- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

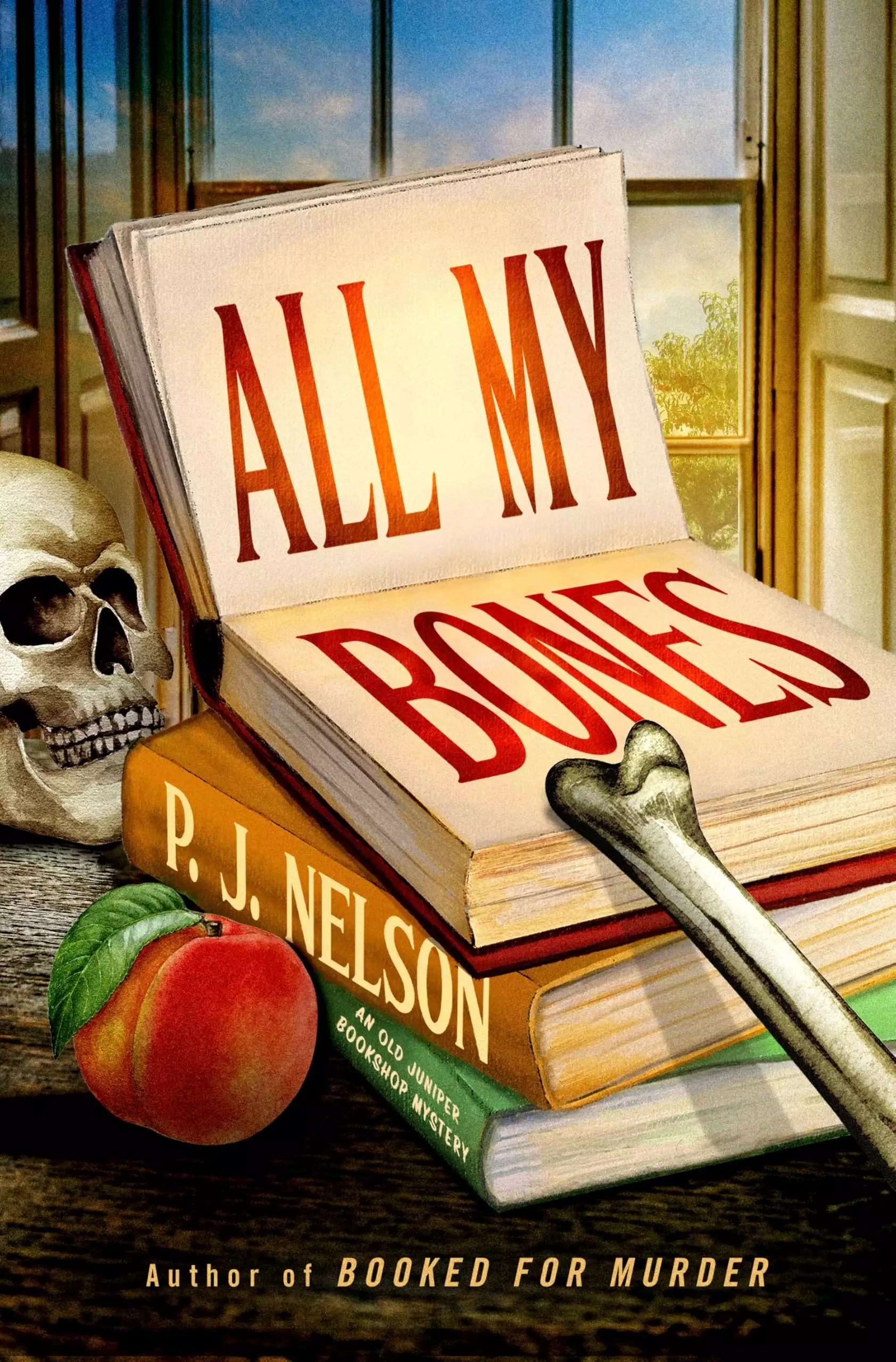

Madeline Brimley, new owner of a bookstore in a small Georgia town, finds herself playing sleuth when a friend is charged with the murder of a much-disliked woman.

