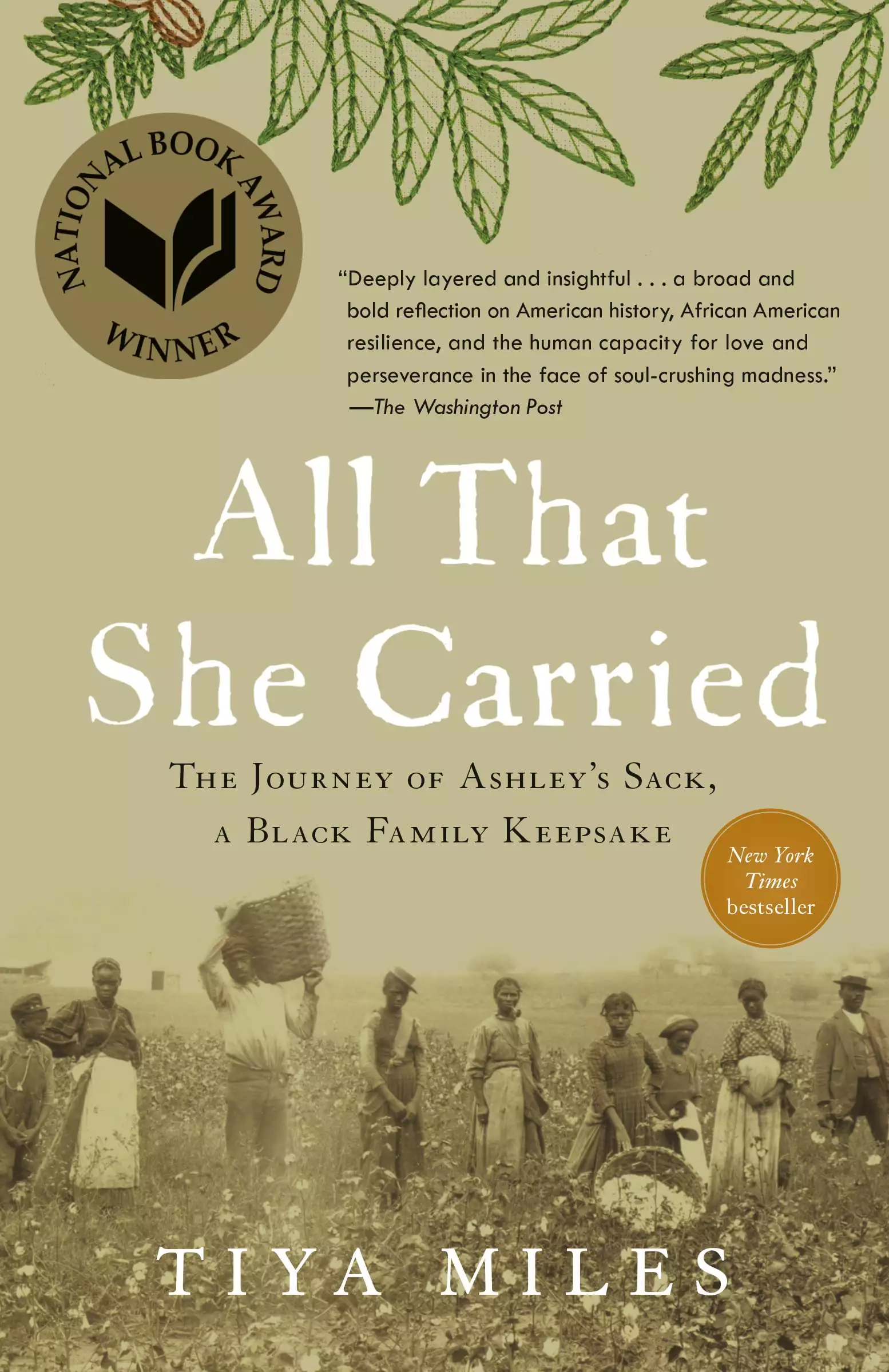

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley's Sack, a Black Family Keepsake

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

WINNER: Frederick Douglass Book Prize, Harriet Tubman Prize, PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award, Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, Lawrence W. Levine Award, Darlene Clark Hine Award, Cundill History Prize, Joan Kelly Memorial Prize, Massachusetts Book Award

ONE OF THE TEN BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: The Washington Post, Slate, Vulture, Publishers Weekly

“A history told with brilliance and tenderness and fearlessness.”—Jill Lepore, author of These Truths: A History of the United States

In 1850s South Carolina, an enslaved woman named Rose faced a crisis: the imminent sale of her daughter Ashley. Thinking quickly, she packed a cotton bag for her with a few items, and, soon after, the nine-year-old girl was separated from her mother and sold. Decades later, Ashley’s granddaughter Ruth embroidered this family history on the sack in spare, haunting language.

Historian Tiya Miles carefully traces these women’s faint presence in archival records, and, where archives fall short, she turns to objects, art, and the environment to write a singular history of the experience of slavery, and the uncertain freedom afterward, in the United States. All That She Carried is a poignant story of resilience and love passed down against steep odds. It honors the creativity and resourcefulness of people who preserved family ties when official systems refused to do so, and it serves as a visionary illustration of how to reconstruct and recount their stories today.

FINALIST: MAAH Stone Book Award, Kirkus Prize, Mark Lynton History Prize, Chatauqua Prize, Women’s Prize

ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: The New York Times, NPR, Time, The Boston Globe, The Atlantic, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Smithsonian Magazine, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Ms. magazine, Book Riot, Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, Booklist

Release date: June 8, 2021

Publisher: Random House

Print pages: 377

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley's Sack, a Black Family Keepsake

Tiya Miles

PROLOGUE:EMERGENCY PACKS

I think we should make emergency packs—grab and run packs—in case we need to get out of here in a hurry.

—Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower, 1993

Rose was in existential distress that fateful winter when her would-be earthly master, Robert Martin, passed away. The place: coastal South Carolina; the year: 1852. We do not know Rose’s family name, or the place of her birth, or the year of her death. Such is the case with the vast majority of African and Indigenous American women who were bought, sold, and exploited by the hundreds of thousands. But we can be sure that Rose faced the deep kind of trouble that no one in our present time knows and only an enslaved woman has seen. Rose knew that she or her little girl, Ashley, could be next on the auction block, the cold device enslavers turned to when their finances faltered.

Ripping families apart was a common practice in a society structured by—and, indeed, dependent on—the legalized captivity of people deemed inferior. And sale could not have been the end of Rose’s worries or the worst of her fears. She must have dreaded what could occur during this relocation and after: the physical cruelty, sexual assault, malnourishment, mental splintering, and even death that was the lot of so many young women deemed slaves. Rose and Ashley’s life together, already encased by swales of suffering, could be torn asunder in a matter of moments with the stroke of a pen. Their lives apart portended even worse without the bonds of family. Rose adored this daughter and desperately sought to keep her safe. But what could safety possibly mean in a place, at a time, when a girl not yet ten years old could be lawfully caged and bartered? What would Rose do to protect her child? What could she do as an unfree woman with no social standing, political power, economic means, or cultural currency positioned in the trenches of unpredictable and insurmountable difficulty?

The kind of fix Rose was in—life-threatening and soul-stealing—was one that Black women like her had continually encountered over more than two centuries of life in America. It was a fix articulated by the few enslaved women who managed to escape and tell their stories in the nineteenth century and, later, by Black women thinkers and artists who drew sustenance from the writings of these cultural ancestors in the generations that followed, including our own. How does a person treated like chattel express and enact a human ethic? What does an individual who is deeply devalued insist upon as her set of values? How does a woman demeaned and cowed face the abyss and still give love? Rose’s actions, outlined in a single and unusual text and barely preserved for history, give us a sense. When the auction block loomed on her little family’s horizon, Rose gathered all of her resources—material, emotional, and spiritual—and packed an emergency kit for the future. She gave that bag to her daughter, Ashley, who carried it and passed it down across the generations.

Rose possessed inner strength and creativity even as calamity struck. Saving another’s life meant acting despite despair, and she dreamed up means of survival as well as spiritual sustenance.1 Surely Rose felt that what she did was far too little, much too late. Surely she feared that a battered bag would not matter enough in the end. But Rose pressed on, matching the mettle of an entrenched slave society with a glimmering will of her own. And although we cannot know exactly how events unfolded, we can conclude that Rose’s gift did affect her descendants’ lives, no matter how inconsequential her act of packing may have felt in the moment. For, three generations later, a great-granddaughter of hers, Ruth Middleton, created a remarkable “written” record attesting to Rose’s deed. Ruth’s chronicle is evidence of a long-term effect that Rose herself would never see: her female line would continue against all odds, and her will to love would be carried forward.

Rose couldn’t know how things would turn out, but she held fast to a vision. She saw her daughter alive and provided for her into the future, a radical imagining for a Black mother in the 1850s. Rose’s daughter

Ashley, realized that vision by surviving, and her great-granddaughter, Ruth, preserved their history by stitching sentences onto the surface of the sack. In the third decade of the twenty-first century, we face our own societal demons, equal in some respects to the system of slavery that would finally be slayed. The world feels dark to us, just as it must have for Rose, and like Rose, we can’t know what will happen. We think it a fantasy that we might rescue our children’s futures, or revive our democratic principles, or redeem our damaged earth. In our moment of bleak extremity, Black women of the past can be our teachers. Who better to show us how to act when hope for the future is under threat than a mother like Rose—or an entire caste of enslaved, brave women who were nothing and had nothing by the dominant standards of their time yet managed to save whom and what they loved? Rose and her long line of descendants realized that salvation depended on bearing up to the weight and promise of their baggage. We should, too.

Just as Rose and Ashley found on their forced journeys through slavery’s landscape, there is no safe place of escape left for us. The walls of the world are closing in. We need to get out of here in a hurry. We need to get out of these frames of mind and states of emotion that elevate mastery over compassion, division over connection, and greed over care, separating us one from another and locking us in. Our only options in this predicament, this state of political and planetary emergency, are to act as first responders or die not trying. We are the ancestors of our descendants. They are the generations we’ve made. With a “radical hope” for their survival, what will we pack into their sacks?2

INTRODUCTION

LOVE’S PRACTITIONERS

In African American life black women have been love’s practitioners.

—bell hooks, Salvation: Black People and Love, 2001

We forget that love is revolutionary. The word, cute and overused in American culture, can feel devoid of spirit, a dead letter suitable only for easy exchange on social media platforms. But love does carry profound meanings. It indicates the radical realignment of social life. To love is to turn away from the prioritization of the ego or even one’s particular party or tribe, to give of oneself for another, to transfigure the narrow “I” into the expansive “you” or “we.” This four-letter word asks of us, then, one of the most difficult tasks in life: decentering the self for the good of another. This is a task for which we need exemplars, especially in our divisive times. Here in these pages, we take up a quiet story of transformative love lived and told by ordinary African American women—Rose, Ashley, and Ruth—whose lives spanned the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, slavery and freedom, the South and the North. Their love story is one of sacrifice, suffering, lament, and the rescue of a tested but resilient family lineage.

By loving, Rose refused to accept the tenets of her time: that people could be treated as property, that wealth was a greater value than honor, that some lives had no worth beyond capital and gain. Hers is just one telling example of refusal from the collective experience of enslaved Black women, who practiced love and preserved life when all hope seemed lost. Even when she relinquished her daughter to the slave trade against her will, Rose insisted on love. Despite and during their separation, Rose’s value of love prevailed. The emotional bond between mother and daughter held longevity and elasticity, traversing the final decade of chattel slavery, the chaos of the Civil War, and the red dawn of emancipation before finding new expression in the early twentieth century just as a baby girl, the fifth generation of Rose’s lineage, Ashley’s great-granddaughter, was born.

Just as remarkable as this story of women who dared to insist on love is how we have come to know about it. Rose’s testament, as told by Ruth, is preserved on an antique sack that once held grain or seeds. Traces of the abused and adored, the devalued and the salvaged, the lost and the found accrue in this one-of-a-kind object. A mother bears the sacrifice of her daughter; a daughter carries on amid unspeakable loss; a descendant heaves the harrowing tale into the twentieth century; and we have the chance to be the better for its arrival here on our doorstep. Through the medium of the sack, we glimpse the visionary fortitude of enslaved Black mothers, the miraculous love Black women bore for kin, the insistence on radical humanization that Black women carried for the nation, and the immeasurable value of material culture to the histories of the marginalized. Although Black women have been treated like “the mules of the world,” in the words of writer Zora Neale Hurston, this sack bears them up as at times exemplifying, to borrow Abraham Lincoln’s phrase on the precipice of the Civil War

the “better angels of our nature.”1

Ruth Middleton, a lineal descendant of Rose, embroidered the lines that follow on what Ruth identified as the original cotton sack Rose packed.

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

With these words a granddaughter, mother, sewer, and storyteller imbued a piece of fabric with all the drama and pathos of ancient tapestries depicting the deeds of queens and goddesses. She preserved the memory of her foremothers and also venerated these women, shaping their image for the next generations. Without Ruth, there would be no record. Without her record, there would be no history. Ruth’s act of creation mirrored that of her great-grandmother Rose. Through her embroidery, Ruth ensured that the valiance of discounted women would be recalled and embraced as a treasured inheritance.

The stained antique fabric once grasped in Ruth Middleton’s hands now hangs in an underground case at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), in Washington, D.C. The artifact, which is on loan from its current institutional owner, the Middleton Place Foundation in Charleston, South Carolina, immediately takes hold of those who view it. Ruth’s intellectual work of interpreting Rose and Ashley’s story and her handiwork in stitching it onto the sack in color produce a composite object of arresting visual and emotional impact. A testament to the national past fashioned of many thinning threads, it has an effect subtler yet more moving than the stone monuments built for pro-slavery statesmen and Confederate generals that have been widely contested in recent years. Those memorials, erected to bury a nation’s sin, were made to be larger than life to command a presence in national memory. At the same time, though, Confederate monuments undermined the aspirational principles of America’s founding: freedom, equality, and democracy. Ashley’s sack makes no such pretense to vainglory. It does not have to. A quiet assertion of the right to life, liberty, and beauty even for those at the bottom, the sack stands in eloquent defense of the country’s ideals by indicting its failures.

The sack crystallizes the drama of a region and a nation torn apart by the moral crisis of human sale and forced separation. But it also possesses a quality so tangibly intimate and personal that it filters a light of remembrance on the viewer’s own familial bonds, leading any of us to ask what things our own families possess that connect us to our past and to wonder what we might gain from the contemplation of that connection. Such is the capacious nature of Ashley’s sack that it can call hearts to attention while also speaking to local, regional, and national histories. Although the bag’s material contents have long been lost, its essential provision—love of a mother for her daughter—still remains. Every turn in the sack’s use—from its packing in the 1850s, to its tending across the dawn of a century, to its embroidering in the 1920s—reveals a family endowment that stands as an alternative to the callous capitalism bred in slavery. In the face of the base commercialization of their own bodies, these Black kinswomen cared for one another, preserving the next generations by

provisioning their perseverance and remembering the past generations who defended their right to life. As the women in Rose’s lineage carried the sack through the decades, the sack itself bore memories of bondage and bravery, genius and generosity, longevity and love.

My own grandmother’s voice travels across warm breezes on a hilly side street in Cincinnati, Ohio. I am nine years old, or twelve and a half, or twenty-one.

“Lord only knows what we woulda done if she hadn’t saved that cow.”

Grandmother has told this story countless times to me, her rapt audience of one, and to other women relatives in private moments over the years. Her dark eyes peer at me with the light of love behind her oversized men’s glasses, the sort that come cheapest with her Medicare plan. She does not need glamour or fanfare. The red brick porch of the Craftsman cottage is her stage. She sits on her lounger with the metal frame, its pillows changed out many times and now mismatched in shape and pattern. Her skin is the honey of bees’ combs, soft as crepe and just as creased. Her hair is a wreath of pressed cotton, once black, now white. A sleeveless, pale blue shift drapes to her calves, exposing ankles swollen from a lifetime of domestic labor in others’ homes and agricultural labor on others’ farms. She leans back and folds her hands across the broad moon of her belly, which birthed six babies in Mississippi and seven more in Ohio. In the summertime, she keeps a cool drink on the ledge of the porch wall—lemonade or sun tea sealed in a Mason jar. She reaches for the cooling liquid, wets her lips, and continues. She is my first storyteller, the one who tends me when I am sick, the one who bakes my favorite rice pudding. She is my beloved.

“If it wasn’t for my sister Margaret,” my grandmother preaches, “we woulda had nothin’ left.”

This was the defining story of my grandmother’s childhood in Mississippi. It told of a fragile family and a brave Black girl. My maternal grandmother, Alice Aliene, was born in Lee County to a mother much younger than her father. Her father, Price, was tall as an oak, with bark-dark skin. He had “eyes like an eagle’s,” to hear my grandmother tell it, which she claimed he got from a “half-Indian parent.” Price had been born into slavery’s last days. He told my grandmother, and she told me, that he had been sold away from his mother. Maybe this is why the 1870 federal census lists Price as an

eight-year-old alone, with no guardian or family.My grandmother’s mother, Ida Belle, was the yin to Price’s yang, youthful, light-skinned, with long raven hair “swinging down her back.” This mother, romanticized in the adoration of my grandmother’s words, had somehow come from means. Ida Belle had been born in St. Louis; she could read and write; she could figure with numbers. Ida Belle’s father was white and unnamed in my grandmother’s stories. Ida Belle’s mother had had no choice about this intimacy. “When those white men wanted to go with you,” my grandmother explained to me, “you went.” Ida Belle had a bit of money, a set of gold-edged plates (now in my mother’s display case), and even twenty-five acres of land in her possession. Price, Ida Belle, and their splitting-the-seams farm family of nine were getting by in rural Mississippi, the state that had harbored the worst forms of torturous, Cotton Belt slavery and would later see the gruesome murders of three civil rights workers in 1964’s Freedom Summer. They farmed 165 acres, produced between 25 and 30 bales of cotton per year, and made around $100 to $125 per bale. They had “plenty to eat” back in the 1920s, my grandmother said, and lived “comfortable” on their land. She remembered their white house with the big hallway, long porch with a double swing, “fifteen to twenty head of cows,” glossy green vegetable garden, and fruit cobblers cooling in the kitchen.

