was trapped somewhere, trying to escape. Maybe she’d told the wrong person about the “something” she had been about to tell me?

My head buzzed with--and then hurt from--the possibilities. After about a half hour of turning them over, I thought I might scream, or explode.

Instead, I rolled down the car window for some air. That was a start.

No sooner had I cracked the window open than my phone rang again. “Dad Cell” flashed across the screen. I fumbled to swipe the screen, my fingers clumsy with nerves.

“Dad?” I croaked into the phone.

“Ivy! Good news. They found her.”

I took a breath, feeling some of the tension and fear of the last half hour drain away as I exhaled.

“Who?” I said.

I meant who was the they that found her, but Dad yelped back before I could correct myself. “Morgan, Ivy. MORGAN. Wake up, sweetheart. Who else? How far are you from Fabuland now?”

“Umm . . .” I looked at the GPS. “About twenty minutes now. Is she okay?”

“Come right to the park,” he demanded. “It looks like we could use your help.”

Two

Turns out that when the first workers arrived at Fabuland, a sharp-eyed ride operator had noticed movement near the top of the Ferris wheel. It was Morgan. She was up there by herself. She didn’t seem hurt, but when they tried to run the ride to get her down, she leaned far over the safety bar and screamed. They were afraid she’d totally lost it and might jump.

My dad had called the cops and they had suggested using the big blue cherry picker--the one we use to fix the rides--to send someone up to talk to her. A police officer and Morgan’s mom tried, but whenever they got close, Morgan would scream and jostle the gondola.

“Ivy’s her best friend,” my dad was saying to the cops when I arrived. He motioned for me to join the conversation at the ride controls. “She’s great. She’ll know how to talk to her. Believe me.”

It took me a second to realize he was suggesting I go up. He repeated these words until the skepticism fell from the officers’ faces. Dad is very convincing. Never mind that I’m more scared of heights than anything else I can think of. That’s why I never go on most of the rides. But this was different. The terrified look on Morgan’s mom’s face made it clear--I had to do this.

I got in the cage with the policeman and he secured its swinging door with a heavy metal latch. The cherry picker’s engine made a sickly metallic hum as it started to lift our little cage. My stomach did a flip and I grasped the handrail tighter. You were thirty thousand feet up this morning, I tried to tell myself. You survived that, you can survive this.

Everyone was staring at me and I felt like a princess about to be fed to a dragon. The vibration of the tired machinery rattled my teeth. I gripped the side of the cage and stared at the police officer’s dark-blue shoulder so I would not have to watch us leave the ground. My heart thudded as we approached Morgan’s gondola.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved