Emily stepped up to her patient’s bed. She’d read his chart before entering the cubicle, added the data to what her paramedic brother and his partner had scribbled in their report: low blood pressure, low-grade fever, low blood sugar, shallow breaths . . . She’d order a full workup, starting with X-rays to rule out a concussion. Based solely on the pallor of his skin, she’d order extensive bloodwork, too.

Grasping the boy’s thin wrist, she smiled. “My name is Dr. White. What’s yours?”

“Gabriel Baker. But you can call me Gabe.”

“Gabe. Simple and strong. I like it.” Silently she concentrated on her watch face: seventy pulse beats instead of the normal eighty to one hundred twenty.

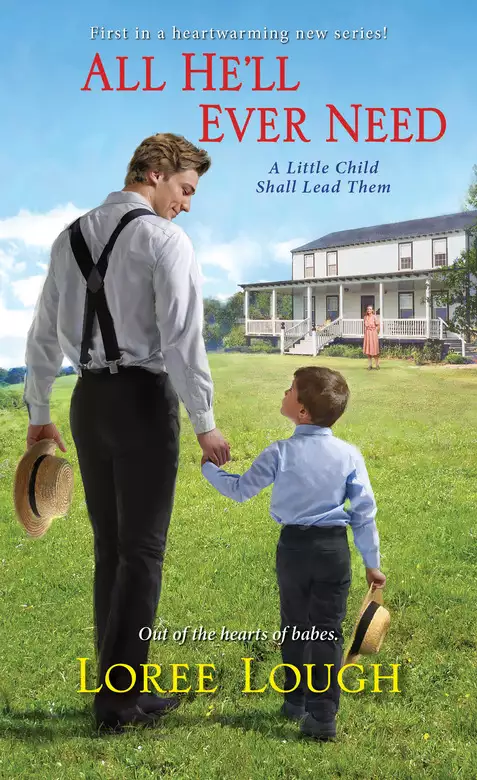

“I’m his father. Phillip Baker.”

How she’d overlooked him, Emily couldn’t say. He stood no less than six foot two and likely weighed in at two hundred pounds of raw, broad-shouldered muscle.

“I’ll need your permission to run some tests on little Gabe here.”

“Of course. Anything. Whatever you need. Whatever he needs.”

He’d tried to mask it, but she heard the unease in his voice, noted the “deer in the headlights” glint in his eyes— gray-blue eyes that reminded her of a pre-storm sky. His obvious distress surprised her, because Amish males were, in her experience, stoical.

Emily softened her tone. “If either of you have questions, please feel free to ask them, and I’ll explain everything in words Gabe can understand. And whenever possible, you’re welcome to stay with him.”

“Good, good.”

She looked past the boy’s small, inactive body, where her brother stood, pecking the small keyboard of his tablet. “Where’s Al?”

White looked up from the device. “He had to leave.” Grinning, then rolling his eyes, he added, “Didn’t want to be late for Sheila’s birthday party.”

Over the years, she’d heard many stories about his partner’s demanding wife.

“Can’t say I blame him,” White admitted.

“And you stayed behind because . . . ?”

“Because I promised this li’l dude I’d stick around while the intake lady grills his dad.”

How like Pete to make such an offer. She’d never admit it aloud, but he’d always been her favorite sibling. When Miranda blamed Emily for breaking their mother’s crystal bud vase, Pete stepped up and confessed to a crime he hadn’t committed. And on that terrifying, stormy night when Joe thought it would be funny to lock her in the basement? It had been Pete who’d climbed through a veil of spiderwebs covering the ground-level window to set her free. When his first love dumped him for the school’s quarterback, it had been Emily he’d turned to for comfort. Quirky and daring, Pete often terrified her with risky antics, like diving from one of the tallest trees on the banks of Lake Kittamaqundi, to firing off kit-made rockets, swallowing live goldfish, and eating thumb-sized beetles.

“I’m not surprised that you stayed.”

Pete’s cheeks reddened a bit. “Yeah, well,” he said around a playful grin. “What’re you still doin’ here? I thought this was your weekend off.”

Emily had volunteered to stand in for Dr. Cartwright, who’d volunteered to chaperone his son’s camping trip. To admit it would start a flurry of questions: What had Cartwright promised in return? When would she get some downtime? How many patient charts—hers and Cartwright’s—was she juggling? Truth was, she’d rather deal with a crazy-busy schedule than go home alone to think about her dismal social life.

“Weekend off?” She forced a laugh. “What’s that?”

He walked around to her side of the bed and gave her a sideways hug. “What was it ol’ Abe Lincoln said about fooling people?”