Madeline Brimley recently inherited a bookstore in Enigma, Georgia, is embarking on her second career, after her first one (acting) founders upon the metaphorical rocks. Settling in, Madeline recruits her friend Gloria Coleman, the local Episcopal priest, to help her plant azaleas in the front yard of the old Victorian that houses the bookstore. Turning the soil, however, uncovers the body of one Beatrice Glassie, a troublesome woman who has been missing for the past six months.

When her friend Gloria is arrested for the murder, Madeline is determined to prove her innocence and, as she quickly finds out, there aren't many people in town who hadn't wanted to kill Bea Glassie at one point or another. And the very expensive and rare first edition of a particular volume of Grimm's Fairy Tales—ordered by the victim and her sister is somehow tied to the grim death. With the help of her not-quite-boyfriend, a local lawman, and her deceased aunt's bestfriend, Madeline plans to set a trap to catch the real murderer—before she becomes the next victim.

Release date: December 2, 2025

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 352

Reader says this book is...: entertaining story (1) escapist/easy read (1) witty (1)

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

All My Bones

P. J. Nelson

1

APRIL, DESPITE WHAT T. S. Eliot may have told you, is not the cruelest month, at least not in Enigma, Georgia. Azaleas are everywhere, evening skies are Parrish blue, and on the first day of that month in our little town, everyone is a fool.

I’d been back home in Enigma for nearly six months. Settled in nicely, running the Old Juniper Bookshop left to me by my aunt Rose, I was just beginning to feel at home. And why not? The shop was doing remarkably well for a place that sold books. A small group of students from the local college thought of me as some sort of weird guru. And a certain David Madison, gardener extraordinaire, had asked me to dinner a full seven times. Which was seven more times than anyone in Atlanta had asked me out during the last six months I’d lived there.

My aunt, who was not my aunt, Dr. Philomena Waldrop, head of the psychology department at the aforementioned Barnsley College, had, at last, gotten out of Whispering Pines, a very private psychiatric care facility hidden away on Sapelo Island. And while she understood what a cliché it was for a psychiatrist to need a stay in a looney bin—her phrase, not mine—she wore it well. She seemed to be on a much more even keel than she had been six months before when she’d set fire to the gazebo behind the bookshop.

In short, all was well in my blue heaven. Or so I thought.

It was Sunday morning, the quietest day of my week. I slept in, then I waded out of my dreams, down my stairs, and into my kitchen. I took my coffee, French press and all, to the lovely new gazebo that David Madison had rebuilt. I watched a rabbit nibble my parsley and was glad to share it with her. And by the time my cup was empty, there was Gloria Coleman, the feistiest Episcopal priest in the Southeast, rounding the corner of the house and headed my way.

“You can get yourself out of bed and into that gazebo but you can’t make it to a ten o’clock Mass?” she called out.

“I can’t come to your church in my pajamas,” I said, “whereas the gazebo doesn’t seem to care.”

I lifted the French press in her direction, and she nodded. I poured her a cup.

“You missed a really, really good sermon,” she told me, taking the cup and sitting right next to me.

Gloria was a surreal bit of adventure even when she was sitting still. She looked more like a stevedore than a priest; the purple shirt and clerical collar did nothing to belie that impression.

“It was my April Fools’ sermon,” she went on. “I read from the 1631 pressing of the King James in which the printer accidentally left out the word not in a certain commandment. It tells everyone, ‘Thou shalt commit adultery.’ Which was a big hit with the congregation in general.”

I smiled and sat back. “I’ll bet. Although most of the college boys who patronize my little shop don’t really need that kind of encouragement.”

She shrugged. “Small town. What else is there to do?”

“Drink cheap beer, watch high school football, shoot rats at the county dump.” I refilled my cup.

“Those aren’t really acceptable substitutes for sex, though, are they?” She sipped.

My eyebrows arched. “If memory serves.”

She was not in a commiserating mood. “Cry me a river. I’m a priest.”

“You’re an Episcopal priest,” I said. “You’re supposed to have sex. It’s in the Anglican rule book.”

She set her cup down for emphasis. “Let me start over. I’m a female Episcopal priest in a small town in South Georgia. I couldn’t get a date if I had a shotgun and an arrest warrant.”

“Maybe you’re looking for the wrong kind of dates,” I said, “if you think you’re going to need firearms and a legal paper.”

“And besides,” she went on, “you’ve got David. Everybody in town knows you went to dinner with him at that fancy place up in Tifton.”

“Okay, yes, we’ve had a few dinners and some great … conversation.”

“Ah.” She picked up her cup again and drank. “Conversation.”

“Still,” I said with a sigh, “hope springs eternal.”

“What about that tall fireman?” Gloria teased. “The one that put out the fire in your gazebo.”

“Captain Jordon.” I smiled. “He’s called a couple of times. But David is so…”

“The thing you have to know about David is that he moves slowly and carefully,” she said, and her voice was quieter than it had been. “He thinks in terms of growing seasons, not days or weeks. How long did it take for him to build this gazebo? Four months? But just look at it. Look how solid it is, right?”

I stared up at the exquisite ceiling, ornate without being precious, delicate and strong at the same time.

“Maybe that’s the kind of relationship he’s building with you,” she continued, apparently reading my mind.

“Wouldn’t that be nice,” I mused, staring into my coffee.

She looked around the garden. It was something to see. The daffodils were nearly done, but the flowering quince and double-blooming azaleas around the borders of the garden were filled with pink and peach. The phlox carpet around the gazebo was rich purple, and the Johnny-jump-ups were still hanging on. Parsley and sage and tarragon filled the herb garden.

Between the hedge and the back door of the house, I would eventually plant the first of the kitchen garden, the three sisters: squash, corn, and beans. And too many tomato plants, not enough red peppers, and, later, way too much okra.

“I’m thinking of trying tomatillos this year,” I said idly.

“You should do something about the front of the house,” Gloria said instantly. “This looks great back here, but the front of the place looks abandoned.”

She was right. I had neglected the front yard, as had my aunt Rose before me. Her idea was that people wouldn’t take the bookshop seriously if it looked too nice, too Better Homes & Gardens. People would think, she’d told me long ago, that the house was some kind of frou-frou boutique instead of the serious literary institution that it actually was. And I had followed suit. Grass neglected, shrubbery dead, gravel from the driveway spewed everywhere, it did look a little like an abandoned house. Owned by the Addams Family.

The house itself was a proud Victorian remnant of the town’s former glory as a leading producer of turpentine in Georgia. Turpentine money had built the town, and then abandoned it, leaving a few lonely, hulking houses like mine which the town regarded as embarrassing memories of its lost Eden. An Eden that never really existed. I’d managed to get it painted, restored to its former declaration of wealth and taste. But the yard was still a symbol of what had happened to the town after the Depression. Hobo weeds and rock-hard dirt, it was a perennially winter landscape refusing to ever acknowledge that Easter had happened, that spring was abroad in the land.

So I said to Gloria, “You’re right.”

And I stood up so suddenly that it startled her.

“I’m going to that big garden center in Tifton,” I went on.

“Now?”

“No, not now,” I admonished. “What kind of heathen business would be open on Sunday around here?”

“Well,” she assured me, “my place of business was open…”

“Okay.” I ignored her. “I’m going to buy a dozen red azaleas, four flats of impatiens, and some variegated monkey grass. At least.”

She shook her head. “Isn’t that a little pedestrian for a place as unusual as the Old Juniper Bookshop? Don’t you need, like, lupins and climbing jasmine or … wait! Get roses.”

“Well, of course.”