And then the family fell into debt, owing someone around fifty or sixty dollars. White men came from town, riding on horses. They appeared armed with papers that they insisted Price must sign. This was a trap. While Ida Belle could have read the contract, Price had never been educated. My grandmother inserts this detail into the story as if it might have made a difference, as if Ida Belle might have marched down to that road in a long skirt and flour-sack apron, ferreted out the secret intention, and prevented the family’s financial downfall. But I know after twenty-five years of studying Black women’s history, and my grandmother must have known from experience as she told me the story back then, that a Black woman was better off hidden than smart when white men came calling in pre–civil rights Mississippi. “I remember seeing her standing on the porch crying,” my grandmother said of her mother. Price signed the documents with his X. Weeks later, the men returned, claiming that Price had relinquished the farm. Who knows what the black marks on those papers really conveyed? The truth became irrelevant the moment those men returned with guns.

My grandmother’s words pick up speed and seem to chase each other now as she tells the story, or maybe it is my memory that blurs the details. All is panic. Who runs to hide? Who stands by as witness? Price

argues with the men. Ida Belle flies to locate her young ones. The children cower. The dogs warn. The family evacuates as alarm evolves into knowing fear.They were being evicted by the Law of the South, which is to say by white supremacist whimsy. They had little time to think or plan, to collect and pack their necessities. They grabbed at dishes, blankets, clothing but lost all of their wealth, which was the land itself, the farmhouse, and the livestock. The men took the family’s cows, which had belonged to Ida Belle. “I never will forget them, in the wagon with the horses, going on down the road,” my grandmother told me. But my grandmother’s sister Margaret, she was shrewd and she was quick. While commotion raged at the front door, Margaret slipped out the back, fetched a cow from the pasture, and led it over to the farm of Old Man Rose. He helped them, later allowing the family to rent one of his houses. My grandmother never mentioned his race.2

That cow was the only thing of significant value rescued from my ancestors’ farm besides their lives. The expulsion drove my grandmother’s family into poverty. This poverty, this pressure, this unrelenting fear of loss would later push my grandmother to marry young and migrate, out of the jaws of the Jim Crow South and into the teeth of the segregated North. But the act of strength and daring shown by Margaret that day enriched them in spirit despite their woes. This is how I remember my grandmother telling it. My great-aunt Margaret, only a teen, saved the day. And my grandmother wrapped the moment up in a silk sleeve of artful story.

I never had the chance to meet this dauntless aunt. I have never even glimpsed a picture of her. But I had seen and touched and admired the work of her hands, a connection just as powerful. My grandmother kept a quilt in her bedroom that Margaret had stitched sometime after the ouster. The quilt bears an appliqué fan design: rose and mint-colored circles and ovals alternating with a regularity broken only by shifts in shade. The backing has cobalt and powder-blue polka dots on a vanilla-cream background that brings to mind the sweet smells of an ice cream parlor. Margaret had folded a blue-dot border onto the edges of the appliqué side, mixing the mild pastel fans with an altogether different feel that smacked of modernist dots and splotches. She imposed what did not fit onto her visual canvas, the mark of a creative soul as well

as a rebel. This girl,

whom I would never know except through stories handed down, was both a maker and a savior. She is remembered in family lore in a way that reflects regional history tinged by archetypal myth.

I inherited my great-aunt’s quilt when my grandmother passed away, more than fifteen years ago. The quilt was for my grandmother, and is for me, a treasured textile. It seems to have absorbed into its fibers the intangible essence of a past time. When I gaze at the vibrant colors of this quilt (including stains of an ancestor’s blood), I see my grandmother as a girl and imagine the faces of her kin. I feel each syllable of that many-eyed monster, Mississippi—a place where heat, terror, and love intertwined. The story of Margaret saving the cow fused with the quilt’s material. The most traumatic event of my grandmother’s childhood is embedded in it. The history of Africans in America is brutal, but we have made art out of pain, sustaining our spirits with sunbursts of beauty, teaching ourselves how to rise the next day.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...