Emily, who’d minored in history, didn’t bother pointing out that no written evidence existed to prove exactly what the sixteenth president had said, or if he’d said it at all.

“Call me when you finally decide to leave this disinfectant-scented place. I’ll buy ya a pizza at Tominetti’s.”

Standing on tiptoe, she kissed his cheek. “Sounds good.”

“Promise?”

“Promise.”

On his way into the hall, he extended his hand to Mr. Baker. “Good luck. That’s some great kid you’ve got there.”

“Yes. Yes, he is. And thanks for staying with him.”

The instant Pete turned the corner, Emily unpocketed her stethoscope and leaned closer to the Amishman’s son. Slow, irregular heartbeats concerned her, especially in one so young.

“Let’s sit you up,” she said with a confidence she didn’t feel, “so I can listen to your lungs.”

It took every bit of the child’s strength to comply. His father must have noticed, too, for he moved closer to help support the boy’s narrow back.

“Nice deep breath in, okay?”

Gabe inhaled and exhaled another half dozen times. Satisfied that she didn’t hear the typical crackle or wheeze that signaled pneumonia, Emily helped him ease back onto the pillows and pressed the diaphragm to his chest once again, hoping something had changed since the last check.

It had not.

“What’s wrong?” Mr. Baker asked.

Gabe fixed his big-eyed gaze on her face, waiting for her reply.

“We don’t know that anything is wrong,” she said, choosing her words carefully. “I’ll have more answers for you once the test results come in.”

His quick nod told her that he got it: She didn’t want to speculate and risk frightening his son.

She repocketed her stethoscope and parted the partition curtain. “I’ll be back just as soon as I’ve ordered those tests.”

A furrow formed between the man’s well-arched eyebrows, a sure indicator that a hundred questions churned in his mind. She didn’t know why, but it was difficult to leave him—and his little boy—on their own.

“Is your wife on her way to the hospital?”

“We, ah, Gabe and I, we lost her some years back.”

If this wasn’t one of those “wish the floor would swallow me” moments, she didn’t know what was. “Oh. I’m sorry. So sorry to hear that.” She couldn’t imagine going through something this traumatic alone.

She motioned for him to join her in the hall. And when he hesitated, she said, “Just a few questions, and we’ll leave the curtain open, so you can keep an eye on him.”

Even with that assurance, Baker seemed uncertain. But he followed and stood facing her, arms crossed over that broad chest, feet shoulder-width apart.

“How often does Gabriel experience these bouts of dizziness?”

He shook his head. “He isn’t one to complain, so I honestly don’t know.”

No surprise there, either. In her experience, Amish parents didn’t like admitting that something regarding their spouses, parents, or children had slipped their notice.

Baker’s gray-blue eyes narrowed. He licked his lips. Clamped his teeth together so tightly that it caused his jaw muscles to bulge. It couldn’t be easy, raising a small boy all by himself. When he’d greeted her earlier, she’d felt thick calluses on his palm, proof that he worked long, hard hours providing for his son.

“Is Gabe your only child?”

“Yes.”

Ah, she thought, a man of few words. At times like these, Emily didn’t know whether to classify the trait as good or bad. She felt sorry for him. But sympathy wasn’t doing Gabriel any good. Wasn’t doing his nervous father any good, either.

“I’ll send in a nurse to take some blood. As I said, we’ll have a better idea what’s causing his problems once the lab reports come in.” She’d let him wrap his mind around that before letting him know there would be other tests: EKG, EEG, X-rays, scans . . .

“How much . . .” He swallowed. “How much time will all of that take?”

Emily got the feeling his latest concern, spawned by her list, was what it would all cost. That answer would have to wait. Typically, although the tests could be completed in a few hours, it might take days to get the results. Longer, if the lab was backed up. From what she’d seen so far, this patient couldn’t wait days. “I’ll call in a few favors to speed things up,” she said, as much to herself as to Baker.

He drove a hand through thick sandy-blond waves. “All right. Thank you.”

Emily waited until he returned to his son’s side. She barely knew him, so why did it hurt to watch his shoulders slump under this extra burden? Good thing there are rules about doctors fraternizing with patients and family members because . . .

Forcing the very idea from her mind, she made her way toward the nurses’ station. After typing up the orders for a full blood workup, she wheeled the desk chair away from the computer. “Hey, Jody, this little boy—Gabriel Baker—is Amish. Four years old. No experience with needles, and you’re so good with blood draws. . . .”

“Say no more,” the nurse said. “I’ll give him plenty of extra TLC.” She leaned in close and whispered, “Are the parents hoverers?”