Aunt Rose had actually bred her own hybrid when she’d first retired from New York theatre and moved back to Enigma. She called it “Ophelia’s Last Laugh” and she was uncommonly proud of its unique regal color, which she insisted she’d taken from Gertrude’s speech about Ophelia’s drowning: the long purple of “dead men’s fingers.” But the small-minded American Society of We Get to Reject Your Rose’s Name, or whatever it was called, wouldn’t go for it, so she pulled them all up, cut them all down, and had rosewood footstools made for the various chairs and sofas in the shop. Seemed like an overreaction but Rose was nothing if not theatrical.

Still, a dozen or so Knock Out rosebushes along the front of the porch seemed like the perfect starting place for my new, improved front yard.

“You know you’re going to need a backhoe or something on that ground out there,” Gloria warned me. “Or a pile driver. Maybe a couple of sticks of dynamite.”

“It’s hard,” I agreed, “but smashing into the stubborn clay of my homeland is a perfect way for me to get out my frustrations.”

“What have you got to be frustrated about?” she asked me.

“Did I forget to mention that the only activity between David and me so far is conversation?”

She nodded. “Right. Hang on.”

She took off her clerical collar and unbuttoned the top of her purple shirt.

“What are you doing?” I asked her as she stepped out of the gazebo.

“I’m helping you,” she snapped. “Or did I forget to mention the whole priest-in-a-small-town motif running through my own personal frustration?”

“Got it,” I affirmed. “I’ll get you some gloves.”

Not twenty minutes later we were both out in front of my house, I with my pickax, she wielding a shovel. I’d changed into my cute green overalls and given Gloria an extra-large denim work shirt to wear. She was standing on the footholds of the shovel, balanced perfectly, rocking, trying to coax it into the impenetrable ground. I bashed the pick down over and over again, screaming like a Viking, with no discernible effect. That went on for almost an hour.

“Why are we doing this, again?” Gloria asked, sweating.

“Because it’s spring!” I said, pretending that anger was the same as determination.

She nodded. “Okay. Let’s switch tools.”

I took the shovel and began to skim across the surface of the land, shaving it one thin layer at a time rather than breaking it. After a while I stood back and Gloria smacked down the pick in the same place. The old shave-and-smack method.

Miraculously, or ridiculously, it began to work. Loose rocks and heavy clay gave way, eventually, to something like actual dirt.

Gloria stared down at it. “Now you need some peat moss and some compost. Mix it in with all this crap.”

“Agreed.” I knelt. “Let me just see a little bit more of what’s under the surface. It gets better as you go down, doesn’t it?”

I pulled my big trowel out of my back pocket and began to move things around right next to the front steps. Rocks and dirt and clay went flying.

Then I hit something severely hard a little deeper down. I figured it to be another rock, maybe a larger one. I could see that it was vaguely white and fairly round, and my trowel was no match for it.

I stood and held out my hand. “Shovel, please.”

Gloria handed it over.

I wedged the pointy blade of the shovel between the rock and the loosened ground and leaned in with all my weight. The ground complained and the rock broke.

“Should I use the pickax?” I asked Gloria.

She stood over the spot and stared down. “You seem to be making headway here. I say keep going with the shovel. Try to pry that white rock out.”

I nodded and stood down hard on the shovel with both feet. The ground shifted, the rock moved, the shovel flew away, and I fell backward onto the ground.

Instead of the laughter I expected to hear from Gloria, she gasped—worse than gasped. It was a tearing noise, a warning from a horror film, a sound a priest shouldn’t make.

“Gloria?” I asked, still on the ground.

She stared, wide-eyed. That was her only response.

I got to my feet and went to see what had caused such a garrulous woman to be struck so dumb. And there it was, from Hamlet, act 5, scene 1: Yorick. Not a rock at all.

It was a human skull.

* * *

IT took Billy Sanders exactly eleven minutes to get to the house, and when he did, it was with his siren screaming. He bolted out of the car, face red, eyes wide. He had decided last Christmastime that he was going to run for sheriff, so it was possible that he was trying to impress everyone. But it was more likely that a dead body buried in someone’s front yard was impetus enough. Especially since my house had been the scene of a fairly gruesome murder only six months before.

The fact that I had been Billy’s babysitter when he was eight and I was in high school only made the moment more surreal.

He moved quickly for a boy his size and came to a frozen halt at the front steps, staring down at the treasure Gloria and I had dug up.

“Well.” He sniffed. “That’s a human skull all right.”

Gloria laughed. Partly because it was such an idiotic thing to say, partly because she was a little unhinged by the situation. As was I.

“Who is it?” Billy went on.

“Amelia Earhart,” Gloria said instantly.

“Oh.” Billy looked up, and said softly, with a straight face, “Another mystery solved, then.”

Because, despite appearances, Billy Sanders wasn’t a complete idiot.

Gloria was staring down at the skull. “This had to happen at night.”

Billy looked at her, then at the ground. “Uh-huh.”

“Because,” Gloria went on, “it had to take a while to dig this ground and then to … I mean, wouldn’t someone have noticed?”

“Well, we are at the end of the road,” I said, “and the road mostly has abandoned buildings on it until you get into the center of town. And don’t forget there was a period of time when the shop was closed. Rose was in the hospital and I wasn’t in town yet.”

Billy nodded. “At night, weeknight, shop closed—I believe you’re right. Both of you. Who would have seen this?”

Further banter of that ilk was prevented by the arrival of a pickup truck from Weller’s Funeral Parlor. Two men in denim jumpsuits got out, one with a pick, the other with a shovel, and lumbered over to where the rest of us were standing.

“Shouldn’t we have some kind of crime scene team here?” I ventured.

“Tad and Allie are certified,” Billy said absently. “And the guys from Tifton won’t be here until later this afternoon.”

“Guys from Tifton?” I asked.

“Crime scene investigators,” he snapped. “Like you said. Damn.”

It was the testiest reaction I’d ever heard from Billy. He was clearly more on edge than he looked.

Tad and Allie went to work, starting three feet away from the skull, breaking up the ground in a surprisingly careful, almost gentle way.

“More coffee,” Gloria muttered, and headed into the house.

“Right, sorry,” I agreed. “Billy? You want coffee?”

He blew out his breath. “Yeah.”

I stepped up onto the porch. “You know, Philomena was supposed to come over here for lunch.”

Billy nodded. “I knew she was getting out this weekend. You didn’t go pick her up?”

“She didn’t want me to.”

“Embarrassed,” he assumed.

“She said she didn’t want to bother me,” I told him, headed into the house.

“She’s still not sure you forgive her for … you know.”

Dr. Waldrop, my aunt Rose’s closest friend and life companion, had been so upset that Rose’s will left the bookshop to me that she’d burned down the gazebo behind the house moments after I’d arrived to claim my inheritance. It had taken me a while to forgive her, but I had, eventually, and it was a clue to her weather-beaten personality that she was still worried about my feelings. The incident had also convinced her that she needed to check herself into a care facility, as she had at other difficult moments in her life. And still, she was more concerned with my feelings than anything else. So how could I help loving her?

“I forgave her six months ago.” I sighed. “When I made her an equal partner in this bookshop, I told her I did it because I was keeping it in the family.”

“Because she is family,” he said, following me into the house.

“My point is,” I said, heading for the kitchen, “maybe I should call her and tell her that now’s not a good time for a visit.”

“I understand what you mean,” he said, “but maybe this is just the kind of thing she needs.”

I stopped and turned. “What?”

“This gives her a chance to feel like she’s helping you,” he said softly. “Like she’s comforting you or protecting you. She’s that kind of person; it makes her feel better when she’s helping somebody else. You know?”

I considered what he said. “You’re wasted in the police department. You should be a therapist.”

“Or a priest!” Gloria called from the kitchen.

Billy couldn’t help smiling. “We already got a funny priest in town, and Dr. Waldrop is the best therapist in the state, but I’m not a bad policeman. I like to stay in my own lane.”

“Well, this particular police matter,” I began, glancing toward my front porch, “is going to take quite a bit of police work, don’t you think? I mean, for one thing this is the second dead body we’ve had in this house—just in the past six months. There’s got to be something to that, right?”

“Yeah,” he said, looking around the bookshop. “What is this place, anyway? The kiss of death bookstore?”

“You should change the name to that!” Gloria shouted.

“We already attract enough of the ghoulish crowd as it is,” I said, coming into the kitchen. “Some of the kids at the college refer to this place as ‘the murder shop.’”

Billy sighed. “I love this place. Let’s just keep the Old Juniper Bookshop the way your aunt Rose wanted, hear? This place is a sanctuary, not an attraction.”

“Man, Billy,” I said, catching his eye. “You really have grown up to be a remarkable person. What you just said … it’s a very insightful observation. And subtle.”

And I know this sounds ridiculous, but I could feel that the house agreed. Golden light streamed in through the wavy glass windows. The dust motes, lazy in the sun, moved by some unknown, unseen force, swirled around the bookshelves. Every downstairs room, except the kitchen, was filled with books and records and comfy chairs and antique sofas and for a moment, the briefest of moments, I could hear sentences from every single one of the volumes, like a kind of pale white noise that filled up the entire house. They were written in the alphabet of the air, an alphabet that has only two letters: the sound of all sounds at once—and silence.

2

BILLY AND GLORIA and I were still sitting at the kitchen table in the back of the house when one of the two “certified” front yard diggers came in and stood at the front door, calling out for Billy.

“Officer Sanders?”

“Allie?” Billy was up and out of the kitchen instantly.

Gloria and I followed. Allie’s face was red and wet, and his coveralls were covered in white and red gunk.

“Okay, so, this is weird,” Allie said. “That dirt out there, around them bones? It’s got QUIKRETE mixed in with it. That instant concrete stuff.”

“That’s why it was so hard to get into,” Gloria said, mostly to herself.

“Why would that be?” Billy asked.

“It wouldn’t be no reason to do that,” Allie said. “Not with all the red clay out there too—except to make it really hard to crack open the … you know, the grave, or whatever.”

“That is weird,” Billy agreed.

“Let me get this right,” I said. “You think somebody mixed dry concrete with Georgia clay and buried that body in it?”

Allie nodded. “Yes, ma’am. That’s what it looks like to me.”

“Who would do that?” Gloria muttered.

“Why would you do that?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Allie said. “It don’t make no sense.”

“Except that everybody in town knew how Rose felt about her front yard,” Billy said slowly. “She deliberately wanted to keep it a little spooky. No plants and such, so it wouldn’t be too fancy, or … however you’d say it.”

“Gloria and I were just talking about that,” I said. “She was afraid no one would take the shop seriously if it looked like a tourist attraction.”

Allie grunted a laugh. “Well, it don’t look like that.”

“Anything else?” Billy asked.

“Come on,” Allie said, and he was back outside.

Allie and Tad had made more headway than I might have expected. There was a large oval-shaped space around the bones, about three feet deep, beside a pile of dirt half the size of a Volkswagen. Most of the skeleton was exposed but not entirely unearthed.

“The thing is—” Allie began.

But he was interrupted by Billy’s observation. “That neck’s been broke.”

It only took me a second longer to come to the same conclusion. The neck bones made a right angle and the skull lay flat on the shoulder bone.

“That’s what I mean,” Allie continued.

“Are we thinking that this person was murdered?” Gloria asked, coffee mug in hand.

“Not necessarily,” Billy said.

“Okay, but this person didn’t bury themselves in my front yard,” I assured him. “So somebody—”

“Let’s not jump to any conclusions,” Billy told us all. “We got the coroner and that crew coming from Tifton, and until that happens, I believe we ought not to speculate.”

It was a reasonable, mature suggestion. Which I chose to ignore.

“I see mostly red clay in this pile of dirt, here, Allie,” I observed, “so there couldn’t have been a whole lot of QUIKRETE involved.”

“Well, the clay don’t let the concrete dust get enough moisture to set it right,” Allie explained.

Tad was staring at the pile of dirt.

“But she’s right,” he said without looking at me. “There’s not enough of the stuff to make it as hard as you want concrete to be.”

“It was done hastily,” Gloria pronounced. “Someone was in a hurry to bury the body, not really thinking, maybe panicked, and somehow thought it would keep the body hidden.”

“Could we please stop all this speculation!” Billy demanded, a little louder than he needed to. “It’s more likely to lead a person to a wrong conclusion.”

“Officer Sanders has a point,” Tad agreed. “I mean, for one thing, it’s perfectly legal in Georgia to bury a family member in your yard.”

Allie nodded. “I don’t believe you even need a permit in this county.”

“Well, Rose would never have done anything like that,” I assured everyone. “And all her relatives were dead before she came back to Enigma and started the bookshop.”

“But her family goes a long way back in this house,” Billy said. “This might be some long-lost relative of yours, Maddy.”

It was a testament to Billy’s distracted mind that he did not call me Miss Brimley as he usually did in front of other people, mostly because he thought it made him seem more professional.

We were still standing around outside watching Tad and Allie work when Philomena pulled up in her 1989 Buick LeSabre. It was the only car she had ever owned; she’d bought it new. It still ran perfectly, despite its antique status, for one reason, and that reason was Elbert. He was a genius. I would have stacked him up against any rocket scientist or nuclear physicist on the planet. Except that a world-class car mechanic was infinitely more valuable than any person of science—certainly in Enigma, Georgia. Elbert had taken Igor, my poor old Fiat—so named after a series of unfortunate accidents, none of which were my fault—and made it over in the image of a fire-engine-red angel. The fact that Elbert had done a little time for attempted murder did nothing to diminish my estimation of him.

And there was Philomena, bouncing out of that car like a woman half her age.

“Sugar!” she called out to me, beaming.

We were holding on to each other three seconds later.

I loved Phil. She was a troubled soul, but not without good reason. A bout of rheumatic fever as a child had left her with a panoply of health issues, chronic pain, and occasional doubts about the nature of reality. She had been my aunt Rose’s closest friend for decades, and we treated each other like family. Because I guess that’s what we were.

“I missed you,” I whispered in her ear before letting go of her.

She was dressed in one of her many navy-blue dresses. She wore a silk Hermès scarf around her neck and black horsebit 1953 loafers—a nearly one-thousand-dollar pair of Gucci shoes—on her feet.

“Your visits meant so much to me,” she said, peering past me. “Hey, Gloria. What’s all this?”

Gloria nodded. “Well, Maddy and I were thinking of planting some roses out here and instead we found a skeleton buried in the yard.”

I instantly wished that Gloria hadn’t blurted it out that way.

Philomena blinked once. “What?”

“Maybe you all could go on back inside,” Billy suggested. “Let Tad and Allie work?”

“Hello, Billy,” Phil said absently. “Is there really a skeleton in this yard?”

“Well,” he began.

Phil craned her neck to see into the shallow pit, saw the bones, and immediately closed her eyes.

“Yes,” she managed to say. “Let’s do go inside. I would like to sit down, I think.”

So with that, Gloria and I ushered Phil into the house, through the shop, and landed at the kitchen table. I could have kicked myself for not calling Phil and telling her not to come over. I would have had to explain things, but that clearly would have been better than letting someone in her condition see a skeleton in the yard of her home away from home.

Phil’s life was, by her design, well-ordered. She had a full class load at the college, she kept generous office hours, she graded papers, and she spent most evenings and weekends with me at the bookshop. As she had with Rose when Rose was alive. Deviations from that order were at the very least disconcerting for her. Even the suggestion that someone had been buried in the yard could have, I thought, sent her into a spin.