“The mom died a few years ago.” She remembered the way Baker had looked and sounded when he’d shared that bit of information. If she had to guess, Emily would say he loved his wife, still. “Mr. Baker is concerned, understandably, but seems reasonable.”

“In general? Or for an Amish guy?”

“Both, I guess.”

“Good. Because—and I don’t mean to complain, or demean them in any way—but those people can be tough to work with.”

Emily understood. Perfectly. Facing the computer again, she typed in a request to put a rush on Gabriel’s tests and labs, remembering that her last Amish patient had been the middle-aged mother of three small boys. The woman refused to explain why she’d ingested nearly a whole bar of caustic lye soap, until Emily sent her husband to the cafeteria. He wasn’t out of earshot a minute when the woman’s confession spilled out: Upon learning she didn’t want any more children, he’d started abusing her. Marital relations, he’d insisted, were part of her wifely duties, whether or not they resulted in a child. Since the Amish didn’t believe in oral contraceptives or medical procedures and devices to prevent pregnancy, Emily had suggested natural methods, such as tracking her menstrual cycle. The very idea had put the woman on the verge of hysteria. When the last doctor had recommended that course of action, she’d told Emily, her husband refused to cooperate with even those short periods of abstinence. Now, as he returned carrying only one Styrofoam cup of coffee, the wife withdrew again, trembling and avoiding his eyes. Emily knew that the husband’s behavior was the exception, not the rule in the community. She’d taken an oath to respect her patients’ wishes, especially those stemming from religious beliefs. But she hadn’t promised to overlook assault. While a nurse pumped the wife’s stomach, Emily backed the husband against a wall and made it clear that the contusions and abrasions she’d found during the initial exam were clear evidence of spousal abuse. Abuse, she’d stressed, that, if reported, would result in arrest and jail time. Abuse that, by law, she was required to report. Nothing could have pleased her more than the terror flickering in his eyes. She hadn’t seen the couple since, hopefully because her threat had been enough to put a stop to the beatings.

Based solely on Baker’s interactions with Gabriel and the gloom that had shrouded him when speaking of his wife’s passing, Emily concluded that he had never raised an angry hand against Gabe or his mother. Yes, his “only the facts” responses had been borderline gruff, but the fear of losing his little boy likely explained his reticence. That, and worries about how he’d pay for it all.

Fingers curved over the computer’s keyboard, she typed “Amish” into the Religion space. Treating this child would no doubt be a challenge, compounded by the Amish old-world view of medicine and female practitioners.

She hit Enter to save the file. Hit it harder than intended, drawing the attention of two nurses in the station.

Diagnosed with dyslexia during junior high, Emily had faced numerous challenges in college and med school. Her family—everyone but Pete, that is—had tried to talk her into choosing an easier career path. She’d proven all of them wrong, outpacing and outproducing many of her male classmates, and graduating at the top of her class at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

She would prove herself to Mr. Phillip Baker, too.

Don’t be so self-centered, she chided herself. You’ll do it for the little boy’s sake, not to gain his father’s approval!

Still, it would be satisfying, once she’d diagnosed and treated Gabriel, to see relief and approval in his father’s eyes.

His big, long-lashed, blue-gray eyes . . .

It was barely dawn when another call put Pete back in the ER.

“Where’s Emily?”

“Seeing other patients, I expect,” Phillip said.

“How’s Gabe?”

“To quote your sister, we won’t know anything until the test results come back.”

“Well, good that he fell asleep. Place like this? You grab a few z’s whenever you can.”

It was good, seeing that Gabe had dozed off.

“He’s in good hands,” Pete said, “so if you want me to drive you back to the hardware store to get your truck . . .”

Phillip almost declined. But he had much to do at home. His only dilemma, whether or not to wake Gabe to let him know he’d be back, soon.

As if the EMT had mind-reading talents, he said, “No need to wake the poor kid. The nurses will explain where you are, and that you won’t be away long.”

It made sense. “Thank you, Mr. White.”

Pete held up a hand. “Hey. Mr. White is my dad’s name.” Extending the hand to grasp Phillip’s, he said, “It’s Pete.”

While walking toward Pete’s vehicle, Phillip began compiling a short list of things he’d need to do upon arriving at home: update his family about Gabe’s condition; check his answering machine messages and make some calls to customers, explaining why it might take a while to finish repairing the motors still in his shop. It was good, knowing he’d hear only supportive responses.

The men rode in silence for several minutes, Phillip trying his best to see the beauty in the red-gold sunlight shimmering on the clouds. His wife had painted similar vistas, some on cloth squares that his mother added to quilts, some on old milk cans, and half a dozen or more on scrap wood. What a struggle it had been for her to pretend she wasn’t proud of her God-given talent! He shook his head to clear the memory.