“Who is it?” she whispered.

I turned on the electric kettle and started preparations for new French press coffee.

“No idea,” I said. “We just discovered it.”

She turned to Gloria, and her voice was hollow sounding. “You were going to plant roses?”

“That was the thought,” Gloria confirmed. “Although mostly Madeline and I were just taking out some very specific frustrations on the dirt. We hadn’t bought any roses yet.”

“You know,” Phil went on, her voice still ghostly, “Rose created her own hybrid. It was never officially sanctioned, but … I have some of them at the college. Or, actually, David has them in his greenhouse. You should plant those.”

I sat down next to her. “Are you okay?”

“Hmm?” She looked into my eyes. “Oh. Yes. But I’ll be better, I think, when I know who was buried in my yard.”

My yard. Well, it was her yard. Half of it, at least.

Gloria broke the partially uncomfortable silence. “So, how was your stay in the looney bin?”

Before I could object, Phil laughed. “Aside from the fluorescent lighting and the medicinal smells, it was very relaxing. My medication was adjusted and I got a chance to really talk it out with my therapist.”

“Talk what out, exactly?” Gloria pressed.

Then I understood what Gloria was trying to do. She wanted to distract Philomena, and maybe me too, from the business in the front yard.

It worked. The three of us spent an hour or more talking about tasteless institutional food, weird therapy jargon, and how full the wisteria in the garden had been that year.

“I thought the clusters of flowers smelled like grapes,” Phil said, “but maybe I was influenced by the fact that they looked like grapes.”

Which was when Billy came into the kitchen.

“Okay,” he announced. “Coroner’s here and says it looks like the victim’s neck was broke, but she can’t tell how long the bones have been in the ground.”

And that provoked another moment of uncomfortable silence.

“It’s a lady coroner?” Phil asked at length.

“What I mean is,” Billy went on, “that your yard is now a crime scene.”

“Are you saying that the lady coroner thinks the pile of bones was murdered?” Gloria asked.

“Suspicious circumstances,” Billy mumbled, “but we’ll all know more once they get everything back to the lab and do the … you know, the tests and … like that.”

Billy was clearly disturbed by the situation.

“So it might not be just a case of some weird but permissible family burial.” I stood up from the table.

Billy exhaled. “Might not be.”

“Okay, so, I hate to sound callous or anything,” I said, “but what does that mean in terms of my opening the shop tomorrow morning?”

He nodded. “They’ll have collected everything they need pretty soon, they said. I don’t see why you couldn’t open as usual, but I’ll ask.”

He turned and was gone.

“You could tell just by looking at it,” Gloria said, “that the neck was broken.”

“Would you like for me to stay here tonight?” Phil ventured. “Maybe you don’t want to be alone.”

Maybe she didn’t want to be alone, I thought.

“I’d love that, Phil,” I told her.

And why not? I wouldn’t like to be alone on my first night home from a stay in a mental hospital. And she had everything she needed in Rose’s room: clothes, toothbrush, pajamas—the memory of Rose, which still hung in the air like a lingering scent.

“Well,” Gloria said, tossing back the last of her coffee and standing, “I’d better get back to the store. I have a baptism at six.”

“The store?” I laughed.

“You know,” Gloria said, headed for the front door, “the Jesus store. You sell books, I sell enlightenment.”

“Not much money in either one, is there?” Phil asked, her attempt at a joke.

“You don’t sell enlightenment,” I objected.

Gloria stopped and turned. “What do you think the collection plate is? I talk about loving your neighbor and you put a fiver in a solid gold dish that costs more than a car.”

“You should talk louder,” Philomena said, staring into her coffee cup.

“What?” Gloria asked.

“Well, somebody didn’t love their neighbor very much,” Phil whispered, “if they broke somebody else’s neck and buried the body in my front yard.”

Gloria did not offer an immediate response.

ALL MY BONES. Copyright © 2025 by P. J. Nelson. All rights reserved. For information, address St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...