“You can quit worrying. I wasn’t kidding when I said that Emily is the best.”

Pete had mistaken Phillip’s silence for concern about his sister’s abilities, which, in Phillip’s opinion, still remained to be seen. “That’s good to hear.”

“Can I ask you a question, Phil?”

“I can’t promise to answer, but you’re free to ask.”

“All the other Amish I’ve met speak with some kind of German accent or something. . . .”

“Pennsylvania Dutch.”

“Yeah, that. They rarely use contractions. The men wear suspenders, not leather belts. Beards. Straw hats. You don’t do any of that. So what’s the story? You only part Amish or something?”

At fourteen, he’d had a long talk with the bishop, and after explaining what he hoped to do for a living, Fisher gave him permission to look for work in town. As it turned out, none of the auto mechanics in Oakland were hiring, but a local contractor was, and he’d joined the crew within minutes of filling out his employment application.

“I worked for a home builder as a teen. Found it was easier to imitate the other men’s speech and clothing than defend mine.” Not many in the community had made the same decisions, and those who still abided by the old ways made no secret of their disapproval. There were enough, though, who seemed to share his opinion . . . that as long as he stayed right with the Almighty, the others’ opinions shouldn’t matter.

“Kids can be mean,” Pete said. “And adults can be meaner. They’ve had more time to practice.”

He remembered well how, during that first meeting with Buzz Myers, the boss had challenged Phillip by asking him to identify every instrument stored in the shoulder-height toolbox, lying on the long workbench beside it, and hanging from the pegboards above it. Phillip had passed the test, despite having to guess at the names of several power tools. By week’s end, his coworkers—most old enough to be his father—approved of his work ethic to the point that they’d willingly shared tricks of the trade that had taken them years to hone.

“Then we’re not that different, after all,” Pete said. “I spent a couple summers working for a Baltimore home builder.” He laughed. “Learned some colorful language from those guys, let me tell you! Learned still more during my years as an Army medic. Between the two, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. Driving ambos pays the bills, and I build stuff in my spare time.”

Funny, Phillip thought, that his positive experience with Myers hadn’t changed his desire to work with motors. If anything, the job had only underscored his desire to fix broken things.

Pete navigated his boxy SUV into the parking space beside Phillip’s pickup.

“How many miles have you racked up on that old beast?”

“She just turned over 155,000. Still runs like new, though.”

“Man.” Pete whistled. “Amazing.” He patted the steering wheel. “This thing is only a year old. Not even twelve thousand miles on her, and she’s been in the shop twice.” He shook his head. “Who does your tune-ups?”

Phillip opened the passenger door. “That’d be me. It’s how I earn a living.”

Extending his right hand, Pete grinned. “I might just be in touch when my warranty runs out.”

“I’ll appreciate the business. And thanks for the lift,” he said, stepping onto the blacktop. “Thanks for everything you did for my boy, too.”

“Hey. All part of the job.”

Phillip wasn’t buying it but kept it to himself.

“Happy to be of service. He’s a great kid. If I ever have a son, I’ll consider myself blessed if he’s anything like Gabe.”

“Thanks.” It seemed dishonest to take any credit for Gabe’s temperament. Everything good about that boy came by way of his mother.

“One last thing, Phil . . . I know you people aren’t in favor of women in positions of authority, but you can bet on this: My sister’s the best. She’ll take good care of Gabe. I’d stake my life on it.”

“We don’t have problems with women in positions of authority. Provided, of course, the women in question have their priorities straight.”

“In other words . . . husband, kids, house first, then job-related duties?”

“Close.” Phillip smiled. “God goes at the top of the list.” He thanked Pete again and closed the passenger door. He couldn’t wait to get back to the house he’d built, board by board and brick by brick, as a wedding gift for Rebecca. Couldn’t wait to eat a decent meal, shower and change into fresh clothes, update his family and customers, and head back to the hospital. The image of Gabe, all alone in that room, looking small and vulnerable and afraid, would shadow him until he returned.

His mother must have heard the truck’s tires grinding over the gravel drive as he pulled in beside the house. The instant his feet hit the ground, she enfolded him in a crushing hug.

“Oh, thank the good Lord!” Sarah said. “I have been frantic since Micah told me what happened in town.”

Word traveled fast in a community the size of Pleasant Valley. The clerk must have made a few calls, and considering the human tendency to dramatize things, no telling how much she’d embellished the story. He shuddered to think how much it might have changed by the time word reached his mother.

She’d probably been up all night, praying and pacing, doing her best to press worry to the back of her mind while. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved